|

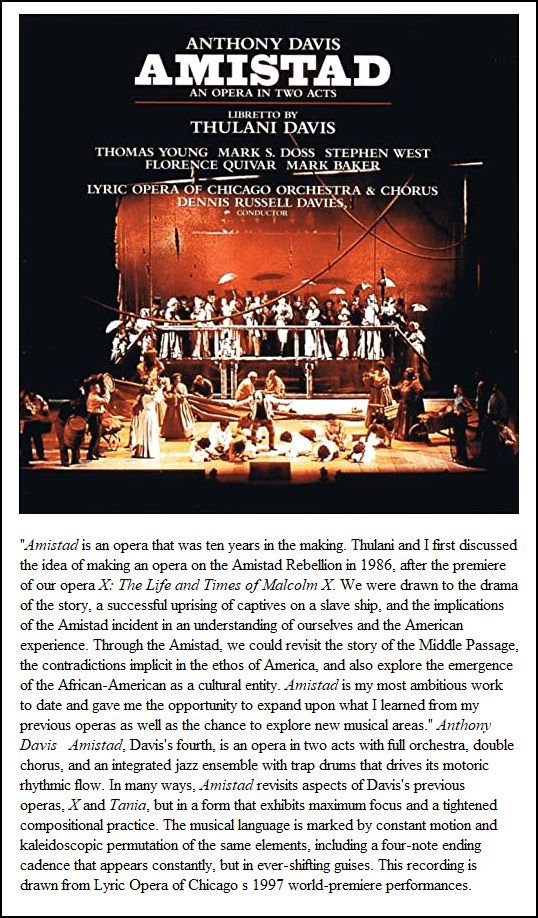

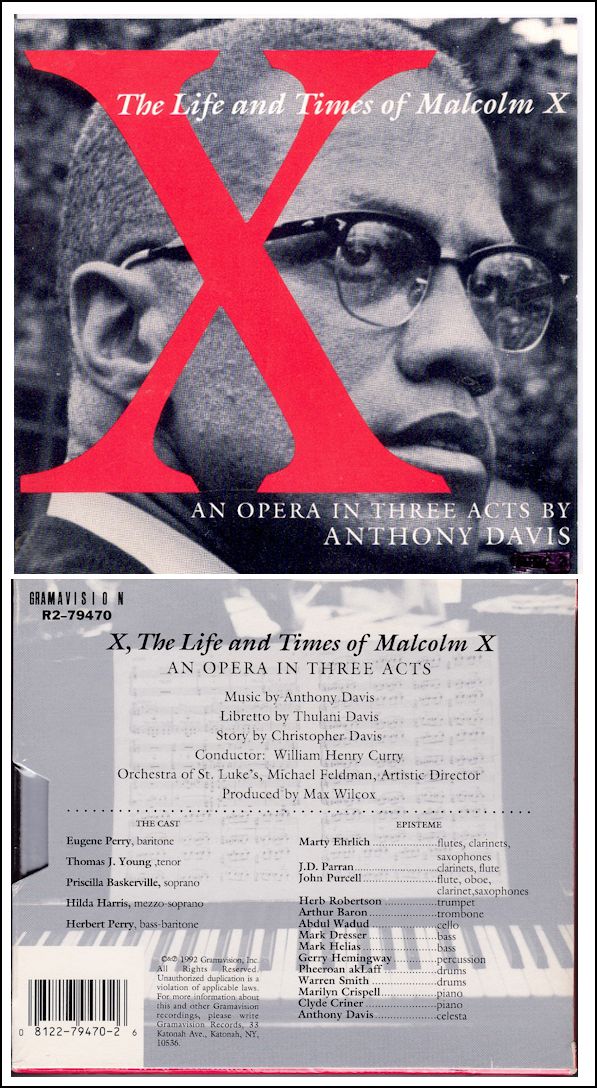

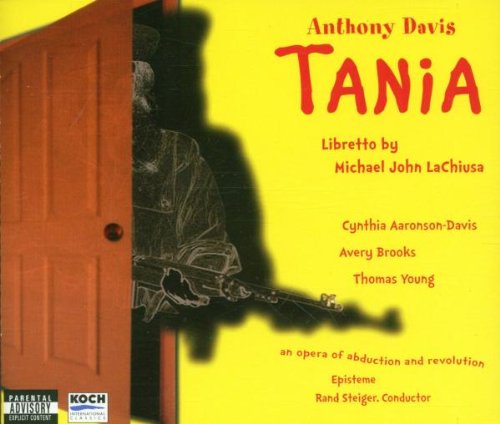

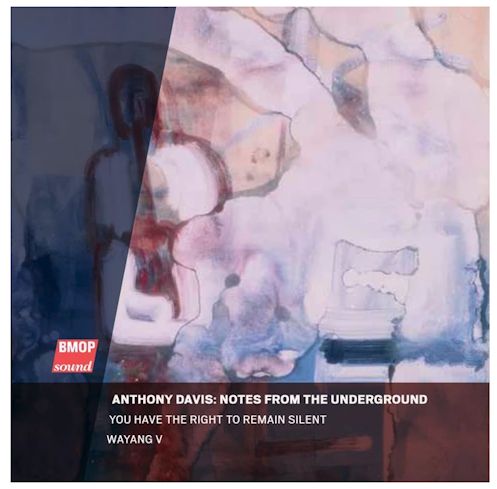

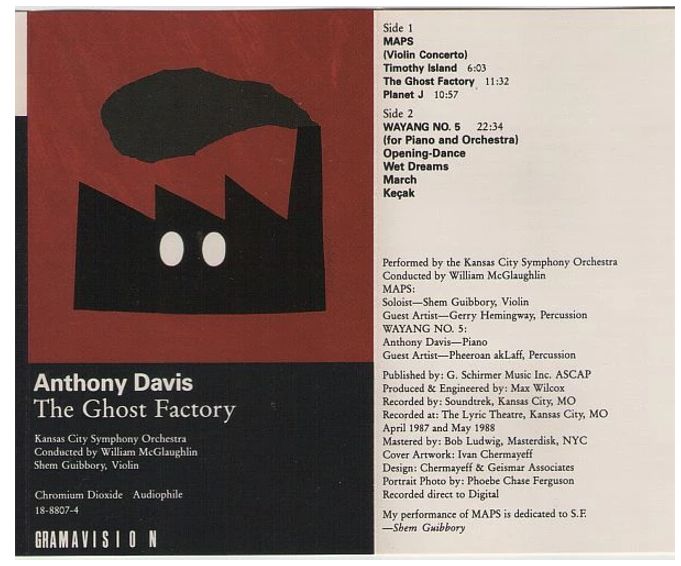

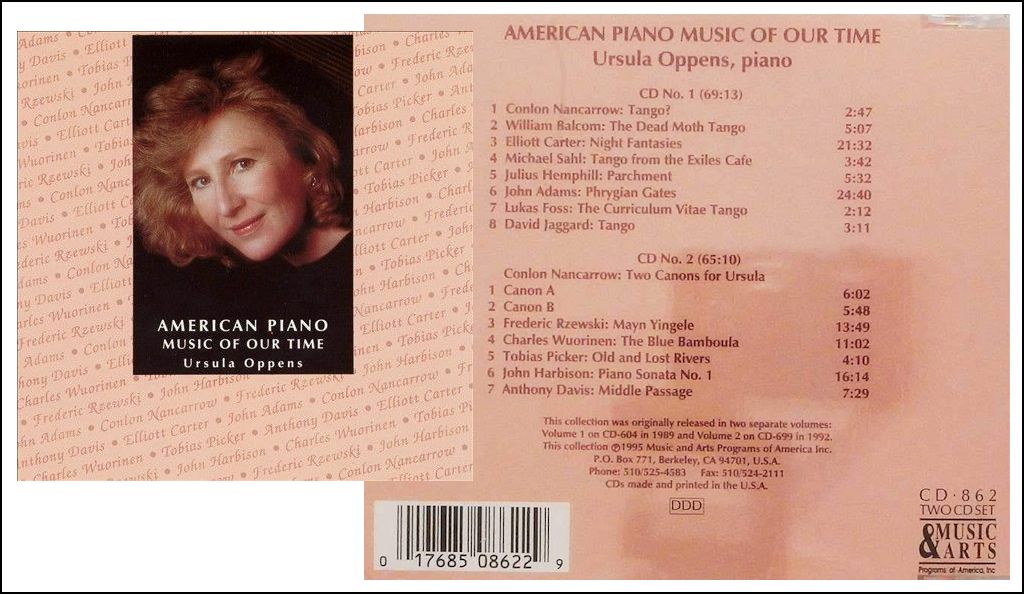

Anthony Davis (born February 20, 1951) is an internationally known composer of operatic, symphonic, choral, and chamber works. He is also known for his virtuoso performances both as a solo pianist and as the leader of the ensemble Episteme, a unique ensemble of musicians who are disciplined interpreters as well as provocative improvisers. In April 1993, Davis made his Broadway debut, composing the music for Tony Kushner’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Angels in America: Millennium Approaches, directed by George C. Wolfe. His music is also heard in Kushner’s companion piece, Perestroika, which opened on Broadway in November 1993. He joined ALT's faculty as a guest mentor in the winter of 2008. As a composer, Davis is best known for his operas. X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X, which played to sold-out houses at its premiere at the New York City Opera in 1986, was the first of a new American genre: opera on a contemporary political subject. The recording of X was released on the Gramavision label in August 1992 and received a Grammy Nomination for "Best Contemporary Classical Composition" in February 1993. "[X] has brought new life to America's conservative operatic scene," enthused Andrew Porter in The New Yorker. "It is not just a stirring and well fashioned opera -- that already is much -- but one whose music adds a new, individual voice to those previously heard in our opera houses." Davis's second opera, Under the Double Moon, a science fiction opera with an original libretto by Deborah Atherton, premiered at the Opera Theatre of St. Louis in June 1989. His third opera, Tania, with a libretto by Michael-John LaChiusa and based on the abduction of Patricia Hearst, premiered at the American Music Theater Festival in June 1992. A recording of Tania was released in 2001 on Koch, and in November 2003, Musikwerkstaat Wien presented its European premiere. A fourth opera, Amistad, about a shipboard uprising by slaves and their subsequent trial, premiered at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in November 1997. Set to a libretto by poet Thulani Davis, the librettist of X, Amistad was staged by George C. Wolfe. His most recent opera, The Central Park Five, received its critically acclaimed premiere at Long Beach Opera in 2019. The work won the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 2020. Reacting to two of Davis's orchestral works, Maps (Violin Concerto) and Notes from the Underground, Michael Walsh said in Time Magazine: "Imagine Ellington's lush, massed sonorities propelled by Bartók's vigorous whiplash rhythms and overlaid with the seductive percussive haze of the Balinese gamelan orchestra, and you will have an idea of what both the Concerto and Notes from the Underground sound like." Davis's works also include the Violin Sonata, commissioned by Carnegie Hall for its Centennial; Jacob's Ladder, a tribute to Davis's mentor Jacob Druckman commissioned by the Kansas City Symphony; Esu Variations, a concert opener for the Atlanta Symphony; Happy Valley Blues, a work for the String Trio of New York with Davis on piano; and "Pale Grass and Blue, Then Red," a dance work choreographed by Ralph Lemon for the Limon Dance Company. His orchestral works have been performed by the New York Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, Atlanta Symphony, Orchestra of St. Luke's, Brooklyn Philharmonic, Kansas City Symphony, Beethoven Halle Orchestra of Bonn, and the American Composers Orchestra. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed Davis's opera X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X in concert in November 1992 as part of the Chicago Humanities Festival. The Pittsburgh Symphony commissioned a concert-opener from Davis entitled Tales (Tails) of the Signifying Monkey. In the 2003-2004 season Davis served as Artistic Advisor of the American Composers Orchestra's Improvise! festival and conference which featured a performance of Wayang V with Davis as piano soloist. Oakland Opera Theatre presented X, The Life and Times of Malcolm X in 2006, and Spoleto Festival USA produced Amistad in its revised and reduced form in 2008. The La Jolla Sympony premiered Amistad Symphony in 2009. Born in Paterson, New Jersey, on 20 February 1951,

Davis studied at Wesleyan and Yale universities. He was Yale's first

Lustman Fellow, teaching composition and Afro-American studies. In 1987

Davis was appointed Senior Fellow with the Society for the Humanities

at Cornell University, and in 1990 he returned to Yale University as Visiting

Professor of Music. He became Professor of Music in Afro-American Studies

at Harvard University in the fall of 1992, and assumed a full-time professorship

at the University of California at San Diego in January 1998. Recordings

of Davis's music may be heard on the Rykodisc (Gramavision), Koch and Music

and Arts labels. His music is published by G. Schirmer, Inc.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

In July of 1992, Anthony Davis was in Chicago for a concert performance

of X at the Third Annual Chicago Humanities Festival. He agreed

to sit down with me for a half hour, to talk about his work and ideas. Portions

of our discussion were broadcast a couple of times on WNIB, Classical 97

in Chicago, and now the entire conversation has been transcribed and presented

on this webpage.

In July of 1992, Anthony Davis was in Chicago for a concert performance

of X at the Third Annual Chicago Humanities Festival. He agreed

to sit down with me for a half hour, to talk about his work and ideas. Portions

of our discussion were broadcast a couple of times on WNIB, Classical 97

in Chicago, and now the entire conversation has been transcribed and presented

on this webpage. BD: We were talking about the voice a little bit ago.

Are you very careful to make sure that the voice is not covered by a

large orchestra, or by loud orchestration?

BD: We were talking about the voice a little bit ago.

Are you very careful to make sure that the voice is not covered by a

large orchestra, or by loud orchestration?

Davis: Not necessarily. I doubt that was true.

Some might be interested, but I find that there’s a special audience

for new things, and there are people who want to hear the new works and

hear the things that are on the edge. They want things that challenge

them in that way, and they also want to hear what’s going on in American

forms, no matter how you define an American form. They might

not be interested in hearing a European form or European music, and that’s

all right. There are people who like to hear European music who don’t

want to hear American things, and that’s all right too. I find myself

very interested. I’ve gone to a lot of operas in the last few years

to hear new things, and I had to catch up and hear Traviata and

Bohème for the first time. That was very important to

me, and was part of my musical development.

Davis: Not necessarily. I doubt that was true.

Some might be interested, but I find that there’s a special audience

for new things, and there are people who want to hear the new works and

hear the things that are on the edge. They want things that challenge

them in that way, and they also want to hear what’s going on in American

forms, no matter how you define an American form. They might

not be interested in hearing a European form or European music, and that’s

all right. There are people who like to hear European music who don’t

want to hear American things, and that’s all right too. I find myself

very interested. I’ve gone to a lot of operas in the last few years

to hear new things, and I had to catch up and hear Traviata and

Bohème for the first time. That was very important to

me, and was part of my musical development.

Shem Guibbory - ViolinistInternationally acclaimed violinist Shem Guibbory, an award winning soloist and chamber musician, has created an important mark on the face of today’s music world as a talented performer, an artistic producer, and a successful entrepreneur. Long hailed for his interpretations of 20th Century music, his recording of Violin Phase by Steve Reich on the ECM label has become an American classic of avant-garde music.

“By nature and by choice, I look for the commonality in all things musical and artistic in our culture and all cultures,” he says. “Those things that tie us together as human beings are part of the driving force in my creative process. I believe that Art has a potency that is as just as relevant to today’s societies as ever before.” Throughout his career, Mr. Guibbory has sought out and found imaginative ways to use new and old music to bring mutual understanding to the global community. With co-creator and director Margaret Booker and writer Robert Schenkkan, he created the musical fable A Night at the Alhambra Café (2002-2008). Mr. Guibbory’s current work includes the music programs Journey of 100, Evolution of a 21st Century Violinist, and Memories and Reflections (Enesco and Laytin). He is also developing a new performance work featuring Russian/American artist Grisha Bruskin and Irish/American painter Timothy Hawkesworth entitled Accidental Heroes. His latest CD, Voice of the People (2010), received excellent reviews;. It combines Gabriela Lena Frank’s Peruvian-influenced music with Dimitri Shostokovich’s Sonata For Violin And Piano, Op.137 (1968), and “it illustrates people’s attempt to find their own slice of humanity within the chaos of life…I believe that when we communicate with people through their arts, it’s far easier to understand them.” Since 1992, Mr. Guibbory has been a member of the first violin section of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, and has appeared as soloist with the New York Philharmonic, the Beethoven Halle Orchestra, the Kansas City Symphony and the Symphony of the New World. He was the original violinist in the Steve Reich Ensemble and has performed recitals and chamber music throughout the U.S., Canada, and Europe. He has also recorded five CDs with Anthony Davis, including Maps, a violin concerto commissioned by the Kansas City Symphony, and released on Gramavision. Mr. Guibbory has received fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation (Bellagio), the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and Spain’s Centre por Ars y Natura. He has been a faculty member of the Bennington Chamber Music Conference for over three decades, during which time he served as Music Director for nine consecutive years. As Music Director he has twice been honored with the ASCAP/CMA Award for Adventurous Programming. Close associates have included such extraordinary composers as Steve Reich, Ornette Coleman, Muhal Richard Abrams, Douglas Cuomo, Jeffrey Levine, Earl Howard, and Anthony Davis. He has premiered over 60 new compositions, of which 30 were written expressly for him. Additionally, he has collaborated with numerous dance companies, has served as co- director of NovEnsemble with choreographer Joan Lombardi, and toured with Belgian choreographer Anne-Theresa de Keersmaker. He was one of the lead artistic producers of West Goes East, a 30-year retrospective of CalArts alumni performances, which sold out its four New York City performances. A graduate of the California Institute of the Arts, he has served as co-chair of the Special Projects Committee of the CalArts Alumni Association (2005-2009) and beginning in 2011 serves on the Board of Directors of the Recording Musicians’ Association, NY Chapter. Mr. Guibbory made his recital debut at New York City’s Alice Tully Hall in 1988. His recordings can be found on the ECM, Gramavision, Opus 1, DG, Albany, Bridge, MSR Classics and CRI labels. His principal Violin teachers were Broadus Erle, Romuald Tecco, Evelyn Read and Sophie Feuermann. |

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 17, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB about four months later, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.