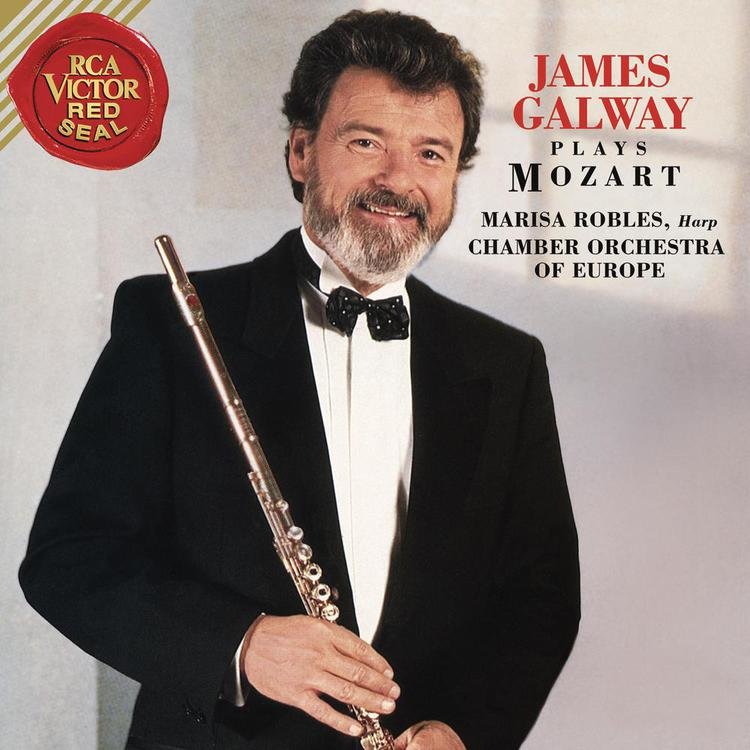

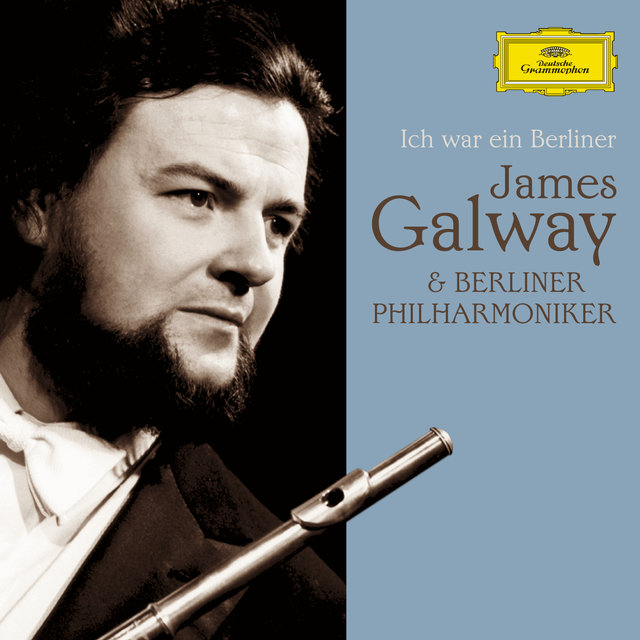

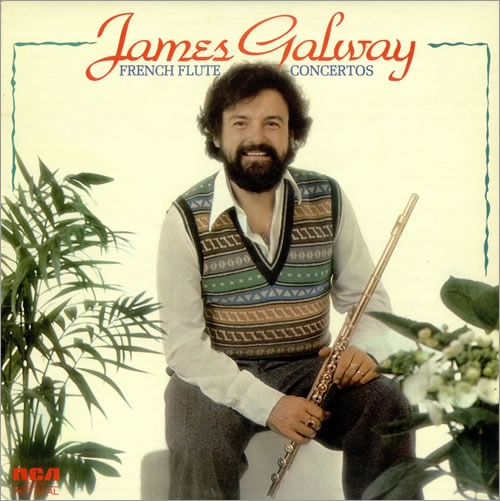

Sir James Galway is internationally regarded as both a matchless

interpreter of the classical repertoire and a consummate entertainer.

With his unique sound, superb musicianship and dazzling virtuosity,

he has a charismatic appeal that crosses all musical boundaries and

has made him one of the most respected and sought-after performing artists

of our time. He also devotes much of his free time to his duties as

President of Flutewise, a non-profit organization that donates instruments

to low-income students and young people with disabilities.

Sir James Galway is internationally regarded as both a matchless

interpreter of the classical repertoire and a consummate entertainer.

With his unique sound, superb musicianship and dazzling virtuosity,

he has a charismatic appeal that crosses all musical boundaries and

has made him one of the most respected and sought-after performing artists

of our time. He also devotes much of his free time to his duties as

President of Flutewise, a non-profit organization that donates instruments

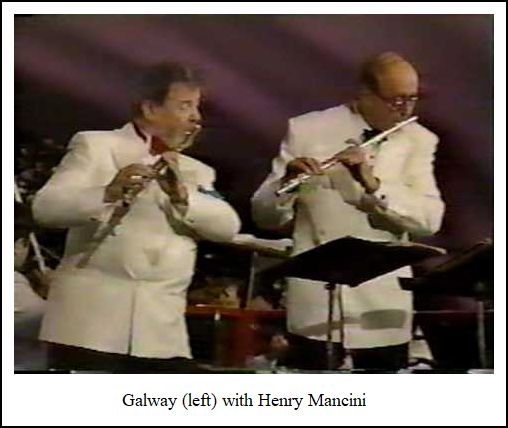

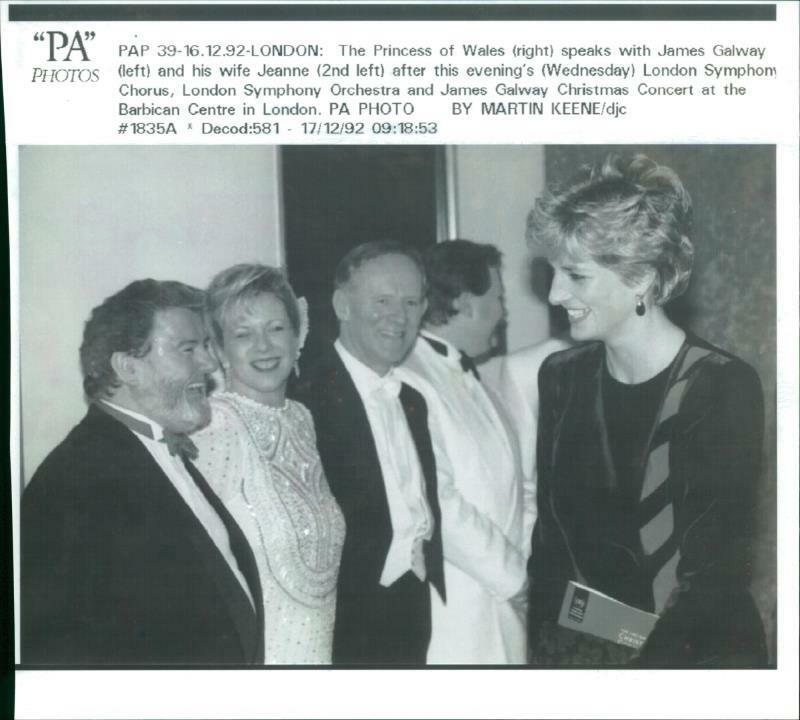

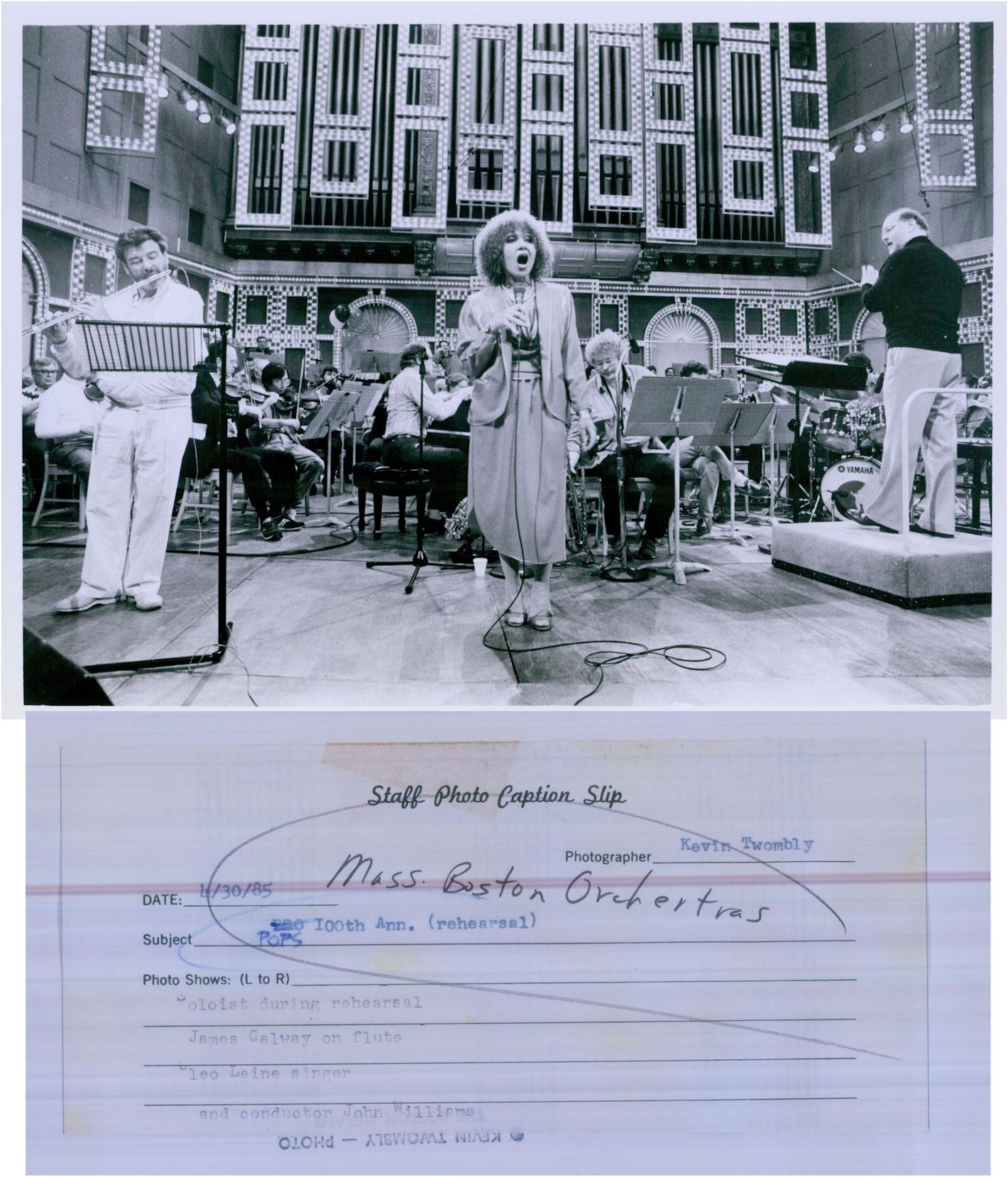

to low-income students and young people with disabilities.Born in Belfast December 8, 1939, Sir James played the penny whistle as a small child before switching to the flute. He won a scholarship to the Royal College of Music in London and continued his studies at the Guildhall School of Music and later the Paris Conservatoire. Sir James began his career at the Sadler’s Wells Opera Company and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden which led to positions with the BBC Symphony Orchestra where he played piccolo. He was then appointed principal flautist of the London Symphony Orchestra and subsequently of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1969, Sir James Galway was appointed principal flute of the Berlin Philharmonic. In 1975 Sir James launched his career as a soloist and, with the help of best-selling discs and frequent television appearances, quickly became a household name. Since then he has travelled extensively, giving recitals, performing with the world’s leading orchestras, participating in chamber-music engagements, popular music concerts and giving master classes. In 1990 he took part in the historic “The Wall” concert in Berlin and in 1998 he was the only classical musician to participate in the Nobel Peace Concert in Oslo. He is also a frequent guest on television programmes in the USA. On 4 July 2000 he helped celebrate the first Independence Day of the century as a guest soloist with the National Symphony Orchestra in a nationally televised PBS special entitled “A Capitol Fourth”, broadcast live from the West Lawn of the Capitol. Sir James has also taken up the baton and in addition to numerous conducting engagements around the world he is Principal Guest Conductor of the London Mozart Players. In 1978 Sir James Galway was awarded the Order of the British Empire, and in June 2001 he received the honour of knighthood from Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II [shown in photo]. In 1997 he was named “Musician of the Year” by Musical America and has received Record of the Year awards from Billboard and Cash Box, as well as the Grand Prix du Disque for his recordings of Mozart’s Flute Concertos and numerous gold and platinum discs. In 2004 he received the President’s Merit Award from the Recording Academy at the Grammy’s 8th annual “Salute to Classical Music and in 2005 he was honoured at the prestigious Classic Brits Awards held in London’s Royal Albert Hall for his “Outstanding Contribution to Classical Music” in celebration of his 30 years as one of the top classical musicians of our time. -- Biography (text only) taken from the Deutsche

Grammophon website

|

BD: Do you succeed?

BD: Do you succeed? BD: Can we always assume he will sing it perfectly

in the theater?

BD: Can we always assume he will sing it perfectly

in the theater? BD: Is there anything you can do to overcome a bad

acoustic?

BD: Is there anything you can do to overcome a bad

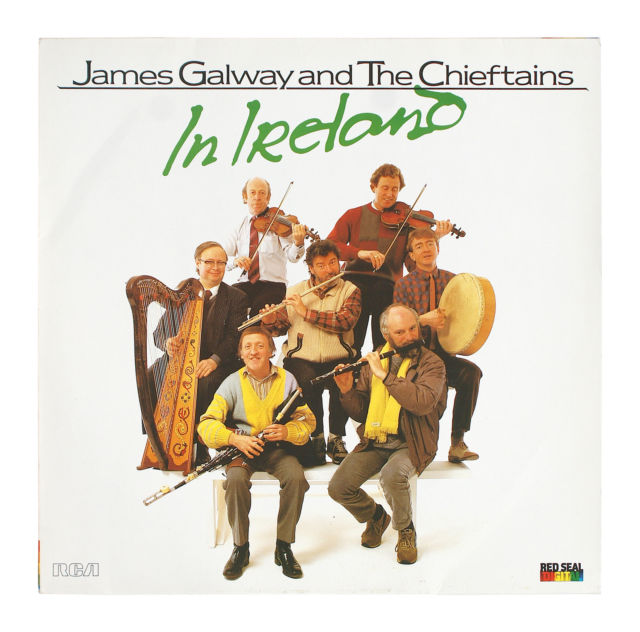

acoustic? BD: There are Irish tenors.

Are you an Irish flute player?

BD: There are Irish tenors.

Are you an Irish flute player? JG: Just by the fact that they

listen to records, and they achieve that standard in their twenties.

Then they bring it up a bit, and the next lot go up to that by

listening to records, and so on. Also, the teaching has become

more explicit. Fifty years ago, people would ask if they should

play with vibrato or not, and inquire about how to do this. Often,

they would just try it. People used to play long tones. I

don’t play ‘long tones’. I play shorter ones, because even if you

can play a long tone for the rest of the week, unless you change it, it

ain’t going to get better! So, you have to change it like a singer.

A singer doesn’t stand and go [humming a constant tone to demonstrate]

for half an hour. They change it, and flute players are now beginning

to do the same thing. We’re beginning to find out that it’s better

to change the note, and not play these long tones, as they were known.

JG: Just by the fact that they

listen to records, and they achieve that standard in their twenties.

Then they bring it up a bit, and the next lot go up to that by

listening to records, and so on. Also, the teaching has become

more explicit. Fifty years ago, people would ask if they should

play with vibrato or not, and inquire about how to do this. Often,

they would just try it. People used to play long tones. I

don’t play ‘long tones’. I play shorter ones, because even if you

can play a long tone for the rest of the week, unless you change it, it

ain’t going to get better! So, you have to change it like a singer.

A singer doesn’t stand and go [humming a constant tone to demonstrate]

for half an hour. They change it, and flute players are now beginning

to do the same thing. We’re beginning to find out that it’s better

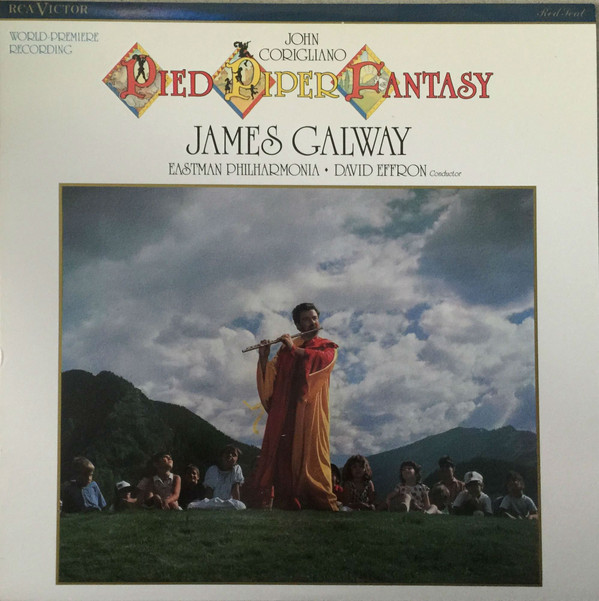

to change the note, and not play these long tones, as they were known. JG: Even without the dramatics,

it’s a more serious piece. Everybody thinks the Pied Piper Fantasy

is a fun piece, when in actual fact, the story of the Pied Piper is

a Mediaeval horror show. This guy comes along and says he’ll get

rid of the rats, and they agree to pay the money. Then, they don’t

pay him the money, so he takes away the real life of the whole town by

removing all the children. Imagine a town with nobody under twenty-five!

Everybody thinks this Pied Piper is a fun guy because he’s dressed up

in all his colors, but he’s not funny at all. He’s a very, very

serious fellow.

JG: Even without the dramatics,

it’s a more serious piece. Everybody thinks the Pied Piper Fantasy

is a fun piece, when in actual fact, the story of the Pied Piper is

a Mediaeval horror show. This guy comes along and says he’ll get

rid of the rats, and they agree to pay the money. Then, they don’t

pay him the money, so he takes away the real life of the whole town by

removing all the children. Imagine a town with nobody under twenty-five!

Everybody thinks this Pied Piper is a fun guy because he’s dressed up

in all his colors, but he’s not funny at all. He’s a very, very

serious fellow.|

“Halil is formally unlike any other work I have written,

but it is like much of my music in its struggle between tonal and non-tonal

forces. In this case I sense that struggle as involving wars and the

threats of wars, the overwhelming desire to live and the consolations

of art, love, and the hope for peace. I never knew Yadin Tannenbaum, but

I know his spirit.” -- Leonard Bernstein

|

JG: Yes, but it’s traditional because

when you’re a little kid, and you go along for a flute lesson, and

your teacher has a hangover from the day before, you start playing your

tune and he says, “[gruffly] Play an accent on the

first note of each bar!” [Demonstrates such

exaggerated accents amid much laughter] So you go away thinking that’s

it. The other thing is the breathing, which is also traditional from

childhood, because you have to figure out a way to show a twelve-year

old student how to play. For example, let us take a slow movement

of a Bach sonata. You know very well that this child will not be

able to manage the breathing like an adult, so you have to figure breaths.

But then the trouble is they grow up, and in the meantime they don’t take

the breaths out. They keep them in.

JG: Yes, but it’s traditional because

when you’re a little kid, and you go along for a flute lesson, and

your teacher has a hangover from the day before, you start playing your

tune and he says, “[gruffly] Play an accent on the

first note of each bar!” [Demonstrates such

exaggerated accents amid much laughter] So you go away thinking that’s

it. The other thing is the breathing, which is also traditional from

childhood, because you have to figure out a way to show a twelve-year

old student how to play. For example, let us take a slow movement

of a Bach sonata. You know very well that this child will not be

able to manage the breathing like an adult, so you have to figure breaths.

But then the trouble is they grow up, and in the meantime they don’t take

the breaths out. They keep them in.|

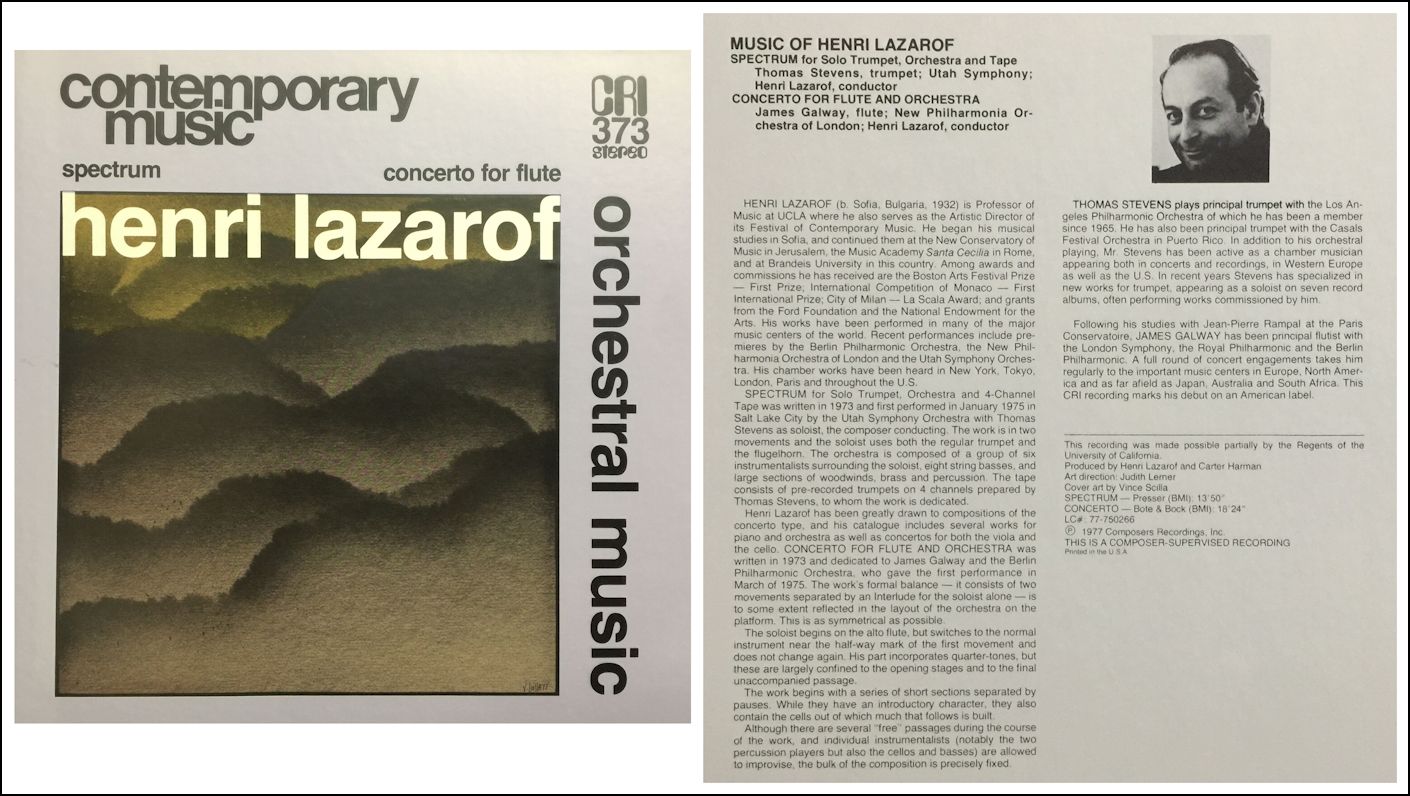

Born in Chicago, Phillip Moll lives in Berlin, working as an accompanist and ensemble pianist and collaborating with such diverse artists as Kyung Wha Chung, Anne-Sophie Mutter, Sir James Galway, Kurt Moll (!), and Jessye Norman. He has performed and recorded with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the German Symphony Orchestra, the RIAS Chamber Choir and the Berlin Radio Choir. Performances have taken him throughout Europe, North America and the Far East. After receiving degrees in English from Harvard University and in music from the University of Texas, and following a year at the Hochschule für Musik in Munich, Moll was employed as a repetiteur by the German Opera in Berlin until 1978. Since then he has been active as an accompanist and ensemble pianist, and beginning in 2004 he has held a professorship for song interpretation at the Leipzig Hochschule. |

|

Prior to the development of the Boehm system, flutes were most commonly made of wood, with an inverse conical bore, eight keys, and tone holes that were small in size, and thus easily covered by the fingertips. Boehm's work was inspired by an 1831 concert in London, given by soloist Charles Nicholson who, with his father in the 1820s, had introduced a flute constructed with larger tone holes than were used in previous designs. This large-holed instrument could produce greater volume of sound than other flutes, and Boehm set out to produce his own large-holed design. In addition to large holes, Boehm provided his flute with "full venting", meaning that all keys were normally open. Previously, several keys were normally closed, and opened only when the key was operated. Boehm also wanted to locate tone holes at acoustically optimal points on the body of the instrument, rather than locations conveniently covered by the player's fingers. To achieve these goals, Boehm adapted a system of axle-mounted keys with a series of "open rings" (called brille, German for "eyeglasses", as they resembled the type of eyeglass frames common during the 19th century) that were fitted around other tone holes, such that the closure of one tone hole by a finger would also close a key placed over a second hole. |

BD: When you perform pieces of music,

you know how you want to interpret then. Does that style, or

do those ideas change after ten, or fifteen, or twenty years?

BD: When you perform pieces of music,

you know how you want to interpret then. Does that style, or

do those ideas change after ten, or fifteen, or twenty years?

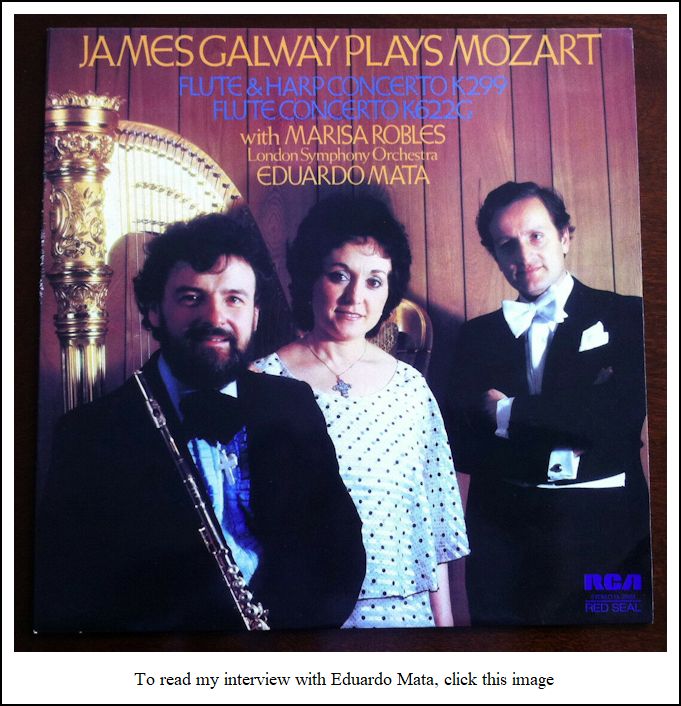

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Orchestra Hall, Chicago, on April 21, 1989. Portions were broadcast on WNIB later that year, and again in 1990, 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.