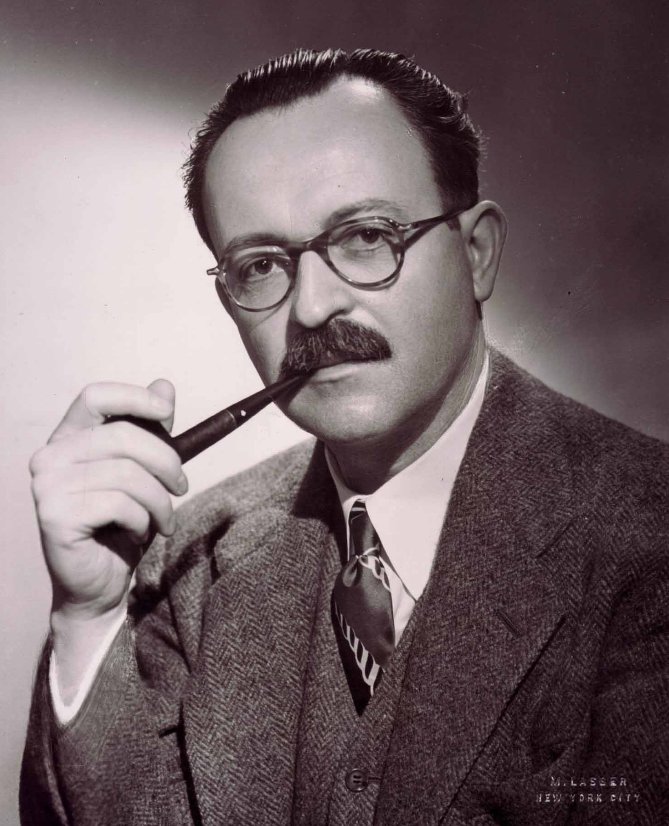

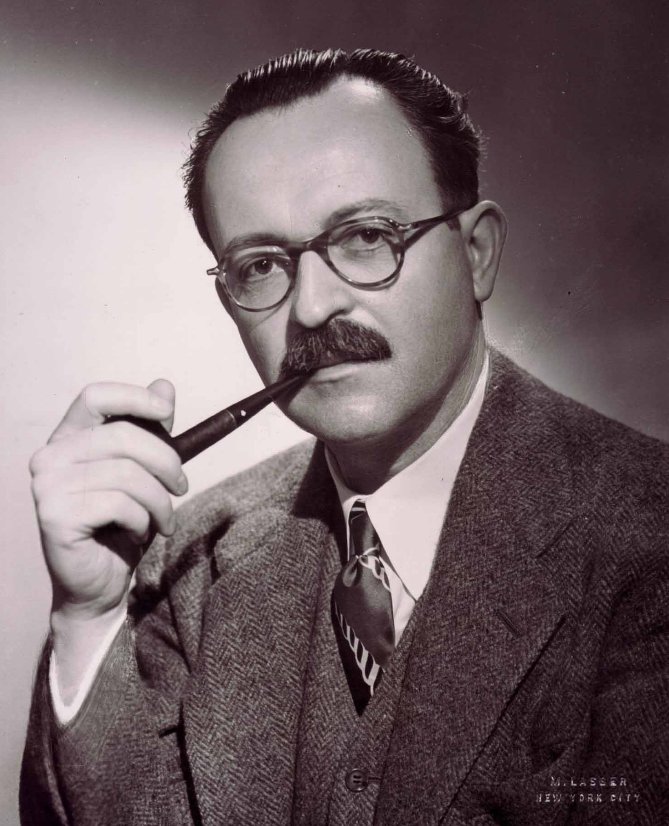

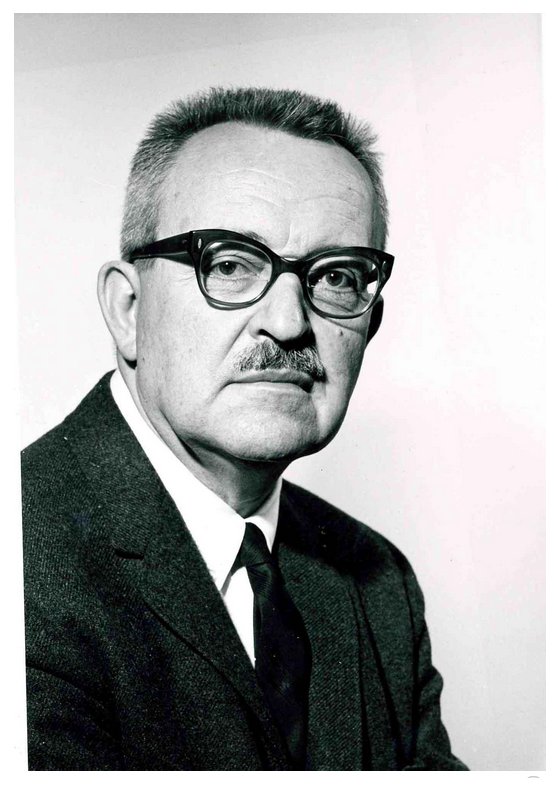

| NORMAND LOCKWOOD (1906-2002) was

born in New York City, but grew up in Ann Arbor. His uncle, a pianist, and

father, a violinist, headed their respective departments at the University

of Michigan's School of Music. In his late teens, he began to study composition under Ottorino Respighi in Rome and, for three years, in Paris with Nadia Boulanger. A year later, he won the Rome prize from the American Academy in Rome. He taught at Oberlin College, Columbia College, Union Theological Seminary's School of Sacred Music, Westminster Choir College, Yale School of Music, Trinity University, San Antonio, the Universities of Oregon and Hawaii, and at the University of Denver until retirement from that institution as Professor Emeritus. Lockwood was active at Yaddo (Saratoga Springs), and the Composers' Conference and Chamber Music Center (Middlebury), and in the National Association for American Composers and Conductors, and the American Composers Alliance. He was a Guggenheim Fellow, and counts among his honors the Marjorie Peabody Waite Award from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. |

BD: I just wondered if there was any other instrument

that could be used with an accordion.

BD: I just wondered if there was any other instrument

that could be used with an accordion.

NL: I don’t know. I was so young and

inexperienced at the time. In spite of being musical, which I certainly

was with my background and all, I don’t think I got a great deal from him.

It’s a funny thing. I don’t believe a word of it, but musicians repeatedly

speak of my having a very keen sense of instrumental of orchestral writing

and treatment. So I must have, and this must have had an influence on

me. My music doesn’t come out like Respighi’s. It never did, but

that doesn’t matter. There are certain principles that one can learn

without putting on the clothes of someone else, so it must have had a great

effect. I got the most out of Nadia Boulanger, whom I studied with

for a few years, and then again a few times off and on. She put me

through some disciplines; she made me work the hell out of counterpoint.

That’s what I needed, and also the study of musical analysis. Those

two factors are what I got most out of her.

NL: I don’t know. I was so young and

inexperienced at the time. In spite of being musical, which I certainly

was with my background and all, I don’t think I got a great deal from him.

It’s a funny thing. I don’t believe a word of it, but musicians repeatedly

speak of my having a very keen sense of instrumental of orchestral writing

and treatment. So I must have, and this must have had an influence on

me. My music doesn’t come out like Respighi’s. It never did, but

that doesn’t matter. There are certain principles that one can learn

without putting on the clothes of someone else, so it must have had a great

effect. I got the most out of Nadia Boulanger, whom I studied with

for a few years, and then again a few times off and on. She put me

through some disciplines; she made me work the hell out of counterpoint.

That’s what I needed, and also the study of musical analysis. Those

two factors are what I got most out of her. NL: As far as opera’s effect, I think there

are two conditions. One of them is viewing opera. After all, it’s

a staged work and it has to be seen either on the stage or on television.

Listening to the music of opera on records or over the air is an entirely

different matter because there is one essential ingredient missing.

That being the case, I think where opera is going is rather to be accepted.

It must be highly lyrical and attractive from a purely orchestral, instrumental

standpoint, because you don’t have the vision there. This is what opera

will need and therefore is what it should have. The Italian operas have

taken a crack at it by a great many people since Wagner and Strauss, and

most of all by Debussy, whose remarkable Pelléas and Mélisande is

totally foreign to bel canto Italian opera.

NL: As far as opera’s effect, I think there

are two conditions. One of them is viewing opera. After all, it’s

a staged work and it has to be seen either on the stage or on television.

Listening to the music of opera on records or over the air is an entirely

different matter because there is one essential ingredient missing.

That being the case, I think where opera is going is rather to be accepted.

It must be highly lyrical and attractive from a purely orchestral, instrumental

standpoint, because you don’t have the vision there. This is what opera

will need and therefore is what it should have. The Italian operas have

taken a crack at it by a great many people since Wagner and Strauss, and

most of all by Debussy, whose remarkable Pelléas and Mélisande is

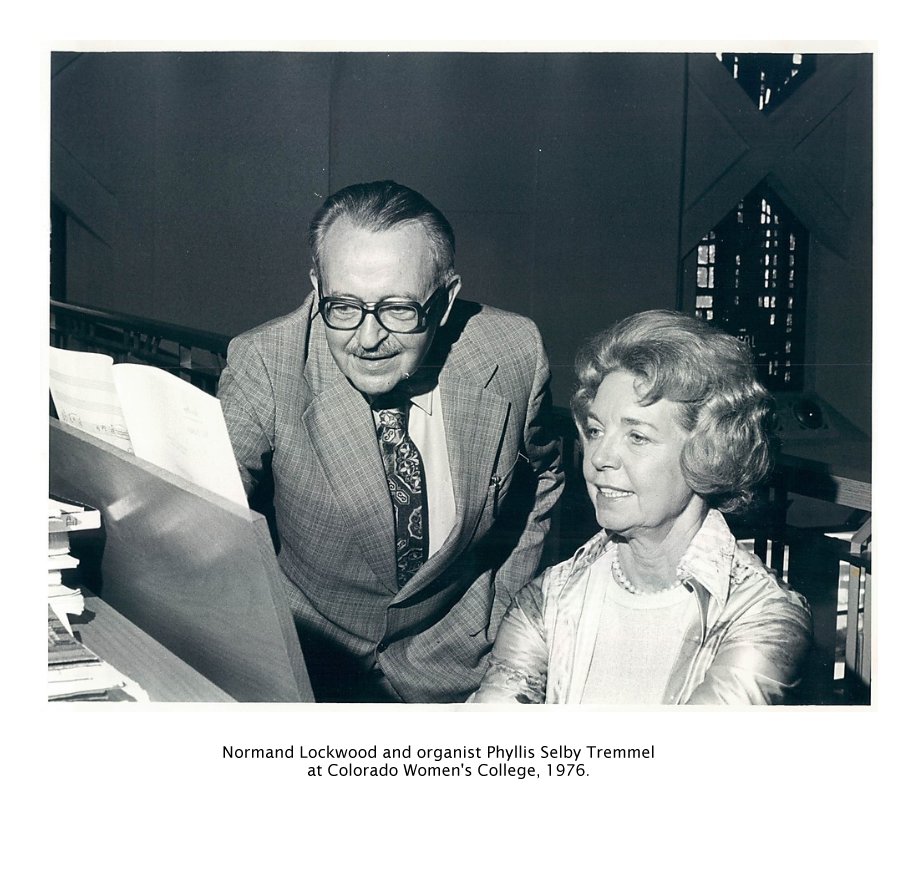

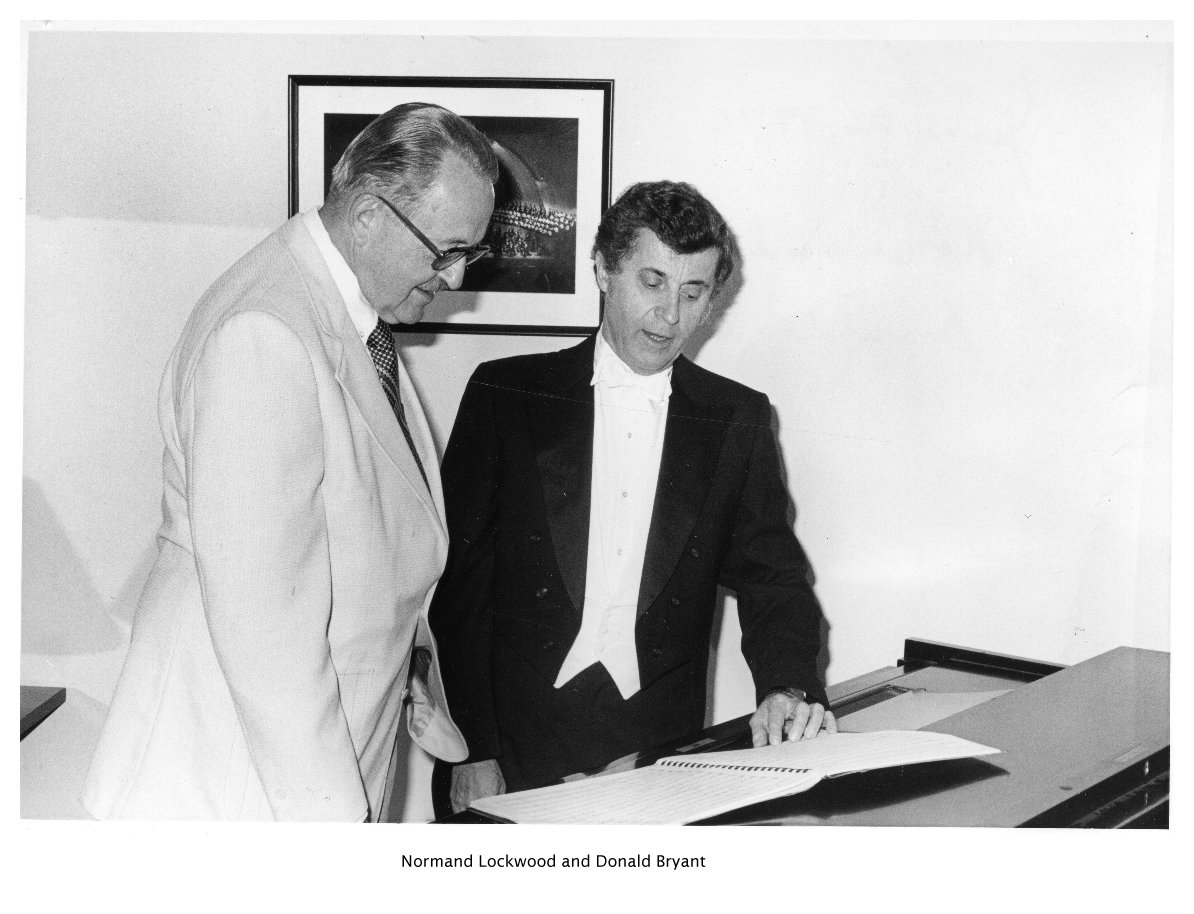

totally foreign to bel canto Italian opera.| Normand Lockwood was born in New

York City on March 19, 1906, but raised in Ann Arbor, Mich. from the age

of two. He was the son of Angelina (Normand-Smith) and Samuel Pierson Lockwood.

Samuel Lockwood was a violinist, teacher, and conductor at the University

of Michigan's School of Music in Ann Arbor, Mich. Angelina was also a violinist

and played in the school orchestra and faculty string quartet at the University

of Michigan though she was not a member of the faculty. Normand Lockwood attended elementary school in Ann Arbor, Mich. While there, he began studying piano under Otto J. Stahl, who was the first to encourage Lockwood to write music. Through his father, Lockwood was able to pursue music classes at the University of Michigan. In 1924, Lockwood's academic education ended after two years at Ann Arbor High School. Traveling in Europe with his uncle, pianist Albert Lockwood, Lockwood ended up in Rome where he studied orchestration with Ottorino Respighi for one year (1924-25). Lockwood next studied composition under Nadia Boulanger in Paris (1926-28, 1930-32). Under Boulanger, Lockwood's talent blossomed. During this period of schooling, Lockwood married Dorothy Sanders on September 21, 1926, with whom he raised three children. The marriage ended in 1955. Lockwood was the recipient of the Prix de Rome fellowship in composition from 1929-32 at the American Academy in Rome. In 1932, Lockwood returned to the United States as Assistant Professor in theory and composition at Oberlin College, Ohio. From 1942 to 1948, he moved to New York as recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship studying and composing, holding faculty positions and lecturing at Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary, and composing and arranging music for CBS. In 1948 Lockwood was appointed Head of Composition and Theory at Westminster Choir College, Princeton, NJ. From 1950-52 he was visiting professor and lecturer at Queens College and Yale University. He also received many awards for compositions during this period. In 1953-55 Lockwood was named Chair of the Music Department, Trinity University, San Antonio, Texas. From 1955-57 he moved to Laramie, Wyoming, where he composed many pieces of music. He also met and married Vona K. Swedell. From 1957 to 1961, Lockwood was visiting professor at the University of Oregon, University of Hawaii, and began his relationship with the University of Denver. In 1961 he received a joint faculty appointment in the departments of Music and Drama at the University of Denver where he produced many operatic/theatrical works. Lockwood retired and became Professor Emeritus at the University of Denver in 1974. Normand Lockwood lived in Denver, Colorado, with his wife, Vona, and continued to compose music from the time of his retirement in 1974 until his death in 2002. He has composed over 500 works in all traditional musical genres, including choral, keyboard, chamber music, solo songs, works for large instrumental ensembles, operas, and incidental music for drama. He died in Denver on March 9, 2002, ten days shy of his 96th birthday. |

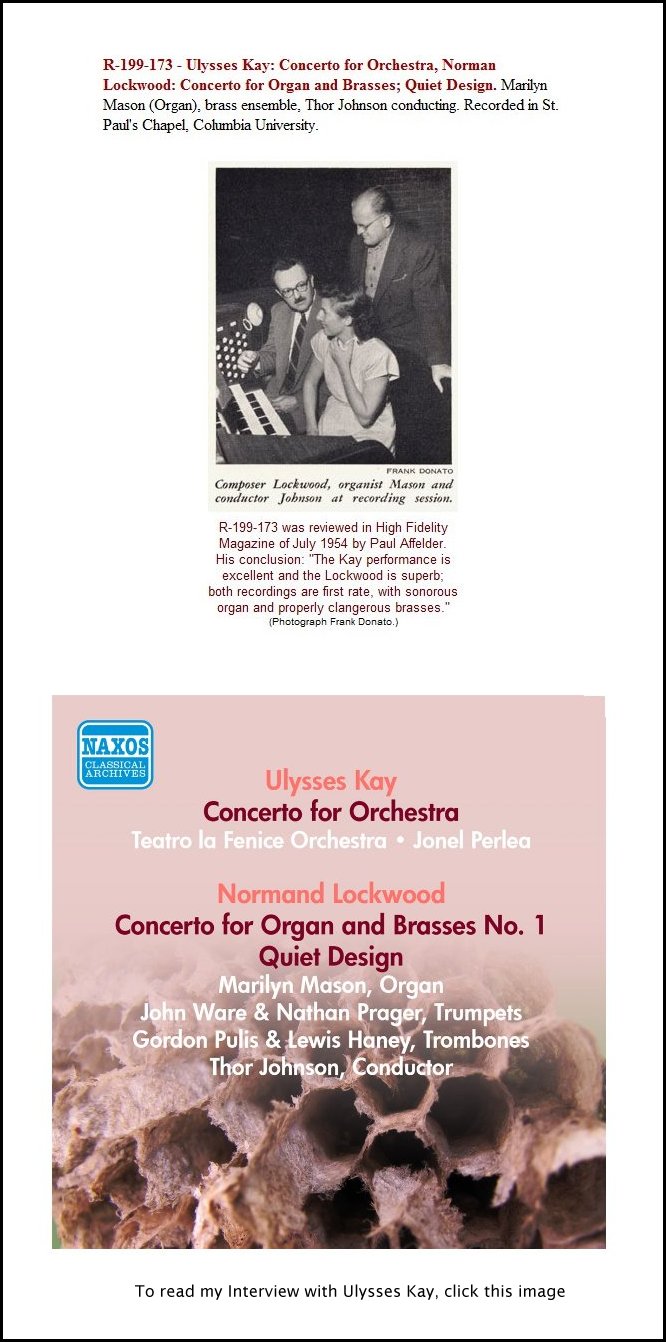

This interview was recorded on the telephone on February

12, 1986. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB two months

later, as well as in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made and

posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.