DG: I can't do everything that I'm offered, so

I try to pick and choose. It's a question of idiomatic writing for

the voice more than anything. The first half of this century brought

a lot of experimentation for a lot of reasons both musical and non-musical.

Now, in the second half of the century, there seems to be a movement, first

of all, a return to a traditional concept of beauty, which is very welcome.

Along with that comes an idea of writing for the beauty of the voice.

I remember seeing Charles Reiner, the well-known Canadian pianist, play a

contemporary concert ten years ago. He was there in white tie and tails,

and he did nothing during one piece but roll tennis balls around on the strings

of the piano. This is useless. It ignores the potential of the

piano and certainly ignores the potential of Charles Reiner. I feel

the same way about singing.

DG: I can't do everything that I'm offered, so

I try to pick and choose. It's a question of idiomatic writing for

the voice more than anything. The first half of this century brought

a lot of experimentation for a lot of reasons both musical and non-musical.

Now, in the second half of the century, there seems to be a movement, first

of all, a return to a traditional concept of beauty, which is very welcome.

Along with that comes an idea of writing for the beauty of the voice.

I remember seeing Charles Reiner, the well-known Canadian pianist, play a

contemporary concert ten years ago. He was there in white tie and tails,

and he did nothing during one piece but roll tennis balls around on the strings

of the piano. This is useless. It ignores the potential of the

piano and certainly ignores the potential of Charles Reiner. I feel

the same way about singing. DG: Right. One piece I've done several times

is for tenor, percussion and synthesized tape, and it's great! People

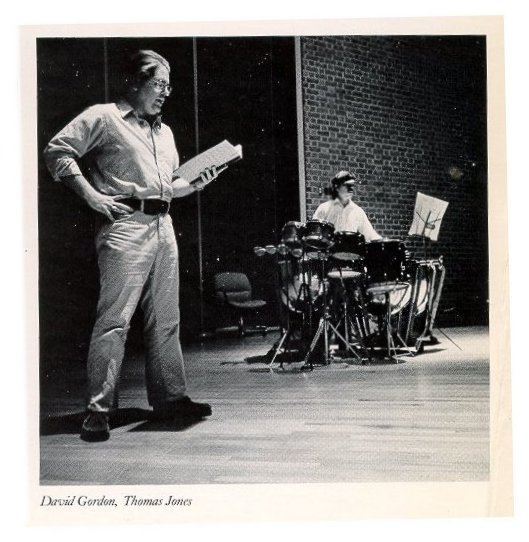

really dig it. [This is Cantata for

Tenor Voice, Percussion, and Electronic Sounds by Maurice Wright.

It was recorded as part of a two-LP set on Smithsonian Collection Records

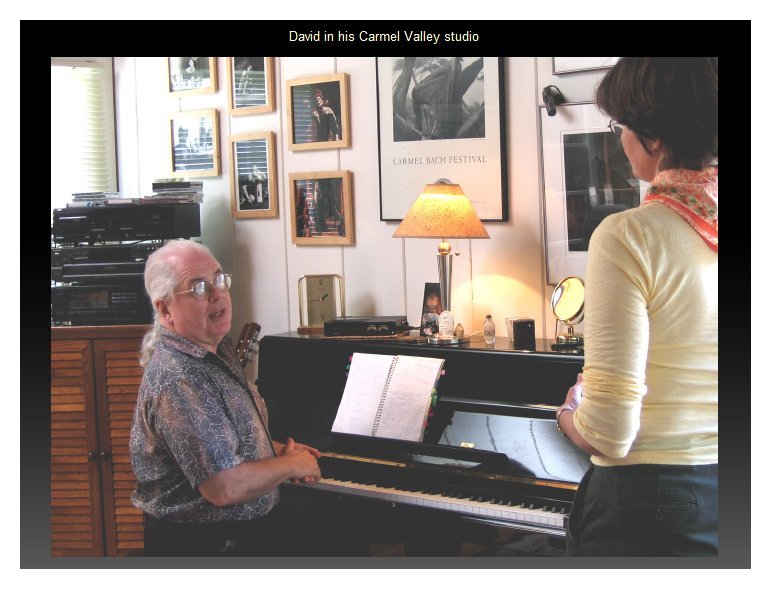

by the 20th Century Consort, as seen in the photo at left. Gordon was

also featured with the same group on their recording of Into Eclipse by Stephen Albert which was

later issued on Nonesuch Records.] It's something that audiences can

enjoy on first hearing. The greatest compliment I can get is when someone

has been dragged to the concert and then really enjoys the piece! So

I think it's up to me as a performer to do more of this kind of music so

people will hear it and like it and come to know and have a better outlook

for it. I'm very committed to this music and it's a wonderful change

from opera. It disciplines you in a very good way.

DG: Right. One piece I've done several times

is for tenor, percussion and synthesized tape, and it's great! People

really dig it. [This is Cantata for

Tenor Voice, Percussion, and Electronic Sounds by Maurice Wright.

It was recorded as part of a two-LP set on Smithsonian Collection Records

by the 20th Century Consort, as seen in the photo at left. Gordon was

also featured with the same group on their recording of Into Eclipse by Stephen Albert which was

later issued on Nonesuch Records.] It's something that audiences can

enjoy on first hearing. The greatest compliment I can get is when someone

has been dragged to the concert and then really enjoys the piece! So

I think it's up to me as a performer to do more of this kind of music so

people will hear it and like it and come to know and have a better outlook

for it. I'm very committed to this music and it's a wonderful change

from opera. It disciplines you in a very good way.|

David Gordon at Lyric Opera of Chicago

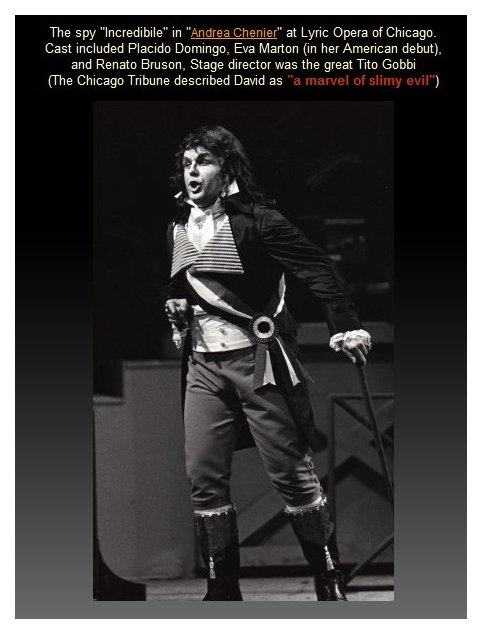

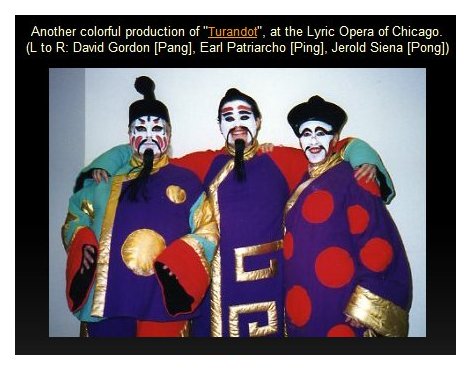

1973 - Rosenkavalier (Major Domo of Fanninal) with Ludwig/Dernesch, Berthold, Sotin, Blegen; Leitner 1979 - Andrea Chénier (Incredible) with Domingo, Marton, Bruson; Bartoletti; Gobbi

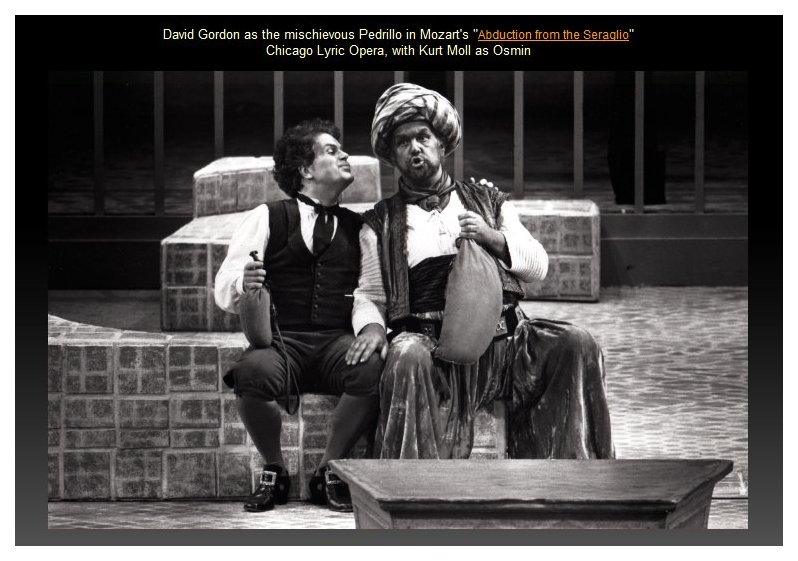

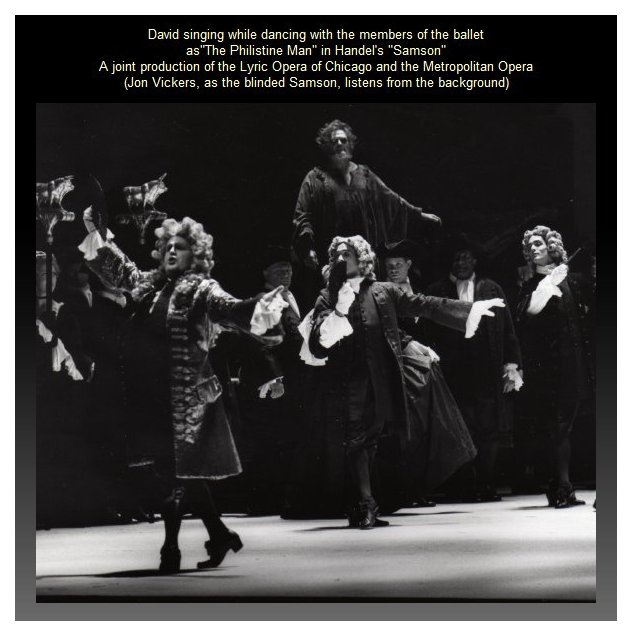

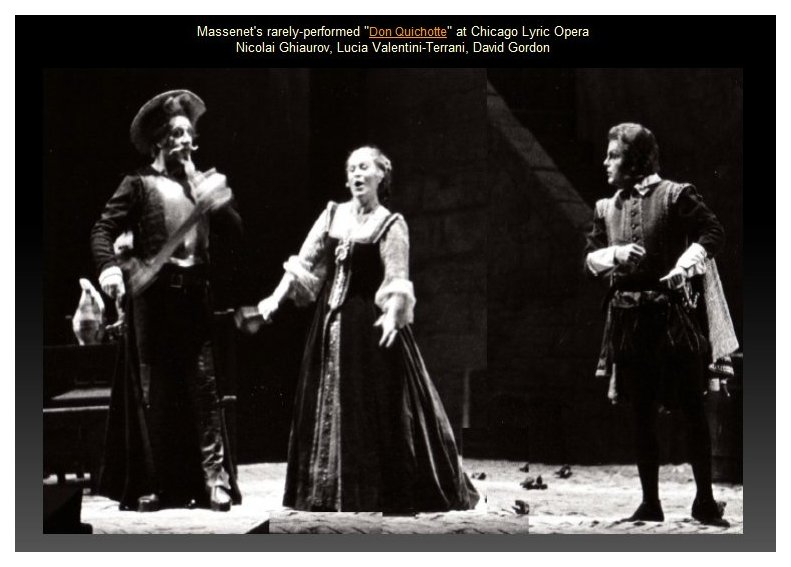

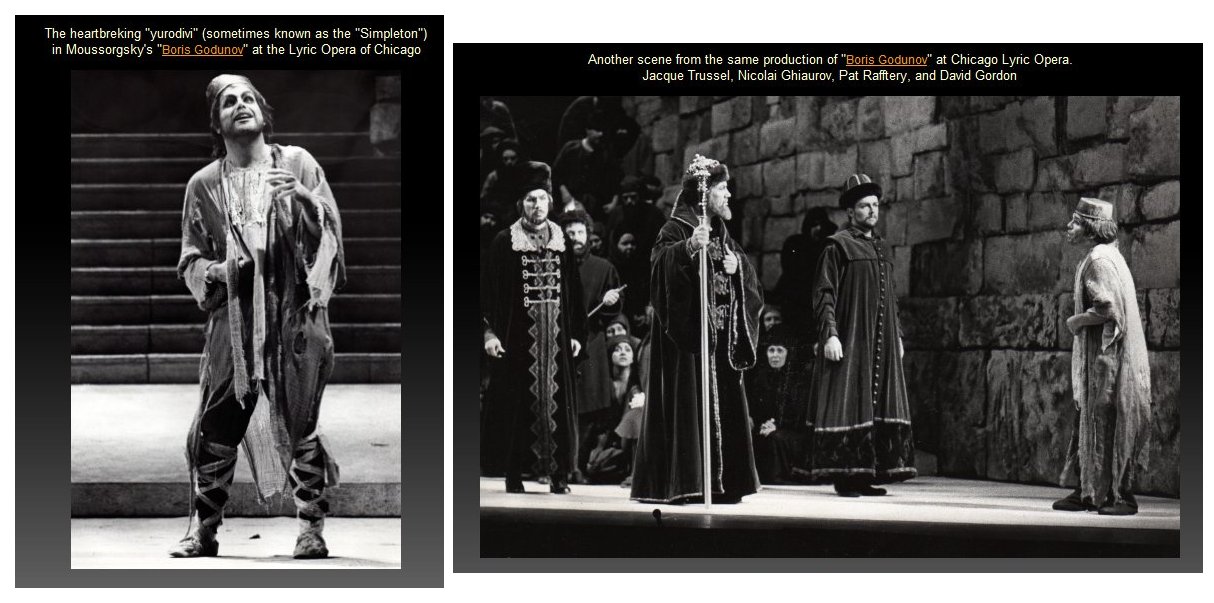

1980 - Boris Godunov [Opening Night] (Simpleton) with Ghiaurov, Baldani, Ochman, Sotin, Trussel; Bartoletti; Everding 1981 - Ariadne auf Naxos (Scaramuccio) with Meier/Rysanek, Minton, Johns, Welting; Janowski Don Quichotte (Juan) with Ghiaruov, Gramm, Valentini-Terrani, Cook, Negrini; Fournet Elisir d'Amore [Student matinees] (Nemorino) with Hines, Raftery; Schaenen 1982 - Pagliacci (Beppe) with Vickers, Barstow, MacNeil, Carlson; Cillario 1984 - Abduction from the Seraglio (Pedrillo) with Welting, Araiza, Moll; Leitner 1985-86 - Samson [Handel] (Philistine Man) with Vickers, Shade, Anderson, Howell, Plishka; Rudel

1994-94 - Boris Godunov [Opening Night] (Simpleton) with Ramey, Kavrakos, Denniston; Bartoletti 1996-97 - Turandot (Pang) with Schnaut, Heppner, Esperian, Anisimov, Cangelosi; Bartoletti

[Note: The lighting in most of these productions was designed by Duane Schuler.] Also, during the seasons 1974 -80, Gordon participated in several "Outreach" performances at schools and other local venues presented by Lyric Opera. The repertoire included Il Ciarlitano (Ernesto) by Domenico Puccini [American Premiere], Barber of Seville (Almaviva), La Traviata (Alfredo), and Don Pasquale (Ernesto). |

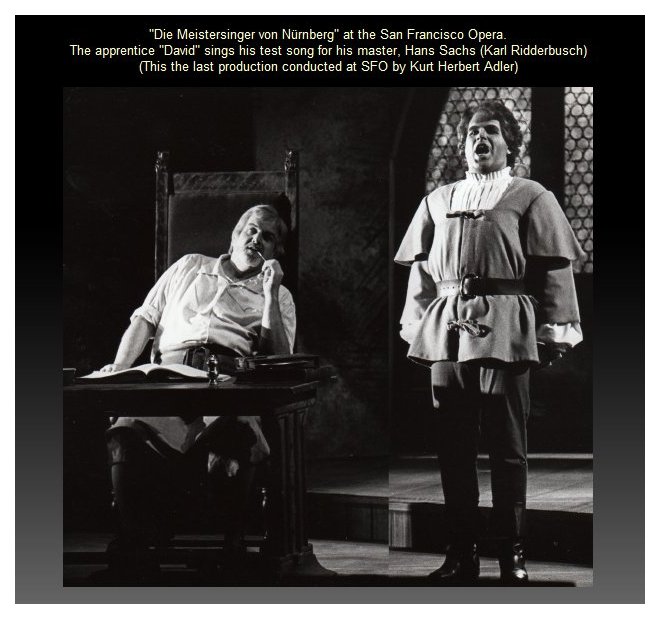

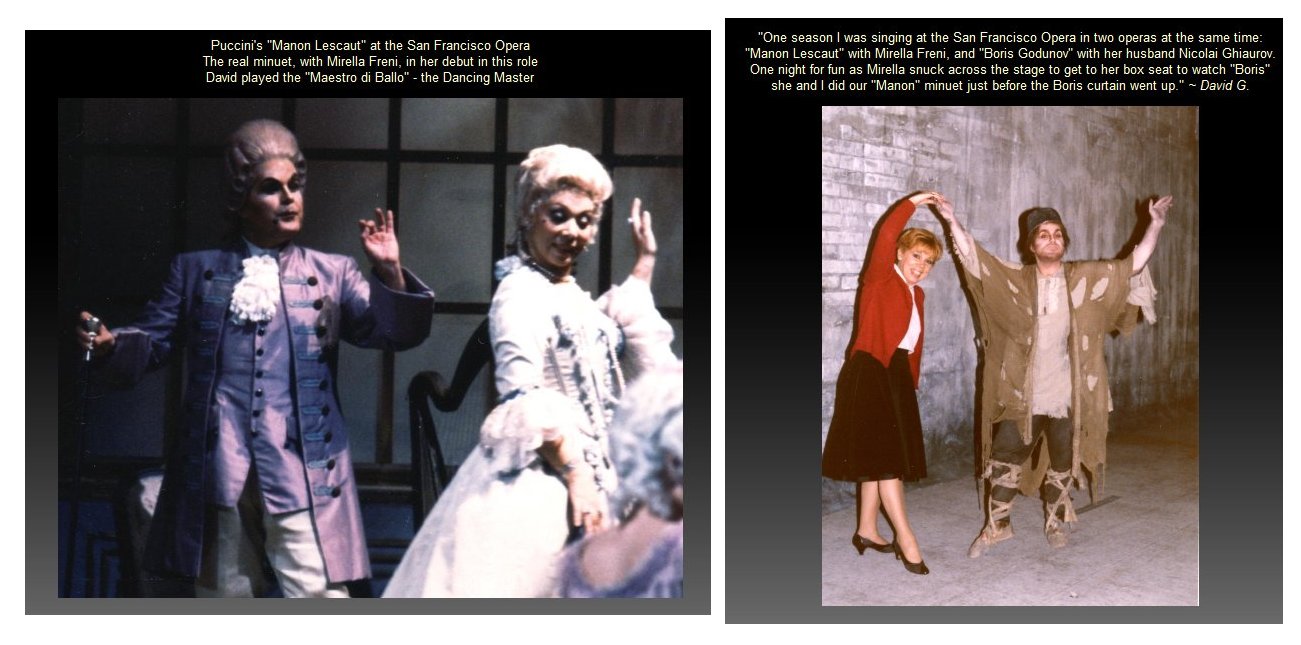

David Gordon at the San Francisco Opera

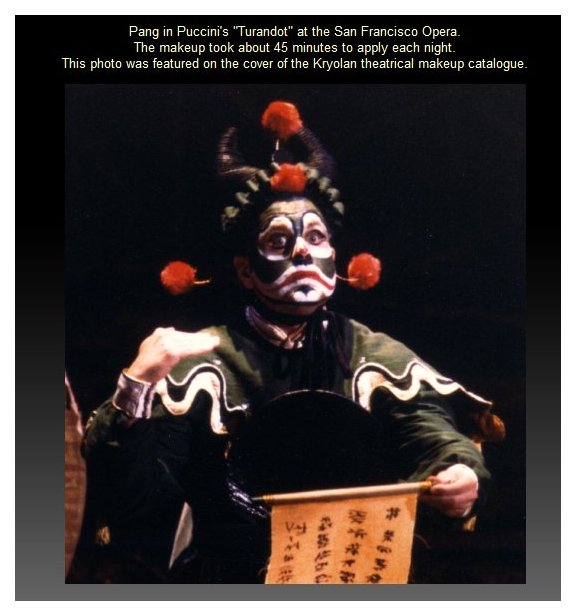

1981 (Summer) - Die Meistersinger (David) with Ridderbusch, Bode, Johns, Rydl, Hornik, Del Carlo, Halfvarson; Adler Rigoletto (Borsa) with Boyagian/Manuguerra, Wise, Dvorský, Rydl; Bareza 1982 (Summer) - Turandot (Pang) with Kelm, Daniels, Martinucci; Chung

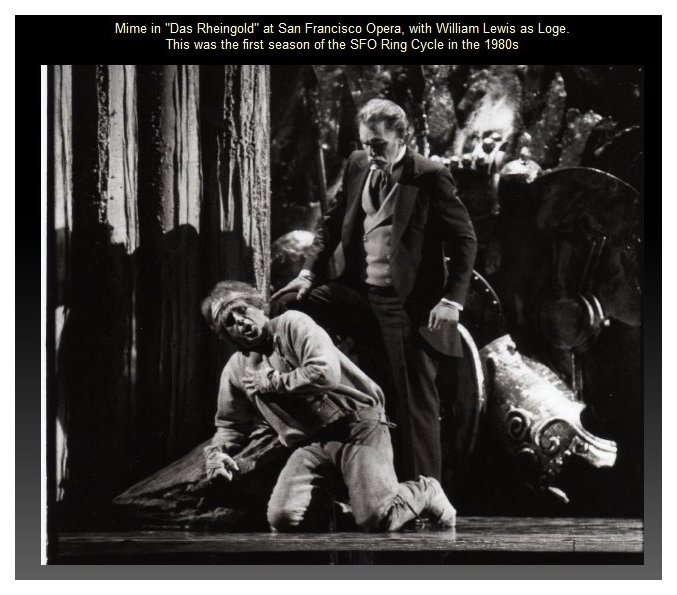

1983 - Ariadne auf Naxos (Brighella) with Plowright/De Vol/Reppel, Bailey/Johns, Quittmeyer, Berry, Battle; Dohnányi Boris Godunov (Simpleton) with Ghiaurov, Tomlinson, Ochman, Mineva; Janowski Manon Leascut (Dancing Master) with Freni, Mauro, Sardinero, Capecchi; Arena The Rake's Progress [Portion of performance as cover] (Tom Rakewell) with Soviero, Gramm, Dunn; Agler 1983 (Summer) - Das Rheingold (Mime) with Devlin, Berry, Lewis, Schwarz; de Waart

1986 - Die Meistersinger (David) with Tschammer, Studer, King, Rydl, Trempont, Del Carlo; Adler 1986 (Summer) - Pagliacci (Beppe) with Mauro, Soviero, Cappuccilli, Malis; Guadagno 1990 - Pagliacci (Beppe) with Atlantov, Mims, Manuguerra/Noble, G. Quilico; Santi |

BD: What was your reaction on realizing you'd be

singing that role with those people?

BD: What was your reaction on realizing you'd be

singing that role with those people?|

David Gordon

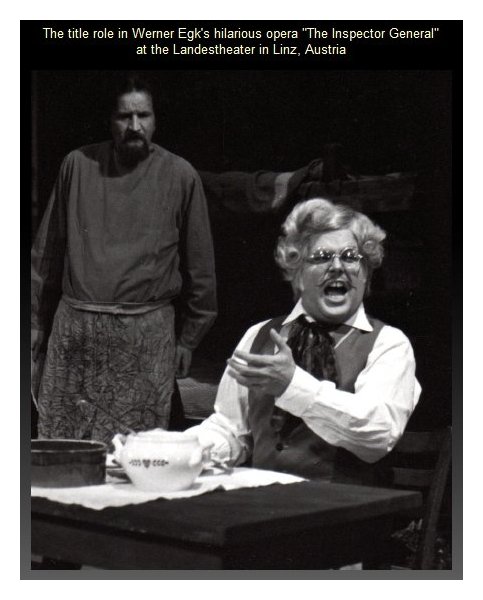

Repertoire at the Linz Opera

May 1975 - June 1979

[All operas sung in German] Cornelius - Der Barbier von Bagdad (Mustafa) D'Albert - Tiefland (Nando) Eder - Der Aufstand (Jester, Grave Robber) Egck - Der Revisor (Chlestakov)

Kienzl - Der Evangelimann (Hans) Leoncavallo - Pagliacci (Beppe) Mozart - Così fan tutte (Ferrando) Pfitzner - Palestrina (Abdisu, Isaac, and two other roles) Puccini - La Bohème (Parpignol) Rossini - Il Barbiere di Siviglia (Almaviva) Smetana - Bartered Bride (Vašek) Strauss - Ariadne auf Naxos (Tanzmeister, Brighella) Strauss - Die Schweigsame Frau (Henry) Szokolay - Bluthochzeit (The Moon) Verdi - La Traviata (Gastone) Wagner - Lohengrin (2nd nobleman of Brabant) Wolf-Ferrari - Die vier Grobiane (Filipeto) |

DG: Well, I can't say. I've sung only

in English and German speaking countries, and I've been working equally hard

on those two equally difficult languages. I prefer, as a singer, to

sing in Italian because it's the nicest language to sing in. I'm happy

to be doing Elisir (here in Chicago)

in Italian.

DG: Well, I can't say. I've sung only

in English and German speaking countries, and I've been working equally hard

on those two equally difficult languages. I prefer, as a singer, to

sing in Italian because it's the nicest language to sing in. I'm happy

to be doing Elisir (here in Chicago)

in Italian. DG: There are operas written in the twentieth century

that are good. Peter Grimes

is a great opera, and I don't use the term "great" lightly.

DG: There are operas written in the twentieth century

that are good. Peter Grimes

is a great opera, and I don't use the term "great" lightly. DG: It's hard. It's very hard for my personal

life and my wife and I have to work at it all the time because we are apart

so much. I don't enjoy superficial relationships. I find them

distracting and draining. I think our aim is to have my wife come with

me for longer periods, but she has her own career and I don't want her to

just sit around while I go off to perform. It's not an easy life for

a singer in the States because you're traveling all the time.

DG: It's hard. It's very hard for my personal

life and my wife and I have to work at it all the time because we are apart

so much. I don't enjoy superficial relationships. I find them

distracting and draining. I think our aim is to have my wife come with

me for longer periods, but she has her own career and I don't want her to

just sit around while I go off to perform. It's not an easy life for

a singer in the States because you're traveling all the time.

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded at his hotel on November 20, 1981.

Segments were used (with recordings) on WNIB in 1987, 1989, 1992, and 1997.

Portions were transcribed and published in Wagner News in April, 1982, and in Opera Scene in November, 1982. The

full transcription was re-edited and posted on this website in 2013.

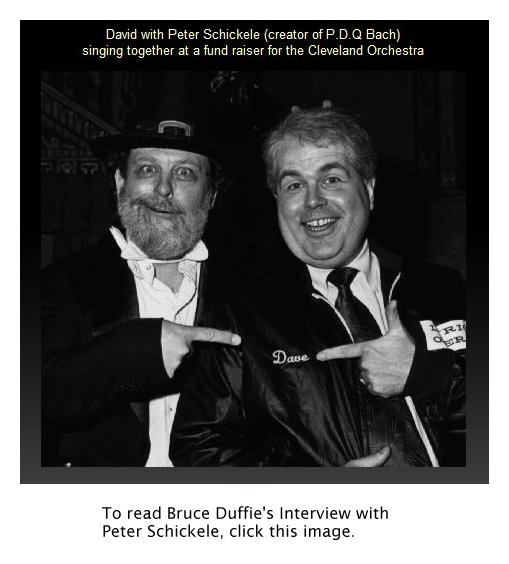

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.