|

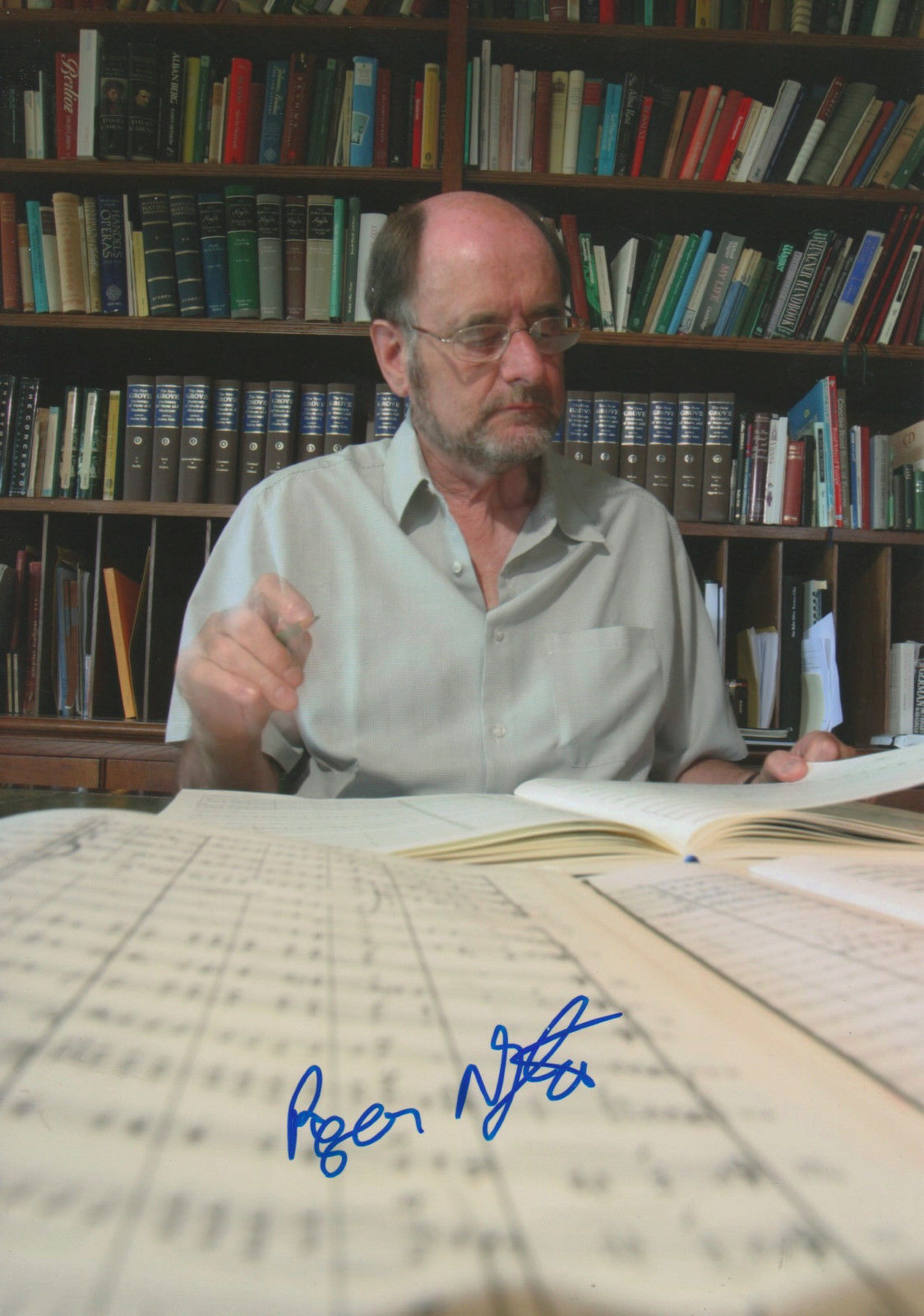

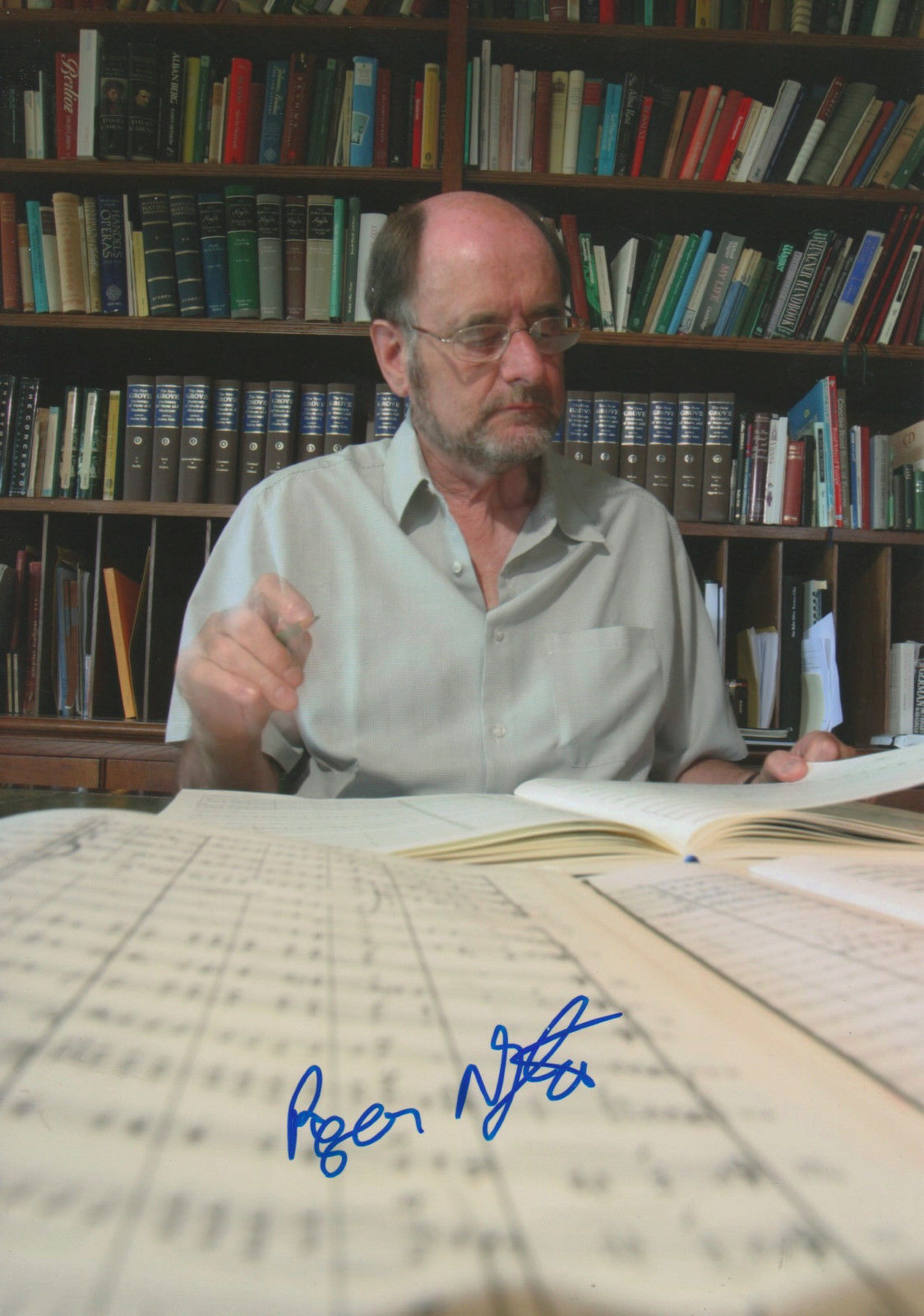

Sir Roger Arthur Carver Norrington was born in Oxford March 16, 1934, and comes from a musical University family. He was a talented boy soprano, studying the violin from the age of ten and singing from the age of seventeen. He read English Literature at Cambridge University, and spent several years as an amateur violinist, tenor singer, and conductor, before attending the Royal College of Music as a postgraduate student of conducting, studying with Sir Adrian Boult.

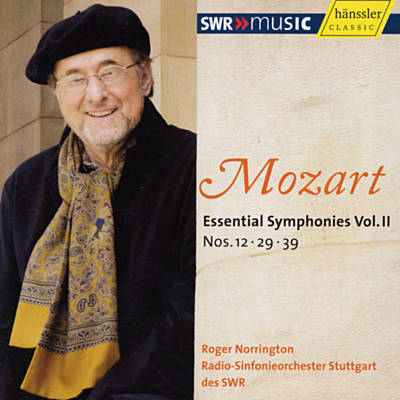

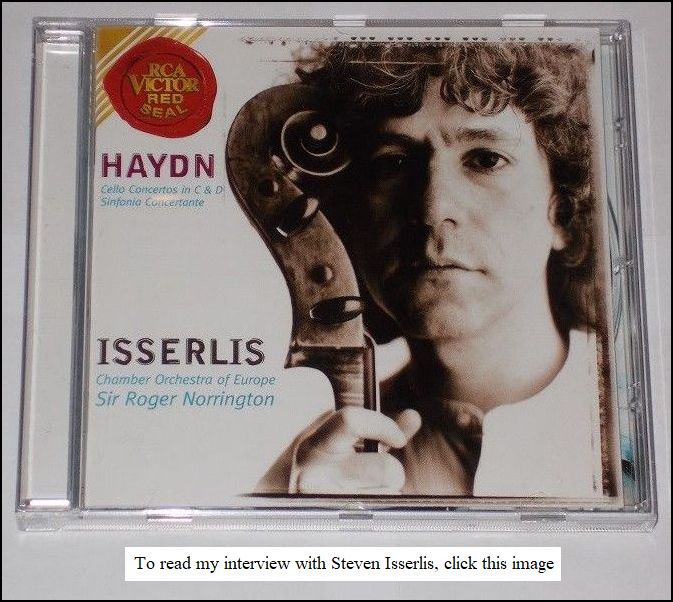

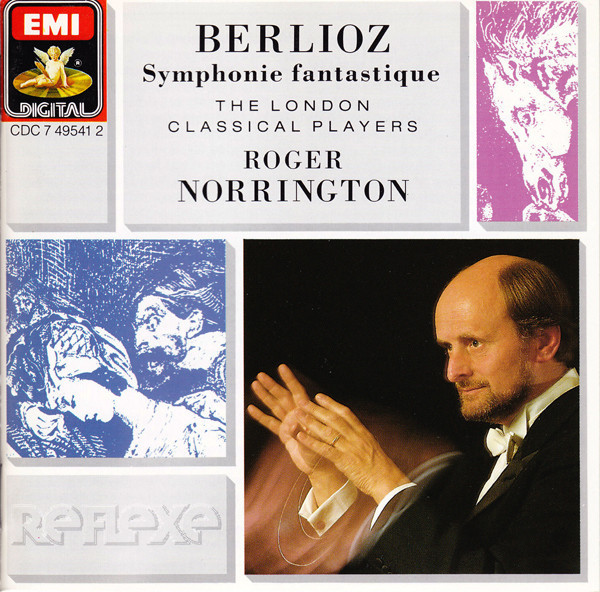

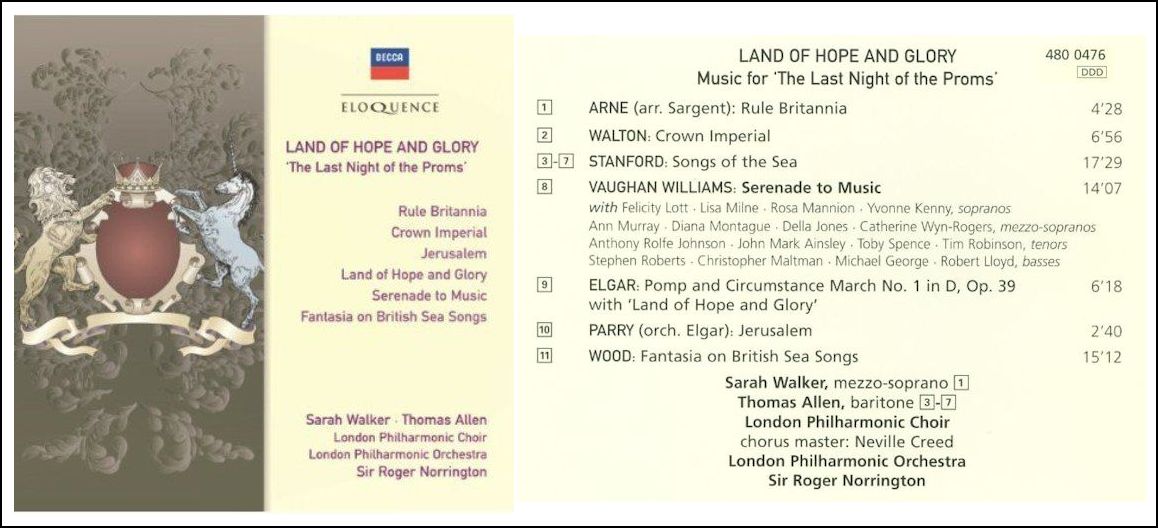

The London Classical Players leapt to worldwide fame with Norrington’s dramatic performances of Beethoven’s symphonies on period instruments. The recordings of these works for EMI won prizes in the UK, Belgium, Germany and the United States, and are some of the most sought-after readings of Beethoven Symphonies in our times. Many other recordings followed, not only of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven, but also of many 19th-century composers including Berlioz, Weber, Schubert, Schumann and Rossini. Norrington continues to push the boundaries of performance practice still further with groundbreaking recordings of Brahms’s four symphonies, and of works by composers including Wagner, Bruckner and Smetana. Norrington’s work on scores, orchestral sound and size, seating and playing style has had a growing effect on the perception of 18th- and 19th-century orchestral music. He is in great demand as a guest conductor for symphony orchestras worldwide, working regularly with orchestras in Berlin, Vienna, Leipzig, Salzburg, Amsterdam, Paris, New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles and London. He is Chief Conductor of the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra and of the Camerata Salzburg, and is closely associated with the Orchestra of the Age of the Enlightenment (which has taken over the work of the London Classical Players), and with the Philharmonia. Norrington also has wide experience as a conductor of opera. He was Music Director of the successful Kent Opera for fifteen years, conducting over 400 performances of 40 different works. He has worked as a guest conductor at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, at the English National Opera, at La Scala, La Fenice and the Maggio Musicale, and at the Wiener Staatsoper and the Salzburg Festival. He has recorded extensively for EMI, Virgin and Decca, made discs for Sony and BMG, and appears regularly on recordings for Hänssler Verlag with the Stuttgart Radio Orchestra. Norrington was knighted in June 1997 and is a Commander

of the Order of the British Empire, a Cavaliere of the Italian Republic,

Prince Consort of the Royal College of Music and Professor and Honorary

Member of the Royal Academy of Music, an Honorary Fellow of Clare College,

Cambridge, a Doctor of Music at the University of Kent and a Doctor

of the University of York.

== (Mostly) from the website of the Royal

College of Music, London

|

BD: Music is something you feel?

BD: Music is something you feel? RN: I quite like it, I must admit. Why not?

We sometimes try it as an experiment in our concerts in London. [Indeed,

at his concerts with the Chicago Symphony, he spoke to the audience

about this, and encouraged them to applaud after each movement. They

responded, timidly at first, but with greater enthusiasm as the concert

continued.] You can’t really expect it, though. Perhaps

it’s like resuscitating dead languages.

You can’t do that, but the thing about it I like is that the audience

gets a chance to participate. They have a role in concerts.

They aren’t just there to eavesdrop on some sacred rite. It’s

an enjoyable experience. We’re playing to the audience, for the

audience, to entertain them and to uplift them —

depending on the kind of music. They have a part to

play, and the more they can clap and laugh in funny bits, I’m very comfortable

with that.

RN: I quite like it, I must admit. Why not?

We sometimes try it as an experiment in our concerts in London. [Indeed,

at his concerts with the Chicago Symphony, he spoke to the audience

about this, and encouraged them to applaud after each movement. They

responded, timidly at first, but with greater enthusiasm as the concert

continued.] You can’t really expect it, though. Perhaps

it’s like resuscitating dead languages.

You can’t do that, but the thing about it I like is that the audience

gets a chance to participate. They have a role in concerts.

They aren’t just there to eavesdrop on some sacred rite. It’s

an enjoyable experience. We’re playing to the audience, for the

audience, to entertain them and to uplift them —

depending on the kind of music. They have a part to

play, and the more they can clap and laugh in funny bits, I’m very comfortable

with that.

Johann Joachim Quantz's On Playing Flute has long been recognized as one of the most significant and in-depth treatises on eighteenth-century musical thought, performance practice, and style. This classic text of Baroque music instruction goes far beyond an introduction to flute methods by offering a comprehensive program of studies that is equally applicable to other instruments and singers. The work is comprised of three interrelated essays that examine the education of the solo musician, the art of accompaniment, and forms and style. Quantz provides detailed treatment of a wide range of subjects, including phrasing, ornamentation, accent, intensity, tuning, cadenzas, the role of the concertmaster, stage deportment, and techniques for playing dance movements. Of special interest is a table that relates various tempos to the speed of the pulse, which will help today's musicians solve the challenge of playing authentic performance tempos in Baroque music. This edition includes 224 musical examples from Quantz's original text and features a new introduction by translator Edward R. Reilly that considers recent scholarship on Quantz's significant role in eighteenth-century musical activity. On Playing the Flute vividly conveys the constancy of musical life over time and remains a valuable guide for contemporary musicians. Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773), son of a blacksmith, enjoyed a long and successful career as a virtuoso soloist and orchestral performer on a variety of instruments. He was also a composer, an exceptional teacher and writer, and a flute maker. Tutor and Royal Prussian Chamber Musician to Frederick the Great, Quantz studied in Dresden and traveled throughout Europe to refine his musical skills and knowledge. Edward R. Reilly is Professor of Music, Emeritus, at Vassar College. He is the author of Quantz and His Versuch: Three Studies. == From the listing on Amazon.com

|

RN: [Laughs] Yes, perhaps

so. One would also be straight-jacketing the next generation by

telling them that that’s how Baroque and Classical and Romantic music

should be played. That’s their problem. Come on boys and

girls, you can do it!

RN: [Laughs] Yes, perhaps

so. One would also be straight-jacketing the next generation by

telling them that that’s how Baroque and Classical and Romantic music

should be played. That’s their problem. Come on boys and

girls, you can do it! RN: I was once, but what I’m

known for now is Nineteenth Century music — Haydn

to Brahms. In the ’60s I was known for

baroque music, yes.

RN: I was once, but what I’m

known for now is Nineteenth Century music — Haydn

to Brahms. In the ’60s I was known for

baroque music, yes. RN: Yes, absolutely. Exactly

the same, yes, and I try and make all recordings sound as if we’re

just playing them. We do lots of long takes. They aren’t

always all used, of course, and we may even do some inserts, but however

short the inserts, I go for a live sound, a live performance. That

is the way in which I work with all the record producers. I let

them look for the faults, so to speak, and I go for the performance.

So it’s like doing a concert. In rehearsals you’re looking for

faults, but in the concert you’re not looking for faults. The danger

with recordings is that you treat them like rehearsals. If I’m looking

for faults, then I’m not going to get that forward motion. I would

like our records to sound just absolutely bright and live, and some of

the best ones do.

RN: Yes, absolutely. Exactly

the same, yes, and I try and make all recordings sound as if we’re

just playing them. We do lots of long takes. They aren’t

always all used, of course, and we may even do some inserts, but however

short the inserts, I go for a live sound, a live performance. That

is the way in which I work with all the record producers. I let

them look for the faults, so to speak, and I go for the performance.

So it’s like doing a concert. In rehearsals you’re looking for

faults, but in the concert you’re not looking for faults. The danger

with recordings is that you treat them like rehearsals. If I’m looking

for faults, then I’m not going to get that forward motion. I would

like our records to sound just absolutely bright and live, and some of

the best ones do. RN: The way it actually comes out will be slightly

different. The concept will be of the kind of grace and gesture

that this piece has, or the life that it has. That may change over

time, but I don’t try and do stamped-out performances that are precisely

the same. No, I’m not one of those, particularly when you get to

the later repertory. When you’re doing Brahms, for instance, you

can’t do two performances the same. A Beethoven symphony you can

do the same if you want to, but you will change, of course, if you’re

creative. But Brahms, by definition, is just in a different world,

like Wagner or Bruckner. There are going to be changes because

it’s that kind of changeable animal. The difficulty in Brahms, in

fact, becomes when you record. If you’ve just been in tour and you’ve

done seven performances, which shall we put on disc

— one? Three? Six?

RN: The way it actually comes out will be slightly

different. The concept will be of the kind of grace and gesture

that this piece has, or the life that it has. That may change over

time, but I don’t try and do stamped-out performances that are precisely

the same. No, I’m not one of those, particularly when you get to

the later repertory. When you’re doing Brahms, for instance, you

can’t do two performances the same. A Beethoven symphony you can

do the same if you want to, but you will change, of course, if you’re

creative. But Brahms, by definition, is just in a different world,

like Wagner or Bruckner. There are going to be changes because

it’s that kind of changeable animal. The difficulty in Brahms, in

fact, becomes when you record. If you’ve just been in tour and you’ve

done seven performances, which shall we put on disc

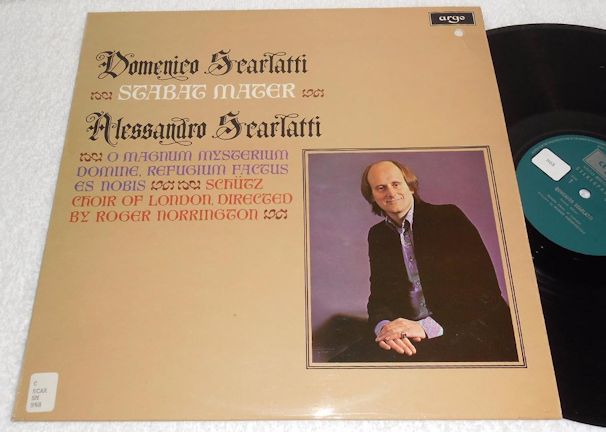

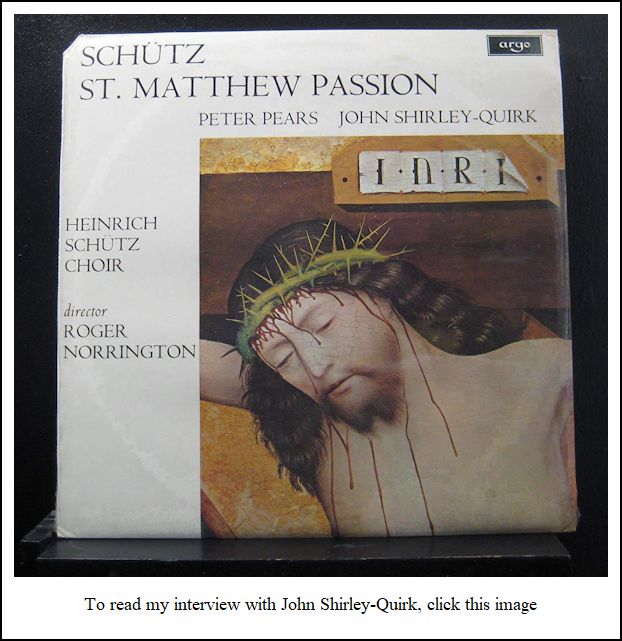

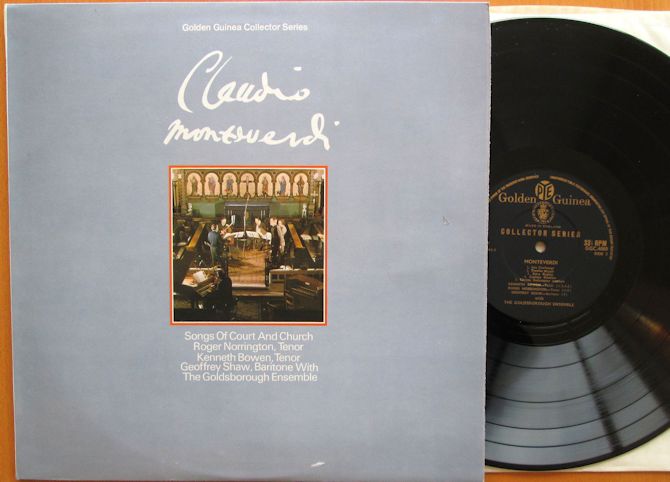

— one? Three? Six? RN: A couple. Some Schütz

and Monteverdi. They were on Pye Golden Guinea, and were made

in the ’60s. I was a very keen, very able

singer. I sang the Matthew Passion as the Evangelist in

the Festival Hall, and Ferrando in Così Fan Tutte for Yehudi Menuhin, and

all sorts of stuff. I was very busy, pretty well a full-time professional

solo tenor. So, it gave me a very good feel for singing when I

started, having given up the violin before that. I gave up singing

eventually and stayed just with the conducting, but I was always at home

with singers. It was easy to work with choirs, and it was easy encourage

professional singers to do that little bit extra, or to do it slightly

differently. They felt fairly at home with me.

RN: A couple. Some Schütz

and Monteverdi. They were on Pye Golden Guinea, and were made

in the ’60s. I was a very keen, very able

singer. I sang the Matthew Passion as the Evangelist in

the Festival Hall, and Ferrando in Così Fan Tutte for Yehudi Menuhin, and

all sorts of stuff. I was very busy, pretty well a full-time professional

solo tenor. So, it gave me a very good feel for singing when I

started, having given up the violin before that. I gave up singing

eventually and stayed just with the conducting, but I was always at home

with singers. It was easy to work with choirs, and it was easy encourage

professional singers to do that little bit extra, or to do it slightly

differently. They felt fairly at home with me. BD: Does the sick music die off?

BD: Does the sick music die off?

========

========

========

-- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

======== ========

========

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 26, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.