|

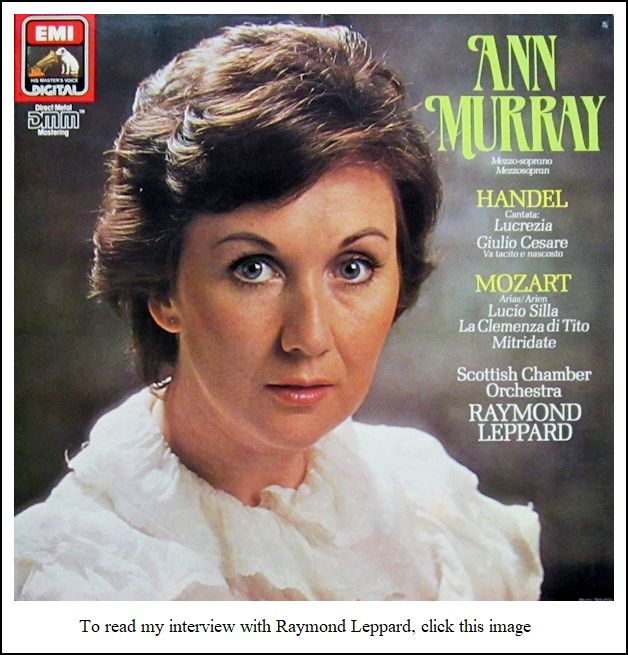

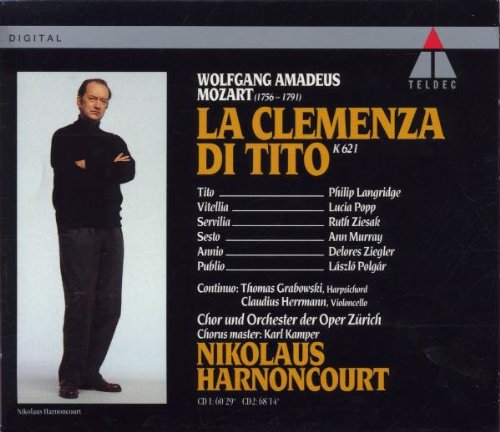

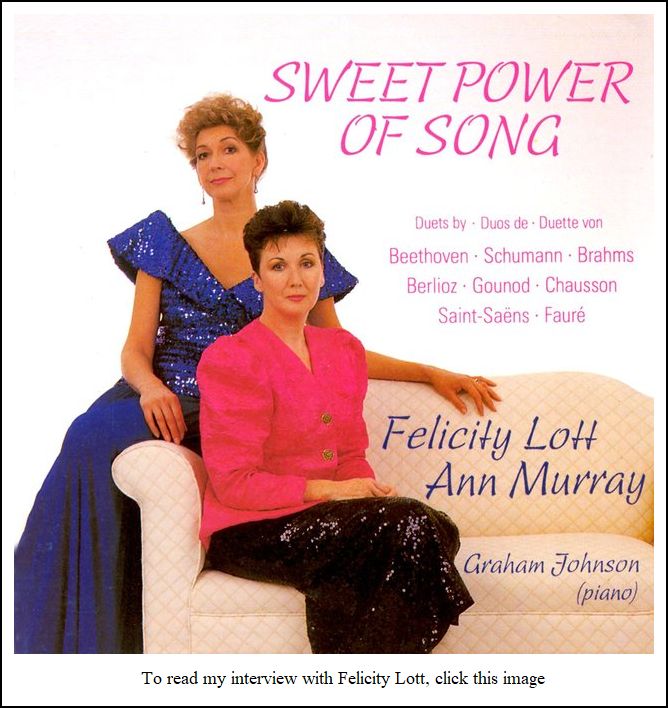

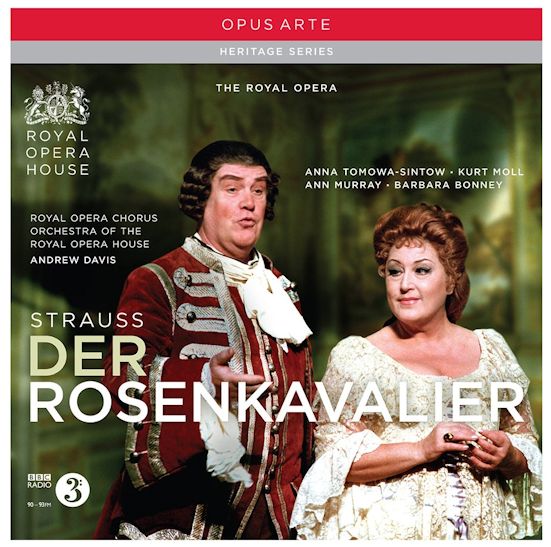

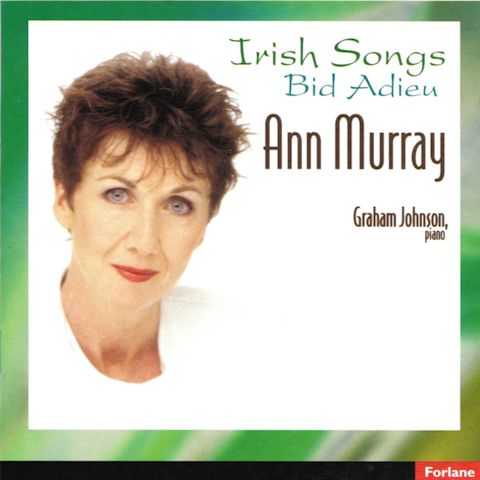

Mezzo-Soprano Ann Murray was born August 27, 1949, in Dublin. Having won a number of prizes at the Feis Ceoil, she studied singing at the College of Music (now the DIT Conservatory of Music and Drama, Dublin) with Nancy Calthorpe, as well as arts and music at University College Dublin. In 1968, she made her Irish opera debut performing the shepherd role in a concert performance of Tosca. She pursued further studies with Frederic Cox at the Royal Manchester College of Music and made her stage debut as Alcestis in Christoph Willibald Gluck's Alceste in 1974. She has since sung at all major opera houses and is particularly noted for her performances in works by George Frideric Handel, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Richard Strauss. Murray performs mainly at Covent Garden, the English National Opera, and the Bavarian State Opera (where she was made Kammersängerin in 1998). In 2012, she was made an Honorary Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the Diamond Jubilee Honours for her services to music. She has received an honorary doctorate in music from the National University of Ireland in 1997, and the Bavarian Order of Merit in 2004. She maintains her links with Ireland and is a patron of the Young Associate Artists Programme of Dublin's Opera Theatre Company. In September 2010, she was appointed professor of singing at the Royal Academy of Music in London, where she was previously (since 1999) an honorary fellow. |

AM: That I don’t know. That’s

also a difficult one. I try to portray the character, but all

these characters that one portrays have elements of one’s own personality.

It is either in the piece, or you bring that to the piece, so it’s

intermingled or intertwined. I really couldn’t say which becomes

which.

AM: That I don’t know. That’s

also a difficult one. I try to portray the character, but all

these characters that one portrays have elements of one’s own personality.

It is either in the piece, or you bring that to the piece, so it’s

intermingled or intertwined. I really couldn’t say which becomes

which. BD: We do have really good acoustics,

here.

BD: We do have really good acoustics,

here. AM: Yes, that also happens quite a lot.

You think, “Gosh, I didn’t get that feeling.

I wasn’t as highly strung. I wasn’t as tense. I wasn’t

as concentrated this evening,”

and then you hear from people that it was even better than the dress

rehearsal.

AM: Yes, that also happens quite a lot.

You think, “Gosh, I didn’t get that feeling.

I wasn’t as highly strung. I wasn’t as tense. I wasn’t

as concentrated this evening,”

and then you hear from people that it was even better than the dress

rehearsal.

Isabella Angela Colbran (2 February 1785 – 7 October 1845) was a Spanish opera singer known in her native country as Isabel Colbrandt . Many sources note her as a dramatic coloratura soprano but some believe that she was a mezzo-soprano with a high extension, a soprano sfogato. She collaborated with opera composer Gioachino Rossini in the creation of a number of roles that remain in the repertory to this day. They were married on 22 March 1822. All his life Rossini credited Colbran as being the greatest interpreter of his music. Descriptions of Colbran's voice characterise the timbre as "sweet, mellow" with a rich middle register. Rossini's music for her suggests perfect mastery of trills, half-trills, staccato, legato, ascending and descending scales, and octave leaps. Her vocal range extended from F-sharp below the staff to E above, with a high F sometimes available. |

BD: I wonder if he would have calmed down at all.

BD: I wonder if he would have calmed down at all. BD: Do they have them at Covent Garden?

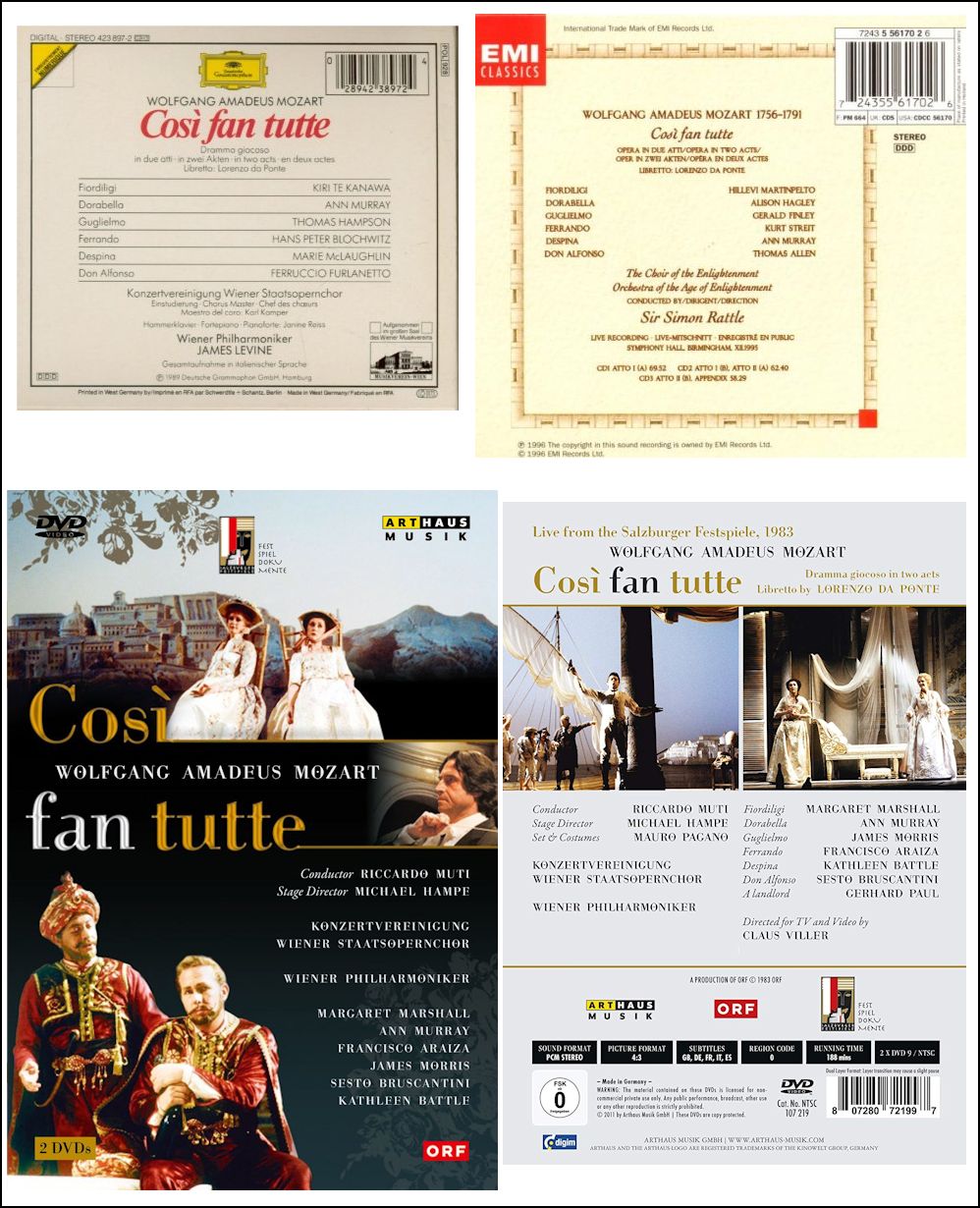

BD: Do they have them at Covent Garden? BD: You’ve made some recordings. Do you

sing differently for the microphone than you do for the live audience?

BD: You’ve made some recordings. Do you

sing differently for the microphone than you do for the live audience?

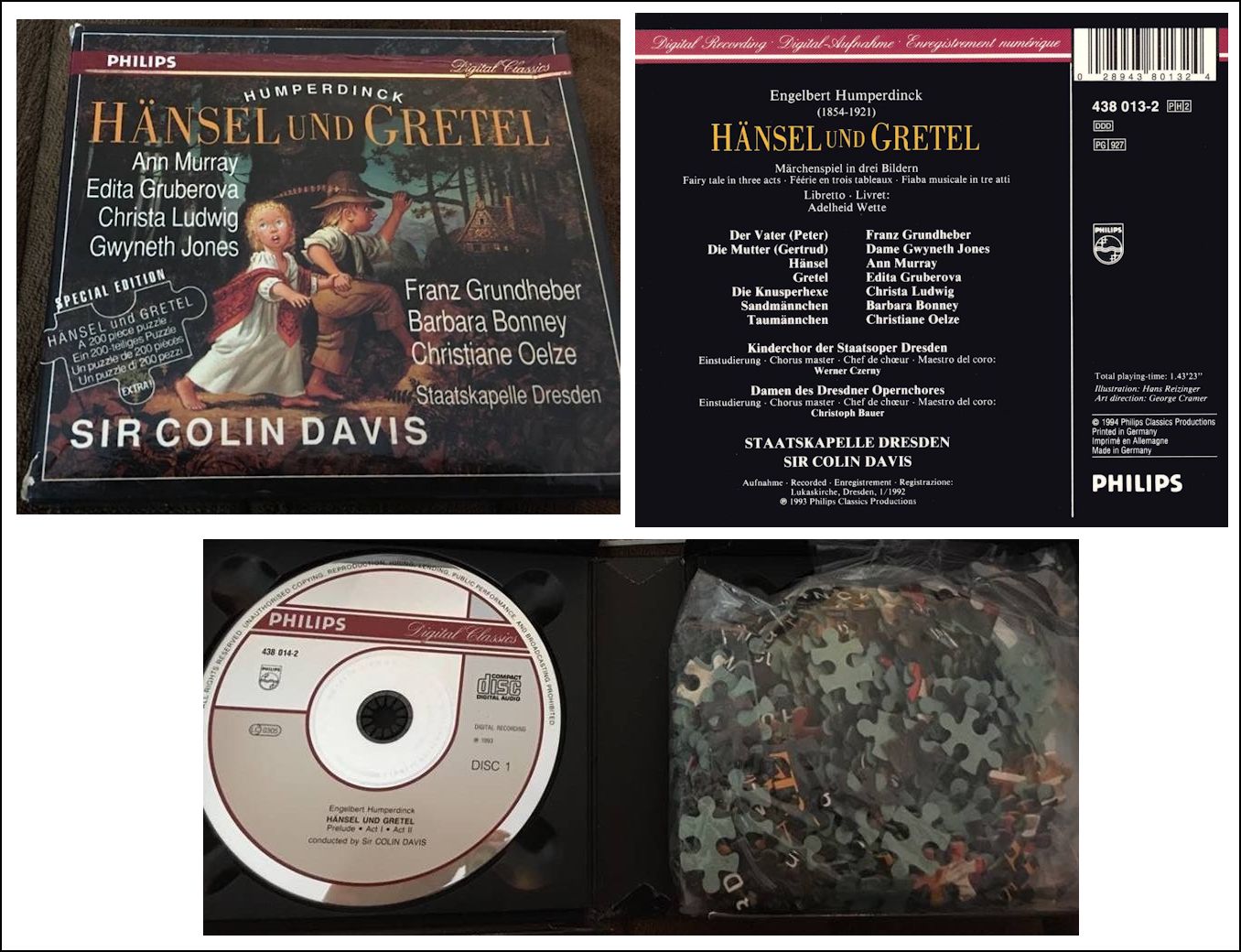

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So

it took you the length of the opera to put the puzzle together?

BD: [With a gentle nudge] So

it took you the length of the opera to put the puzzle together?

BD: Is singing fun?

BD: Is singing fun? AM: There’s a responsibility to bring

music and the arts in general to young people. We take out son

from time to time to art galleries. He’s only little, but he

has his opinions. He thinks some things are dreadful, and some

other things are very beautiful. He loves music. He goes

to the opera a lot when he’s not at school. He loves orchestral

music. Yes, I think it’s very important. His absolute hero

at this moment is Wynton Marsalis. He thinks he’s never heard anything

like it, so he started the trumpet the day before yesterday because he

saw Wynton Marsalis’s masterclass being broadcast from Tanglewood.

He was just so taken with this man’s musical personality that he said he

would love to learn the trumpet. So, he started.

AM: There’s a responsibility to bring

music and the arts in general to young people. We take out son

from time to time to art galleries. He’s only little, but he

has his opinions. He thinks some things are dreadful, and some

other things are very beautiful. He loves music. He goes

to the opera a lot when he’s not at school. He loves orchestral

music. Yes, I think it’s very important. His absolute hero

at this moment is Wynton Marsalis. He thinks he’s never heard anything

like it, so he started the trumpet the day before yesterday because he

saw Wynton Marsalis’s masterclass being broadcast from Tanglewood.

He was just so taken with this man’s musical personality that he said he

would love to learn the trumpet. So, he started.© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 15, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three months later, and again in 1997 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.