Composer Juli Nunlist

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

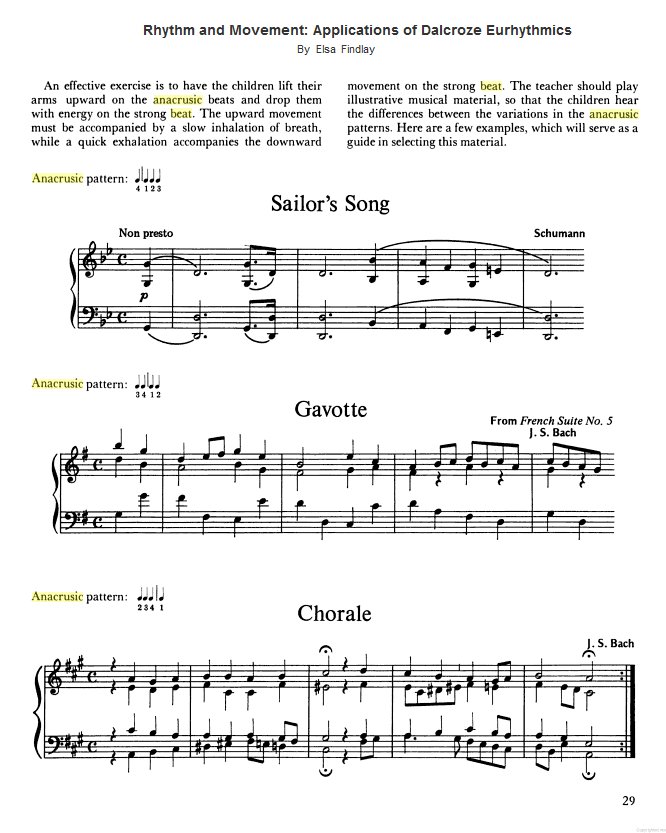

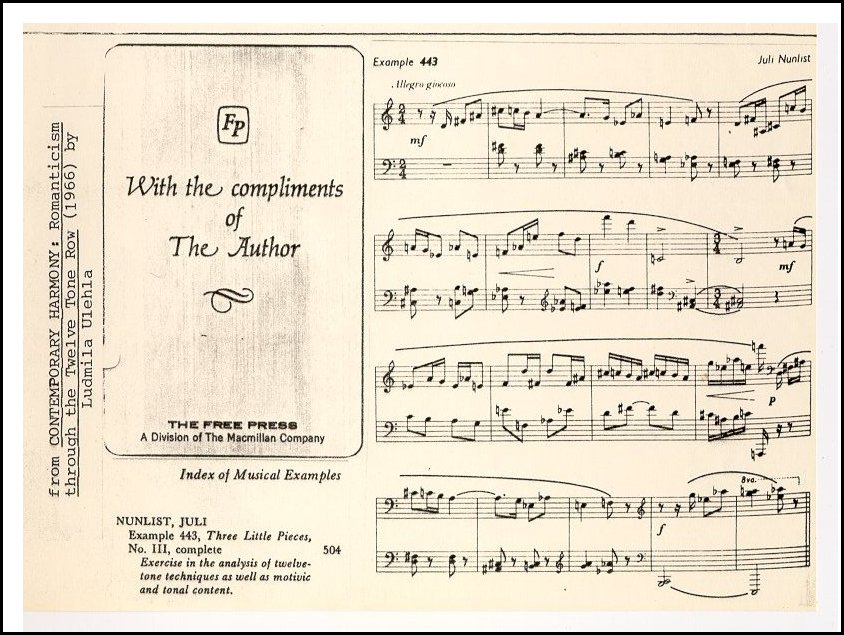

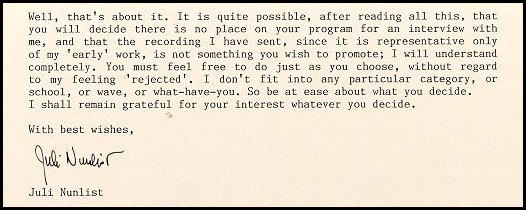

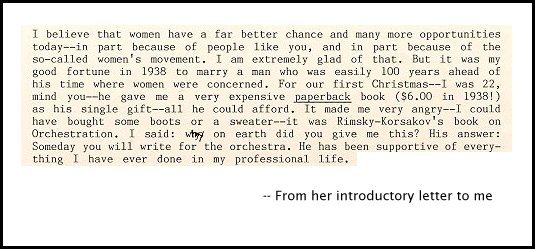

In the summer of 1987 when I first wrote to Juli Nunlist about doing an

interview for the radio, she responded with a detailed four-page letter

and a few xeroxes of other items related to her career as a

composer. One of those extras is shown above.

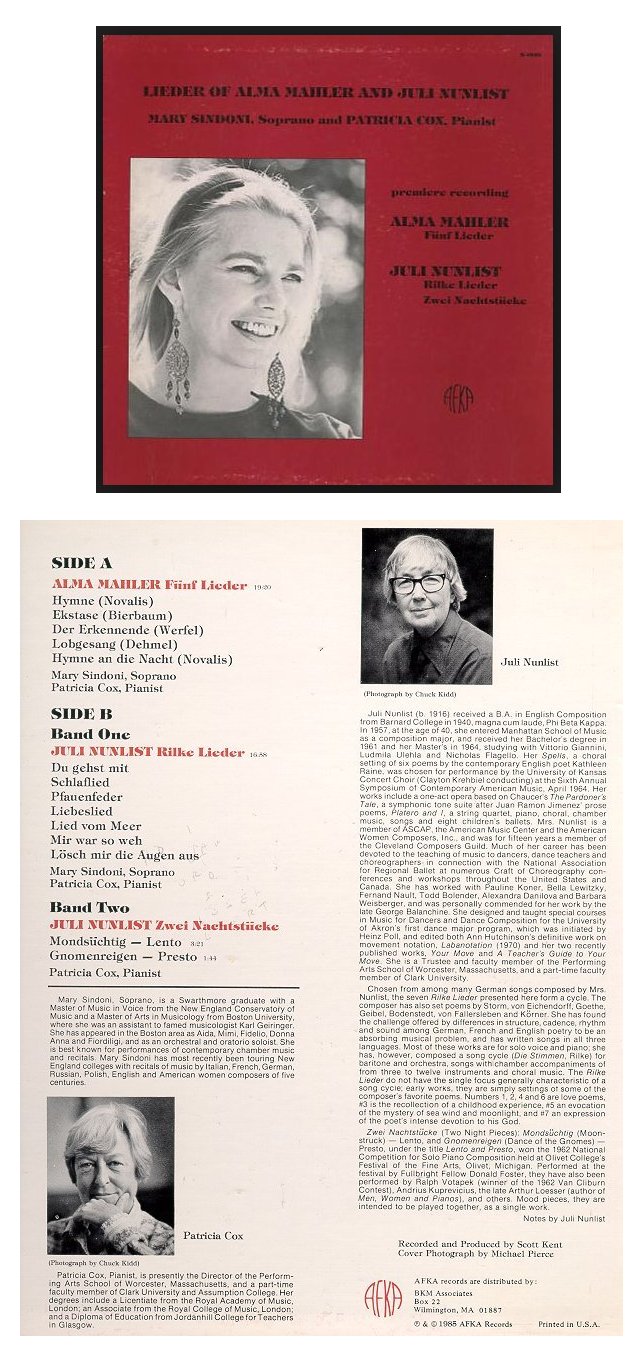

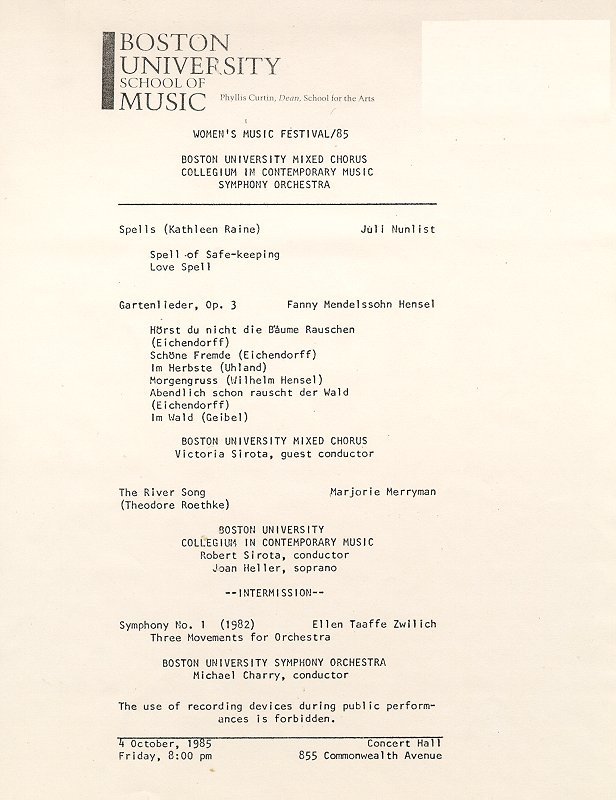

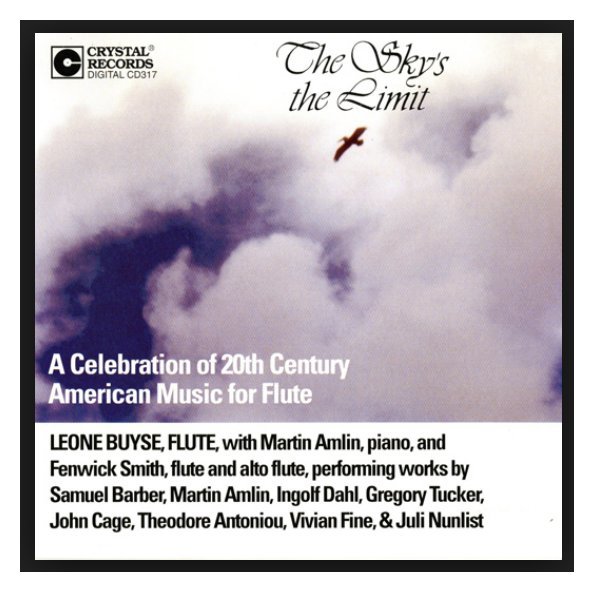

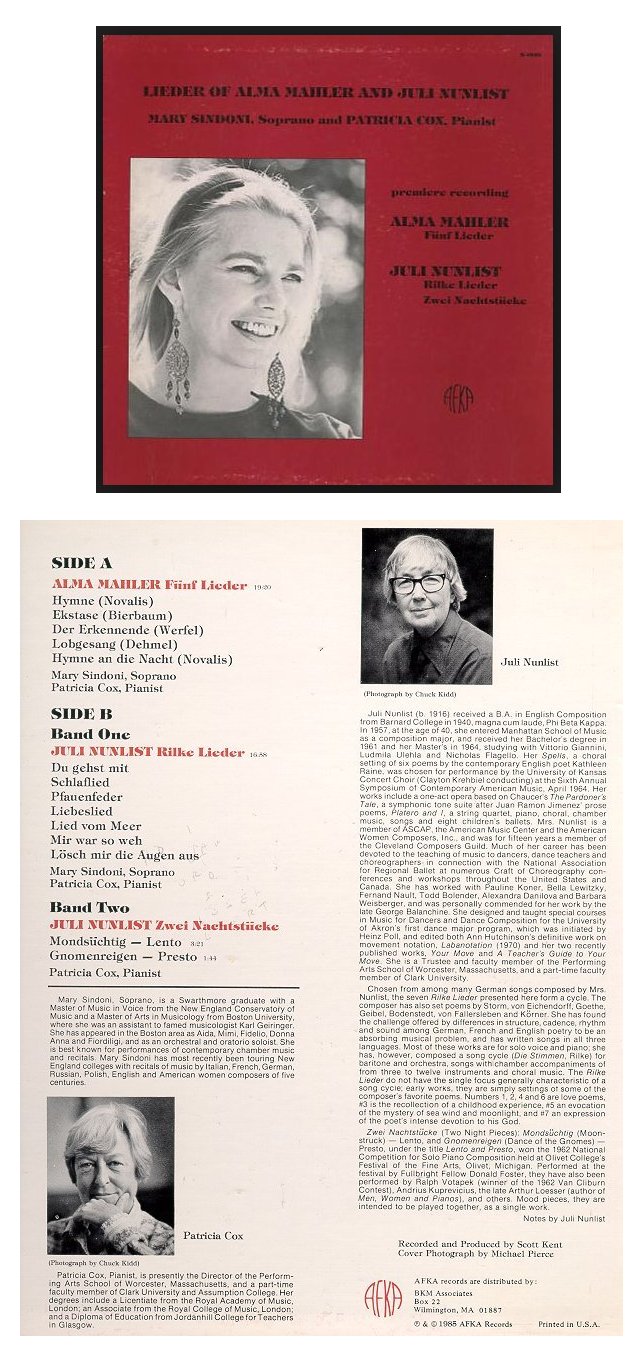

She also sent one of her recordings, indeed the only one which she

wished to be used on the air. There were a couple of other items

on vinyl at that time, but she explained why those were unworthy, and I

respected her wishes and did not use them. The LP she did send

was quite nice, and the biographical material from the back of the

jacket is reproduced below.

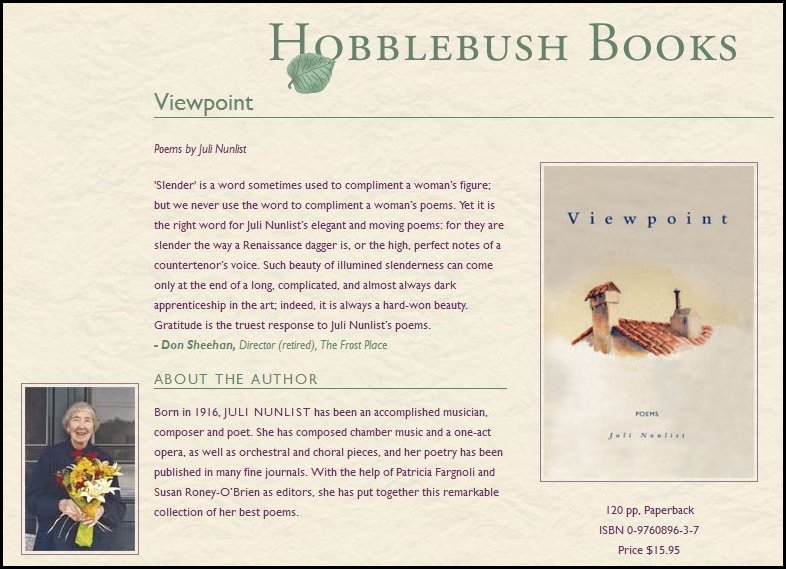

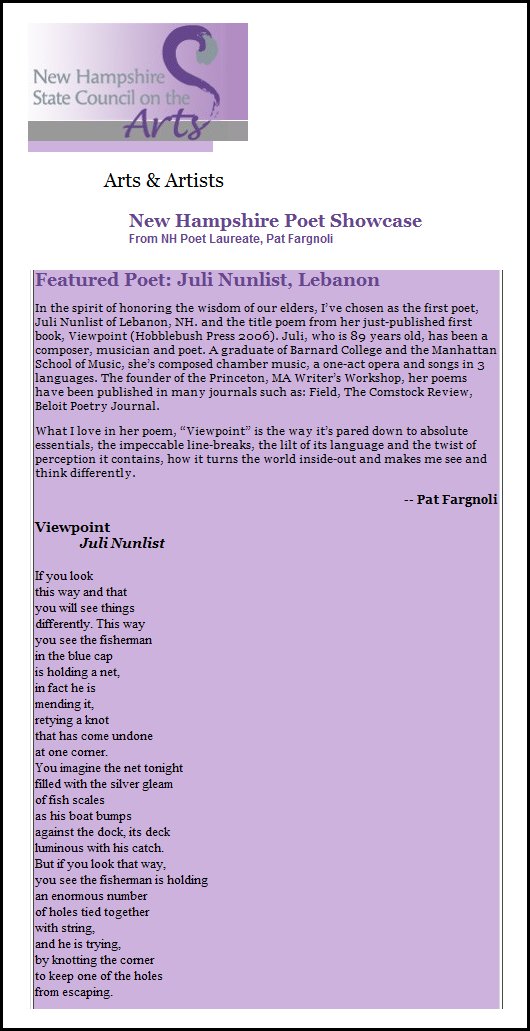

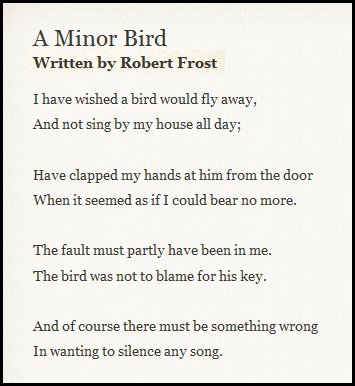

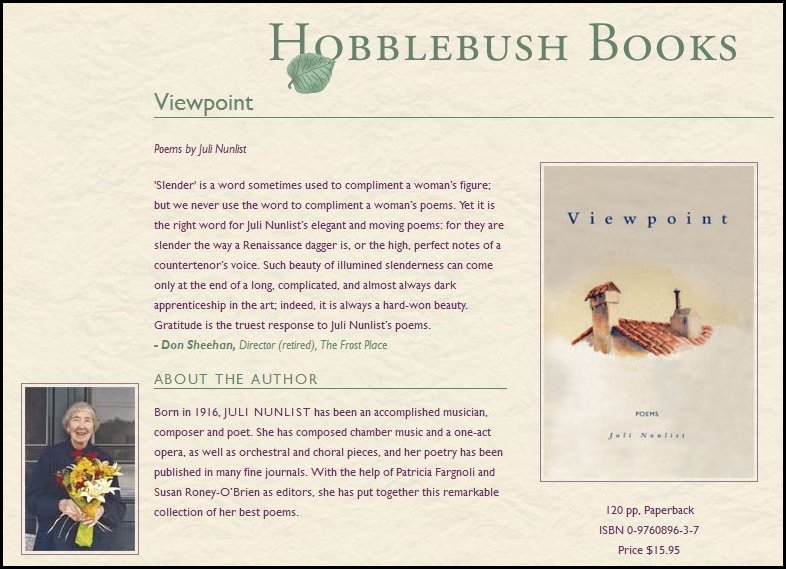

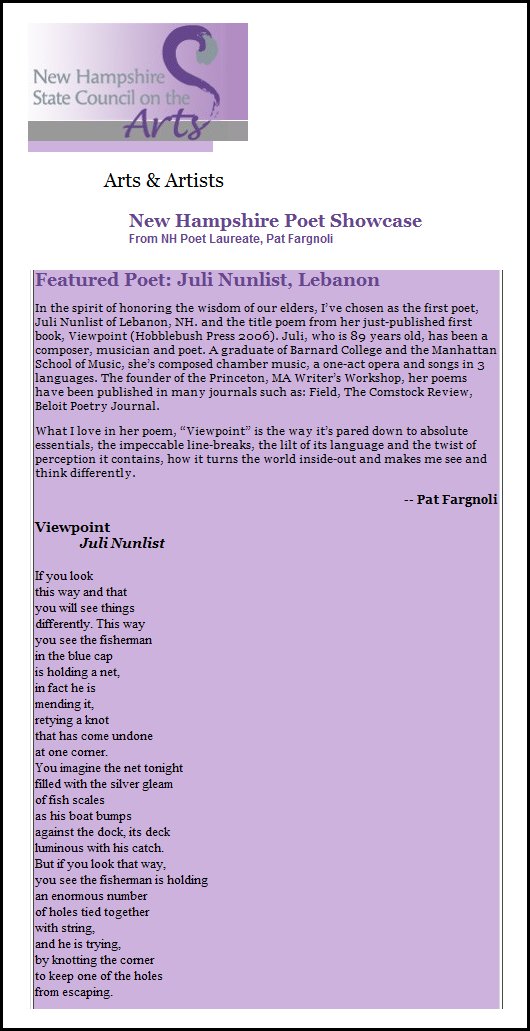

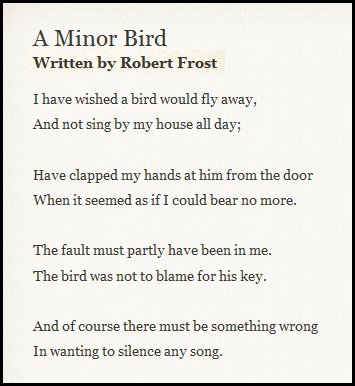

Besides her musical compositions, she is also a published poet, as can

be seen here . . . . .

She also spent a great deal of time with dancers. This balletic

endeavor included the daunting task of trying to bridge the gap of

understanding between the musicians who were offstage or in the pit and

those performers on the stage.

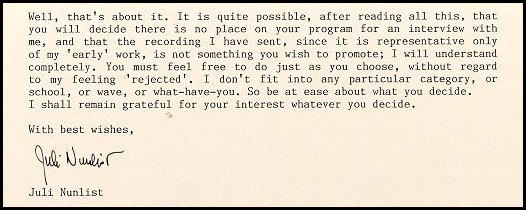

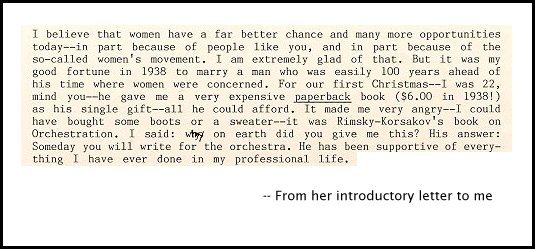

Even though she seemed pleased to have heard from me, several times she

was self-deprecating both in our conversation (most of which I have

omitted from the text) and in the last paragraph of that letter . . .

Needless to say, I followed through and made the phone call for the

interview, and our conversation is contained on this page.

Much of what she told me in the letter was discussed during the call,

but one further item of particular interest was left unsaid, and has

been added at the appropriate place in the text below.

She mentions a few other composers, and those whose names are links

refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. She also

reminded me that she was, at that time, nearly 71 years old.

Here is what was said in 1987 . . . . . . .

Bruce Duffie:

You started out playing piano, then

abandoned

it, and then you came back to it. What,

specifically, kept you involved with music in between the times when

you were studying it?

Juli Nunlist:

My mother’s family was very

musical. She and her brothers were both naturally gifted, and

without having studied, played the piano very well. Therefore we

had a piano in our home which my mother played, and that was how I got

started taking piano lessons. I stopped because they made me be

in a

recital, but I didn’t stop playing around with it. I played for

many years off and on, mostly at my own things, messing about and

composing songs and little piano pieces and so

on. Eventually, through meeting with Barbara Weisberger, and the

fact

that my daughter began to study ballet with her, I became interested in

ballet and dance, and eventually ended up composing eight children’s

ballets for the Wilkes Barre Ballet Theater, of which Barbara was the

director. A friend of our family saw the last

one that I did, and suggested that I should study music, and

that’s how that got started.

BD: How are

the pieces that you wrote before you

began to study music formally different from the pieces that you are

writing today?

JN: Of course, in

the beginning they were quite

simple, although my husband’s step-mother was a musician. She was

a graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory,

and she heard me doodling at a little contrapuntal piece one day in

their home. She asked what it was and I told her it was a piece

that I wrote, and she said, “You really

should study music.” This was before I was even married. I

wrote songs in German and English, not in French

until later, but I wouldn’t change some of them now. Some

of them I would, of course, but for what they were I was pleased.

They were

those of a one-handed pianist, in a way, because I wasn’t a very good

pianist, and the right hand did a lot more than the left hand. I

had to learn a lot about that when I

started studying music. When I started studying

the piano seriously, which was about a year and a half before I went to

Manhattan School, David Jatovsky was my piano teacher. He was a

great musician and a great teacher, and I learned an immense amount

from him. Knowing that I mainly wanted

to compose, he taught me not only how a piano should be

played and how it should sound, but that it was in itself an

orchestra. That is, it had all the range of the orchestral

instruments. I was shown how to use that because I always

composed at the piano, and he showed me how to use it not as a pianist,

but as a person thinking in terms of chamber music, orchestration and

things like that, and I’m very grateful to him for that.

JN: Of course, in

the beginning they were quite

simple, although my husband’s step-mother was a musician. She was

a graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory,

and she heard me doodling at a little contrapuntal piece one day in

their home. She asked what it was and I told her it was a piece

that I wrote, and she said, “You really

should study music.” This was before I was even married. I

wrote songs in German and English, not in French

until later, but I wouldn’t change some of them now. Some

of them I would, of course, but for what they were I was pleased.

They were

those of a one-handed pianist, in a way, because I wasn’t a very good

pianist, and the right hand did a lot more than the left hand. I

had to learn a lot about that when I

started studying music. When I started studying

the piano seriously, which was about a year and a half before I went to

Manhattan School, David Jatovsky was my piano teacher. He was a

great musician and a great teacher, and I learned an immense amount

from him. Knowing that I mainly wanted

to compose, he taught me not only how a piano should be

played and how it should sound, but that it was in itself an

orchestra. That is, it had all the range of the orchestral

instruments. I was shown how to use that because I always

composed at the piano, and he showed me how to use it not as a pianist,

but as a person thinking in terms of chamber music, orchestration and

things like that, and I’m very grateful to him for that.

BD: He had

the foresight to use what talent and

abilities you had, rather than just forcing performance on you?

JN:

Yes. Yes, indeed. I was able to play

much better than I thought I ever would at the time, but his main idea

was to help me become a better composer through understanding what the

piano had to offer.

BD: So then

you always had faith in your

own ideas?

JN: Yes, and

I still do. The music I write now

is very

different from the music you have on the record. The first six of

those

songs were written in the year that I was being prepared by David and

his son, Steven J, to go to Manhattan. The seventh one was

written after I’d been in school several years, and I

wouldn’t change them. I’m very fond of them still, but the

music I write now has moved. There are no keys

anymore, but it’s not atonal. Everything is in a tonal area, very

melodic, really romantic, but it’s not at all like the music I wrote

before

I went to school. It’s more complex. It has much more

dissonance in it, although it’s not far out at all. It’s very

conservative.

BD: You don’t

reject the idea of far out music,

though?

JN: Not at

all. I use it in teaching the

choreographers and dancers, and dance teachers.

I’ve used all kinds of music — electronic

music, far out music, minimalist music, whatever you want

— you name it. I’ve tried

to use as broad a spectrum as I can. I have used everything from

Gregorian chant and 12th Century Spanish music to, well,

everything. It’s best for the choreographers

to be exposed to as wide a spectrum as possible.

BD: Where, if

any place, do you actually draw

the line between music and just sound?

JN: Oh,

that’s a tough question. I’m not sure

I’d like to be forced to draw that line, because one

reaches a place and time in life when it is perhaps not possible to

hear. The best way I can explain that to you is by telling you a

story of a very dear friend of ours, an elderly New England

lady named Wheeler who was a very fine violist and violinist. I

met her through

my participation in the Performing Arts School of Worcester. She

was a sponsor of that school and was very generous to it. At one

time I

had a program of all my music done at the school, and it

consisted of the two piano pieces that you have on the record, and the

Seven Songs, and my string quartet. I asked Miss

Wheeler

please to come to the concert. I told her that she might not mind

the two piano pieces, that she would love the songs, and that she would

hate the string quartet. [Both laugh] She was a doll.

She came, and when the

concert was over she came up to me and she said, “You were absolutely

right, Juli. I didn’t mind the piano pieces. I loved

the songs and I couldn’t hear the string quartet.” She didn’t use

the word “hate.” She simply said, “I couldn’t hear the string

quartet.” This is the way I feel, that perhaps I have

reached a place where I can’t hear this music. I have a marvelous

book, The Lexicon of Musical

Invective.

BD: Oh sure,

by Nicolas

Slonimsky.

[The book is a collection of negative

criticism of works by famous composers now regarded as standard

repertoire.]

JN:

Yes! Well, those people couldn’t hear that

music, I’m sure of that. Otherwise they wouldn’t have said

the things they said! And I have the feeling that I cannot hear

much of the far out music. I’ve talked to Ronald Perera

about this. He’s head of electronic music and a professor at

Smith, and a marvelous person, a marvelous teacher and a very fine

composer. I acknowledge that there are some marvelous sounds

that can be made that are not playable on ordinary instruments, and I

hear them. Some of them are used on TV in the National

Geographic things and so on, and they are beautiful, but I’m old

enough, maybe, or so old that I like music that can

actually be played on a real instrument. I had a talk with Otto Luening a good

many years ago about that.

He came to Cleveland when I was there with Babbitt, and Rzewski. There

was a flute

suite, with flute sounds electronically modified, and it was a lovely

thing. It was delightful and charming! I loved it, and I

argued with him later that if I were a flutist I couldn’t go to the

store and buy it and go home and play it. It had to be canned,

and that troubles me, frankly. I want human

beings to be able to play music on whatever kind of instrument, but not

just have

to listen to something that’s a machine.

BD: Let me

probe this just a little bit

further, then. What do you feel is the ultimate purpose of music

in society?

JN: It’s

along with the arts, all the

arts. They are the core of education to me, and they are the most

needed and most valued thing that any society can have. Without

them the society is lost, as far as I’m concerned, and that’s not just

music. It’s all art. It’s the old Greek thing.

They are the core of all education, and there is certainly going to be

experimentation in all areas of art. I remember Mr. Giannini

saying once that there’s an immense spectrum in any era of music.

He

was talking then, of course, about music, but it goes for any

art — painting, poetry, dance, whatever. There’s going to be a

fringe on either end of that spectrum that’s going to fall away and

wither and perhaps just be lost, but there’s a main, broad part of it

that’s going to continue living century after century because people’s

ears will be opened and they’ll begin to hear new things and yet not

discard the old ones. It has a great virtue, a great moral

value, a great educational value. I don’t think anyone is

complete who hasn’t been exposed to some art and had the chance to try

to develop it. I believe everyone has the seed of creativity in

him or her. I don’t mean they all

can be great artists, but if it’s

properly nurtured they all can

understand creating art and

take a part in it and be better people for it. It’s a

marvelous discipline. I don’t know that I can say any

more.

BD: Let me

pursue a different track of this same

idea. Where do you feel is the balance between the

artistic achievement and the entertainment value, either in music or in

any of the arts?

JN: They both

have their place, of

course. When you say entertainment, what do you mean?

BD: Well, do

you differentiate between art and

entertainment?

JN: Oh yes, I think

so. Maybe it’s a

gray area. I have Aaron

Copland’s book, What to Listen for

in Music. I use that in teaching, and it’s the history of

levels of musical consciousness. First, the sensuous one where I

tell my

students, “You all do your homework or other chores to music you

like. It’s entertaining and you love it, but you don’t even hear

it. You’re doing your homework, but you’re in this bath of

sound, and then suddenly you hear a piece that you love.

It’s your favorite, and you drop your homework and you listen.

You’re entertained. Then when that piece stops and the rest

goes on, you go back to your homework.” The second level, as he

says, is the level where you see the

children playing, or the rainy day, or the funeral procession.

I’ve forgotten what he terms it, but then the last

level is the musical level, and that’s the level where you move into

art. Everyone can be entertained at some time by listening to a

piece he loves, but it’s not the same thing as deliberately composing

it or listening to a Mozart symphony. I’m not sure that there’s

a line I can draw. I am, if you wish to use the word, entertained

when I listen to great music. I don’t know whether it’s the use

of the word that troubles me or not. I am moved and uplifted, and

if you wish, entertained. I have a youngster now

who wants to “learn to play the piano.” I’m not a piano

teacher. She works for me a little and she wants me to show her

how to play the piano. She starts out with the theme song of The Pink Panther because her father

likes it. She brings me that music, which she has

borrowed from a girlfriend, and I say, “Fine, we will

start, and you will learn how to play the theme song to The Pink

Panther.” Through music that is entertaining to her I hope

to draw her into music

that will mean more to her. One of the reasons I stopped taking

lessons myself when I was seven or eight was that I was studying the

recital pieces which were The March

of the Dwarfs and The

Norwegian Dance by Grieg. They were very difficult pieces

for a

seven year old, and I don’t know how I played them. They must

have sounded terrible! But the reason I stopped wasn’t only the

recital; it was because I was in love with Vagabond King,

which was just new when I was seven, and I wanted to learn to play some

of the music

from it. But my teacher wouldn’t hear of it. She was so

rigid! She said, “I won’t help you with any of that,” and I

said, “Then I won’t work with you on any of the

others.” I think she made a mistake, but I’m not sorry she

made it, because I think she was a very bad piano teacher! [Both

laugh] But I don’t think it’s a good idea to look down

on something that is entertaining. I was in an Operetta Club in

Montclair when I was in high school, and we did all the D’Oyly Carte

operettas

and we did Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml and you name it. I

was happy as a clam and I loved doing it, and it brought me a

lot closer to music.

JN: Oh yes, I think

so. Maybe it’s a

gray area. I have Aaron

Copland’s book, What to Listen for

in Music. I use that in teaching, and it’s the history of

levels of musical consciousness. First, the sensuous one where I

tell my

students, “You all do your homework or other chores to music you

like. It’s entertaining and you love it, but you don’t even hear

it. You’re doing your homework, but you’re in this bath of

sound, and then suddenly you hear a piece that you love.

It’s your favorite, and you drop your homework and you listen.

You’re entertained. Then when that piece stops and the rest

goes on, you go back to your homework.” The second level, as he

says, is the level where you see the

children playing, or the rainy day, or the funeral procession.

I’ve forgotten what he terms it, but then the last

level is the musical level, and that’s the level where you move into

art. Everyone can be entertained at some time by listening to a

piece he loves, but it’s not the same thing as deliberately composing

it or listening to a Mozart symphony. I’m not sure that there’s

a line I can draw. I am, if you wish to use the word, entertained

when I listen to great music. I don’t know whether it’s the use

of the word that troubles me or not. I am moved and uplifted, and

if you wish, entertained. I have a youngster now

who wants to “learn to play the piano.” I’m not a piano

teacher. She works for me a little and she wants me to show her

how to play the piano. She starts out with the theme song of The Pink Panther because her father

likes it. She brings me that music, which she has

borrowed from a girlfriend, and I say, “Fine, we will

start, and you will learn how to play the theme song to The Pink

Panther.” Through music that is entertaining to her I hope

to draw her into music

that will mean more to her. One of the reasons I stopped taking

lessons myself when I was seven or eight was that I was studying the

recital pieces which were The March

of the Dwarfs and The

Norwegian Dance by Grieg. They were very difficult pieces

for a

seven year old, and I don’t know how I played them. They must

have sounded terrible! But the reason I stopped wasn’t only the

recital; it was because I was in love with Vagabond King,

which was just new when I was seven, and I wanted to learn to play some

of the music

from it. But my teacher wouldn’t hear of it. She was so

rigid! She said, “I won’t help you with any of that,” and I

said, “Then I won’t work with you on any of the

others.” I think she made a mistake, but I’m not sorry she

made it, because I think she was a very bad piano teacher! [Both

laugh] But I don’t think it’s a good idea to look down

on something that is entertaining. I was in an Operetta Club in

Montclair when I was in high school, and we did all the D’Oyly Carte

operettas

and we did Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml and you name it. I

was happy as a clam and I loved doing it, and it brought me a

lot closer to music.

BD: Did

you

sing in the

chorus or play in the orchestra?

JN: I sang in

the chorus. My two best friends

in high school, both girls, were also in it with me, and one of them

was

very good. She was an understudy sometimes when I was simply in

the chorus. I never got beyond the chorus, but I had a marvelous

time! I sang and sang and sang, and I know it helped bring me

closer to music. It was more than sheer

entertainment. It was just glorious! I love those old songs

now. They mean a great deal to me and also to my mother before

she died. We used to go to every Jeannette McDonald and Nelson

Eddy movie

there was when she was in her eighties, so she could hear those old

songs again. I can’t hear, for example, rock music. It

doesn’t mean a

thing to me. In the first place, I get deaf if I even start to

listen to it. But my youngster

goes to every concert at the Centrum in Worcester. I ask her how

she can stand the noise and she says, “You get used to

it.” I say, “It’s going to hurt your hearing,” and she just

shrugs. But that, to me, is not music. But it is to a lot

of

people, and who am I to say?

BD: For you,

what constitutes

greatness in music?

JN: Bach,

Brahms, and Beethoven, for

example.

BD: What did

they have or what did they do that

others lacked?

JN: How can I

say? If I knew that, maybe I

could do it myself! They speak a language

that is special. It’s like Rembrandt and Shakespeare and

Leonardo.

Who can explain what they did or what they had? I’ve never

tried. I’ve never thought about it that way. I love certain

poets

— for example,

contemporary poets

— and I’m trying to write poetry all the time.

Because I couldn’t write the way

they did or as well as they did, if that made me not write poetry then

there’s

something wrong. I know I’ll never be a Bach or a

Beethoven or a Brahms or a Stravinsky or a Bartók, but I have to

write

the music I have to write, and it doesn’t bother me. I don’t

think of it that way. It’s something you have to

do, and you do the best you can. I remember when I was getting my

bachelor’s degree from Manhattan, the

student orchestra had to play the graduating seniors’ pieces, or parts

thereof. We were only allowed ten minutes, and I had written a

twenty-five minute symphonic tone suite based on the poems of Warren

Ramon Jimenez. [Nicolas

Flagello was a composer and faculty member at Manhattan School of Music

from 1950-77.] Flagello just chopped off the last ten

minutes,

about four or five of the eleven pieces, and that’s where they started

and they played it to the end. I was in the girl’s room just

before the concert, and two of the violinists were in there fixing

their hair and I heard them say, “Oh, God! Why do we

have to play this stuff when we could be playing Brahms and

Beethoven?” I said, “Look, they were local boys somewhere,

sometime. Everybody has to start somewhere. You don’t

know. Of the seven people whose pieces you’re playing tonight,

one of them, maybe someday, will end up being a great composer.

How do you know they won’t?” Nobody thought particularly much of

Bach. His sons were more

famous than he was. He was just a respectable old gent turning

out a lot of music. I worried to Mr. Giannini one day about that

and he said, “If it was good enough for Bach to be conservative and old

fashioned, it’s good enough for us, Juli.” I had a teacher once

who

told me that if I didn’t write twelve-tone music I was not a musician,

not a composer. Tonal music was written out, and if I didn’t

write

twelve-tone music, all was lost. I said he had no right to

say that, that no one knew what was going to last in music or who was

going to last in music, and certainly using one tool only to write

music was a very cramping thing. I thought that then and still

think now.

BD: Who

decides what music will last

— is

it the public, the publishers, the group of

musicians that constitute the musical world?

JN: It may be

a little bit of everything. If

nothing gets published or played, how will anybody

know? I’m writing a symphony now. I don’t know whether I’ll

ever finish it, but I doubt if it will ever be played. So how do

you know? Publishing has something to do with it and performing

has

something to do with it. Now that we have radio and television,

that has something to do with it, and the people have something to do

with it. I’ve had experience with some of the dancers I’ve

taught at the New London Dance Festival some years ago, all modern

dancers — except

a very few who took a few ballet classes, and they were

very much against what I was doing for the first few weeks. But

they discerned and perceived what I was getting at, and

they came over. The school, Connecticut College, had a music

program every Wednesday night. Their own top advanced students

were playing, and I urged my

dancers — there were a whole lot of them; I taught three classes and

there were maybe nineteen or twenty in each class — to go any Wednesday

and hear this live music. My accompanist

and I used to go every Wednesday night to see if any of them did, and

gradually, as the seven or eight weeks went by, we found more and more

of them attending the

concerts. John and I used to hide because we didn’t want

them to see us. I remember hearing one girl as she came out of a

Mozart program say to another, “I thought when she was taking

that music apart that it was going to ruin it, but did you hear those

extensions? Weren’t they wonderful?” I said to John, “If we

didn’t do anything

else all summer but reach that one girl, we had achieved

something.” She was listening to music in a different way, and

that’s what I try to get the choreographers and dancers I teach to do

— to listen to it on that third

level, the musical level, and hear the

music that’s going on inside the music, the wonderful counterpoint and

all the evaded cadences and extensions, and to be

aware of the dynamics and what’s going on.

BD: How much

of this detail and how much of

this technical business should the actual public be aware of? The

performers, obviously, should be aware of much more...

JN: Yes, they

should. The

more a person is aware, the deeper will be his or her understanding,

enjoyment, and interest in the music. You can listen to

it in absolute ignorance, as my mother did, for example. She

refused to study music. She was very musical. She listened

to it and she loved a lot of it, but some of it was not for her.

For example, she would

tell me, “I don’t see how you can stand listening to Bach. There

are no melodies.” I tried to get her to study toward the end of

her

life, but I didn’t succeed, and then I just let it drop. But if

she had known something about the music and had been able to hear some

of those things I’ve been talking about, then I think she would have

enjoyed it more. Some of the music that she loved and

enjoyed, she loved and enjoyed in total ignorance of what was going on,

but something of it reached her. I think she would have loved and

enjoyed it even more had she known some of the things that the composer

was doing, but it’s not entirely necessary. It’s ridiculous to

think that everybody should

know everything about music in order to enjoy it. That’s

outlandish. But the more you know about it, the more

you do enjoy it.

BD: Is this,

perhaps, one of the things that

contributes to making a piece of music great

— that it has so many

things to learn and enjoy?

JN: Not

necessarily. One of the greatest

songs ever written is Im

Wundershoenen Monat Mai, [the

first song of Dichterliebe by

Schumann] which is

about four phrases long, and there isn’t a heck of a lot in it.

Simplicity — that’s one of the things I also teach and talk

about. Simplicity is a very, very wonderful thing, and some of

the

simplest music is among the greatest. I don’t think it’s

complexity. I just want people to know what is there, not just to

listen to the tune. That’s in my teaching choreographers and

dancers and dance teachers, because they don’t listen that way.

Of course, most

people who aren’t musicians hear very superficially, and I

think they’d enjoy it more if they knew more.

*

* *

* *

BD: Tell me

more about your special ideas of teaching.

JN: I only

teach choreographers

and dance teachers and dancers. I did teach composition when I

was at the Hathaway Brown School in Shaker Heights, but that was an

experimental course given to kids who knew nothing whatever about

music and had never even touched an instrument. They came up with

some fabulous things. One youngster wrote a perfectly beautiful

lullaby on the piano, and at spring festival we had professional

musicians play the things these kids wrote. Her mother

was dying of cancer and the family knew it, and the mother asked that

the berceuse be played at her funeral.

Another girl wrote a lovely Christmas carol. It was actually

lovely, and the whole chorus at the school played it. But what I

teach now is not music to musicians or composition to musicians, but

music to choreographers mostly, and that’s through the Carlisle

Project in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. It’s headed

by Barbara Weisberger, who founded and directed the Pennsylvania Ballet

Company for twenty years.

BD: So you’re

teaching them the understanding of the

music they use?

JN: Yes, yes,

and sometimes it’s the music they

choose. Sometimes it’s the music that I hand to them and they

have

to use it whether they like it or not. That’s very interesting,

and opens their eyes and ears. They discover that I’m trying to

open

doors and windows for them, and also widen their own musical

spectrum. Some of them, for example, still use Minkus and

Tchaikovsky, and some of them are

all for nothing but minimalist music or electronic music. Each

of these extremes has shut its ears, so to speak, to the

other. I try to put them all together in a bag and shake them

up. At the same time, I teach them what to listen

for, as Copland puts it, and how to hear it, and then how they can make

use of it choreographically.

BD: I assume

there’s no one answer to any one of

those questions.

JN: No,

indeed, there isn’t. There are many,

many answers, and that’s also what I try to show them. It’s not a

matter of ‘Mickey Mousing’

or ‘Scotch taping’, or

going up when the music

goes up and down when the music goes down. It’s knowing what’s

there, that you may use any aspect of what the composer has done if you

wish, that you may counter any one or more of those aspects, if you

wish, or you may ignore them altogether. But I don’t think you

can do, in choreography, any of those things with as much artistic

integrity and success if you don’t know what’s there to

be used or countered or ignored. When I say ignored, I mean using

the music as a

kind of scrim behind which to dance, or a backdrop before which to

dance, or simply a sound environment within which to dance.

BD: Do

you feel that the music you use for the dance can also stand on

its own without the additional movement of bodies on the stage?

JN: Of

course, it’s not my music they’re using.

BD: I mean

any music.

JN: Oh, yes.

Oh yes, of course! I love

poetry, so I’ve written a

great many poems as songs either for piano and voice or for chamber

instruments and voice, or now this choral symphony or choral

music. I have always had the feeling when I’m studying a poem

that what I’m doing is trying to pay a tribute to the poem,

to give it another dimension, and it’s because I think the poem is so

wonderful. Perhaps that’s egotistic, but I

feel as if I’m paying homage to the poem, and I do the best I can to

express what the poet has expressed in my medium as best I can, and

that’s what I want them to do as they honor the music with the

dance. They don’t just use it as a crutch or something to count

to. It’s an equal partner; it’s another leg. It’s not just

something that has a beat that they like or a tune that they like, and

somebody would look nice in mauve dancing to it, or it

would fit a story that they like. They should treat the music

with great respect.

JN: Oh, yes.

Oh yes, of course! I love

poetry, so I’ve written a

great many poems as songs either for piano and voice or for chamber

instruments and voice, or now this choral symphony or choral

music. I have always had the feeling when I’m studying a poem

that what I’m doing is trying to pay a tribute to the poem,

to give it another dimension, and it’s because I think the poem is so

wonderful. Perhaps that’s egotistic, but I

feel as if I’m paying homage to the poem, and I do the best I can to

express what the poet has expressed in my medium as best I can, and

that’s what I want them to do as they honor the music with the

dance. They don’t just use it as a crutch or something to count

to. It’s an equal partner; it’s another leg. It’s not just

something that has a beat that they like or a tune that they like, and

somebody would look nice in mauve dancing to it, or it

would fit a story that they like. They should treat the music

with great respect.

BD: Does it

then become visual poetry?

JN: Oh, I

don’t think so. There’s always this

never-ending argument about the dancer is the dance, or

shouldn’t the dance all be done without music and stand on its own, and

so forth. I have lots of

reasons why choreographers use music, why dancers use music. One

day as I was leaving to go teach I asked my husband, “What’s another

reason that people use music for dance?” and he

said, “The box office would drop off if they didn’t.” [Both

laugh] There are lots of very good reasons for using

music, but I don’t like to think of them as using music. I like

to think of them as marrying their art to the art of music. One

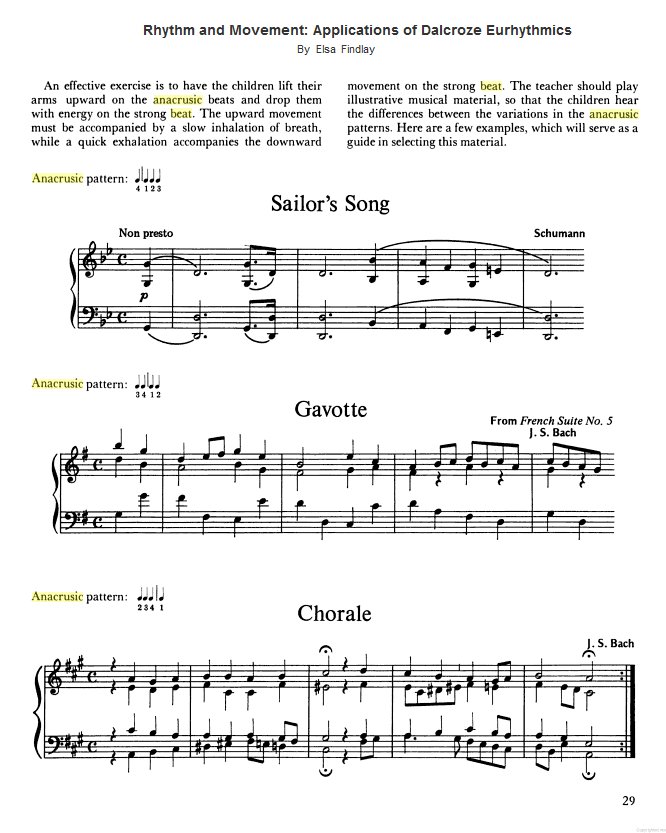

of the things that I’ve been trying to do for twenty-six years is

to get musicians to understand dancers, and dancers and choreographers

to understand

musicians. A lot of musicians, at least in my

experience, tend to look down at dancers, because dancers don’t count

the way musicians count. They don’t at all, and they

shouldn’t. They needn’t. Their counting is different and it

must be different, and it’s perfectly all right that they differ.

But the thing that I want them to do is understand how the musicians

count so they can meet the musicians on their own ground. They

need to explain to the musicians, “I understand that this is an

anacrusic beat, and you’re going to count it as 3-4-1, but I am going

to

count it as 1-2-3, and this is my reason.” They have a perfectly

good reason for it, and I try to get this gap between musicians

and dancers closed as best I can.

BD: Are you

succeeding?

JN: Oh,

heavens! I’m only one person in a great

big bucket! [Laughs] I don’t

deal with the musicians, I’m dealing with the choreographers, so I have

to work it from one side only. If I could get a bunch

of musicians together and show them what dancers mean by their count,

that would be fine, but I’m only one person, and I have a lot of other

things to do, and it’s the dancers I’m involved with. So I try to

get them to understand musical counts so that they can at least show

the musicians they work with that they do. Then they can also

make a case for their own way of counting. They do have a

legitimate way of counting and it’s very strange, but it’s perfectly

effective and usable. It’s

just I’d like them to understand musicians’ counts, and if I

could get a whole bunch of musicians together, I’d like them to

understand dancers’ counts, too. If I ever get finished with the

book that I’m

supposed to be trying to write, then maybe some musicians would

understand, because I have some marvelous pages of music on which

dancers have scrawled their count in inch-high pencil marks, and it’s

fascinating to see what they’ve done.

BD: So it’s

to take the scores that the

musicians know, and then see how the dancers view them.

JN:

Yes. For example, if you

take something that’s very straightforward, four bars, eight bars, and

it’s all in 4/4, 2/4, that’s just fine. But when you get

something like Copland’s Piano Sonata,

the second movement changes

meter darned near every measure and goes all over the place.

There’s no way in heaven that a choreographer can teach his dancers

that count. The dancers are up there on the stage and they

don’t have anything to look at. They don’t have any map, and

there’s no

way the piece can be counted in a straightforward enough way so that

they

can use the counts that Copland has put there, the beats, the

meters. They have to find their own way. I had one young

man

last summer who was absolutely marvelous! He

found a way to count that with dancers’ count so that his dancers

understood completely what was going on in the music. They

couldn’t

under any circumstances have understood it if he had tried to count

them as a musician would. He scrawled all over the page these

immense,

“A one-y and a two-y and a three, four, five and a one-y and a two-y

and a three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, and a

one-two-three.” It was fantastic! His dancers

understood immediately and they heard it in the music. What

he was doing was listening to the motivic elements that Copland was

using, and he was getting the kids to listen and hear the development

of those motivic elements.

BD: Is there

any reason, then, to transfer this dance

counting back to the musician to understand the music better?

JN: Copland

probably understood his music well

enough. I don’t think a musician could use a

dancer’s counts, no, if that’s what you mean, but if they could be

brought to understand if

they could have seen and heard what I saw and heard last summer with

Chris Fleming, who’s now in Bogota, Columbia, as director

of some ballet company there. They would then understand very

clearly, I think because it only takes one really good example, and he

certainly gave me one.

*

* *

* *

BD: Tell me

about the particular joys and sorrows of

writing for the human voice.

To read my Interview with Phyllis Curtin, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, click HERE.

|

JN: One of

the sorrows in the

beginning is that I always wrote everything down where I could sing it,

and since I sang with the tenors and basses in the high school glee

club, I always put it too low for women and too high for men. So

the first songs that I wrote — and there must be

a hundred of them — a

lot of them would have to be transposed to get anybody, male or female

human, to sing them. But it’s always a joy to write for the human

voice, and it depends

on who sings it and how well they sing it, where the joy lies in

hearing it. It’s always wonderful to hear your music, but I agree

with something Mr. Giannini said many years ago when we all trooped to

Carnegie Hall to hear a first performance of one of his

symphonies. We rushed down from the balcony afterwards and met

him coming up the aisle to tell him how wonderful it was. He was

beet red and he said, “Whenever I hear my music, half of me

wants to sit there and listen, and think ‘Gosh, I wrote that,’ and the

other half of me wants to be up on the stage beating the musicians into

doing what I want, and the other half, the third half, wants to be a

thousand miles away.” And that’s how you feel if it isn’t done

really well. But I am grateful when it’s done at all because I’m

not an operator

and I don’t get a lot of it performed. But when I hear it, I’m

extremely happy to hear it, and I don’t really mind if they blow it

a bit here and there, except on the two records

that I never tell anybody about.

BD: May I ask

briefly about those so I will know why you dismiss them?

JN: I’m not

happy with them. Mr.

[Arthur] Loesser was marvelous to me, and at the rehearsal he not only

played

them beautifully, but he showed me where I’d written something

wrong. He said, “You don’t mean this?” and he played it the

way it was notated. Then he said, “You mean this, don’t

you?” and played it slightly differently, and I said, “Oh, yes.”

So he said, “Then this

is how you should notate it.” So I learned, and I learn every

time, and that’s without fail. I’ve learned every time anybody’s

played my music how I could notate it better, what’s wrong with the

notation, and what would make it easier for the performer.

Anyway, he played them beautifully, and then the day that they were

recorded by that company, he performed

other music on the record, and he promised

us he wouldn’t teach. But he taught all day long. The other

two

composers, whose music he played, were there in the recording studio,

working with him, and I had to be in Jersey. My mother had fallen

and broken her hip.

BD: Who were

the other two composers?

JN: Marcel

Dick and Jane Corner Young. They

were there, and he played their music over and over

again. He was very tired, and he only went through mine

once.

He apologized later, and said he wanted to do

them again because he did them very badly. He said that

himself, and he wanted to record them again, but the Cleveland

Composer’s Guild could not afford to do another recording of

them. So I don’t ever tell anybody about that disc. On the

other one they

only did four of the six pieces, which was uncomfortable anyway.

I would

have loved very much to have all six of the whole cycle done. The

tenor soloist was a shade flat, and then a perfectly dreadful thing

happened at the end. The sound was all right. It was dry

and clear and good, and the chorus was not bad, but this chap, who

had promised not to do it, put this echo chamber sound on it and ruined

it. It’s dreadful! I played it once many,

many years ago and I’ve never played it since. I can’t stand

to!

BD: Now you

have this new recording out, and I

assume you’re pleased with it?

JN: Yes, I

am. It could be better,

but it’s the best I’ve had, and I’m pleased with it.

BD: Have you

basically been pleased with

the other performances you’ve had of you works?

JN: In some

sense, yes. Sometimes

they’ve been done with real TLC and I have been happy with them, but

none of them has been perfect. I don’t suppose anyone has a

perfect performance, but none of them has been. Even when there’s

been a pretty good performance, I’ve never had a

really good taping. Something always seems to

be slightly amiss, but I think that’s probably generally true of

everyone, unless he or she has reached a place where truly professional

performances with truly professional recordings are done. I’m

always happy to hear it, but I would like it to be even

better, and more of it, but that’s human.

BD: I want to

ask you a question that

you may not be able to answer. Is it harder being a woman

composer than being

a man composer?

JN: [Laughs]

It is impossible to say. It’s

probably a lot easier now for women, and growing easier all the time

partly because of people like you and things like the American Women

Composers. Many more women seem to be writing music, or at least

having a chance. Maybe lots of women wrote it in earlier times

and never

had a chance for anyone to know it. That’s quite possible, but

probably more women are writing now and

more women are being recognized as composers and having their works

performed and published and recorded. There’s a recording company

that records a lot of women’s music. I’ve

forgotten the name of it at the moment, but I met the woman who

started it at one of the conferences of American Women Composers.

JN: [Laughs]

It is impossible to say. It’s

probably a lot easier now for women, and growing easier all the time

partly because of people like you and things like the American Women

Composers. Many more women seem to be writing music, or at least

having a chance. Maybe lots of women wrote it in earlier times

and never

had a chance for anyone to know it. That’s quite possible, but

probably more women are writing now and

more women are being recognized as composers and having their works

performed and published and recorded. There’s a recording company

that records a lot of women’s music. I’ve

forgotten the name of it at the moment, but I met the woman who

started it at one of the conferences of American Women Composers.

BD: That

sounds like it would be Leonarda.

JN: Yes, just

as the Alice

James Books in Cambridge publishes mostly women’s poetry. Things

are looking up for women in the arts and in composition

especially. In any event, I don’t know what it’s

like to be a man composer. [Both laugh]

BD: Of

course! Perhaps an easier question would be is there a noticeable

difference between music

that has been written by a woman and music that has been written by a

man?

JN: Not to

me. There was a panel

about that at an American Women Composers conference at Boston

University a couple of years ago when I had a couple of my choral

pieces sung. It was a three or four-day conference, and there was

a panel “Is there a difference, and can you tell the difference?”

and nobody could make up anybody’s mind on that. Some people

thought there might be a difference, and some thought there might not

be a difference, and some didn’t know whether they could tell and

didn’t know that it made any difference. I don’t know that I

could tell. If some of my music was played and you

didn’t know I’d written it — especially,

perhaps, some of the symphonies

that I’m working on — I don’t think you could

tell what gender had

written it. I really don’t.

BD: Do you

want to be known as a woman composer

or simply composer?

JN: A

composer. It’s just like asking if you want to be called a

poetess or a poet? I would rather be a poet, and not a woman

poet. The only time that that feminine ending seems to be

acceptable to me is ‘actress’.

Katherine Hepburn or Maude

Adams are great actresses, and so-and-so is a great actor. There

I seem to accept — and most people seem to accept

— the separation of the

sexes, but not in anything else.

BD: There’s

no such word

as composer-ess, which I suppose is very good. [Both laugh]

JN: Yes, it

is. It’s very good. I think

probably the use of ‘woman composer’

is partly because they are just

beginning to flourish. I hope it dies out in the end, and that Ruth

Lomon is just a composer, or Emma Lou Diemer is just a composer, or

whoever it is they’re talking

about is just a composer and not a ‘woman composer’.

That’s what I would hope.

BD: I put the

same question when I interview black

composers, and most of them say they want to be just simply composers.

JN:

Yes. I understand why those terms have

developed in the period through which we’ve just been living

— the ‘black’

and the ‘woman’ — because

these groups are just really beginning to

surface. The way to get around that when you’re talking about the

composer is that you use

the words ‘she’ and ‘her’,

and then they know. But you won’t have

labeled the person as a ‘woman composer’

or a ‘black composer’.

I don’t know how you can get around it with

a black person except by putting a picture out that shows, and

even then you can’t always tell.

BD: A couple

of times

I’ve been surprised one way or the other.

JN: Yes, so

have I with choreographers.

*

* *

* *

BD: I assume

that you are pleased with all the

strides that music has been making in the last many years?

JN: Oh yes,

indeed I am. With all

the experimenting and all the whatever’s going on, and the more that

it’s played and the more that it’s listened to and the more that it’s

published and the more that it’s recorded, the better I like it.

[Laughs]

BD: Is there

ever a time when we get too many

composers writing, or too many recordings being made?

JN: I don’t

know. It would be the sort

of thing that Giannini meant when he said that the vast majority of

things that will last will last, and the rest will be lost in the dust

heap. Of course you can always say that there are the wonderful

ones that aren’t discovered. Bach wouldn’t have been

discovered if Mendelssohn hadn’t done it.

BD: Are we

throwing a joker into this

now with the business of recordings where nothing is

actually lost? We no longer have to take a piece of music off the

shelf and perform it. You can put a platter onto a disc machine

and hear the music even if you’re not a particularly good

performer.

JN: Yes you

can, and that’s a wonderful

thing. I have all my stereo equipment and listen to

great music, and I think that’s wonderful. People who didn’t have

that in other centuries lost a lot. They had to go to live

performances, and very often couldn’t. But to be at a live

performance is a very special thing.

BD: That is

still the best!

JN: Still the

best, yes, although I wouldn’t give up

my records and tapes and everything else that I have because I

live in the Boonies and it’s very hard to get even into Worcester in

the winter. So I forego a lot of live performances for that

reason, and because of the weather and the ice and so on, but I have

the music at home and I don’t think

there can be too much of it. Why would there be too much of

it? How

could there be too much of it?

BD: Well, at what

point does the avalanche of

material just become too much for people to explore in a lifetime?

BD: Well, at what

point does the avalanche of

material just become too much for people to explore in a lifetime?

JN: Well, you

could say that of the whole world. I can’t explore it all.

I have to explore very little of the world,

but I’ve explored what I could, and surely I will have

missed out on some marvelous music that I’ve never heard of, but I

can’t help that. I’ll explore what I can, and the fact that

there’s a whole lot out there that I’ll probably never hear doesn’t

mean it shouldn’t be out there for somebody else to hear. I’m

limited in what I can buy, where I can go, what I can get to hear, but

that doesn’t mean that a whole lot of other stuff shouldn’t be out

there that somebody else can buy or get to hear. It’s like saying

can there be too much poetry. There’s going

to be good, bad and indifferent poetry. There’s going to be great

and

excellent and good poetry. There’s a poem by Robert Frost, called

A

Minor Bird, and why should his

song be less important than, for example — and here I’m leaping

around a bit — Borodin? If he had written

nothing

but that string quartet which has the great nocturne in it with the

marvelous canon, I would consider him a great composer.

[Laughs] I

would consider Schumann a great composer if I’d never heard anything

but Im Wundershoenen Monat Mai.

You can have one gem and be great. You do not have to write an

enormous

body.

Many did, and praise be. Thank the Lord!

BD: Is Juli

Nunlist a great composer?

JN: Oh, I

don’t think so. I would never

presume to say that. I would like to be a good composer, and I

think some of my things are very good. If I can finish my

symphony

and the French songs I spoke of, I would die happy... although I have

the feeling they’ll never be

played. I can envision my wonderful, lovely daughter-in-law,

twenty

or thirty years from now, finding the manuscript on a shelf and saying

to her husband, “Oh, Mark, we need this space. What’ll I do with

this?” and they’ll both say, “Heave it out!” It’s biodegradable,

anyway.

BD: Oh,

no! I would hate to think that all of

your labor on the symphony would be lost.

JN: Well, I

would hate to think so, too, and I’m

going to endeavor that it not be. I have gotten some very good

advice. There was a very interesting lecture at that conference

on Ruth Crawford Seeger. It appeared that she had been granted a

Guggenheim Foundation fellowship for $5000 to complete a

symphony, and she had never completed it. I went up to a

woman afterward who had been part of the

panel and I said, “Do you think it’s possible that at the time she was

granted this $5000 that she did not finish her symphony

because she thought, believed, or knew that it would never be

performed?” and the woman agreed. She said it’s quite possible

that’s why she never finished

it, because in her day to play a woman’s symphony would have been just

extraordinary. I told her that the reason I was asking was

that I was working on a choral symphony, and she immediately

said, “When it was finished, do not show it to

an orchestral

conductor. Show it to a choral conductor. He will want his

chorus to sing it, and he’ll

badger some orchestral conductor into performing it so his

chorus can sing it.”

BD: We have a

couple of fine ones in this area,

of course — Margaret Hillis and

also Thomas Peck

JN: Yes, I’m

familiar with

both of them. Of course I have to finish the thing

first. It’s about three-fifths done.

BD: What

advice do you have for the young composers

coming along?

JN: Work hard

and write a hell of a lot. I

don’t suppose you can put that on the air... [I reassured her that her word was not

something I would need to edit out.] Keep working and

working and

working. When I was in school, I was old enough to be

the mother of all the six others in my class, and I went along busily,

working at everything everybody gave us to do. We had five

composition courses. Giannini taught harmony and counterpoint,

and Flagello taught orchestration, and Ulehla taught ear training

and form and analysis. We met once a week

and had homework for each of those subjects each week. At the

same time, for each of the three teachers we were writing a

composition, and it wasn’t the same. You couldn’t write a sonata

and have one movement for Flagello, one movement for Giannini and one

for Ulehla. You had to write your string quartet for Giannini,

and your piano pieces for Ulehla, and your opera

scene for Flagello. So we were just drowned in things to

do, but it was wonderful because you were never blocked. There

was so

much to do that when you got stuck you could just turn to another piece

or another bit of homework and do that. I remember I worked

and worked and worked and worked, and I had a

marvelous time! I always did my

homework, always, always, always for all of them. One time toward

the end of my first year, something happened in my life, I’ve forgotten

what, and I

couldn’t do Mr. Giannini’s work for that week. I went into school

feeling perfectly dreadful. I had a migraine headache and it

must have shown. I was almost ill in his classroom, and before he

knew me very well he said, “Miss Nunlist, what is the

trouble?” He took me over to a little room that had a daybed, and

he put me down, got me some water and an aspirin and asked, “What

is the matter?” I said, “Mr. Giannini, I couldn’t do

your work,” and he just shrieked! He hooted with laughter and he

said, “Haven’t you noticed how all the rest of them have been

saying, ‘This isn’t your week, Mr. Giannini,’ or ‘This isn’t your

week, Miss Ulehla’?” They hadn’t done the work week after week,

but I

always had. I wrote all the time, and that’s my advice

to anyone who wants to write — just do it all

the time.

BD: Do you

take your own advice to this day?

JN: As much

as I possibly can, yes.

*

* *

* *

BD: I want to

be sure and ask you

about your opera.

JN:

[Laughs] Oh, my opera. That was

funny. That was a Flagello assignment for a five-minute opera

scene, and everybody else did exactly that — a

five-minute opera

scene — but I didn’t. I wrote a

fifty-minute one-act opera based

on Chaucer’s The Pardner’s Tale.

It didn’t occur to me to stop

once I got started. I just finished the whole thing, and

Flagello liked it and the class liked it. One of the young

men who was very gifted said, “You’ve written a

real American folk opera.” But the funny thing is I was in a

music school where there were hoards and hoards of girls studying

voice, and my opera is for six men. The only possibility for a

woman-part would be

for the young lad who is the tavern boy, the servant in the tavern, who

could be an alto who looked boyish. It’s ridiculous to write an

opera for all men, but I did.

BD: Has it

been performed?

JN: No, it

never has.

BD; Do you

want it to be performed?

JN: Oh, I’d

love to have it be performed. At

the moment it’s only in a piano edition; it has only a

piano accompaniment. I’ve never scored it. For years I’ve

said that someday I’ll score it for chamber orchestra, and then

maybe some college would do it, but I’ve never done it. I’ve just

been busy doing other things.

BD: When you

get finished with the symphony, maybe

that’s your next project.

JN: Well,

that might be so. I also have started

a suite for a youth string group, and I would like to

finish that. I’ve also got another project that I’d love to

do, and that’s a choral piece with a whole bunch of little prayers and

curses. I would like to do that.

BD: Would you

ever orchestrate some of these songs

that are on the record? That was one of the first things I

noticed when listening to them — that

they would sound wonderful as orchestral songs.

JN: Oh, I’d

love to do that. One of my most favorite compositions in all the

world

is The Songs of the Wayfarer

of Mahler, and they are orchestrated.

BD: Would you

be adverse to someone else

orchestrating your work?

JN: Well,

yes, unless I knew that person.

BD: Either

now or, perhaps, in twenty-five years?

JN: In

twenty-five years probably anybody

could because I won’t be here. But, for example, if Ronald Perera

wanted

to do it, sure. I’d let him in a minute. He’s a wonderful

composer and teacher and human

being, and has been great to me. He’s the person I go to.

He’s a sort of mentor, and I bring him my music and we discuss it, and

he shows me how to enrich my orchestration and things like that.

If somebody like that would do it, it would be

marvelous. But he’s busy teaching and composing at Smith College

at

Northampton.

BD: I

appreciate your spending the

time with me this afternoon. This has been just a wonderful

conversation. I have learned a lot, and I’ve become very much

inspired by what you’ve had to say.

JN: Well,

thank you very, very much. It’s been

a great pleasure to me, too.

|

This CD (released in 1998)

contains the 12 Bagatelles for Solo

Flute by Nunlist.

To read my Interview with John Cage, click HERE.

To read my Interview with Vivian Fine, click HERE.

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on

August 28, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1997.

This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this

website

at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been

transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award

- winning

broadcaster

Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975

until

its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His

interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since

1980,

and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well

as

on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website

for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of

other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also

like

to call your attention to the photos and information about his

grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a

century ago. You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

JN: Of course, in

the beginning they were quite

simple, although my husband’s step-mother was a musician. She was

a graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory,

and she heard me doodling at a little contrapuntal piece one day in

their home. She asked what it was and I told her it was a piece

that I wrote, and she said, “You really

should study music.” This was before I was even married. I

wrote songs in German and English, not in French

until later, but I wouldn’t change some of them now. Some

of them I would, of course, but for what they were I was pleased.

They were

those of a one-handed pianist, in a way, because I wasn’t a very good

pianist, and the right hand did a lot more than the left hand. I

had to learn a lot about that when I

started studying music. When I started studying

the piano seriously, which was about a year and a half before I went to

Manhattan School, David Jatovsky was my piano teacher. He was a

great musician and a great teacher, and I learned an immense amount

from him. Knowing that I mainly wanted

to compose, he taught me not only how a piano should be

played and how it should sound, but that it was in itself an

orchestra. That is, it had all the range of the orchestral

instruments. I was shown how to use that because I always

composed at the piano, and he showed me how to use it not as a pianist,

but as a person thinking in terms of chamber music, orchestration and

things like that, and I’m very grateful to him for that.

JN: Of course, in

the beginning they were quite

simple, although my husband’s step-mother was a musician. She was

a graduate of the San Francisco Conservatory,

and she heard me doodling at a little contrapuntal piece one day in

their home. She asked what it was and I told her it was a piece

that I wrote, and she said, “You really

should study music.” This was before I was even married. I

wrote songs in German and English, not in French

until later, but I wouldn’t change some of them now. Some

of them I would, of course, but for what they were I was pleased.

They were

those of a one-handed pianist, in a way, because I wasn’t a very good

pianist, and the right hand did a lot more than the left hand. I

had to learn a lot about that when I

started studying music. When I started studying

the piano seriously, which was about a year and a half before I went to

Manhattan School, David Jatovsky was my piano teacher. He was a

great musician and a great teacher, and I learned an immense amount

from him. Knowing that I mainly wanted

to compose, he taught me not only how a piano should be

played and how it should sound, but that it was in itself an

orchestra. That is, it had all the range of the orchestral

instruments. I was shown how to use that because I always

composed at the piano, and he showed me how to use it not as a pianist,

but as a person thinking in terms of chamber music, orchestration and

things like that, and I’m very grateful to him for that. JN: Oh yes, I think

so. Maybe it’s a

gray area. I have Aaron

Copland’s book, What to Listen for

in Music. I use that in teaching, and it’s the history of

levels of musical consciousness. First, the sensuous one where I

tell my

students, “You all do your homework or other chores to music you

like. It’s entertaining and you love it, but you don’t even hear

it. You’re doing your homework, but you’re in this bath of

sound, and then suddenly you hear a piece that you love.

It’s your favorite, and you drop your homework and you listen.

You’re entertained. Then when that piece stops and the rest

goes on, you go back to your homework.” The second level, as he

says, is the level where you see the

children playing, or the rainy day, or the funeral procession.

I’ve forgotten what he terms it, but then the last

level is the musical level, and that’s the level where you move into

art. Everyone can be entertained at some time by listening to a

piece he loves, but it’s not the same thing as deliberately composing

it or listening to a Mozart symphony. I’m not sure that there’s

a line I can draw. I am, if you wish to use the word, entertained

when I listen to great music. I don’t know whether it’s the use

of the word that troubles me or not. I am moved and uplifted, and

if you wish, entertained. I have a youngster now

who wants to “learn to play the piano.” I’m not a piano

teacher. She works for me a little and she wants me to show her

how to play the piano. She starts out with the theme song of The Pink Panther because her father

likes it. She brings me that music, which she has

borrowed from a girlfriend, and I say, “Fine, we will

start, and you will learn how to play the theme song to The Pink

Panther.” Through music that is entertaining to her I hope

to draw her into music

that will mean more to her. One of the reasons I stopped taking

lessons myself when I was seven or eight was that I was studying the

recital pieces which were The March

of the Dwarfs and The

Norwegian Dance by Grieg. They were very difficult pieces

for a

seven year old, and I don’t know how I played them. They must

have sounded terrible! But the reason I stopped wasn’t only the

recital; it was because I was in love with Vagabond King,

which was just new when I was seven, and I wanted to learn to play some

of the music

from it. But my teacher wouldn’t hear of it. She was so

rigid! She said, “I won’t help you with any of that,” and I

said, “Then I won’t work with you on any of the

others.” I think she made a mistake, but I’m not sorry she

made it, because I think she was a very bad piano teacher! [Both

laugh] But I don’t think it’s a good idea to look down

on something that is entertaining. I was in an Operetta Club in

Montclair when I was in high school, and we did all the D’Oyly Carte

operettas

and we did Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml and you name it. I

was happy as a clam and I loved doing it, and it brought me a

lot closer to music.

JN: Oh yes, I think

so. Maybe it’s a

gray area. I have Aaron

Copland’s book, What to Listen for

in Music. I use that in teaching, and it’s the history of

levels of musical consciousness. First, the sensuous one where I

tell my

students, “You all do your homework or other chores to music you

like. It’s entertaining and you love it, but you don’t even hear

it. You’re doing your homework, but you’re in this bath of

sound, and then suddenly you hear a piece that you love.

It’s your favorite, and you drop your homework and you listen.

You’re entertained. Then when that piece stops and the rest

goes on, you go back to your homework.” The second level, as he

says, is the level where you see the

children playing, or the rainy day, or the funeral procession.

I’ve forgotten what he terms it, but then the last

level is the musical level, and that’s the level where you move into

art. Everyone can be entertained at some time by listening to a

piece he loves, but it’s not the same thing as deliberately composing

it or listening to a Mozart symphony. I’m not sure that there’s

a line I can draw. I am, if you wish to use the word, entertained

when I listen to great music. I don’t know whether it’s the use

of the word that troubles me or not. I am moved and uplifted, and

if you wish, entertained. I have a youngster now

who wants to “learn to play the piano.” I’m not a piano

teacher. She works for me a little and she wants me to show her

how to play the piano. She starts out with the theme song of The Pink Panther because her father

likes it. She brings me that music, which she has

borrowed from a girlfriend, and I say, “Fine, we will

start, and you will learn how to play the theme song to The Pink

Panther.” Through music that is entertaining to her I hope

to draw her into music

that will mean more to her. One of the reasons I stopped taking

lessons myself when I was seven or eight was that I was studying the

recital pieces which were The March

of the Dwarfs and The

Norwegian Dance by Grieg. They were very difficult pieces

for a

seven year old, and I don’t know how I played them. They must

have sounded terrible! But the reason I stopped wasn’t only the

recital; it was because I was in love with Vagabond King,

which was just new when I was seven, and I wanted to learn to play some

of the music

from it. But my teacher wouldn’t hear of it. She was so

rigid! She said, “I won’t help you with any of that,” and I

said, “Then I won’t work with you on any of the

others.” I think she made a mistake, but I’m not sorry she

made it, because I think she was a very bad piano teacher! [Both

laugh] But I don’t think it’s a good idea to look down

on something that is entertaining. I was in an Operetta Club in

Montclair when I was in high school, and we did all the D’Oyly Carte

operettas

and we did Victor Herbert and Rudolph Friml and you name it. I

was happy as a clam and I loved doing it, and it brought me a

lot closer to music. JN: Oh, yes.

Oh yes, of course! I love

poetry, so I’ve written a

great many poems as songs either for piano and voice or for chamber

instruments and voice, or now this choral symphony or choral

music. I have always had the feeling when I’m studying a poem

that what I’m doing is trying to pay a tribute to the poem,

to give it another dimension, and it’s because I think the poem is so

wonderful. Perhaps that’s egotistic, but I

feel as if I’m paying homage to the poem, and I do the best I can to

express what the poet has expressed in my medium as best I can, and

that’s what I want them to do as they honor the music with the

dance. They don’t just use it as a crutch or something to count

to. It’s an equal partner; it’s another leg. It’s not just

something that has a beat that they like or a tune that they like, and

somebody would look nice in mauve dancing to it, or it

would fit a story that they like. They should treat the music

with great respect.

JN: Oh, yes.

Oh yes, of course! I love

poetry, so I’ve written a

great many poems as songs either for piano and voice or for chamber

instruments and voice, or now this choral symphony or choral

music. I have always had the feeling when I’m studying a poem

that what I’m doing is trying to pay a tribute to the poem,

to give it another dimension, and it’s because I think the poem is so

wonderful. Perhaps that’s egotistic, but I

feel as if I’m paying homage to the poem, and I do the best I can to

express what the poet has expressed in my medium as best I can, and

that’s what I want them to do as they honor the music with the

dance. They don’t just use it as a crutch or something to count

to. It’s an equal partner; it’s another leg. It’s not just

something that has a beat that they like or a tune that they like, and

somebody would look nice in mauve dancing to it, or it

would fit a story that they like. They should treat the music

with great respect. JN: [Laughs]

It is impossible to say. It’s

probably a lot easier now for women, and growing easier all the time

partly because of people like you and things like the American Women

Composers. Many more women seem to be writing music, or at least

having a chance. Maybe lots of women wrote it in earlier times

and never

had a chance for anyone to know it. That’s quite possible, but

probably more women are writing now and

more women are being recognized as composers and having their works

performed and published and recorded. There’s a recording company

that records a lot of women’s music. I’ve

forgotten the name of it at the moment, but I met the woman who

started it at one of the conferences of American Women Composers.

JN: [Laughs]

It is impossible to say. It’s

probably a lot easier now for women, and growing easier all the time

partly because of people like you and things like the American Women

Composers. Many more women seem to be writing music, or at least

having a chance. Maybe lots of women wrote it in earlier times

and never

had a chance for anyone to know it. That’s quite possible, but

probably more women are writing now and

more women are being recognized as composers and having their works

performed and published and recorded. There’s a recording company

that records a lot of women’s music. I’ve

forgotten the name of it at the moment, but I met the woman who

started it at one of the conferences of American Women Composers. BD: Well, at what

point does the avalanche of

material just become too much for people to explore in a lifetime?

BD: Well, at what

point does the avalanche of

material just become too much for people to explore in a lifetime?