|

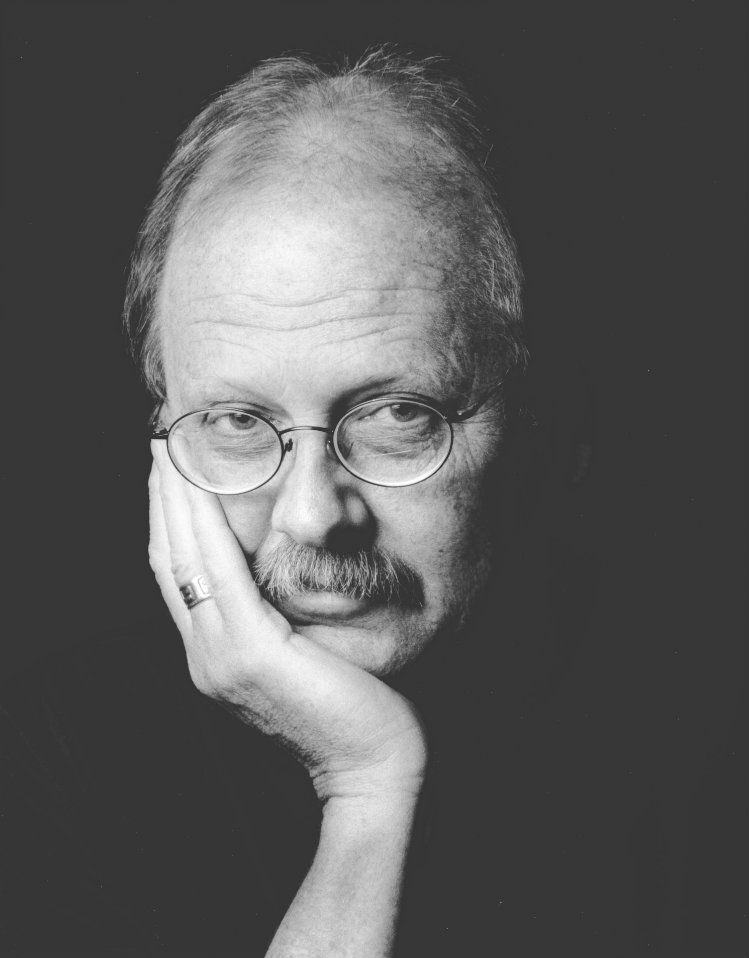

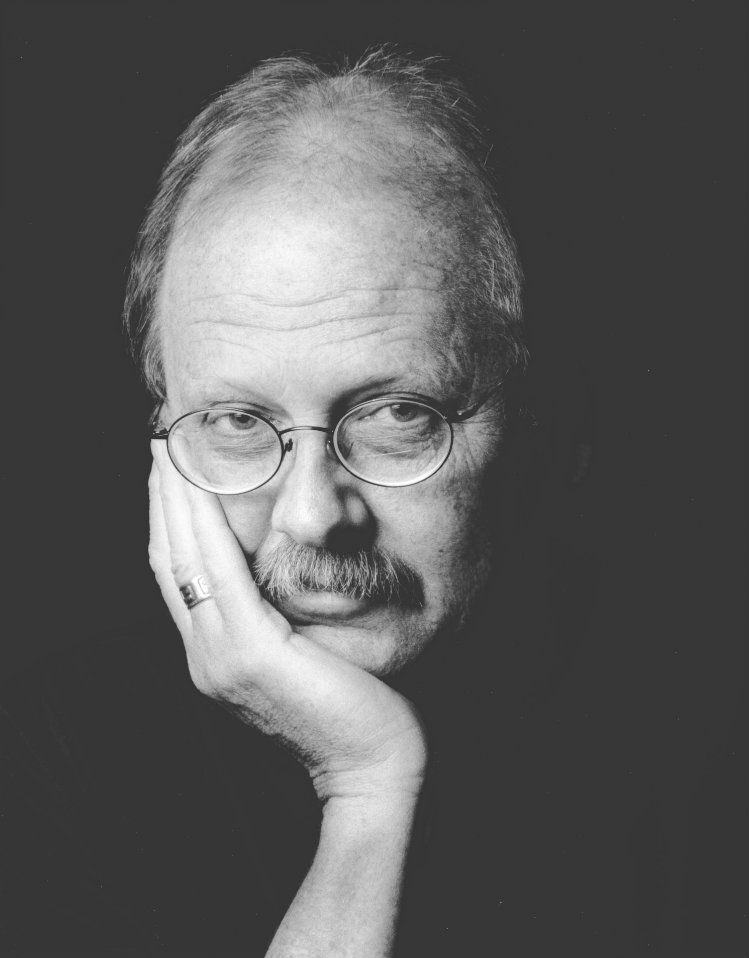

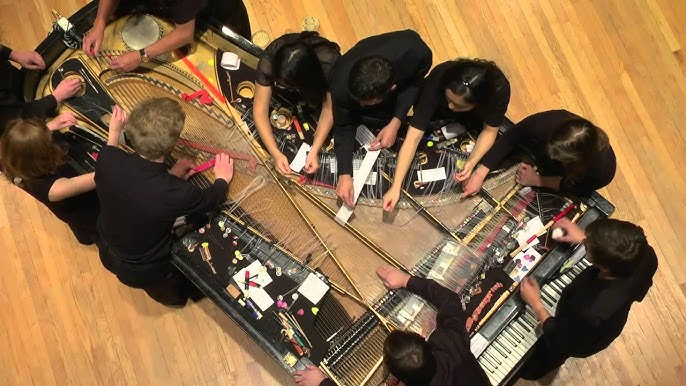

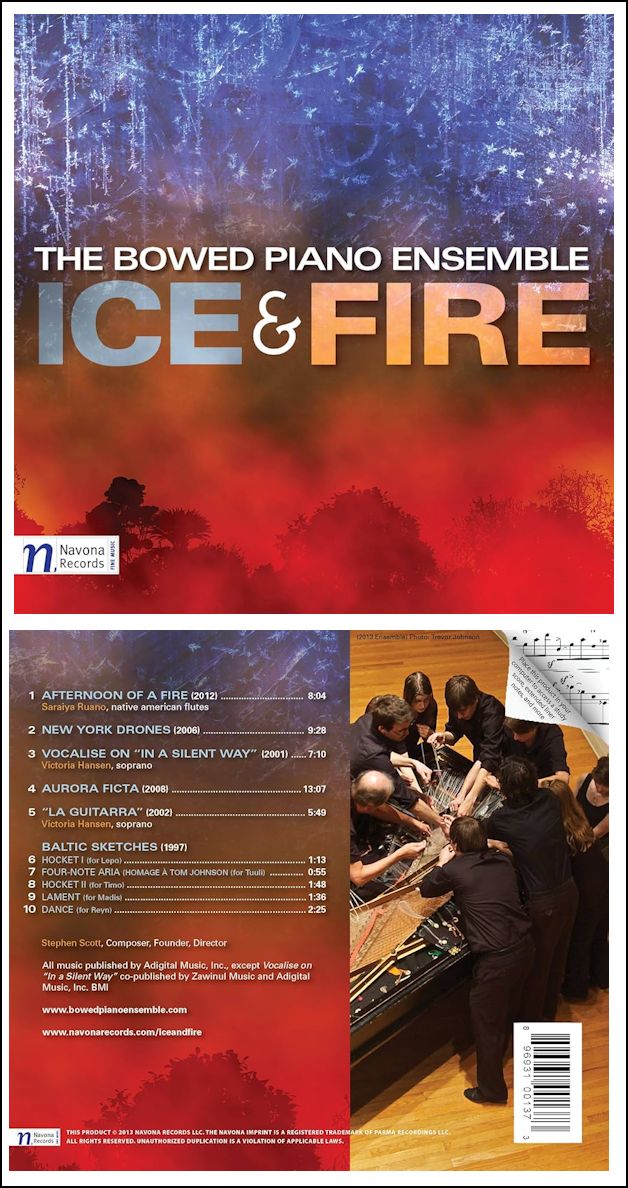

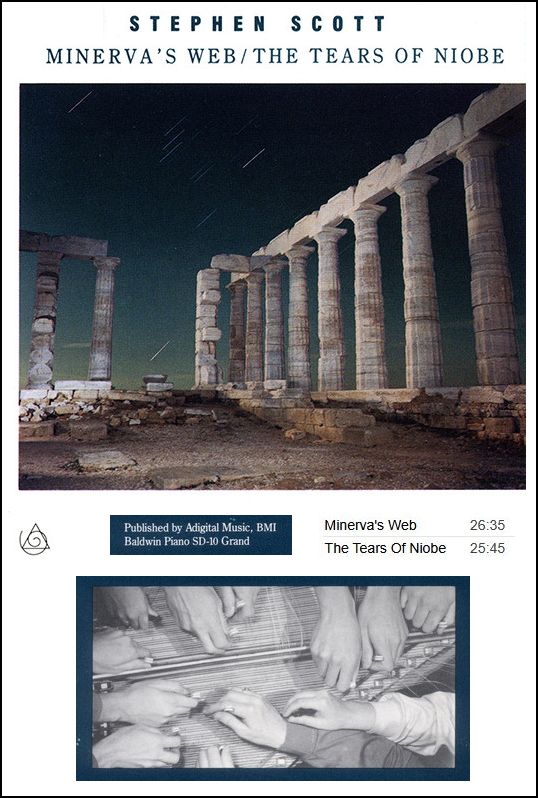

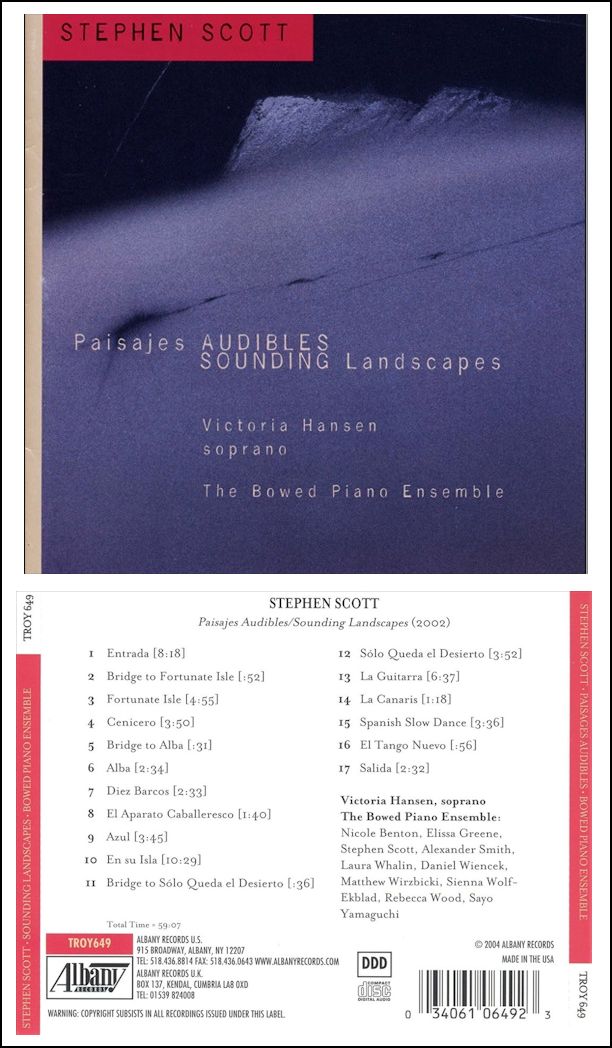

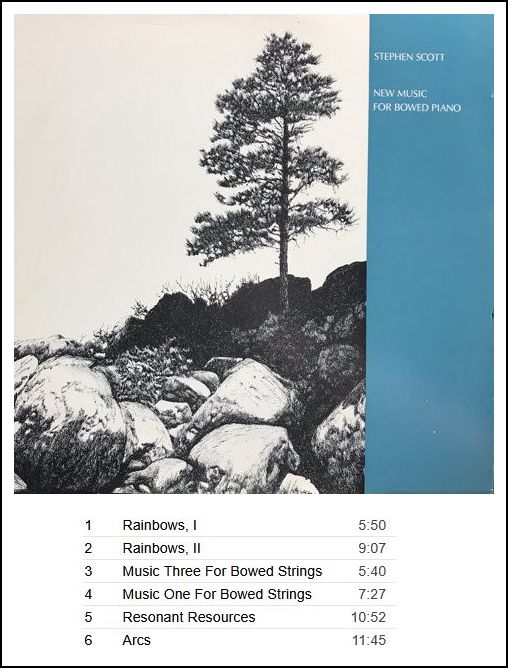

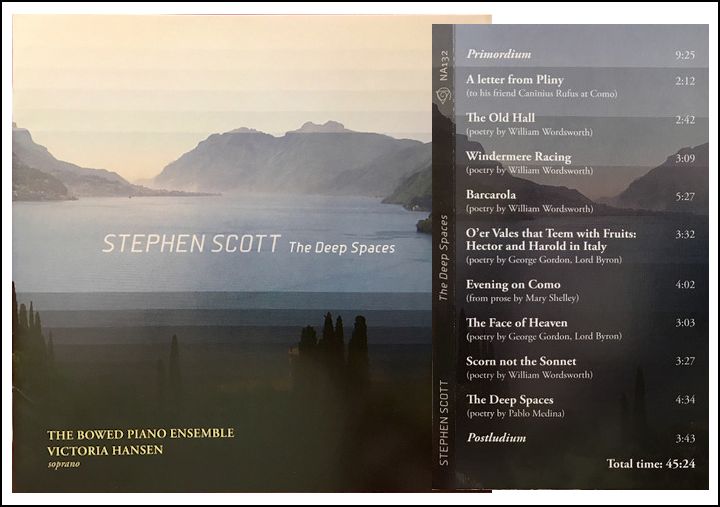

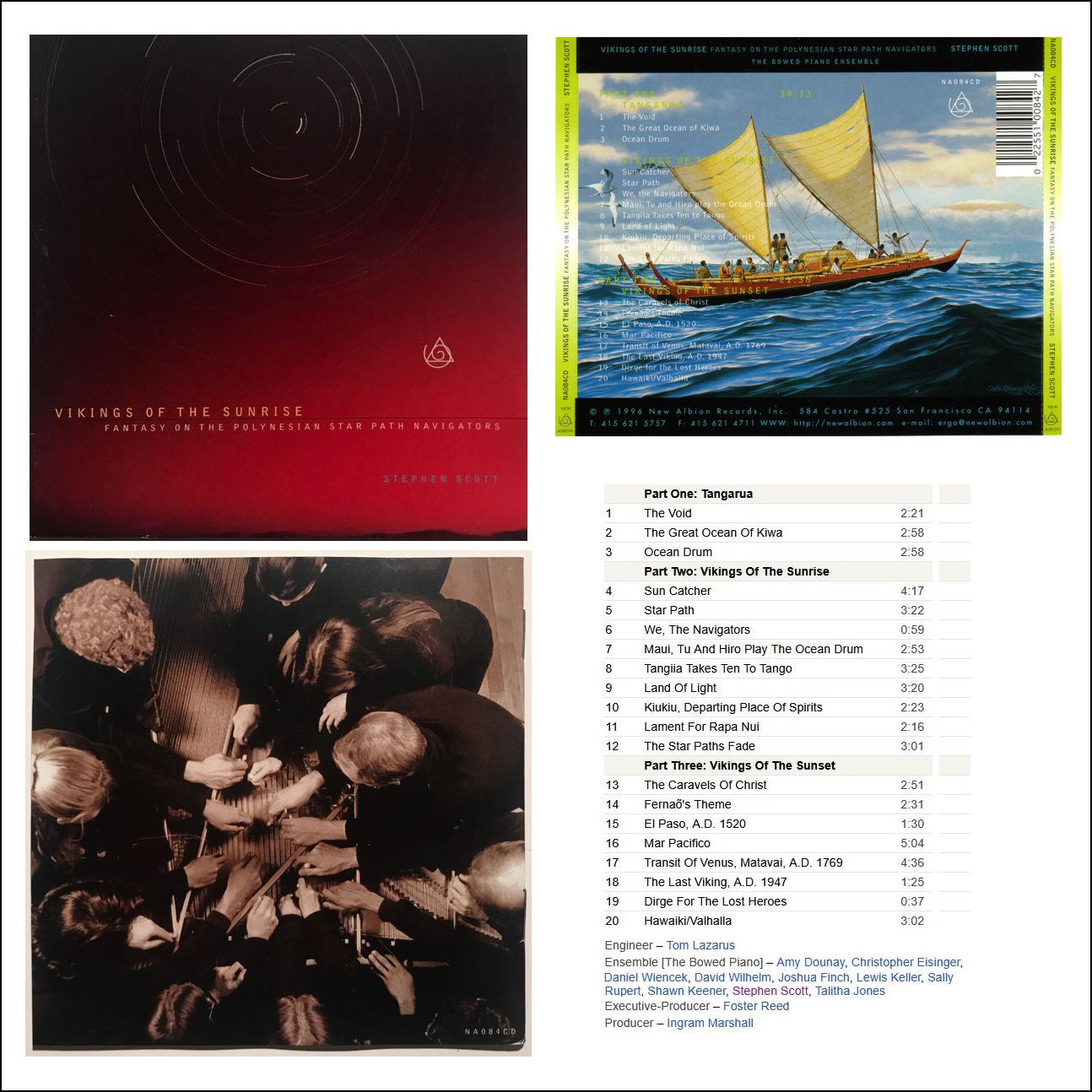

Stephen Scott (October 10, 1944 – March 10, 2021) was an American composer best known for his development of the bowed piano. This is a form of extended technique which involves a grand piano being played by an ensemble of ten musicians who utilize lengths of rosined horsehair, nylon filament, and other utensils to bow the strings of the piano, creating an orchestra-like sound. Scott borrowed the technique from C. Curtis-Smith, who invented it in 1972. Scott founded the Bowed Piano Ensemble in 1977, for which he composed. His work is associated with the minimalist style of composition. Scott studied with Homer Keller at the University of Oregon and subsequently with Ron Nelson and Gerald Shapiro. He taught music at Colorado College from 1969 to 2014, becoming a full professor there in 1989. He also taught at Evergreen State College and has served as visiting composer at the Aspen Music School, New England Conservatory of Music, Princeton University, the University of Southern California, and at several universities and conservatories in Australia and Europe. Several recordings with Scott's Bowed Piano Ensemble have been released by New Albion Records, Albany Records, and Navona Records. Scott has performed and composed pieces in a thirteen limit tuning by Terry Riley. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on March 19, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year; and on WNUR in 2006. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.