|

Andrea Silvestrelli is one of the most sought-after ‘bassi profondi’ on the international opera scene. Garnering critical acclaim for his debut at the Lyric Opera of Chicago in Rigoletto, the Chicago Sun-Times reported, “There were wild cheers for Andrea Silvestrelli …who brought a terrifying, sepulchral tone to the assassin Sparafucile.” The Chicago Tribune concurred, “Andrea Silvestrelli wielded a big, black, menacing bass in his debut as the assassin Sparafucile.” The current season opens with performances of Hagen in Götterdämmerung

in a return to the Taichung National Theater in Taiwan, followed by performances

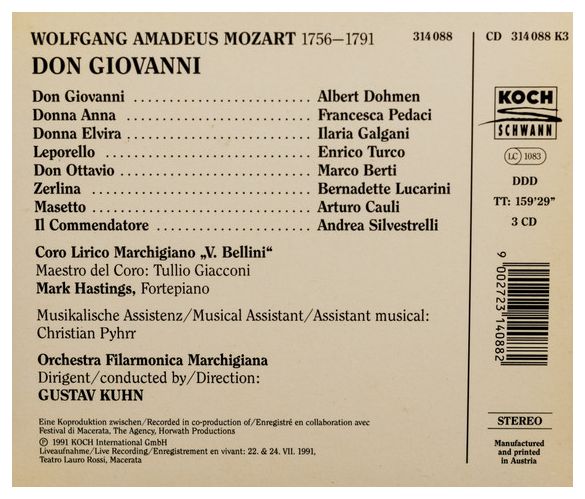

of the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlo with the Dallas Opera and Sparafucile

in Rigoletto with Opera San Antonio. Last season, he was Fafner in

Siegfried in Taiwan, and Geronte in Manon Lescaut and

Pistola in Falstaff with the Dallas Opera. In the 2017-2018 season,

Mr. Silvestrelli was heard as Hunding in Die Walküre in Taiwan,

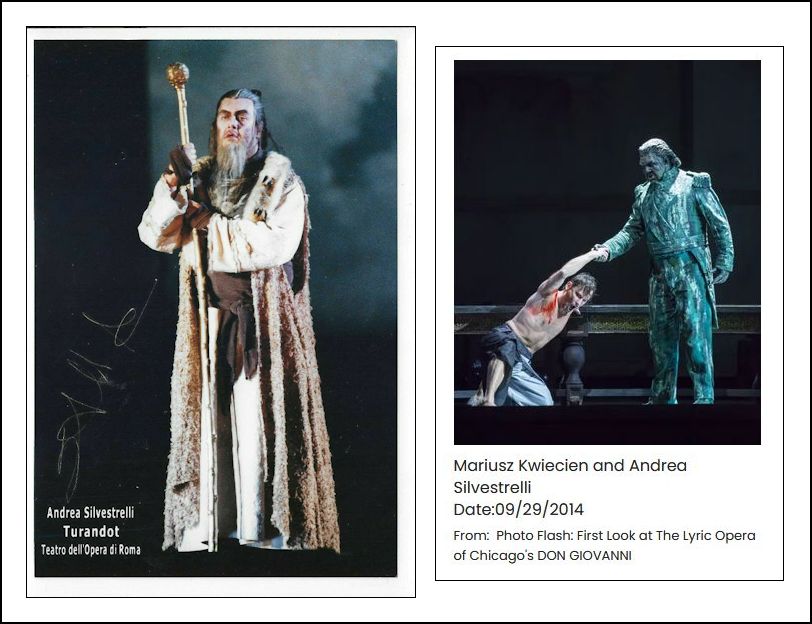

returned to Lyric Opera of Chicago as Nourabad in Les pêcheurs

de perles and Timur in Turandot, and sang the Grand Inquisitor

in Don Carlo with Washington National Opera. In spring 2018, he performed

in San Francisco Opera’s Ring Cycle as Fasolt in Das Rheingold

and Hagen in Götterdämmerung. [The photo below shows him

as Hagen in Brisbane, Australia.]

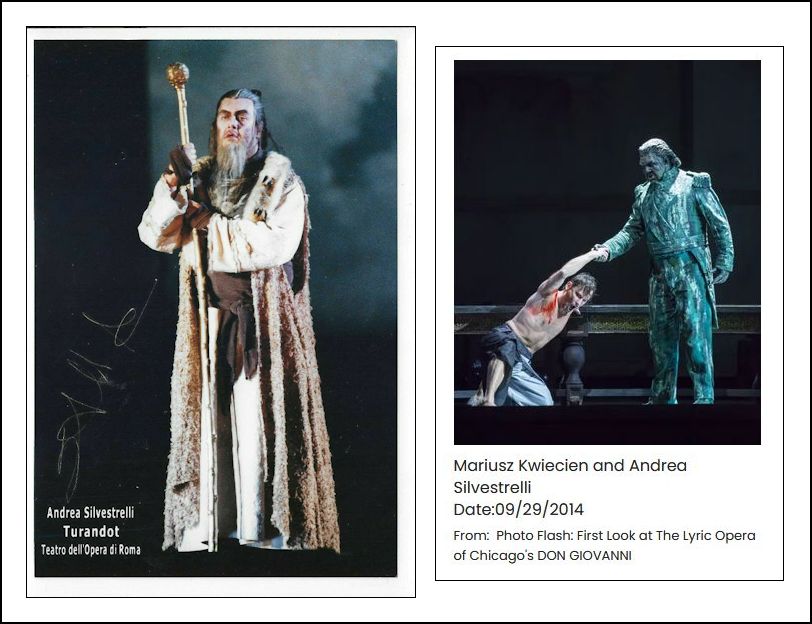

Mr. Silvestrelli’s performances in the 2016-2017 season included Fafner in Das Rheingold with National Taichung Theater, Oroveso in Norma with Lyric Opera of Chicago, Hagen in Götterdämmerung with Houston Grand Opera, and the Commendatore in Don Giovanni and Sparafucile in Rigoletto, both with San Francisco Opera. With SFO in 2015-2016, he sang the role of Wurm in Luisa Miller, The Night Watchman in Die Meistersinger von Nürnburg, Don Basilio in Il barbiere di Siviglia, and the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlo. He also returned to Erl, Austria for performances of the Ring Cycle at the Tiroler Festspiele. == Text in this box is mostly taken from the

Opera Festival of Chicago website.

Photo is from another source. |

© 2000 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on November 10, 2000. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few weeks later. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to Marina Vecci, Production Administrator with Lyric Opera of Chicago for providing the translation. My thanks also to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.