|

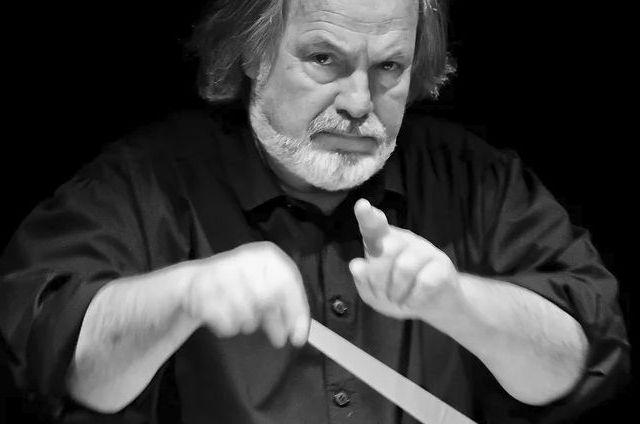

Born

August 25, 1945 in Turrach in Styria, Gustav Kuhn studied conducting

with Hans Swarowsky, Bruno Maderna, and Herbert von Karajan at the

conservatories in Vienna and Salzburg. He graduated from Salzburg

University in philosophy, psychology, and psychopathology. Kuhn was

only 24 years old when he won the prestigious international conducting

competition of the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF). From 1970

to 1977, Kuhn workd as chorus director and conductor at the Istanbul

Opera House, then as first Kapellmeister at the Dortmund Opera House.

During this time, he gave guest performances in Palermo, Naples, and

Bologna. Later he had engagements as guest conductor in Rome, Florence,

Venice, and Zurich. He conducted the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, the

Staatskapelle Dresden, the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, the London

Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic

Orchestra, the Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala in Milan, the Orchestre

National de France in Paris, the Academia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia

in Rome, the NHK Orchestra in Tokyo, and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. In 1974, Kuhn founded the

Institute for Aleatoric Music in Salzburg. In 1977, he made his debut at

the Vienna State Opera conducting Richard Strauss’ Elektra. Only

a year later, in 1978, he made his debut at the Bavarian State Opera and

the Salzburg Festival. The following season Maestro Kuhn made his conducting

debut at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden in London and was engaged as

General Music Director in Berne. In 1980, Kuhn conducted the opening production

at the Glyndebourne Festival. More debuts followed in 1981 conducting Fidelio

in Chicago, 1982 Così fan tutte at the Paris Opera,

1984 Tannhäuser at Milan’s Scala, 1986 Un ballo

in maschera at Arena di Verona. In 1986 Gustav Kuhn started

to direct and produce operas so as to achieve a greater artistic

union between a work’s visual and musical components. Kuhn produced

and staged The Flying Dutchman (Trieste), Parsifal

and La Bohème (Naples), Don Carlo (Torino),

Mozart’s Da Ponte operas (Festival di Macerata), Rossini’s Otello

(Berlin, Braunschweig and Tokyo), La Bohème,

Falstaff and La Traviata (Tokyo), Capriccio

(Milan), among others. After making his debut as

an opera director with his staging of The Flying Dutchman in Trieste

(set design and costumes: Peter Pabst), he developed the “Hall

Opera” series for Suntory Hall Opera in Tokyo (1993). Kuhn conducted

at the Salzburg Festival until 1997 (1978 debut, 1980 Figaro,

1989 Un ballo in maschera, 1992, 1994 and 1997 La clemenza

di Tito). From 1983 to 1985, Kuhn served as general music director

at the Bonn Opera, which was followed by engagements as principal conductor

of the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome and later as artistic director of

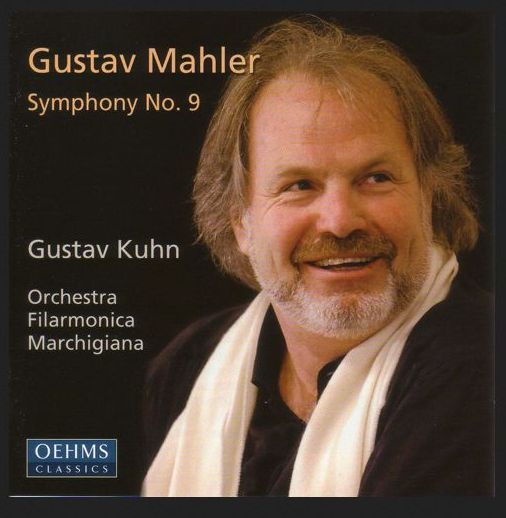

the Teatro di San Carlo in Naples. Kuhn headed the music festival in

Macerata from 1990 to 1994; from 1994 he served as artistic director

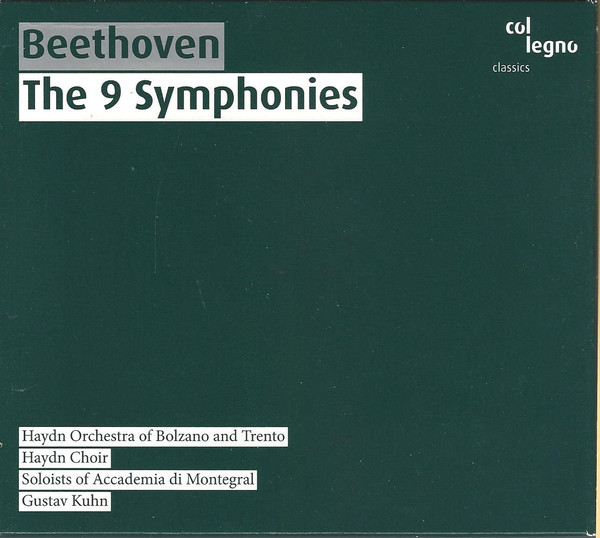

of the Filarmonica Marchigiana, Ancona (1997-2002). Kuhn was artistic

director of the Haydn Orchestra of Bolzano and Trento from January 2003

until December 2012. In October 2013 Kuhn conducted two performances

of Wagner’s Parsifal in Beijing. This was a very special occasion

because Wagner’s opera had never been performed before in China. Gustav Kuhn has been artistic

director of Neue Stimmen (New Voices), an international singing

competition organized by the German Bertelsmann Foundation in Gütersloh,

since 1987. In 1992 Kuhn founded the Accademia di Montegral, based

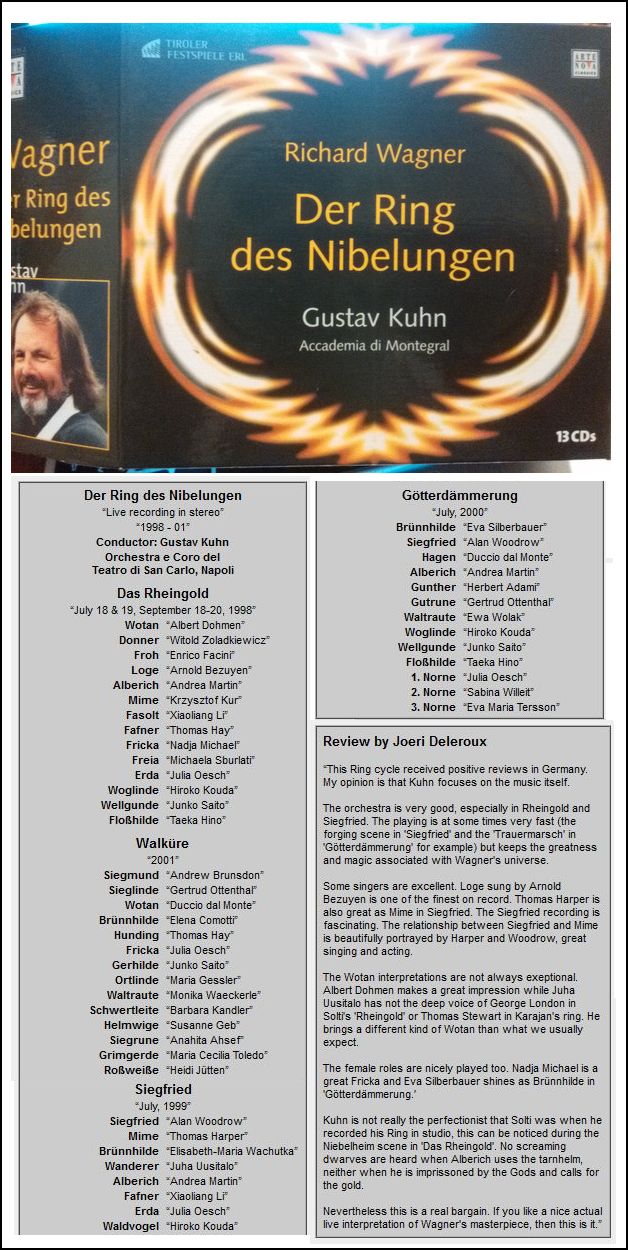

at the Convento dell’Angelo in Lucca (Tuscany) in 2000. In 1997, Kuhn

founded the Tyrol Festival Erl. After working on Wagner’s Ring

for several years, Kuhn took the production on tour for the first time

in 2005 (Santander) and produced the now legendary 24-hour “Ring”.

The same year Dr. Hans Peter Haselsteiner agreed to become president

of the Tyrol Festival Erl. The construction of the new Festspielhaus,

which was opened on 26th December 2012, was made possible by Mr. Haselsteiner’s

efforts and commitment. In addition to its summer

festival, the Tyrol Festival Erl now also hosts a winter Festival that

runs annually from 26th December to 6th January, and Kuhn is the general

artistic director. The new winter program focuses on works from the Italian

and the bel canto repertoire as well as Mozart operas. In the summer the

old Passionsspielhaus continues to be an important performance venue for

the Festival’s Wagner and Strauss productions. With the performance of

Lohengrin in July 2012, Kuhn brought his cycle of Wagner’s

ten greatest operas at Erl’s Festspielhaus to a close. Gustav Kuhn’s compositions include orchestral works, masses and solo pieces; his instrumentation of Janáček’s Diary of One Who Disappeared met with great acclaim at the Opéra National de Paris (released by Edition Peters). From 2007 to 2011 Maestro Kuhn performed a series of classical concerts entitled Delirium in his former hometown of Salzburg. His recordings are available on the labels col legno, BMG, EMI, CBS, Capriccio, Supraphon, Orfeo, Koch / Schwann, Coreolan, ARTE NOVA and others. His book Aus Liebe zur Musik (Out Of Love for Music) was published by Henschel. |

|

Gustav Kuhn at Glyndebourne

[Selfishly, I have only listed artists whom I have interviewed. BD] 1980 & 1983- Die Entführung aus dem Serail with Valerie Masterson (1980) as Constanze; Gösta Winbergh (1980) Ryland Davies (1983) as Belmonte 1981 & 1984 - Marriage of Figaro [Peter Hall producer] with Felicity Lott (1981) as Countess; Alan Titus (1981) as Count; Faith Esham (1984) as Susanna Ugo Benelli (1984) as Don Basilio; Mimi Lerner (1984)

as Marcellina

1981 - Ariadne auf Naxos [John Cox producer] with

Gianna Rolandi

as Zerbinetta; Dennis Bailey as Bacchus; Dale Duesing as Harlekin[One performance at Glyndebourne, and one performance

at Royal Albert Hall, London]

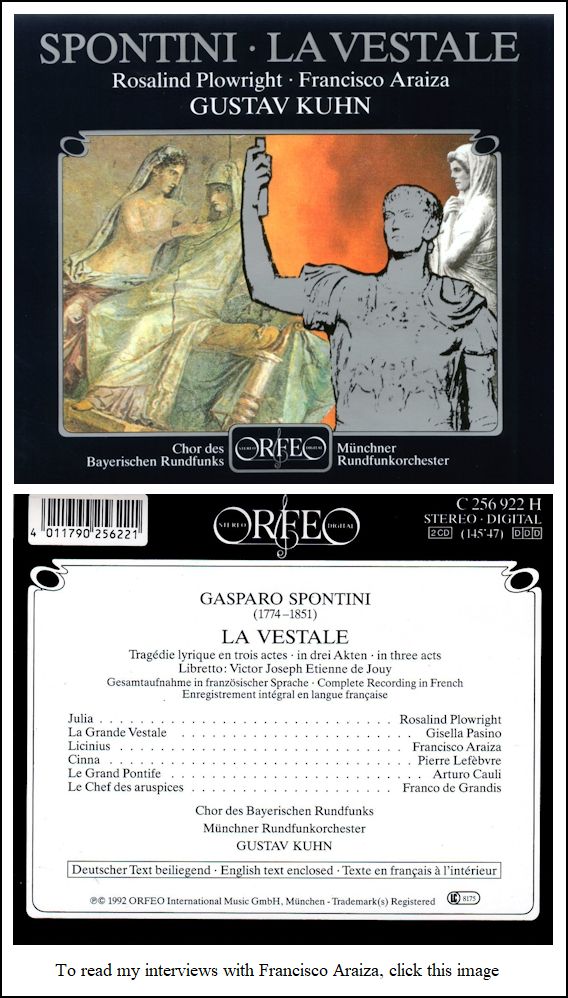

1983 - Intermezzo [John Cox producer] with Felicity Lott as

Christine [DVD shown above-right]1984 - Così fan tutte [Peter Hall producer] with Carol Vaness as Fiordiligi; Delores Ziegler as Dorabella, Ryland Davies as Ferrando; J. Patrick Raftery as Guglielmo; Claudio Desderi as Don Alfonso

|

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at the conductors apartment on November 19, 1981. Portions were broadcast on WNIB ten years later, and again in 1997. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.