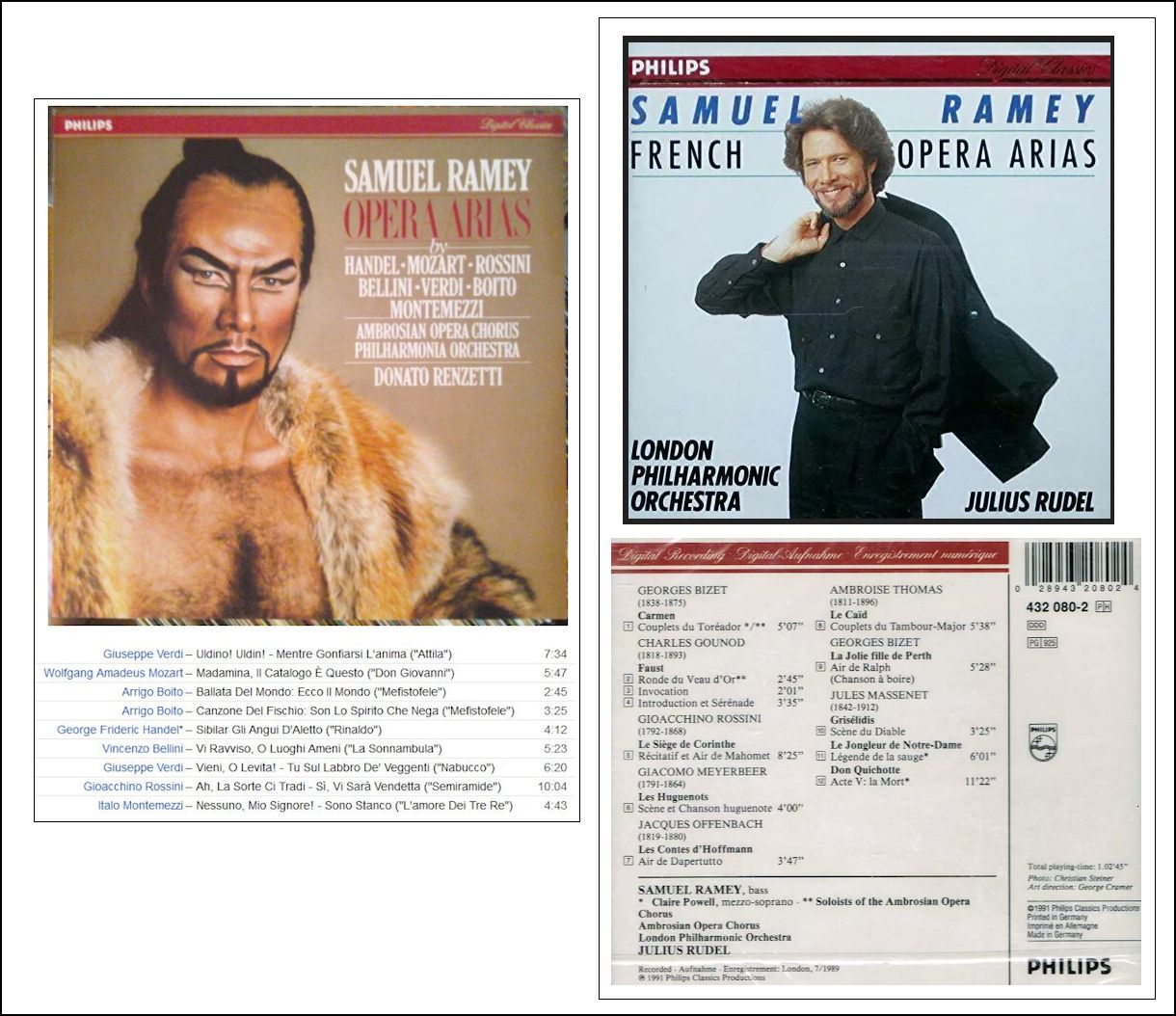

See my interviews with Donato Renzetti, and Julius Rudel

|

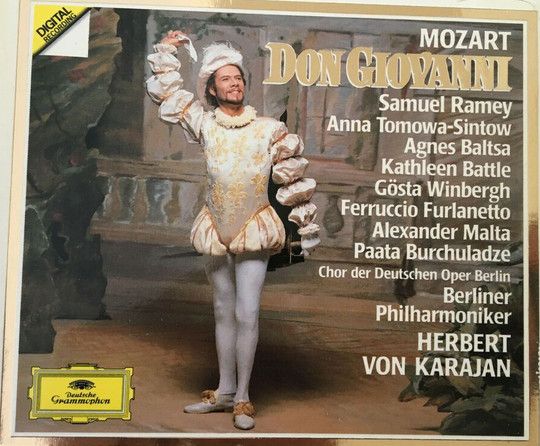

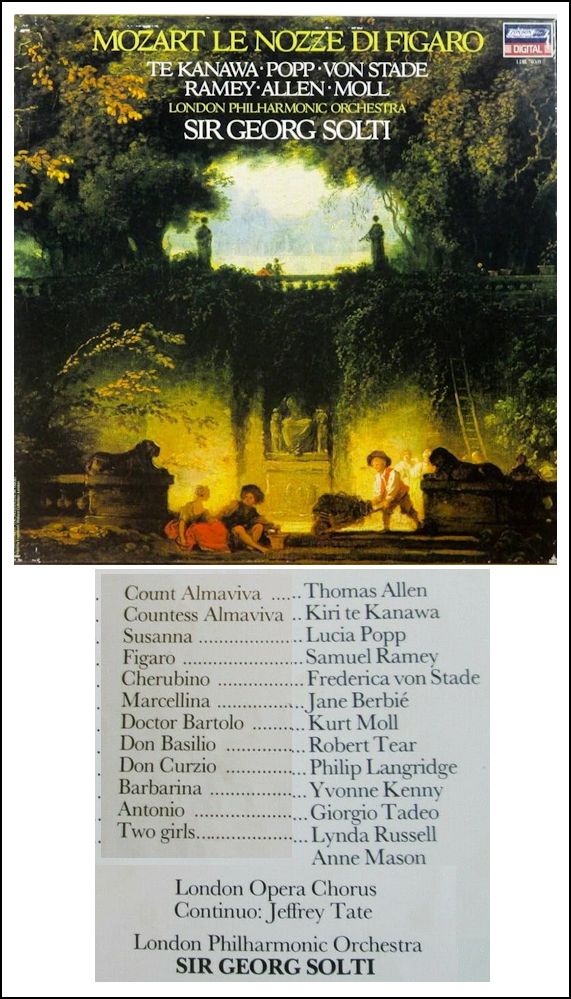

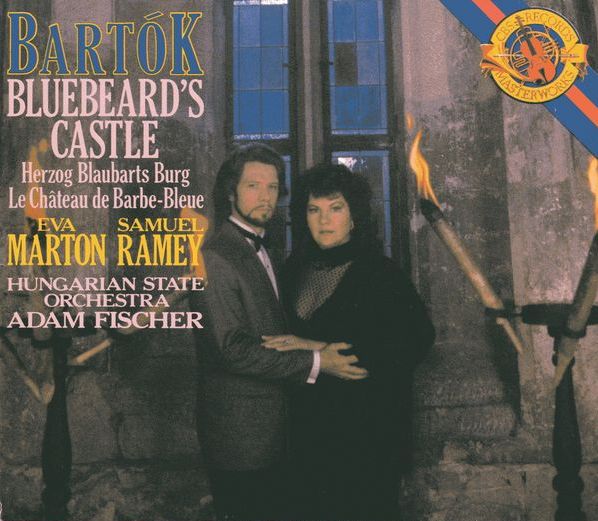

For almost three decades, Samuel Ramey (born March 28, 1942) has reigned as one of the music world’s foremost interpreters of bass and bass-baritone operatic and concert repertoire. With astounding versatility, he commands an impressive breadth of repertoire encompassing virtually every musical style from the fioritura of Argante in Handel’s Rinaldo, which was the vehicle of his acclaimed Metropolitan Opera debut in 1984, to the dramatic proclamations of the title role in Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle, which he sang in a new production at the Metropolitan Opera televised by PBS. Mr. Ramey’s interpretations embrace the bel canto of Bellini, Rossini, and Donizetti, the lyric and dramatic roles of Mozart and Verdi, and the heroic roles of the Russian and French repertoire. Ramey continues to perform at the world’s most important opera houses and concert stages. He returned to the Metropolitan Opera as Timur in Franco Zeffirelli’s production of Turandot. Further performances included a revival of Duke Bluebeard in Bluebeard’s Castle, and his debut as Sarastro in The Magic Flute. Other engagements included Don Basilio in Il Barbiere di Siviglia, Rambaldo in La Rondine, Claudius in Hamlet with Washington National Opera, Scarpia in Tosca at Deutsche Oper Berlin, Méphistophélès in Nice; the Grand Inquisitore in Don Carlos with Houston Grand Opera, and Benoit/Alcindoro at The Dallas Opera.

[Vis-à-vis the recording shown at left, see my interviews

with Jerry Hadley,

Cecilia Gasdia,

Susanne Mentzer,

Alexandru Agache,

Brigitte

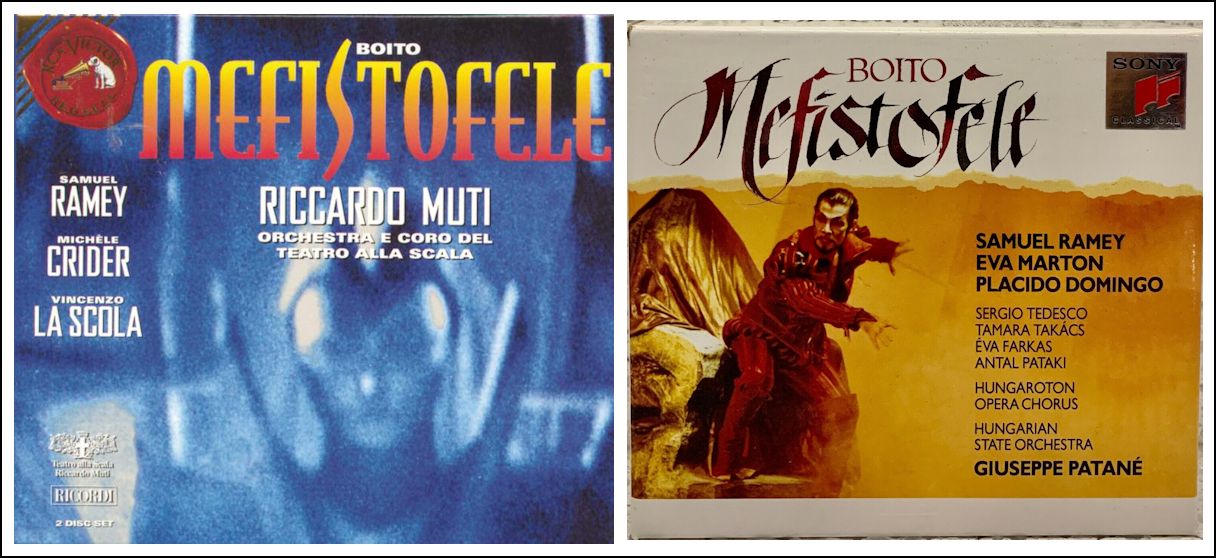

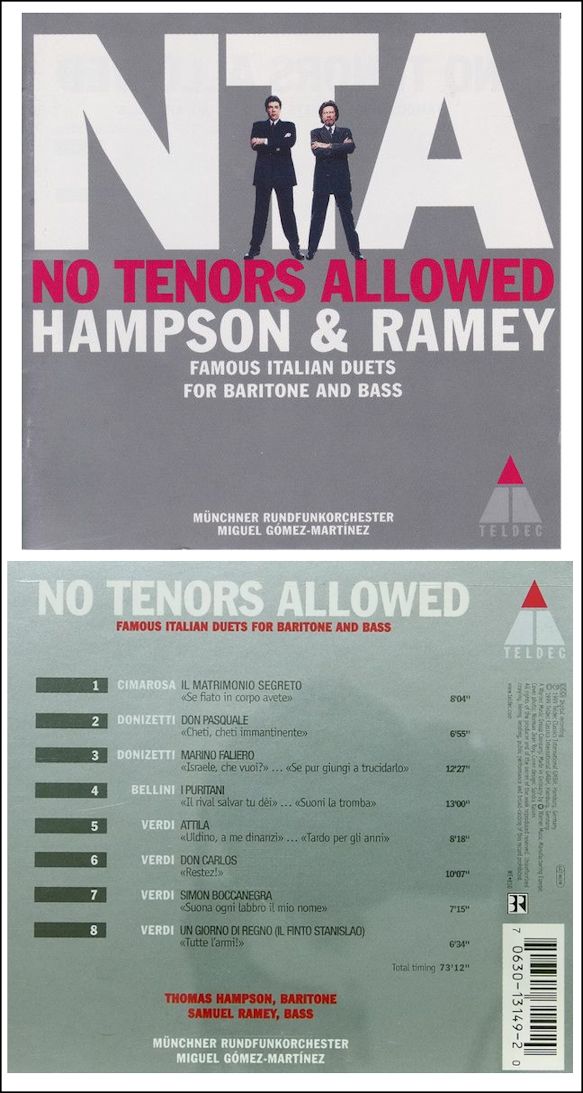

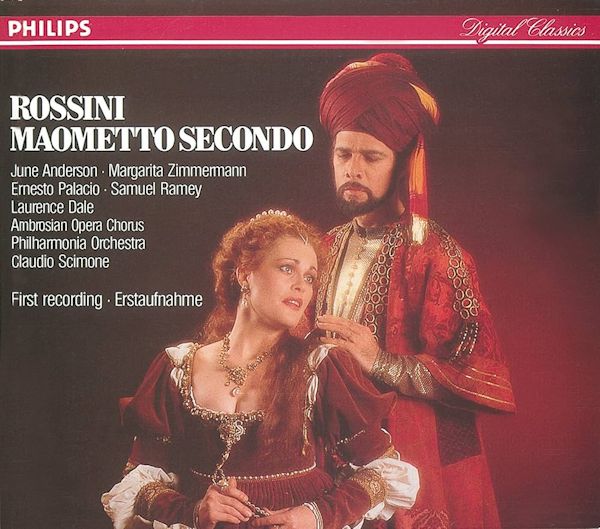

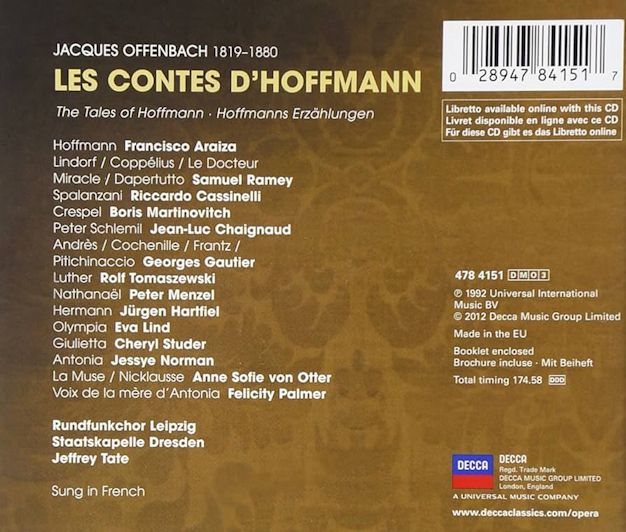

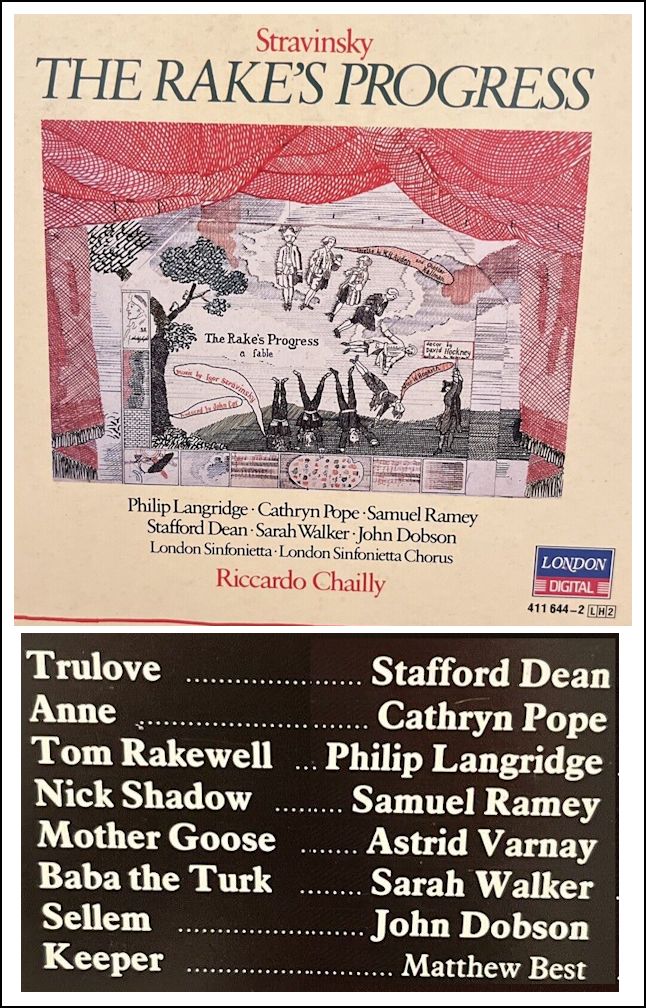

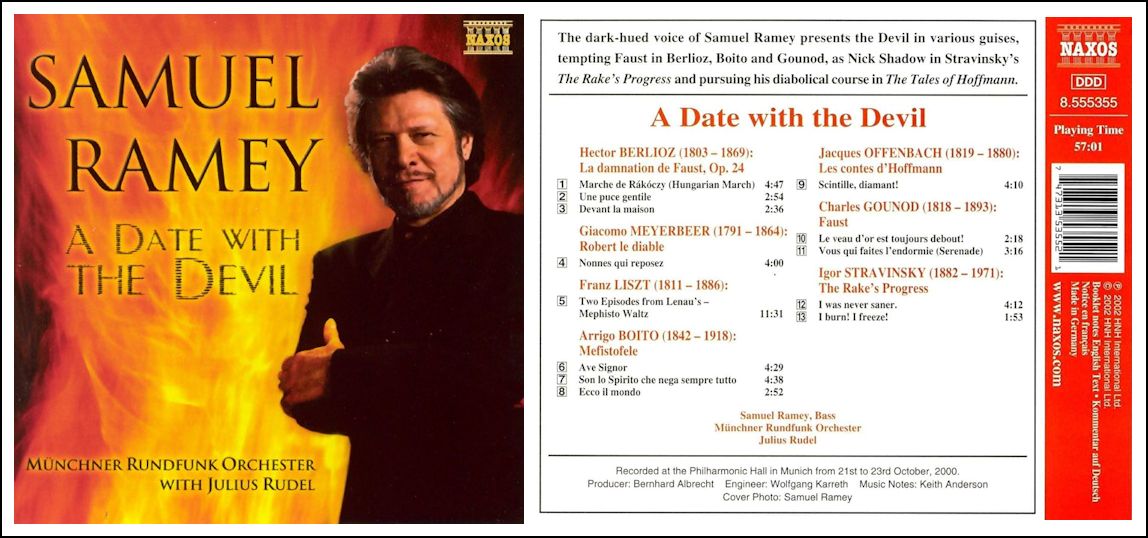

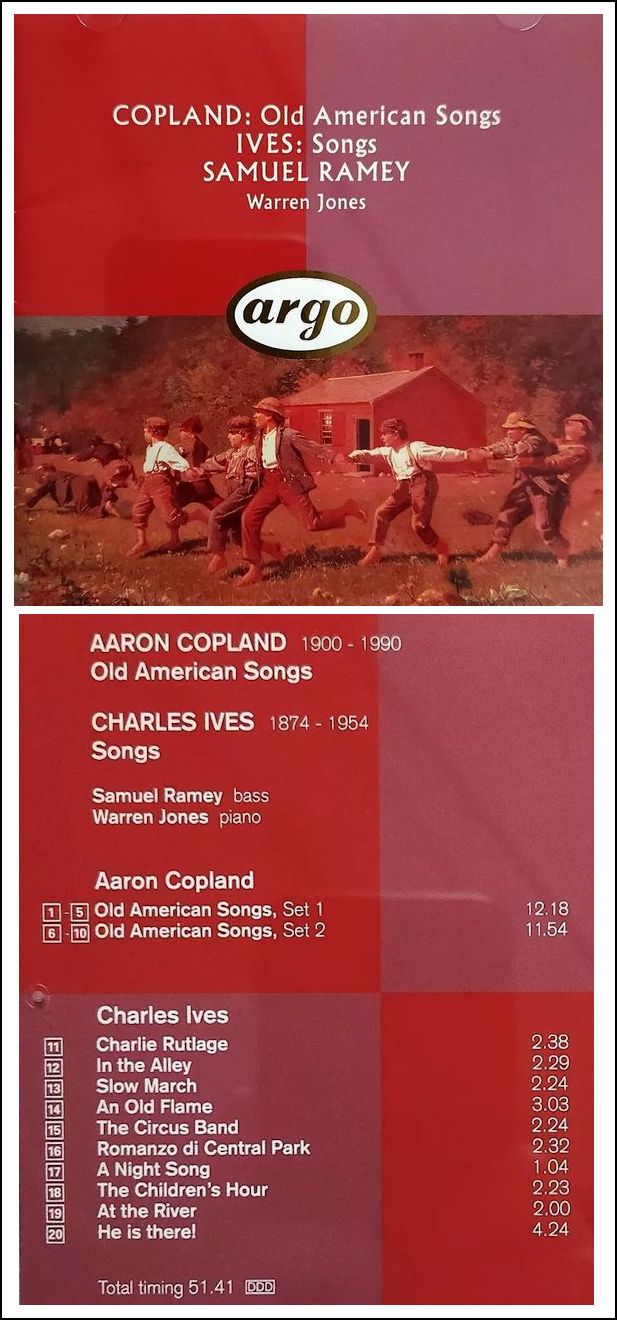

Fassbaender, and Carlo Rizzi.] The unique expressiveness of the bass voice has inspired many composers to assign them the portrayal of devils and villains, and it is in this repertoire that Ramey has established a reputation unequaled in the musical world. Méphistophélès in Gounod’s Faust has become his most-performed role with over 200 performances in more than twenty productions, as well as the recording shown at left. He is equally well-known in opera houses and concert halls throughout the world for his performances of Boito’s Mefistofele, including over 70 performances in the Robert Carsen production of this work specifically created for Ramey. He has recorded the Boito opera twice, as shown just below this box. Other devils include Berlioz’ in La damnation de Faust, the sinister Nick Shadow in Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, and the tour de force of all four villains in Offenbach’s Les contes d’Hoffmann. In 1996 Ramey presented a sold-out concert at New York’s Avery Fisher Hall titled A Date with the Devil, in which he sang fourteen arias representing the core of this repertoire, and he continues to tour this program throughout the world. In 2000 Ramey presented this concert at Munich’s Gasteig Concert Hall, which was recorded live by Naxos Records and was released on compact disc in the summer of 2002. Ramey’s unique talents have afforded the world’s leading theaters an opportunity to expand their repertoire and present works such as Verdi’s Attila, Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, Montemezzi’s L’amore dei tre re, Rossini’s Maometto II, and Massenet’s Don Quichotte. His repertoire of more than fifty roles also encompasses the more standard repertoire. He has appeared on the stages of the Metropolitan Opera, Teatro alla Scala, Royal Opera, Covent Garden, Vienna Staatsoper, Opéra de Paris, Arena di Verona, Deutsche Oper Berlin, San Francisco Opera, Lyric Opera of Chicago, Houston Grand Opera, Teatro la Fenice, Teatro Colon, and the operas of Munich, Hamburg, Geneva, Florence, Zürich and Amsterdam, among others. In concert, he has performed with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, New York Philharmonic, Berlin Philharmonic, Vienna Philharmonic, La Scala Orchestra, National Symphony Orchestra, and the symphonies of Chicago, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and San Francisco. [A complete listing of his Chicago appearances is shown in the box at the bottom of this webpage.] Throughout his career, Mr. Ramey has worked with every major conductor including Claudio Abbado, Leonard Bernstein, James Conlon, Sir Colin Davis, Valery Gergiev, Bernard Haitink, James Levine, Lorin Maazel, Riccardo Muti, Kent Nagano, Seiji Ozawa, Sir Simon Rattle, Julius Rudel, Sir Georg Solti, and Herbert von Karajan. Ramey holds the distinction of being the most recorded bass in history. His more than eighty recordings include complete operas, recordings of arias, symphonic works, solo recital programs, and popular crossover albums on several major labels. His recordings have garnered nearly every major award including three Grammy Awards, Gran Prix du Disc Awards, and “Best of the Year” citations from journals including Stereo Review and Opera News. His exposure on television and video is no less impressive, with video recordings of the Metropolitan Opera’s Don Giovanni, Carmen, Bluebeard’s Castle, Semiramide, Nabucco, I Lombardi, and the compilation “The Met Celebrates Verdi;” San Francisco Opera’s Mefistofele; The Rake’s Progress from the Glyndebourne Festival; Attila and Don Carlo from La Scala; and the Salzburg Festival’s Don Giovanni. A native of Colby, Kansas, Samuel Ramey was active in music throughout high school and college. In 1995 he was named “Kansan of the Year,” and in 1998 the French Ministry of Culture awarded him the rank of Commander in the Order of Arts and Letters. He formerly served as a member of the faculty at Roosevelt University’s Chicago College of Performing Arts, and is a Distinguished Professor of Opera at Wichita State University's School of Music.

== Text of biography (slightly edited) is mostly

from the agent’s website.

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. == Note that links are only shown at the first appearance of the artist’s name, even though they appear again later. == Ramey made many recordings, and just a few appropriate ones are shown on this webpage. BD |

| In a talk given

at Yale in January of 1961, Chaliapin’s daughter

spoke about his interpretations. The Yale Daily News reported

on the event. “Another aspect of [her father’s] career was his three

different interpretations of the devil. In Gounod’s

Faust, the Devil must be evil. He must be conniving

and shrewd. Then in Mefistofele she described her father

as the violent Devil of hatred. Here is evil which leads to killing

and wars. But in The Demon, Chaliapin becomes the sorrowful

banished spirit. This demon is not a Devil, he is a defeated angel,

a Lucifer.” As has been noted, Ramey included several versions of the Devil in his repertoire, and eventually combined all of them into a concert and recording, which is shown below.

|

Samuel Ramey

at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1979 La Bohème (Colline) - with Mitchell/Soviero/Niculescu, Shicoff/Prior/Moldoveanu, Romero, Zilio, Nolen/Stone, Tajo; Chailly/Schaenen, Frisell, Pizzi 1984 Rinaldo [In concert] (Argante) - with Horne, Valente, Vaness, Raffanti, Doss, Cowan; Bernardi 1987-88 Faust (Méphistophélès) - with Shicoff, Gustafson/Soviero, Raftery, White, J.H. Murray, Vozza; Fournet, Diaz, Samaritani, Tallchief Marriage of Figaro (Figaro) - with Ewing, Raimondi, Lott, von Stade, Korn, Benelli, Adams; Davis, Hall, 1988-89 Don Giovanni (Giovanni) - with Vaness, Desderi, Mattila, McLaughlin, Winbergh, Macurdy, Cowan; Bychkov, Ponnelle 1989-90 Don Carlo (Philip II) - with Te Kanawa, Rosenshein, Hynninen, Troyanos, Ryhänen, Runey; Conlon, Frisell 1991-92 Mefistofele (Mefistofele) - with Jóhannsson/Cupido, Millo, Johnson, Maultsby, Sandra Walker, Fowler, Denniston; Bartoletti, Carsen Marriage of Figaro (Figaro) - with McLaughlin/Hall, Schimmel, Lott, Mentzer/von Stade, Loup, Palmer, Benelli, P. Kraus, Futral; Davis, Hall 1993-94 Don Quichotte (Quichotte) - with Lafont, Mentzer, Perkins; Nelson, Koenig, Samaritani, Schuler, D. Palumbo, Dufford Susannah (Blitch) - with Fleming, Magee, Kraft, P. Kraus; Manahan, Falls, Yeargan, Schuler, D. Palumbo, Dufford 1994-95 [Opening Night] Boris Godunov (Boris) - with Denniston, Kavrakos, Ognovenko, Jones, Shields, Gordon; Bartoletti, Winge, Wassberg Rake's Progress (Nick Shadow) - with Swenson, Hadley, Bean, Palmer; Davies, Vick, Hudson 1995-96 Faust (Méphistophélès) - with Leech, Fleming/Rambaldi/Magee, Hvorostovsky, Christin; Nelson, Corsaro, Calavecchia, Tallchief 1996-97 [Opening Night] Don Carlo (Philip II) - with Vaness, Sylvester, Chernov, Zajick, Halfvarson, Tian; Gatti/Fagen, Frisell, Quaranta 1997-98 [Opening Night] Nabucco (Zaccaria) - with Agache, Gulighina, Denniston, Redmon, Aceto; Bartoletti, Moshinsky, Yeargan 1998-99 Mefistofele (Mefistofele) - with Margison, Dessì/Byrne, Christin, Raven; Rath, Carsen, McClintock 1999-2000 A Date with the Devil [Concert] - with Davis 2000-01 Attila (Attila) - with Gruber, Michaels-Moore, Thompson/Smith, Vipulis; Johnson/R. Palumbo, Moshinsky/Edwards, Yeargan 2001-01 Billy Budd (Claggart) - with Gunn, Begley, Stilwell, P. Kraus, Langan, Cangelosi; Davis, McVickar, Edwards 2002-03 Susannah (Blitch) - with Radvanovsky, Griffey, Wood, Cangelosi; Rudel, Falls/Nuckton, Yeargan 2003-04 Faust (Méphistophélès) - with Haddock, Racette/Wall, Torre, McNeese, Christin; Elder, Corsaro, Perdziola 2004-05 Tosca (Scarpia) - with Dimitriu/Millo, Shicoff/Ventre, Tigges, Travis, Cangelosi; Bartoletti, Cox, Mongiardino Samuel Ramey with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

and Chorus

[Chorus Master: Margaret Hillis] March, 1981 Te Deum (Bruckner) - with Norman, Minton, Rendell; Barenboim [Recorded and issued by DG (with Symphony #1, and later Symphony #8)] November, 1984 Boris Godunov [Original Version] (Pimen) - with Raimondi, Valentini-Terrani, Kaludov, Langridge, Welker, Shirley-Quirk, Kaasch; Abbado November 16, 1986 Requiem (Verdi) - with M. Price, Finney, Cole; Abbado June 23, 1989 [Ravinia Festival] Requiem (Verdi) - with Gruber, Troyanos, Lakes; Levine November 6, 1990 [Centennial Gala] Ode to Joy (Finale of Beethoven Symphony #9) - with McNair, Mentzer, Lakes; Solti [Photo] July 8, 2000 [Ravinia Festival] Selections by Copland, Leigh, Loewe, Mozart, Rodgers, and Verdi - with von Stade; Miguel-Harth Bedoya July 2, 2005 [Ravinia Festival] Chansons de Don Quichotte (Ibert) & Don Quichotte à Dulcinée (Ravel) - with Conlon August, 2008 [Ravinia Festival] Don Giovanni (Leporello) - with D'Arcangelo, Dehn, Isokoski, Murphy, Spence; Conlon, Apollo Chorus/Alltop [The Chicago Tribune review mentions Ramey’s Leporello as being a new role for local fans to enjoy. A 2015 photo of Ramey in another ‘second’ role, as the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlo, appears at the bottom of my interview with William Powers, who was singing Philip II, a previously favorite role of Ramey.] Samuel Ramey with the Chicago Opera Theater

Ramey has also performed in several of the benefit concerts for the Over the Rainbow Association at Pick-Staiger concert hall on the campus of Northwestern University, along with Nancy Gustafson, Richard Leech, Denyce Graves, Sylvia McNair, Bo Skovhus, Jennifer Larmore, and others. |

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 22, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1990, 1991, and 1997. This transcription was made in 2024, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.