|

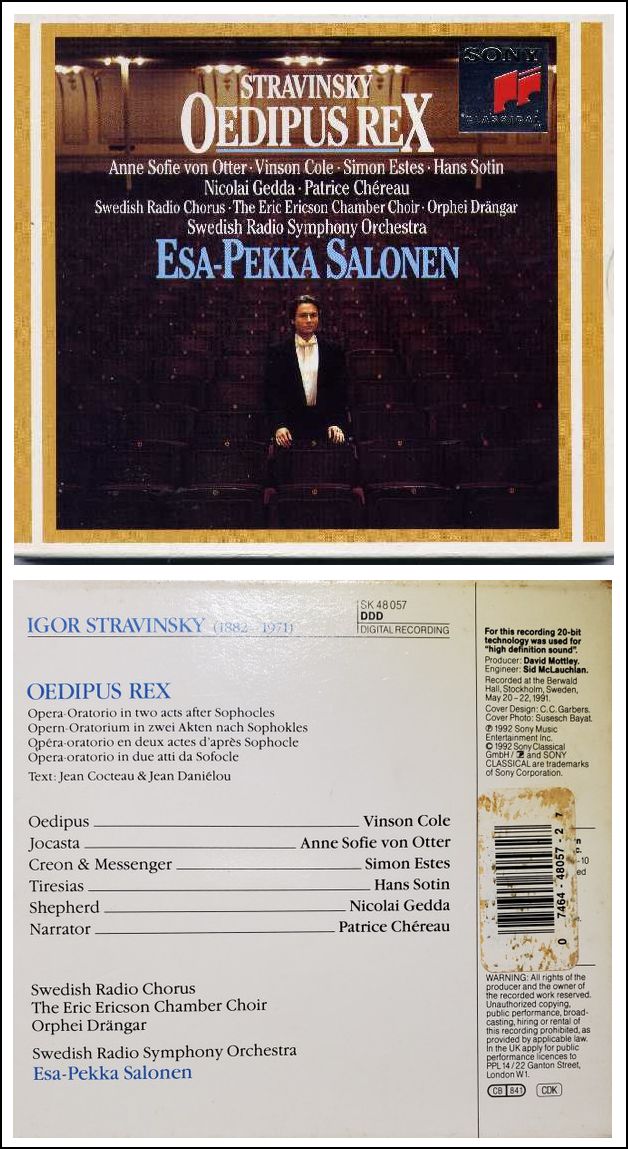

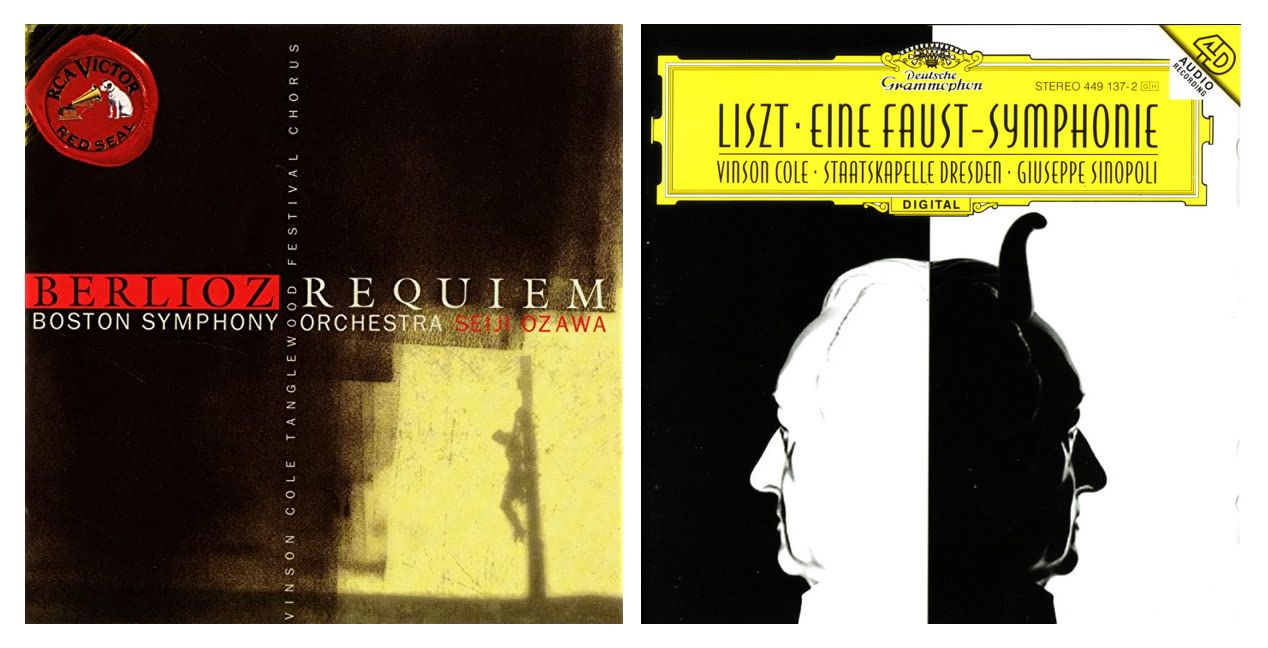

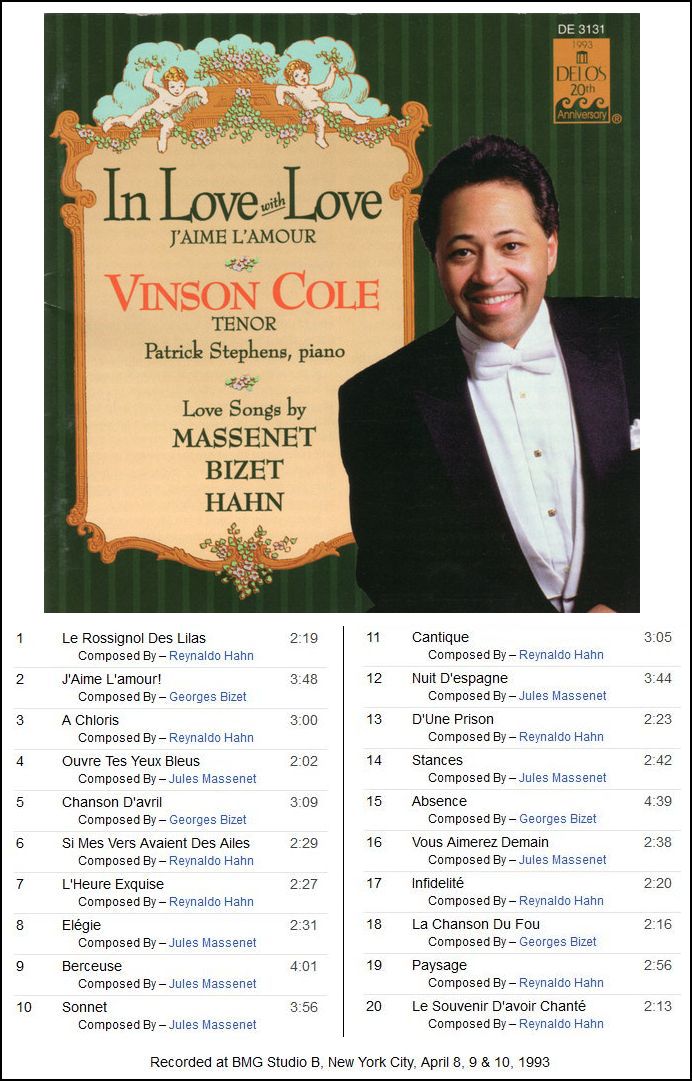

American tenor Vinson Cole is internationally recognized as one of

the leading artists of his generation. His career has taken him to all

of the major opera houses across the globe including the Metropolitan Opera,

Opera National de Paris Bastille, Teatro alla Scala Milan, Theatre Royale

de la Monnaie, Brussels, Berlin State Opera and the Deutsche Oper Berlin,

Munich State Opera, San Francisco Opera, Hamburg State Opera, Opera

Australia and the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Seattle Opera and

many more. Equally celebrated for his concert appearances, Mr. Cole has

been a frequent guest of the most prestigious orchestras throughout the

world and has collaborated with the greatest conductors of this era including

Christoph

Eschenbach, Claudio

Abbado, Carlo Maria Giulini, James Levine,

Lorin Maazel,

James Conlon,

Kurt Masur, Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti,

Seiji Ozawa, Gerard Schwarz,

Sir Georg Solti

and Giuseppe Sinopoli.

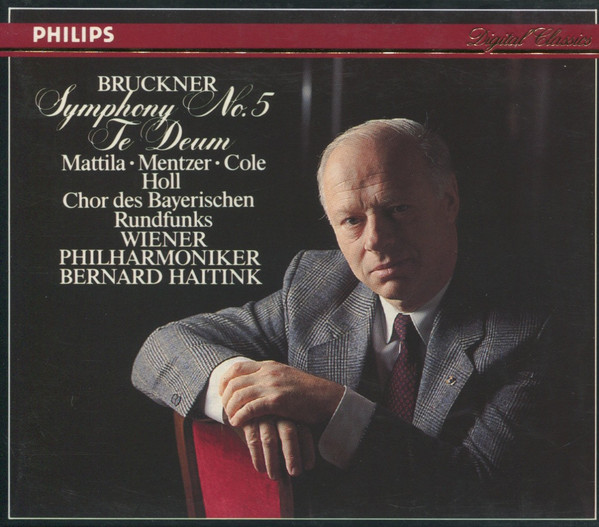

Mr. Cole had an especially close working relationship with Herbert

von Karajan, who brought the artist to the Salzburg Festival to sing

the Italian Tenor in Der Rosenkavalier – the first of many performances

there together. Their collaboration went on to include works such as Verdi’s

Requiem, Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis. Mozart’s

Requiem, Bruckner’s Te Deum. Many of these

were issued on recordings on Deutsche Grammaphon. He was the performer

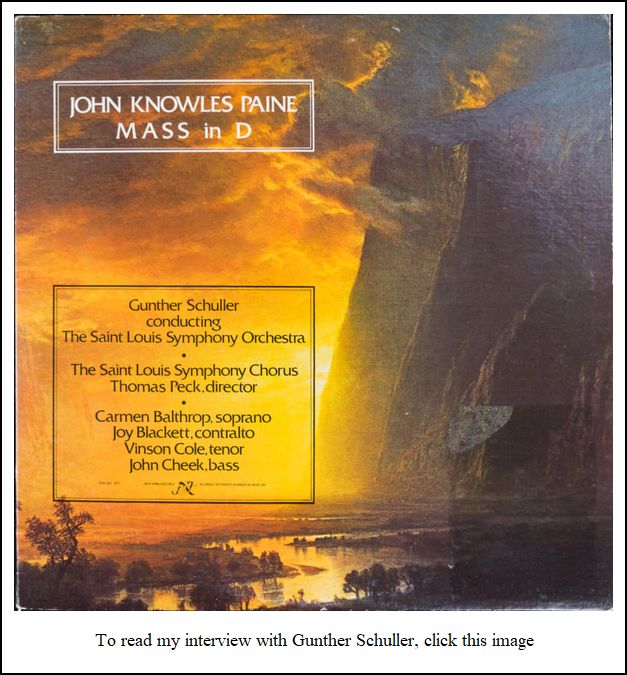

on the soundtrack for the film Immortal Beloved. As a teacher, American tenor Vinson Cole has taught at the University of Washington School of Music, the New England Conservatory of Music, the Cleveland Institute of Music, the Aspen Music Festival and School, Glimmerglass Opera, and the Santa Fe Opera. He has conducted master classes for San Francisco Opera’s Merola Program and the Canadian Opera Company. Currently, Cole is a faculty member at the Conservatory of Music and Dance at the University of Missouri, Kansas City. Vinson Cole, born in Kansas City, studied at the University of

Missouri, Kansas City before attending the Philadelphia Musical Academy

and the Curtis Institute of Music. In 1977, Cole won the Metropolitan Opera

Auditions, the WGN Competition, and was awarded both the Rockefeller Foundation

and the National Opera Institute grants. Cole’s career took off from there

as he went on to perform principal roles with the Metropolitan Opera, San

Francisco Opera, Opèra National de Paris, Paris Opera-Bastille, Teatro

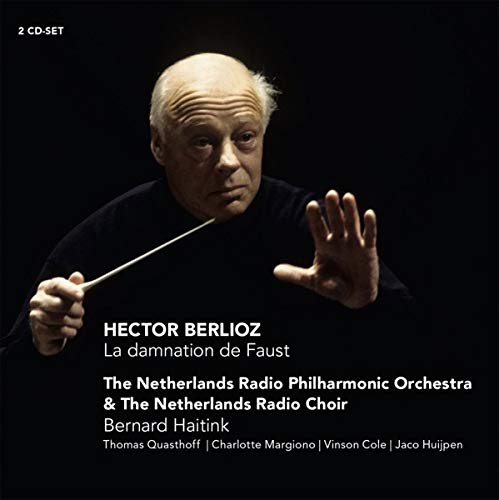

alla Scala, and many more. Cole became well known for his interpretation

of French repertoire after singing in the Manon centennial performances

with Paris’s Opera Comique in 1984. Since then, he has performed singular

interpretations of roles in such operas as Lakmè, Carmen,

Don Carlos, and Faust. He has been honored with

numerous awards including special invitations to perform with the Harriman-Jewell

Series recitals and received an honorary doctorate from William Jewell

College. He also received the Alumni Award from the Conservatory at

UMKC, plus the Seattle Mayor’s Arts Award for outstanding individual

achievement and commitment to the arts. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 24, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2000. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.