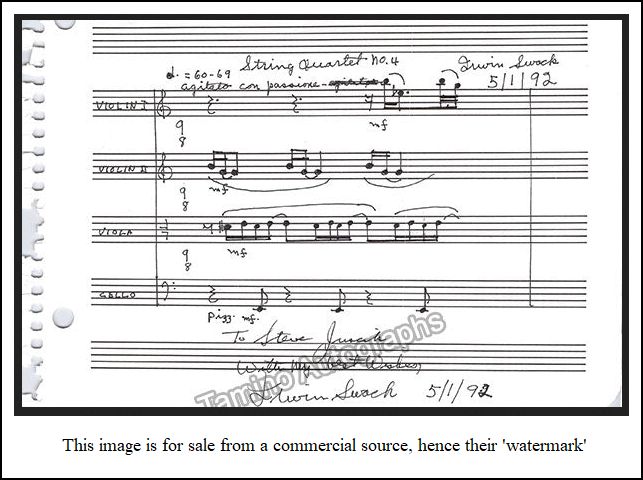

Irwin Swack (November 8, 1916 – January 2, 2006) was an American

composer of contemporary classical music from West Salem, Ohio.

Irwin Swack (November 8, 1916 – January 2, 2006) was an American

composer of contemporary classical music from West Salem, Ohio.

He held degrees from the Cleveland Institute of Music, where he studied violin, graduating with

a B.M. in 1939, the

Juilliard School, Northwestern University (master's degree), and Columbia University (doctorate). He studied with Henry Cowell and Paul

Creston at Columbia University, Gunther Schuller at Tanglewood,

Vittorio Giannini at Juilliard, and Normand Lockwood.

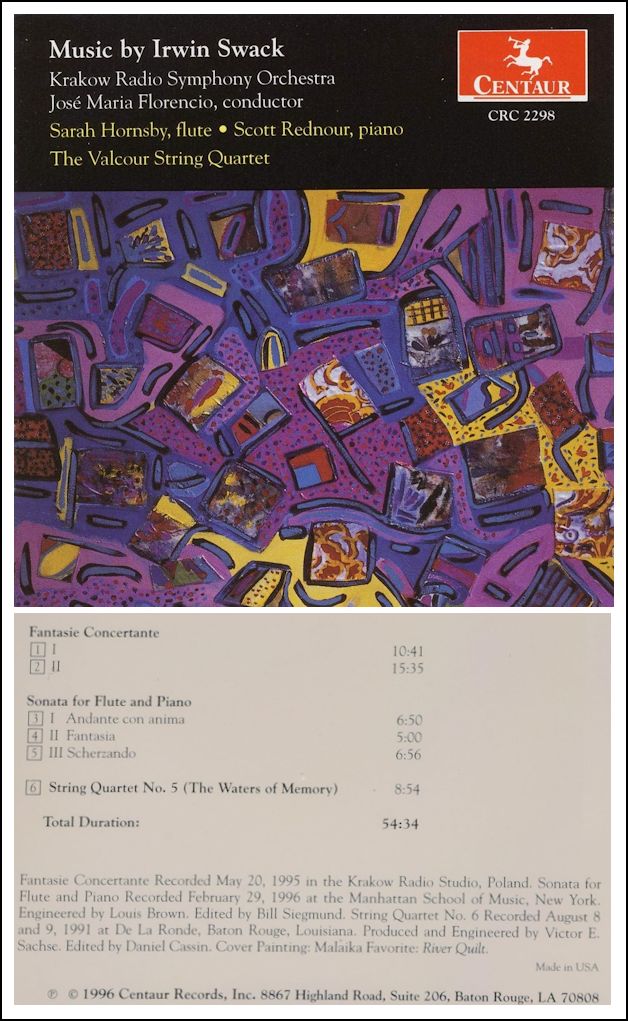

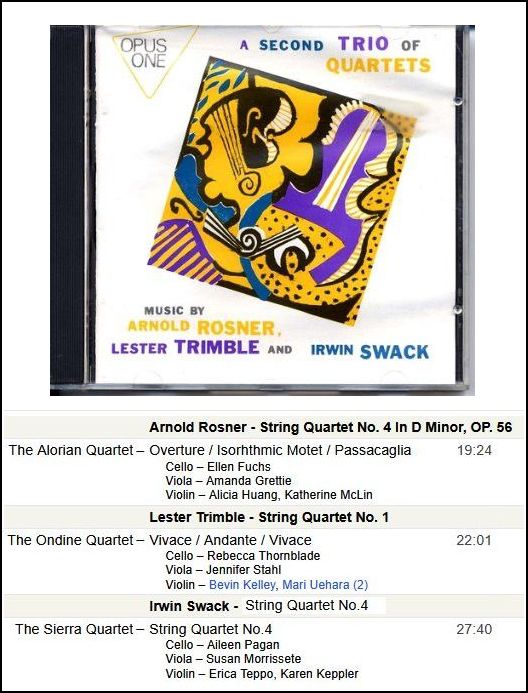

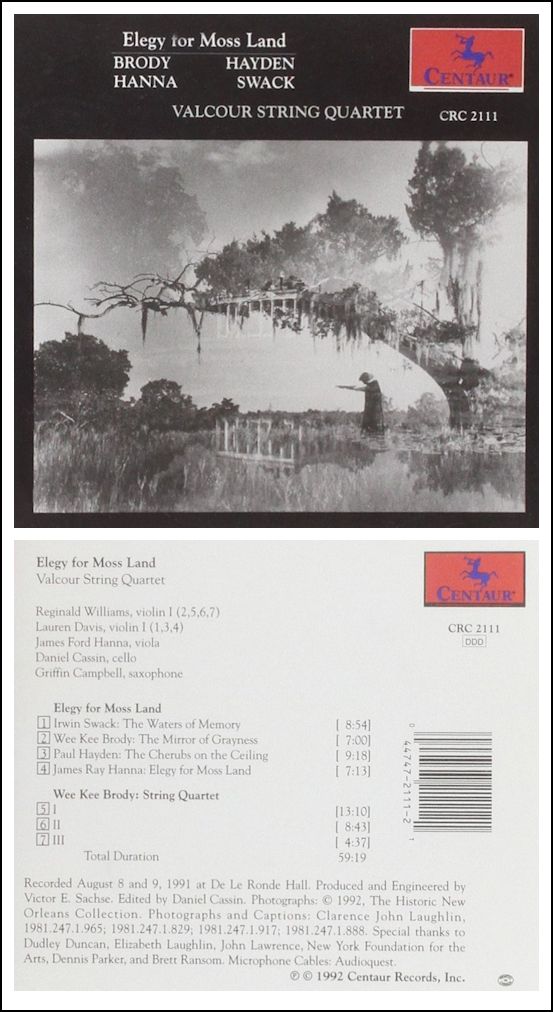

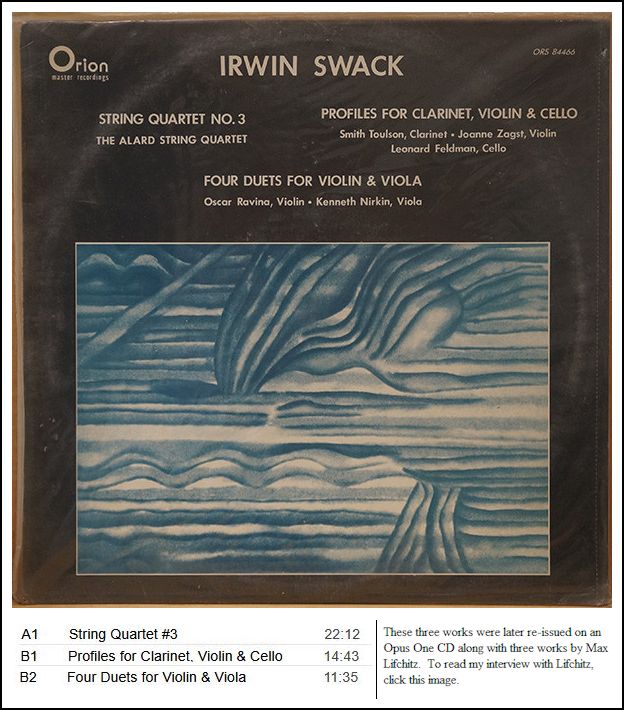

Swack worked as an assistant professor of music at Jacksonville State College. His music was recorded on the Centaur, CRS, Opus One, and Living Artist Recordings labels.

His music is published by Carl Fischer, Shawnee Press, Theodore Presser, and Galaxy Music.