BD: Now I get to meet the other half of the family!

BD: Now I get to meet the other half of the family! BD: Are you pleased with the ones that you’ve made?

BD: Are you pleased with the ones that you’ve made? BD: What advice do you have for the younger singers coming

along today?

BD: What advice do you have for the younger singers coming

along today? BD: Did Meyerbeer write it wrong to make it so difficult?

BD: Did Meyerbeer write it wrong to make it so difficult?|

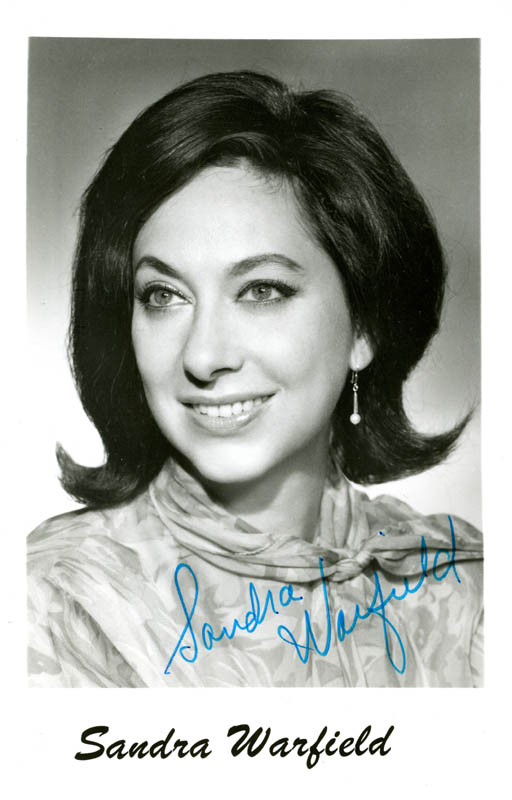

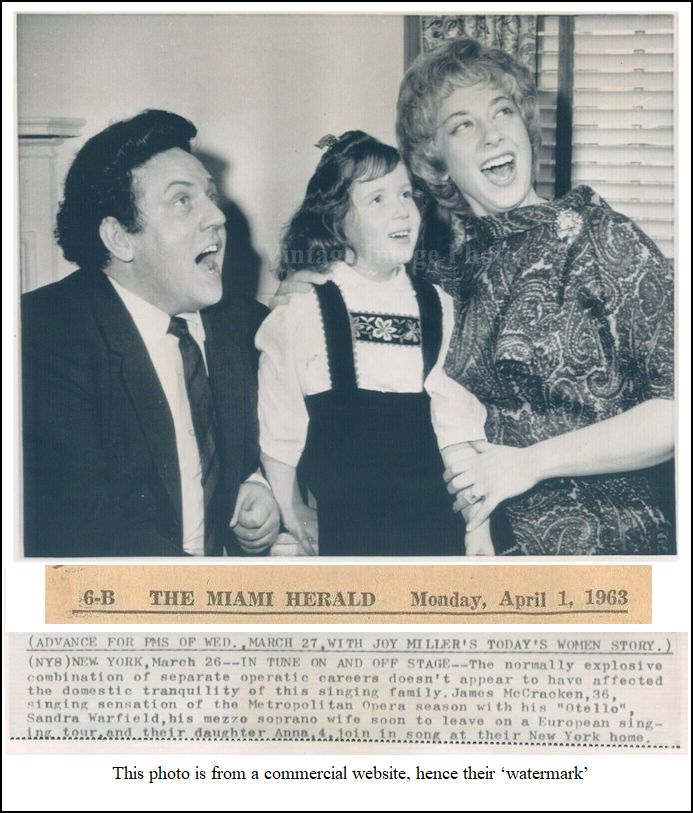

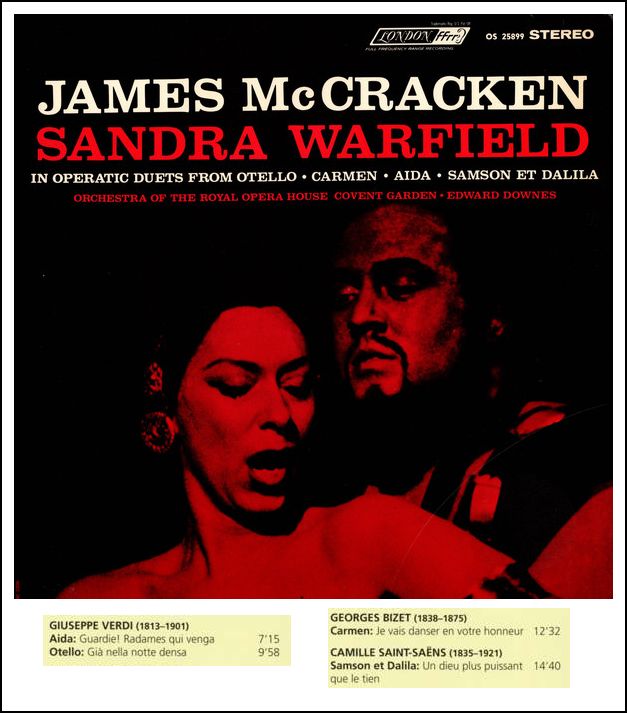

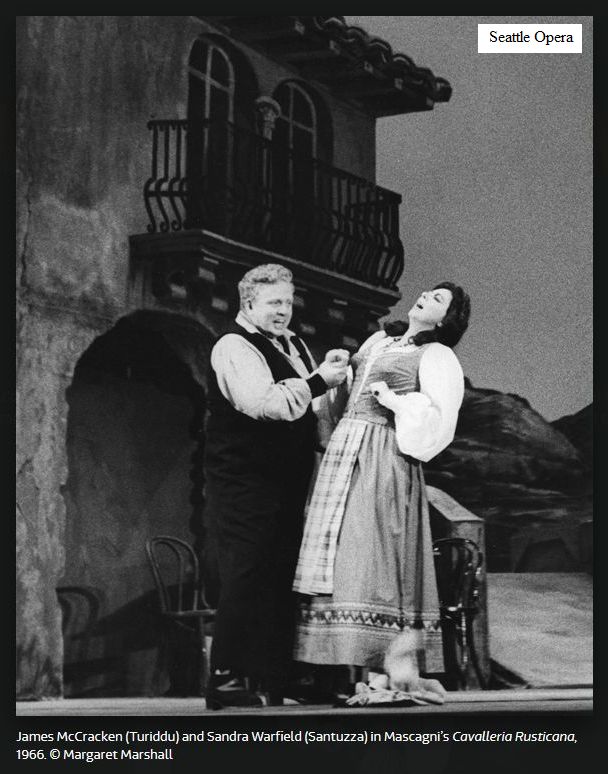

Sandra Warfield (June 8, 1921 – June 29, 2009) was an American operatic mezzo-soprano who performed with New York City's Metropolitan Opera from the 1950s through the 1970s. She was born in Kansas City, Missouri on June 8, 1921, as Flora Jean Bornstein and studied music there at the Kansas City Conservatory of Music (which later became a division of the University of Missouri–Kansas City). She made her stage debut with the Los Angeles Civic Light Opera during the 1940s. In 1950 she portrayed Prince Orlofsky in Die Fledermaus at the Chautauqua Opera. Warfield first appeared on the stage of Metropolitan Opera in a 1953 performance of The Marriage of Figaro, by Mozart, in which she sang the role of a peasant girl. She sang the role of Delilah in Camille Saint-Saëns's Samson and Delilah at a concert in Norfolk, Virginia in 1953 for which she was separately booked with tenor James McCracken, also a fellow performer at the Met, and the two were married shortly thereafter. McCracken left the Met in 1957, complaining that he was not being given lead roles. They moved to Europe, where they spent several years. There she performed with the Zurich Opera, where in 1961 she sang Katerina in the world premiere of Martinů's The Greek Passion. They returned to the United States, and the Metropolitan Opera, in the 1960s. Her performances at the Met included Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi's Un ballo in maschera, Berta in The Barber of Seville by Gioachino Rossini, Marcellina in The Marriage of Figaro, Maddalena in Rigoletto by Verdi and Erda in Richard Wagner's Siegfried, totaling 172 performances. She sang the role of Delilah in Samson and Delilah, with Richard Tucker performing as Samson. In her farewell performance in January 1972, Warfield performed Delilah with her husband as Samson. Following her opera retirement, Warfield began cabaret singing, at such venues as Manhattan's Don't tell mama. Warfield told The New York Times how she was greatly satisfied with cabaret, which allowed her to "express not only the sadness, gladness and hate in opera, but the smallest emotions".Her first marriage to Frank Warfel, which ended in a divorce, became the source of the last name she adopted as a performer. Her second marriage, to James McCracken, ended with his death in April 1988. Warfield and McCracken co-wrote the 1971 memoir A Star in the Family, edited by Robert Daley and published by Coward, McCann & Geoghegan. A resident of Manhattan's Upper East Side, Warfield died at age 88 on June 29, 2009, at Lenox Hill Hospital, due to complications of a stroke. She was survived by a daughter, a stepson, and a grandson. |

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in New York City on March 23, 1988, immediately following my conversation with James McCracken. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.