A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

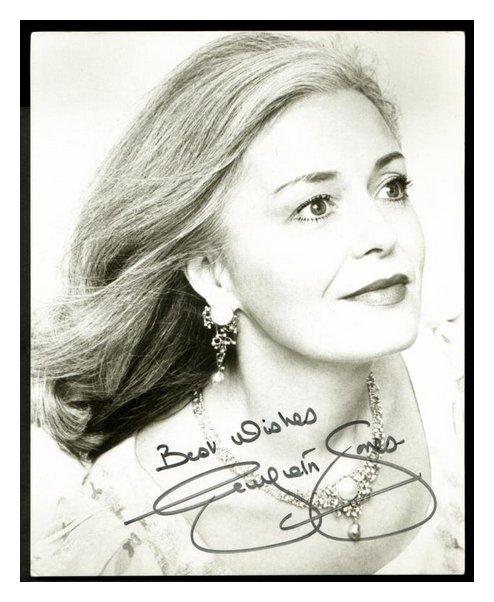

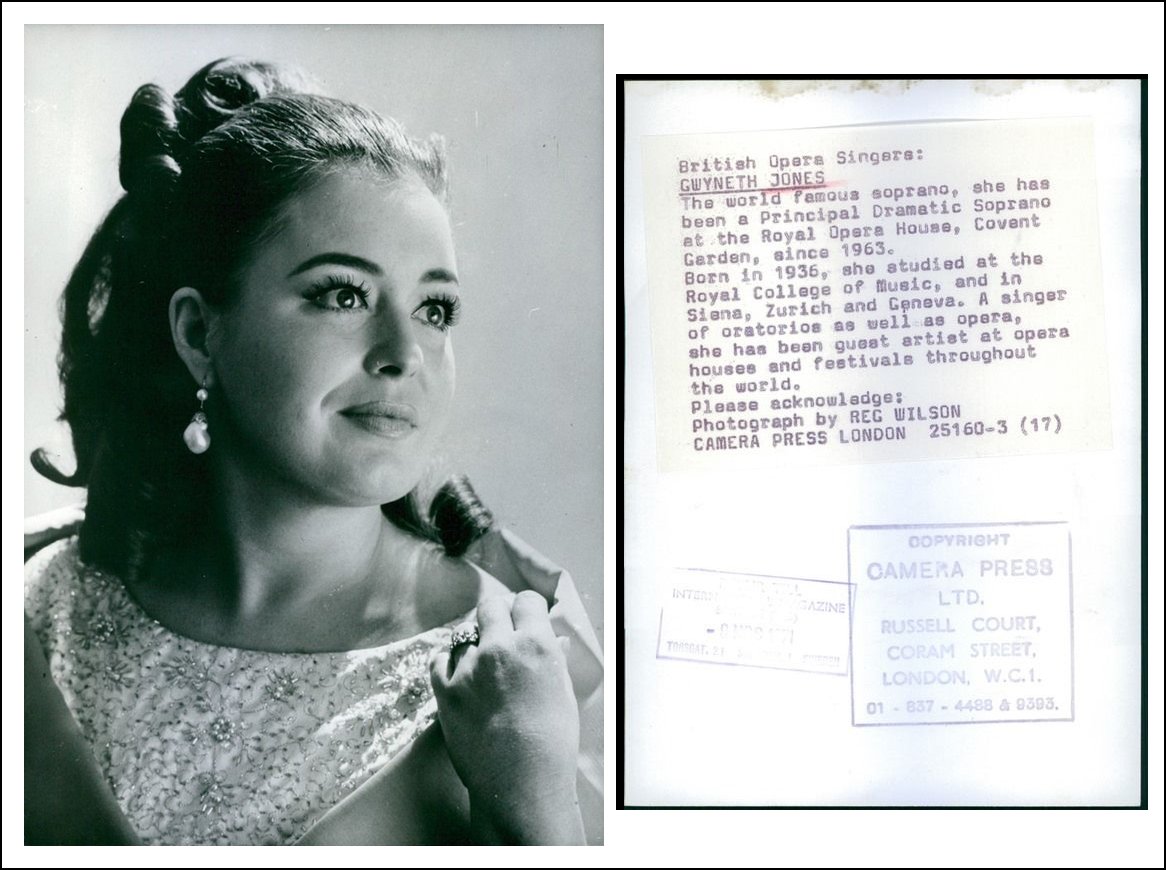

| Gwyneth Jones was born to Edward

George and Violet Webster Jones in 1936, in Pontnewynydd, Wales. Her studies

with Arnold Smith and Ruth Packer at the Royal College of Music in London

were made possible by a scholarship from the County Council. She also studied

at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena, at Herbert Graf's International

Opera Centre in Zurich, and with Maria Carpi in Geneva. Jones' professional

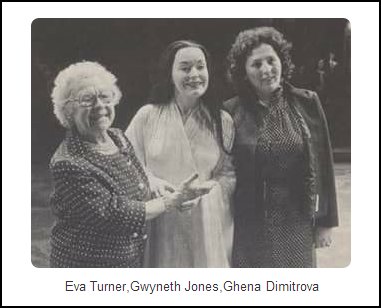

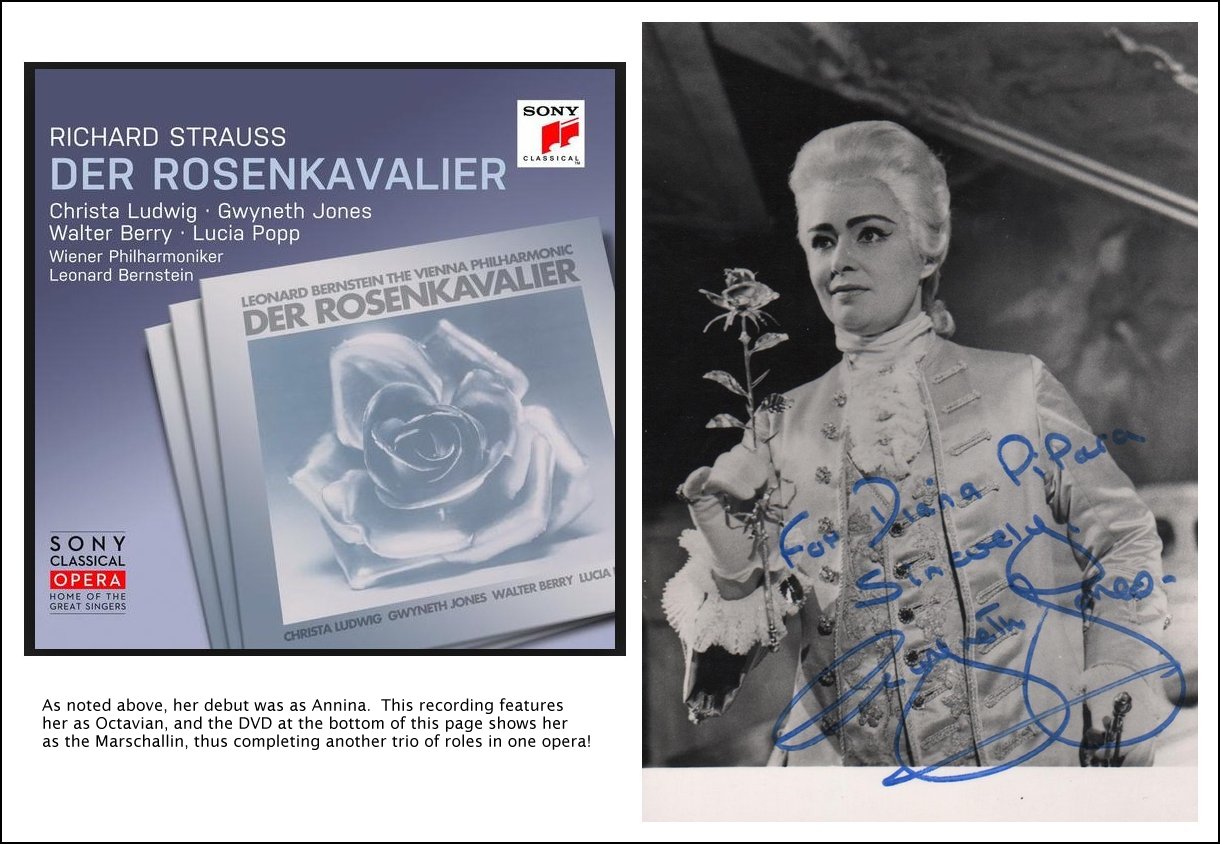

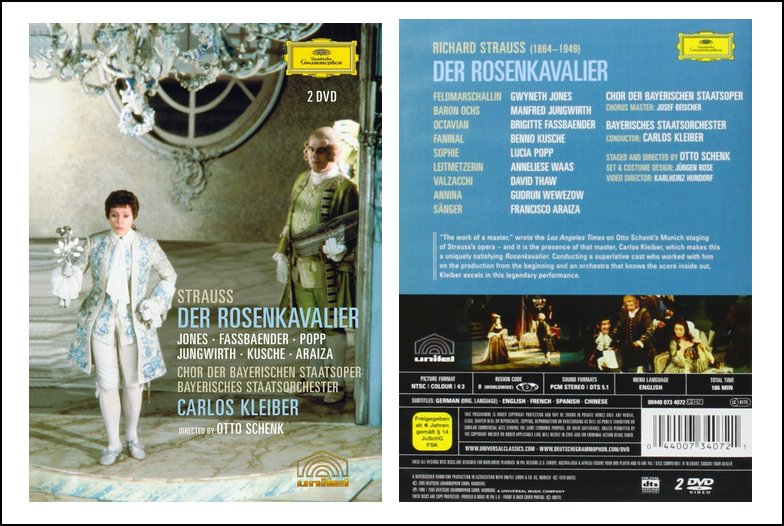

debut, as a mezzo-soprano, was the role of Annina in Der Rosenkavalier with the Zurich Opera

in 1962. Shortly afterwards, she noticed her voice moving upward, which allowed

her to sing her first soprano role of Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera. She was also heard

singing Lady Macbeth for the Welsh National Opera and the Royal Opera, and

heard filling in for Leontyne Price and Régine Crespin

at Covent Garden. [The broadcast of Il

trovatore has been issued by the Royal

Opera, and is shown below.] After

performing roles such as Santuzza, Desdemona, Donna Anna, Aïda, and Tosca,

she made appearances at the Vienna State Opera, La Scala, and at principal

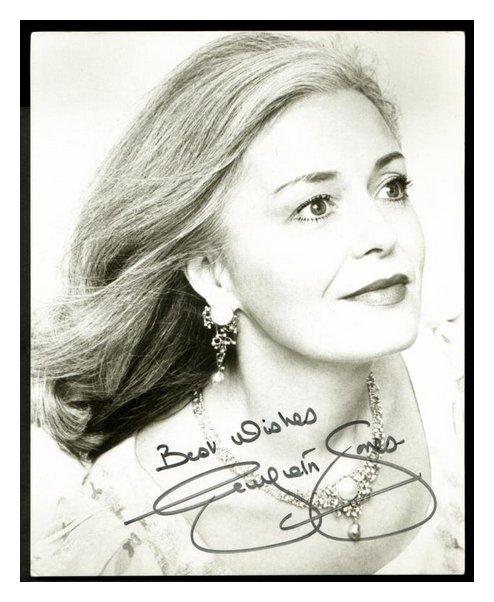

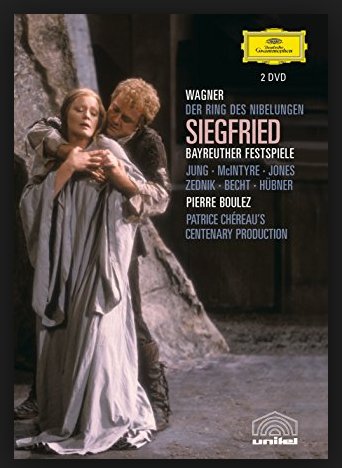

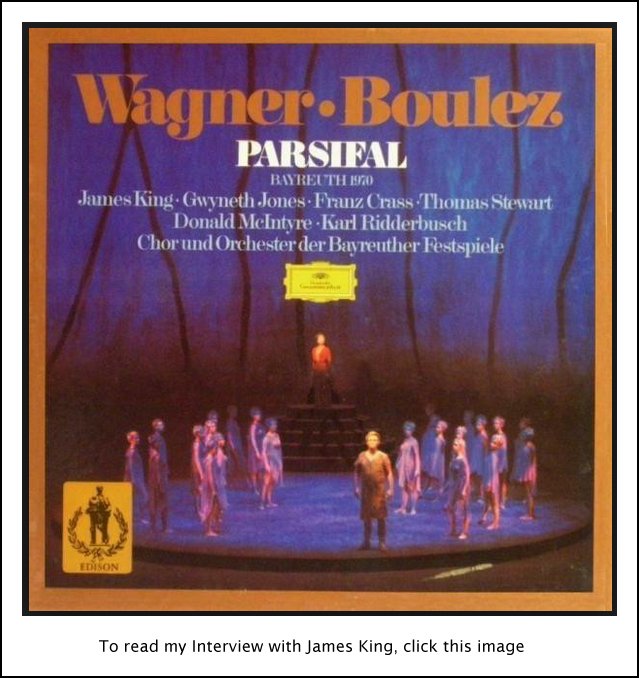

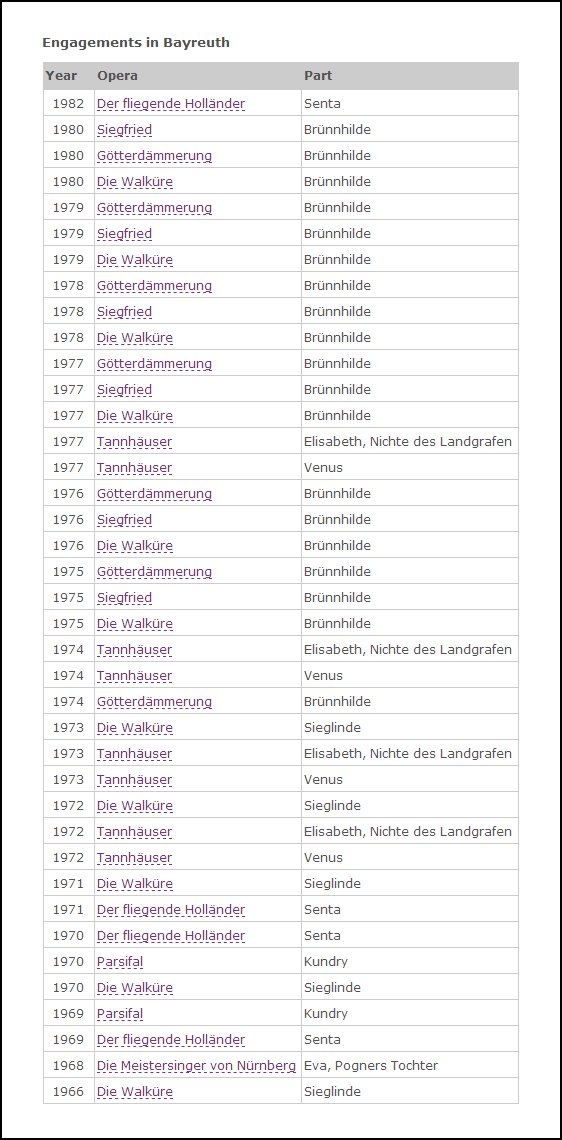

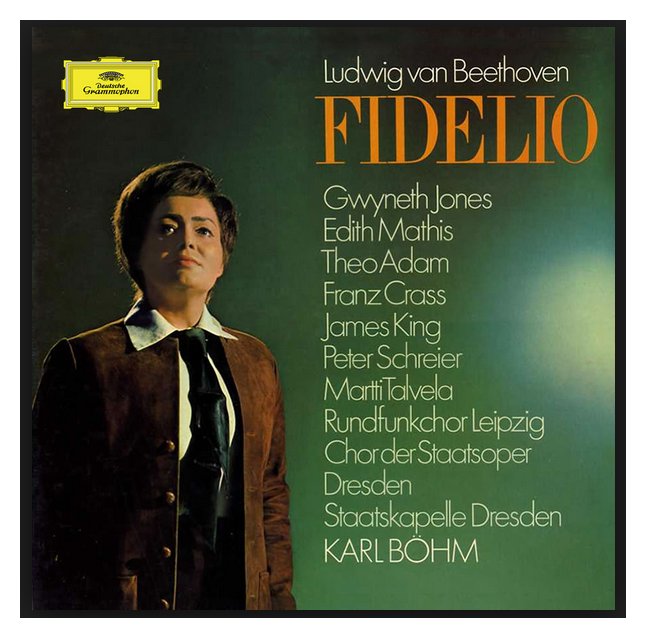

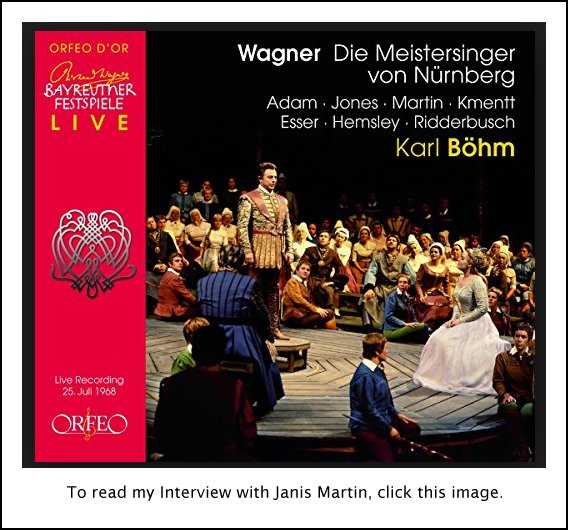

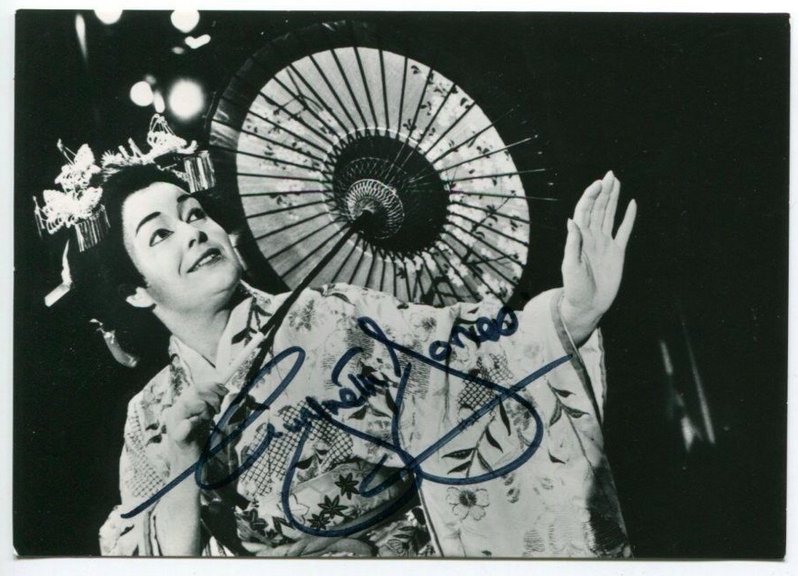

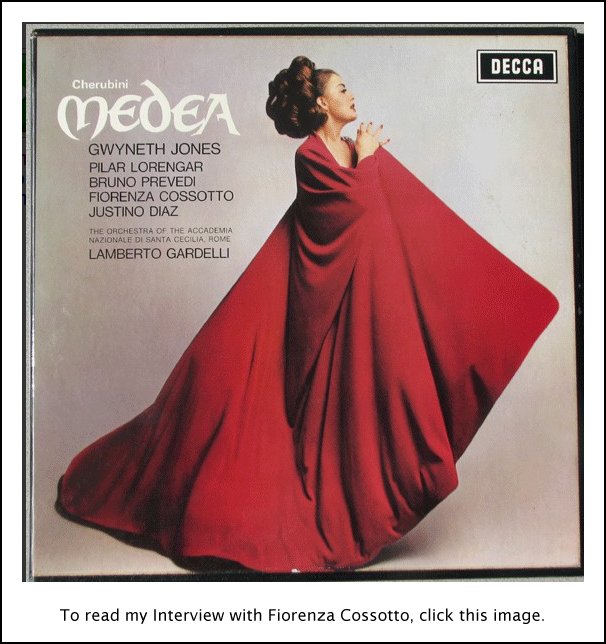

opera houses in Berlin, Paris, Hamburg, and Rome. Shortly after Jones made her 1966 American debut in the title role in Cherubini's Medea, she married Till Haberfeld, a director, with whom she had one child. She achieved American success with her performance of Fidelio with the San Francisco Opera and for her Metropolitan Opera debut as Sieglinde in Die Walküre. One of Jones' greatest achievements was doing all three Brünnhilde roles in the Bayreuth centennial Ring Cycle under Pierre Boulez and Patrice Chéreau. (This Grammy-winning recording is available in both audio and video versions.)  Jones entered a new phase of her career when at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics,

she gave her first performance of Turandot, a role she had learned from her

former teacher Dame Eva

Turner. [Vis-à-vis the photo at left, see my interview with

Ghena Dimitrova.]

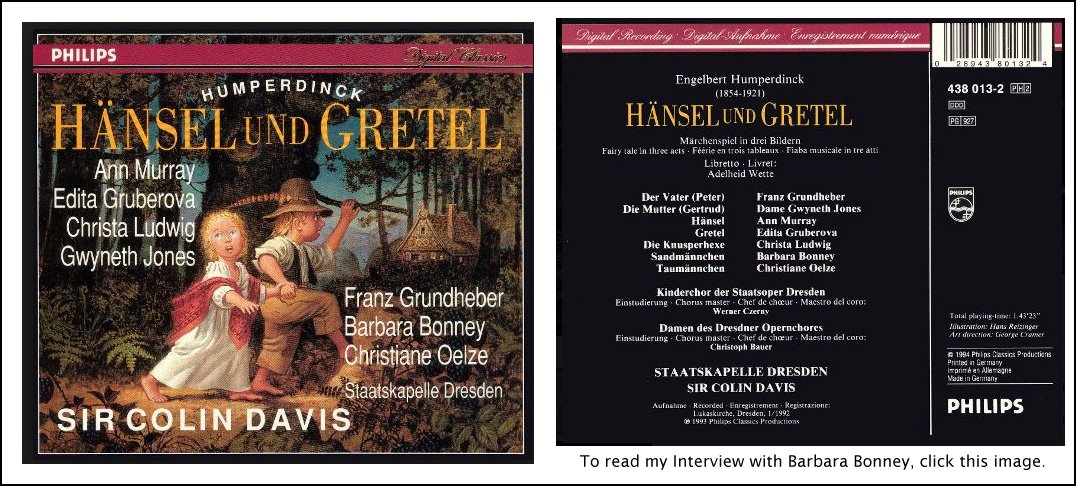

She also took on the roles of Minnie in La Fanciulla del West, the widow Begbick

in Mahagonny, and the mother in

Hänsel und Gretel. She

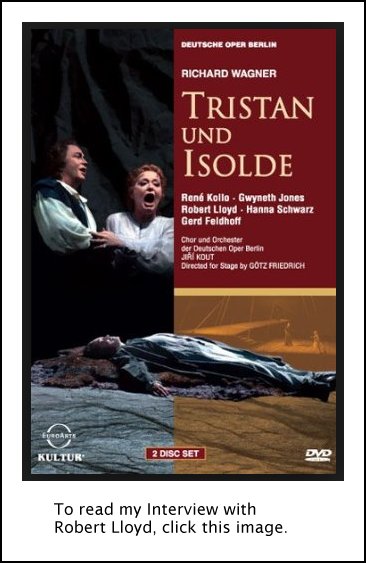

also undertook the roles of both Elisabeth and Venus in Götz Friedrich's

production of Tannhäuser at

the Bayreuth Festival in the 1970’s, and has also been credited with the unique

achievement of having performed all three major female roles in Elektra on stage.

Jones entered a new phase of her career when at the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics,

she gave her first performance of Turandot, a role she had learned from her

former teacher Dame Eva

Turner. [Vis-à-vis the photo at left, see my interview with

Ghena Dimitrova.]

She also took on the roles of Minnie in La Fanciulla del West, the widow Begbick

in Mahagonny, and the mother in

Hänsel und Gretel. She

also undertook the roles of both Elisabeth and Venus in Götz Friedrich's

production of Tannhäuser at

the Bayreuth Festival in the 1970’s, and has also been credited with the unique

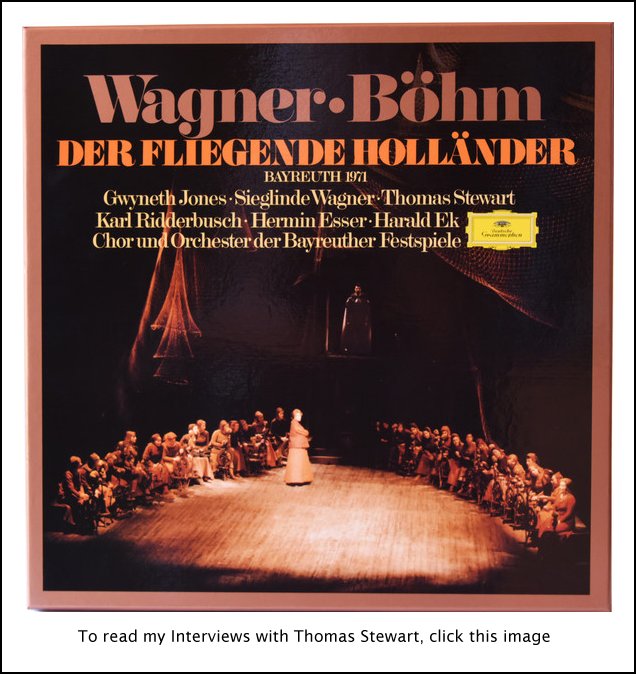

achievement of having performed all three major female roles in Elektra on stage.Jones also performed in concerts and Lieder recitals, television and radio broadcasts and participated in several film projects, including the epic television series, Wagner, in which she played the first Isolde, Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld. She has also devised for herself a couple of one-woman music-theatrical shows - O, Malvina! and Die Frau im Schatten - which are inspired by real historical characters, namely, Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld and Pauline de Ahna (wife of Richard Strauss). The soprano part in the Symphony No. 9, titled "Vision of Eternity", by Welsh composer Alun Hoddinott was written for, and premiered by, her. In 2003 Gwyneth Jones made her debut as director and costume designer in a stage production of Der Fliegende Holländer in Weimar, Germany. She has also given master-classes for young singers and acted as an adjudicator in international vocal competitions, including the 2009 BBC Cardiff Singer of the World competition. In June 2007, she created the role of the Queen of Hearts in the world premiere of Unsuk Chin's new opera, Alice in Wonderland, at the Bavarian State Opera. In February 2008 she sang the part of Herodias in Stephen Langridge's production of Richard Strauss' Salome at Malmö Opera in Sweden. She repeated this role in August 2010, alongside the Salome of Deborah Voigt, in a concert performance at the Verbier Festival in Verbier, Switzerland. Gwyneth Jones was awarded the CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire) in 1976 and was promoted to Dame of the British Empire (DBE) in 1986. She is also the recipient of numerous musical/cultural awards and honours from many different countries and organisations, including the Verdienstkreuz 1. Klasse of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Golden Medal of Honour in Vienna, the Austrian Cross of Honour First Class, the Shakespeare Prize, and the Puccini Award. She is a Kammersängerin at both the Wiener Staatsoper and the Bavarian State Opera as well as awarded Commandeur de L'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in France. She has also been conferred honorary doctorates by the University of Wales and the University of Glamorgan. She is currently the President of the Wagner Society of Great Britain. -- Throughout this page,

names which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website.

BD

|

GJ:

She’s very definitely first a God, and then she becomes human. I first

did it in the Chéreau Ring.

The fact is that Wotan banishes her onto this rock and he takes away in

a way her Godhood. He leaves her there to be found by the first man

that comes along. Actually, the first sort of human feelings that she

has is when she witnesses the love between Sieglinde and Siegmund in the

Valkyrie. This is the first

time she has seen human love expressed, and she’s very deeply moved by this.

This is what makes her then disobey her father, although, as she says, she’s

only doing what she knows is his wish.

GJ:

She’s very definitely first a God, and then she becomes human. I first

did it in the Chéreau Ring.

The fact is that Wotan banishes her onto this rock and he takes away in

a way her Godhood. He leaves her there to be found by the first man

that comes along. Actually, the first sort of human feelings that she

has is when she witnesses the love between Sieglinde and Siegmund in the

Valkyrie. This is the first

time she has seen human love expressed, and she’s very deeply moved by this.

This is what makes her then disobey her father, although, as she says, she’s

only doing what she knows is his wish. GJ:

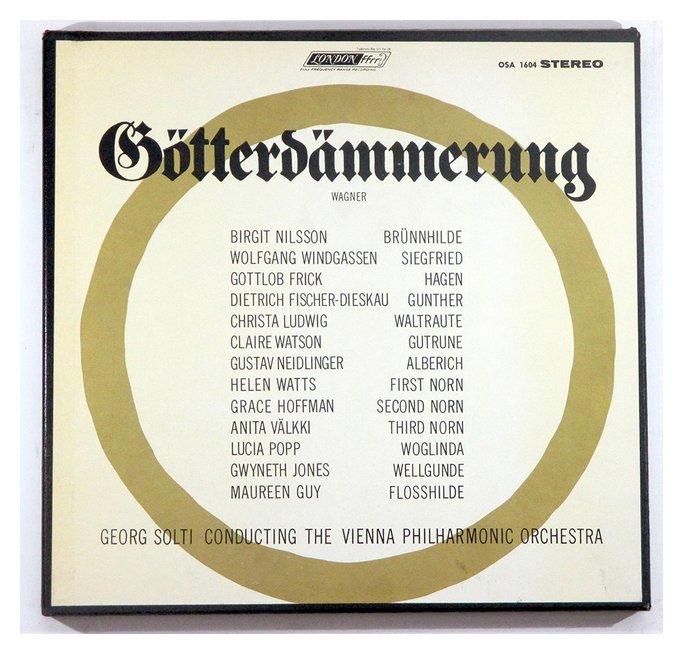

That is very often left over. The thing is that the world goes on, but

this has left the question. If there has been a war, or if there has

been a dictator, or if there’s been somebody bad, it comes to an end and the

world goes on. One doesn’t know if lurking in the background somewhere

there’s another Hagen, or Alberich, or a Hitler, or whoever. One always

hopes for peace, and one always hopes that people can live side by side.

Unfortunately there’s often something that comes along that doesn’t make this

possible.

GJ:

That is very often left over. The thing is that the world goes on, but

this has left the question. If there has been a war, or if there has

been a dictator, or if there’s been somebody bad, it comes to an end and the

world goes on. One doesn’t know if lurking in the background somewhere

there’s another Hagen, or Alberich, or a Hitler, or whoever. One always

hopes for peace, and one always hopes that people can live side by side.

Unfortunately there’s often something that comes along that doesn’t make this

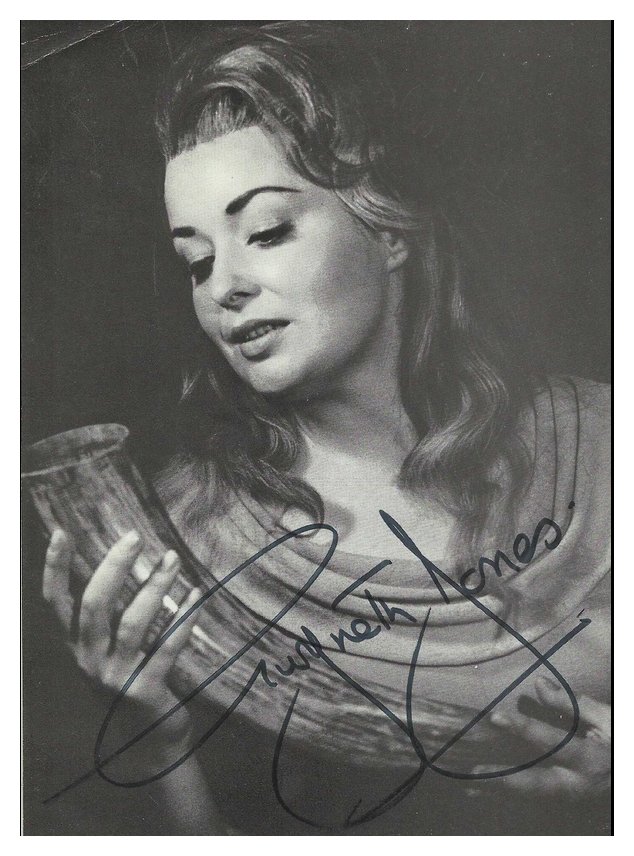

possible. GJ: I don’t think so. They are very long,

and one feels as if you’ve really done a day’s work, so to speak. It’s

really quite a feat to have the energy to support these roles, but this is

something that one is able to do after a lot of experience in the theater.

For instance, I didn’t go near these very heavy long dramatic roles until

I’d had ten years’ experience singing the other roles on stage. Sieglinde

[shown at right] was a great favorite

of mine, and in fact I still sing it occasionally.

GJ: I don’t think so. They are very long,

and one feels as if you’ve really done a day’s work, so to speak. It’s

really quite a feat to have the energy to support these roles, but this is

something that one is able to do after a lot of experience in the theater.

For instance, I didn’t go near these very heavy long dramatic roles until

I’d had ten years’ experience singing the other roles on stage. Sieglinde

[shown at right] was a great favorite

of mine, and in fact I still sing it occasionally. BD:

Oh, so she’s too late?

BD:

Oh, so she’s too late? GJ: Oh, absolutely. He knew what he was doing

when he built the theater. It’s not a large theater, but everything

is made of wood, so the sound is very beautiful and mellow. And the

orchestra pit is especially designed for the instruments of Wagner’s orchestra.

He knew, with all this brass, they are placed right under the stage with the

sound projecting up to what they call the Deckel. It is a curved lid into

which the sound from the stage and the orchestra bounds and rebounds and comes

out mixed together into the audience. It’s something very unique, and

it certainly enables one to hear very well the sound of the orchestra and

voices ideally mixed. Also, because the orchestra is covered, the audience

are not disturbed by the lights of the orchestra, and seeing musicians playing.

They are concentrating only on the picture, the acting that is happening

on stage. What Wagner wanted was not to have one’s concentration in

any way disturbed in this room. There’s one focal point. In a

performance of opera, the arms of the conductor and various lights can be

distracting.

GJ: Oh, absolutely. He knew what he was doing

when he built the theater. It’s not a large theater, but everything

is made of wood, so the sound is very beautiful and mellow. And the

orchestra pit is especially designed for the instruments of Wagner’s orchestra.

He knew, with all this brass, they are placed right under the stage with the

sound projecting up to what they call the Deckel. It is a curved lid into

which the sound from the stage and the orchestra bounds and rebounds and comes

out mixed together into the audience. It’s something very unique, and

it certainly enables one to hear very well the sound of the orchestra and

voices ideally mixed. Also, because the orchestra is covered, the audience

are not disturbed by the lights of the orchestra, and seeing musicians playing.

They are concentrating only on the picture, the acting that is happening

on stage. What Wagner wanted was not to have one’s concentration in

any way disturbed in this room. There’s one focal point. In a

performance of opera, the arms of the conductor and various lights can be

distracting.  GJ:

Ah, Fidelio! What would you like to know? She is one of the

most wonderful women. Fidelio

is very much a piece that could be played in our time, with the political

prisoners, and the wife who is disguising herself and sacrificing herself

because of her great love for her husband.

GJ:

Ah, Fidelio! What would you like to know? She is one of the

most wonderful women. Fidelio

is very much a piece that could be played in our time, with the political

prisoners, and the wife who is disguising herself and sacrificing herself

because of her great love for her husband.  BD:

So it’s more than just an escape?

BD:

So it’s more than just an escape?

BD: I take it you don’t subscribe to that theory?

BD: I take it you don’t subscribe to that theory?

© 1985 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on June 15, 1985. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.