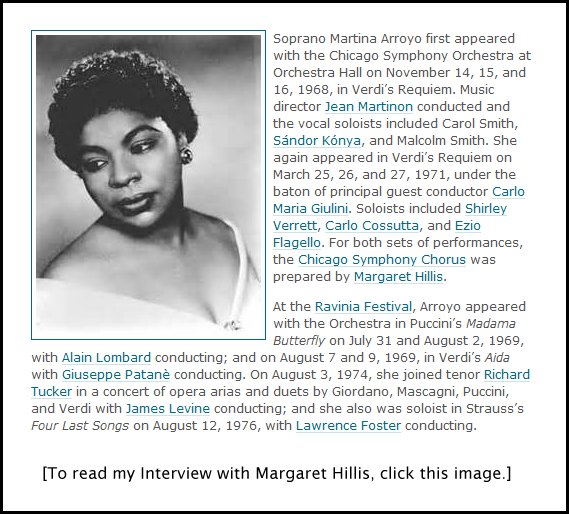

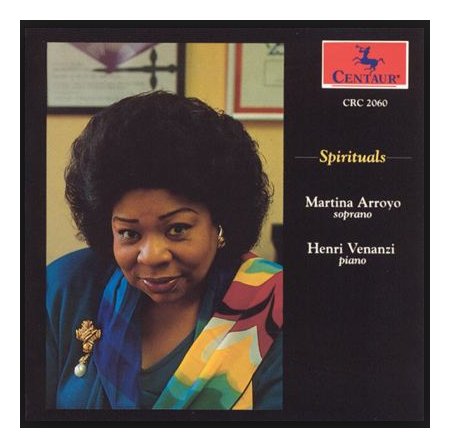

American soprano Martina Arroyo has

received numerous awards and accolades for her long-standing pre-eminence

at the world’s foremost opera houses and concert halls, including a 2013

Kennedy Center Honors and a 2010 Opera Honors Award from the National Endowment

for the Arts. She continues to make an invaluable contribution to the art

form through her teaching and her commitment to young artist development

through the Martina Arroyo Foundation.

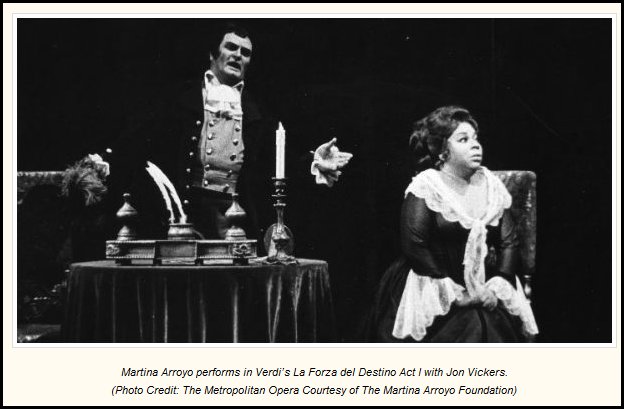

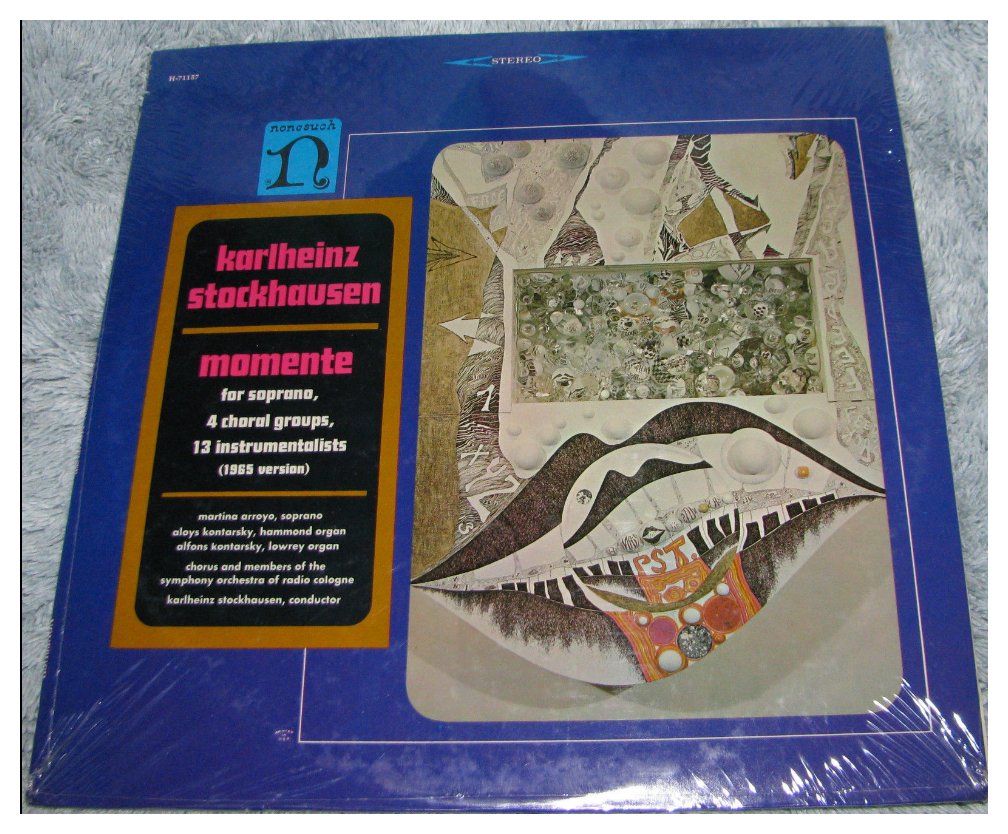

Born in 1937 and raised in Harlem, Arroyo went on to conquer the opera world, from the Metropolitan Opera to the Vienna State Opera, Teatro Colón in Buenos Aires to La Scala in Milan, Paris Opera to the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden, and the great concert halls from Salzburg and Berlin to her hometown of New York. She has had the honor of three opening night performances at the Met, two of them in consecutive seasons. Few in her generation have been so fearless or so successful across the repertory, from Mozart, Verdi, Puccini and Strauss to Barber, Bolcom, Schoenberg, and Stockhausen. The New York Times once heralded her voice as “among the most glorious in the world.” Her extensive recorded legacy reflects her inspired collaborations with conductors Leonard Bernstein, Karl Böhm, Rafael Kubelík, Zubin Mehta, Thomas Schippers, Colin Davis, and James Levine. Arroyo studied to be a teacher, and graduated from Hunter College at the age of 19. In 1958, she auditioned for and won the Metropolitan Opera’s Auditions of the Air, which gave her a chance to study both music and acting at the Met’s Kathryn Long School. She made her Carnegie Hall debut in 1958 in the American premiere of Ildebrando Pizzetti’s Murder in the Cathedral, and in 1965 stepped in as a last-minute replacement for an ailing Birgit Nilsson in Aïda at the Met, a career-changing moment. Over the years and in nearly 200 performances at the Met, Arroyo performed all the major Verdi roles that would be the core of her repertory, in addition to Mozart’s Donna Anna, Puccini’s Cio-Cio-San and Liù, Mascagni’s Santuzza, Ponchielli’s Gioconda, and Wagner’s Elsa. Her 1968 London debut came in a concert version of Meyerbeer’s epic Les Huguenots, followed the same year by her Covent Garden debut in Aïda. Her debuts at Paris Opera, La Scala and the Teatro Colón followed in close succession. In 2003, Arroyo established her own non-profit cultural organization which provides new generations of emerging young artists with the tools to pursue careers in opera, by means of two intensive programs of study, coaching, and performance that focus on immersive preparation of complete operatic roles. -- From the official site of

Martina Arroyo.

--Note: Names which are links in this box and in the interview below refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

Arroyo sang quite a number of times in Chicago at various venues.

She was heard at Orchestra Hall as well as the Ravinia Festival with the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and at Grant Park, the Auditorium and at a few

smaller locations. With Lyric Opera she sang Un Ballo in Maschera in 1972 with Franco

Tagliavini, Sherrill Milnes,

Ruza Baldani, Urszula

Koszut, conducted by Christoph

von Dohnányi and directed by Tito Gobbi; and she opened

the 1974 season in Simon Boccanegra

with Piero Cappuccilli,

Carlo Cossutta, Ruggero

Raimondi, conducted by Bruno Bartoletti.

Arroyo sang quite a number of times in Chicago at various venues.

She was heard at Orchestra Hall as well as the Ravinia Festival with the

Chicago Symphony Orchestra, and at Grant Park, the Auditorium and at a few

smaller locations. With Lyric Opera she sang Un Ballo in Maschera in 1972 with Franco

Tagliavini, Sherrill Milnes,

Ruza Baldani, Urszula

Koszut, conducted by Christoph

von Dohnányi and directed by Tito Gobbi; and she opened

the 1974 season in Simon Boccanegra

with Piero Cappuccilli,

Carlo Cossutta, Ruggero

Raimondi, conducted by Bruno Bartoletti.

MA: Ah, yes, but I’m not going to tell you which!

[Both laugh] There are a few who are close in some respects.

I’ve never been in a situation, for example, like Amelia [in Ballo in Maschera] with the conflict

with her husband and the King (or the governor, depending on the production),

but it is the vulnerability of this problem, the situation that I can relate

to immediately. I love Amelia. I don’t think you should sing

a character unless you do love her, or him, because you do it with truth.

If you don’t love that person, or at least if you can’t identify closely

to it because of a real truth for you, the audience knows. I don’t

think you can say you’re going to behave this way or be this character and

comment about it at the same time. You’re in the role or you’re

not in the role, and if you’re in the role then you’ve got to do her honestly.

And if you don’t believe it, if you don’t care about her, if you don’t care

closely with real heart, it shows. You know the people on stage that

are just indicating their character, and those who are trying to live it.

MA: Ah, yes, but I’m not going to tell you which!

[Both laugh] There are a few who are close in some respects.

I’ve never been in a situation, for example, like Amelia [in Ballo in Maschera] with the conflict

with her husband and the King (or the governor, depending on the production),

but it is the vulnerability of this problem, the situation that I can relate

to immediately. I love Amelia. I don’t think you should sing

a character unless you do love her, or him, because you do it with truth.

If you don’t love that person, or at least if you can’t identify closely

to it because of a real truth for you, the audience knows. I don’t

think you can say you’re going to behave this way or be this character and

comment about it at the same time. You’re in the role or you’re

not in the role, and if you’re in the role then you’ve got to do her honestly.

And if you don’t believe it, if you don’t care about her, if you don’t care

closely with real heart, it shows. You know the people on stage that

are just indicating their character, and those who are trying to live it. BD: So everything affects your voice?

BD: So everything affects your voice? MA: Well, you’ve never really left her altogether!

I can’t tell you what it is like for my colleagues, but for me it depends

on the type of role. A role like Butterfly or Tosca takes much more

time for me to come down because you get so wound up in these characters.

Donna Anna takes less time, for even though you’re involved, somehow the

verismo roles touch that nerve of the body that makes the whole body need

more time. That’s all I can say. Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera takes more time

for me to let go than Aïda. That’s just personal.

MA: Well, you’ve never really left her altogether!

I can’t tell you what it is like for my colleagues, but for me it depends

on the type of role. A role like Butterfly or Tosca takes much more

time for me to come down because you get so wound up in these characters.

Donna Anna takes less time, for even though you’re involved, somehow the

verismo roles touch that nerve of the body that makes the whole body need

more time. That’s all I can say. Amelia in Un Ballo in Maschera takes more time

for me to let go than Aïda. That’s just personal.  MA: It helps if you’re working onto your maximum,

as much as you can. But even your maximum is not always the same.

If everything is working for you and is going well, everything is going on

with the others. Sometimes you react very much to your colleagues,

or something is not going along with your colleagues. You can react

with each other’s nerves. You give all the time — or

at least I certainly do — but you don’t give on the

basis of whether or not they’re applauding a great deal. You give on

the basis of what you have to say and how it’s being said. Is the person

reacting to you? It’s a give and take, but if it’s happening, the audience

is with you. I’ve never been in a performance when something was happening

on stage and the audience didn’t like it. So one way or the other,

I don’t even imagine that situation. I have been in performances when

not a lot was happening on stage and the audience was giving out like crazy.

I am not talking about giving or about applauding, I’m talking about there

being something in the air. There’s something, and you feel you’re

there to enjoy. Therefore there’s reason together to entertain you.

You’re there to be entertained, to enjoy the evening. A few weeks ago

I went to see Mefistofele at the

State Theatre in New York. I had not seen Mefistofele before, and I was excited,

I can tell you. I went in ready for a good performance, and they didn’t

let me down. They were wonderful, the whole cast. It was a good

performance and I left there on cloud nine, and so were my friends and our

crowd. The people on stage must have known that we were happy to be

in the audience. We knew that they had made us happy, and so it’s there.

I wouldn’t want to measure it!

MA: It helps if you’re working onto your maximum,

as much as you can. But even your maximum is not always the same.

If everything is working for you and is going well, everything is going on

with the others. Sometimes you react very much to your colleagues,

or something is not going along with your colleagues. You can react

with each other’s nerves. You give all the time — or

at least I certainly do — but you don’t give on the

basis of whether or not they’re applauding a great deal. You give on

the basis of what you have to say and how it’s being said. Is the person

reacting to you? It’s a give and take, but if it’s happening, the audience

is with you. I’ve never been in a performance when something was happening

on stage and the audience didn’t like it. So one way or the other,

I don’t even imagine that situation. I have been in performances when

not a lot was happening on stage and the audience was giving out like crazy.

I am not talking about giving or about applauding, I’m talking about there

being something in the air. There’s something, and you feel you’re

there to enjoy. Therefore there’s reason together to entertain you.

You’re there to be entertained, to enjoy the evening. A few weeks ago

I went to see Mefistofele at the

State Theatre in New York. I had not seen Mefistofele before, and I was excited,

I can tell you. I went in ready for a good performance, and they didn’t

let me down. They were wonderful, the whole cast. It was a good

performance and I left there on cloud nine, and so were my friends and our

crowd. The people on stage must have known that we were happy to be

in the audience. We knew that they had made us happy, and so it’s there.

I wouldn’t want to measure it!  MA: Psychologically, yes. You say that you’re

not, but having a microphone in front of your nose blows my mind! I

just don’t like the idea. Remember we were talking about knowing the

fourth wall is there? Well, it’s worse when you have something shoved

right in your face. When there are no mikes up in front of the nose,

I’m just singing and relating to people personally. That person might

be there [points close to us] or might be way over there [points far across

the room], but it’s a human being that’s responding.

MA: Psychologically, yes. You say that you’re

not, but having a microphone in front of your nose blows my mind! I

just don’t like the idea. Remember we were talking about knowing the

fourth wall is there? Well, it’s worse when you have something shoved

right in your face. When there are no mikes up in front of the nose,

I’m just singing and relating to people personally. That person might

be there [points close to us] or might be way over there [points far across

the room], but it’s a human being that’s responding. BD: And it will happen!

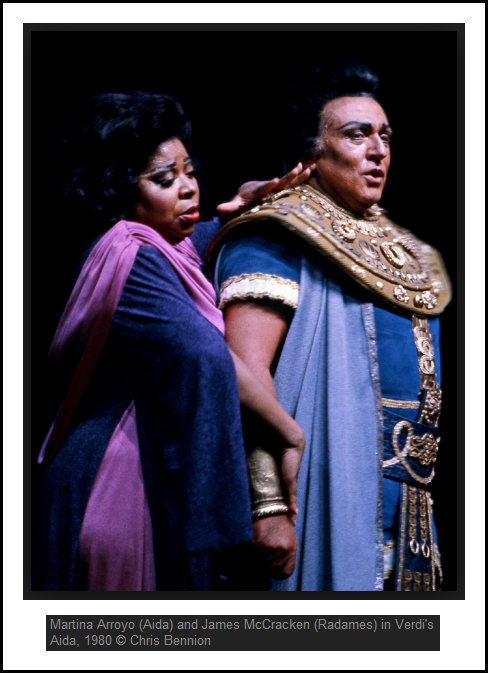

BD: And it will happen! MA: She’s not an easy lady to portray. If

you play her superficially — just whatever happens to

her happens and she lets fate take her where it has to go — it’s

almost easier than if you really try to work with her. This girl loves

her father and loves her home, and it terrible to do something against someone

that you know is going to hurt them. In the end she does sacrifice

her own happiness for him, and he, too. You’re not talking about a

clear good person or a clear bad person. You’re talking about very

wonderful people themselves that are hurting each other. They are causing

pain but not wanting to. They are causing unhappiness they don’t want

to cause. They are forced to commit acts that they ordinarily would

not commit.

MA: She’s not an easy lady to portray. If

you play her superficially — just whatever happens to

her happens and she lets fate take her where it has to go — it’s

almost easier than if you really try to work with her. This girl loves

her father and loves her home, and it terrible to do something against someone

that you know is going to hurt them. In the end she does sacrifice

her own happiness for him, and he, too. You’re not talking about a

clear good person or a clear bad person. You’re talking about very

wonderful people themselves that are hurting each other. They are causing

pain but not wanting to. They are causing unhappiness they don’t want

to cause. They are forced to commit acts that they ordinarily would

not commit.

© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded at her hotel in Chicago on September 26, 1988. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1991 and 1996. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.