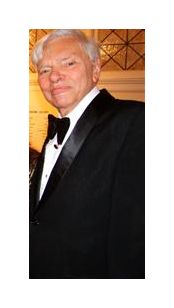

| Dan Tucker (1925–2010) was a composer in

residence for the Music Institute of Chicago, which premiered many of

his works. Tucker was on the Editorial Board for the Chicago Tribune

from 1975 until his retirement in 1988. He was one of the very few classical

composers since Virgil Thomson

to have held a major editorial position with a major metropolitan newspaper

in a major American city. Tucker was born in Chicago, and after service in the U.S. Army from 1943 to 1946, he continued working as a journalist. Meanwhile, he took bachelor’s and master’s degrees in piano and composition from the American Conservatory of Music. He combined two careers as newspaperman and composer from 1953 until 1988, when he retired from the editorial board of the Chicago Tribune to concentrate on music. Over the last four decades, critics have praised his music for its “flair for melody” (Joseph McLellan, Washington Post), and for qualities they have called “moving,” “impish,” “hallucinating,” and even “sublime.” In all the evolving styles and idioms that Tucker’s music has reflected in that time, melody has always been its mainstay, and remains so now that “melody” is no longer a word of critical scorn. |

BD: Do you feel that if it had been a straight commission

you could have wrestled with it and made it work?

BD: Do you feel that if it had been a straight commission

you could have wrestled with it and made it work? BD: Tom Willis [Music

Critic of the Tribune] used to say, “Today’s

newspaper wraps tomorrow’s fish.”

I assume you want your music to last a few more days?

BD: Tom Willis [Music

Critic of the Tribune] used to say, “Today’s

newspaper wraps tomorrow’s fish.”

I assume you want your music to last a few more days? BD: Is the music of Tucker threatening?

BD: Is the music of Tucker threatening? BD: The hours fit what you want?

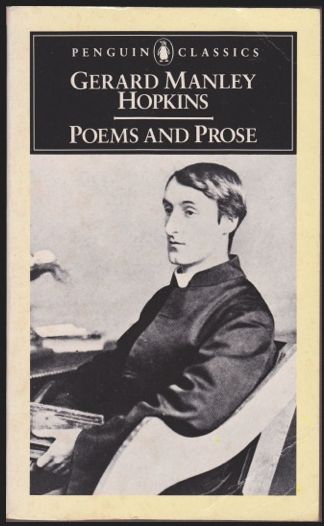

BD: The hours fit what you want? Gerard Manley Hopkins SJ (28 July

1844 – 8 June 1889) was an English poet and Jesuit priest, whose posthumous

fame established him among the leading Victorian poets. His manipulation

of prosody – particularly his concept of sprung rhythm – established him

as an innovative writer of verse, as did his technique of praising God

through vivid use of imagery and nature. Only after his death did Robert

Bridges begin to publish a few of Hopkins's mature poems in anthologies,

hoping to prepare the way for wider acceptance of his style. By 1930 his

work was recognized as one of the most original literary accomplishments

of his century. It had a marked influence on such leading 20th-century

poets as T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil

Day-Lewis.

Gerard Manley Hopkins SJ (28 July

1844 – 8 June 1889) was an English poet and Jesuit priest, whose posthumous

fame established him among the leading Victorian poets. His manipulation

of prosody – particularly his concept of sprung rhythm – established him

as an innovative writer of verse, as did his technique of praising God

through vivid use of imagery and nature. Only after his death did Robert

Bridges begin to publish a few of Hopkins's mature poems in anthologies,

hoping to prepare the way for wider acceptance of his style. By 1930 his

work was recognized as one of the most original literary accomplishments

of his century. It had a marked influence on such leading 20th-century

poets as T. S. Eliot, Dylan Thomas, W. H. Auden, Stephen Spender and Cecil

Day-Lewis. Hopkins studied classics at Balliol College, Oxford (1863–1867). He began his time in Oxford as a keen socialite and prolific poet, but he seems to have alarmed himself with the changes in his behavior that resulted. At Oxford he forged a lifelong friendship with Robert Bridges (eventual Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom), which would be of importance in his development as a poet, and in establishing his posthumous acclaim. Hopkins was deeply impressed with the work of Christina Rossetti, and she became one of his greatest contemporary influences, meeting him in 1864. During this time he studied with the eminent writer and critic Walter Pater, who tutored him in 1866 and remained a friend until Hopkins left Oxford in September 1879. In the late 1880s Hopkins met Father Matthew Russell, the Jesuit founder and editor of the Irish Monthly magazine, who presented him to Katharine Tynan and W. B. Yeats. In 1884 he became professor of Greek and Latin at University College Dublin. His English roots and his disagreement with the Irish politics of the time, as well as his own small stature (5 feet 2 inches), unprepossessing nature and personal oddities meant that he was not a particularly effective teacher. This, as well as his isolation in Ireland, deepened his gloom. His poems of the time, such as "I Wake and Feel the Fell of Dark, not Day", reflected this. They came to be known as the "terrible sonnets", not because of their quality but because according to Hopkins's friend Canon Richard Watson Dixon, they reached the "terrible crystal", meaning that they crystallised the melancholic dejection that plagued the later part of Hopkins's life. Several issues brought about this melancholic state and restricted his poetic inspiration during the last five years of his life. His workload was extremely heavy. He disliked living in Dublin, away from England and friends. He was also disappointed at how far the city had fallen from its Georgian elegance of the previous century. His general health deteriorated as his eyesight began to fail. He felt confined and dejected. As a devout Jesuit, he found himself in an artistic dilemma. To subdue any egotism which would violate the humility required by his religious position, he decided never to publish his poems. But Hopkins realised that any true poet requires an audience for criticism and encouragement. This conflict between his religious obligations and his poetic talent caused him to feel that he had failed them both. After suffering ill health for several years and bouts of diarrhoea, Hopkins died of typhoid fever in 1889 and was buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, following his funeral in Saint Francis Xavier Church on Gardiner Street, located in Georgian Dublin. He is thought to have suffered throughout his life from what today might be diagnosed as either bipolar disorder or chronic unipolar depression, and battled a deep sense of melancholic anguish. However, on his death bed, his last words were, "I am so happy, I am so happy. I loved my life." He was 44 years of age. Christopher Ricks called Hopkins "the most original poet of the Victorian age." Hopkins is considered as influential as T. S. Eliot in initiating the modern movement in poetry. His experiments with elliptical phrasing and double meanings and quirky conversational rhythms turned out to be liberating to poets such as W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas. |

|

Hundreds of flags were waving, and a few who lacked flags found other things to wave. Somebody in the middle of the crowd had a jolly, green, giant Gumby toy, so he waved that. Others simply waved their hands at the television cameras, and a few had their images carried to a nationwide television audience of millions via PBS. It was grand for other things, too. Music conducted by Mstislav

Rostropovich and fireworks by the Santore family, as well as a day perfect

for picnicking on the Capitol grounds and the Mall, attracted a record-breaking

crowd. [Everyone] was in a holiday mood, ready to applaud generously on the slightest provocation and plunging whole-heartedly into traditional holiday activities: children getting lost, couples nibbling picnic lunches and sipping a variety of beverages, occasional individuals listening to portable radios on headphones, balloons escaping and hurrying off in the general direction of Union Station.

The concert, titled "A Capitol Fourth," featured a mixed bag of European

classics conducted by Rostropovich, American popular songs sung by Tony

Bennett, and ceremonial musical tributes to the American dream, sung by

Sherrill Milnes.

Rostropovich also conducted a six-minute world premiere: the "Differences"

Overture from the "American Variations" suite by Dan Tucker. This turned

out to be appropriate outdoor music for a relaxed crowd. The form was

loose, the style eclectic almost to the point of lost identity, but in

six minutes it managed to pay tribute not only to the classical tradition

brought over from Europe but also to such specifically American sounds

as big band jazz, Latin American dance rhythms and country fiddling. == From the review by Joseph McLellan in the

Washington Post, July 5, 1988

|

Tucker: No, not the ash heap, but I do think it has dug

itself into a blind alley. It was, in a sense, a negative, in that

it was getting away from things rather than creating things. It was

getting away from order, and sequence, and melody, and tonality.

It was a desperate effort to find some substitute for tonality, and in general,

I don’t think it succeeded. There were some

intriguing experiments along those lines — Boulez and Stockhausen,

for example — but it was an attempt

to find some rational principle which will solve all problems, very much

like Marxism. [Wistfully] I really have to be careful about this,

because some clown will think I am saying that serial music is communistic,

or something like that. I don’t mean that,

but they do seem to come from some common source —

an idea that at last we’ve found the

formula that will solve everything, and anyone who disagrees with it should

be done away with, or hushed, or ignored.

Tucker: No, not the ash heap, but I do think it has dug

itself into a blind alley. It was, in a sense, a negative, in that

it was getting away from things rather than creating things. It was

getting away from order, and sequence, and melody, and tonality.

It was a desperate effort to find some substitute for tonality, and in general,

I don’t think it succeeded. There were some

intriguing experiments along those lines — Boulez and Stockhausen,

for example — but it was an attempt

to find some rational principle which will solve all problems, very much

like Marxism. [Wistfully] I really have to be careful about this,

because some clown will think I am saying that serial music is communistic,

or something like that. I don’t mean that,

but they do seem to come from some common source —

an idea that at last we’ve found the

formula that will solve everything, and anyone who disagrees with it should

be done away with, or hushed, or ignored.© 1990 Bruce Duffie

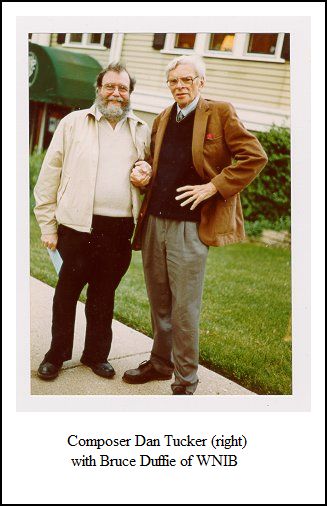

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on January 17, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB six weeks later, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.