|

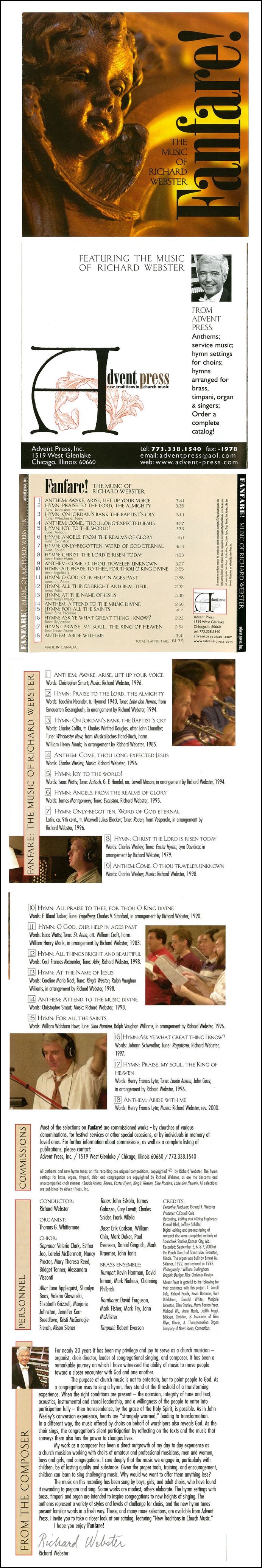

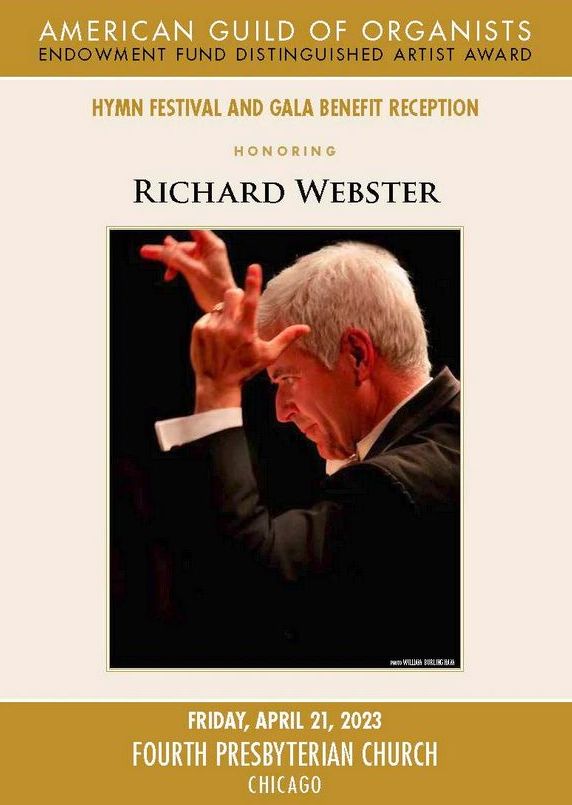

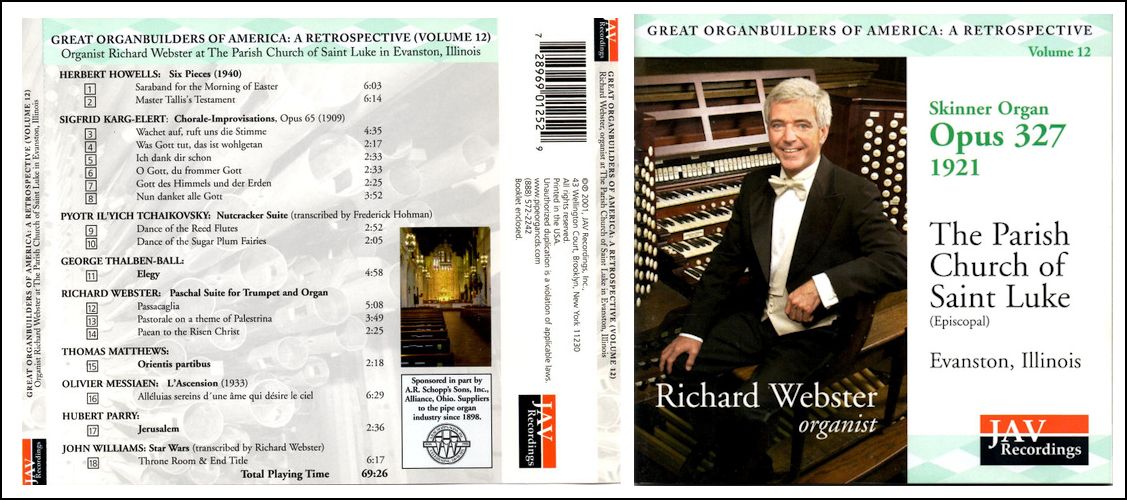

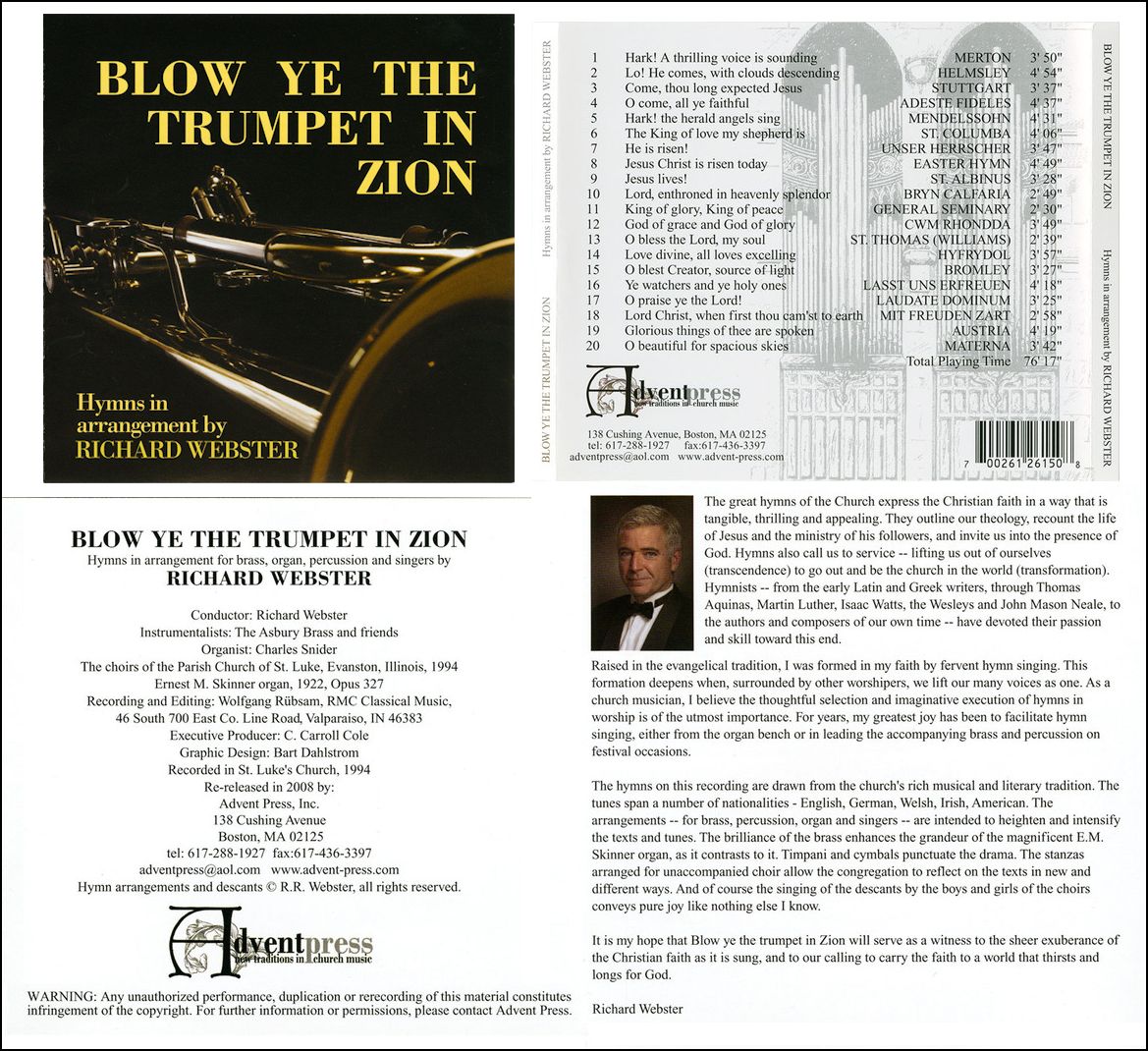

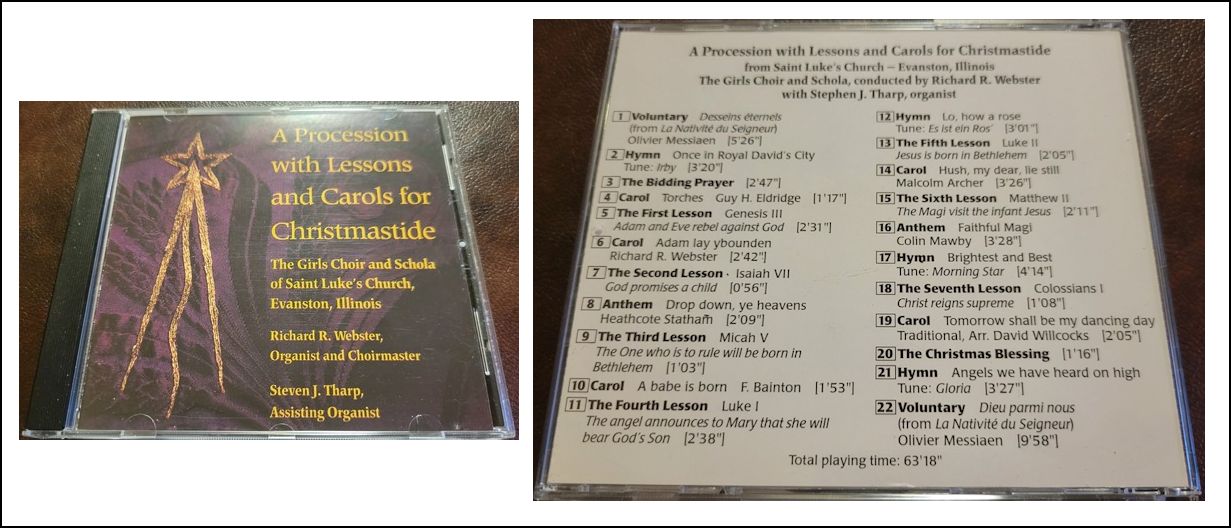

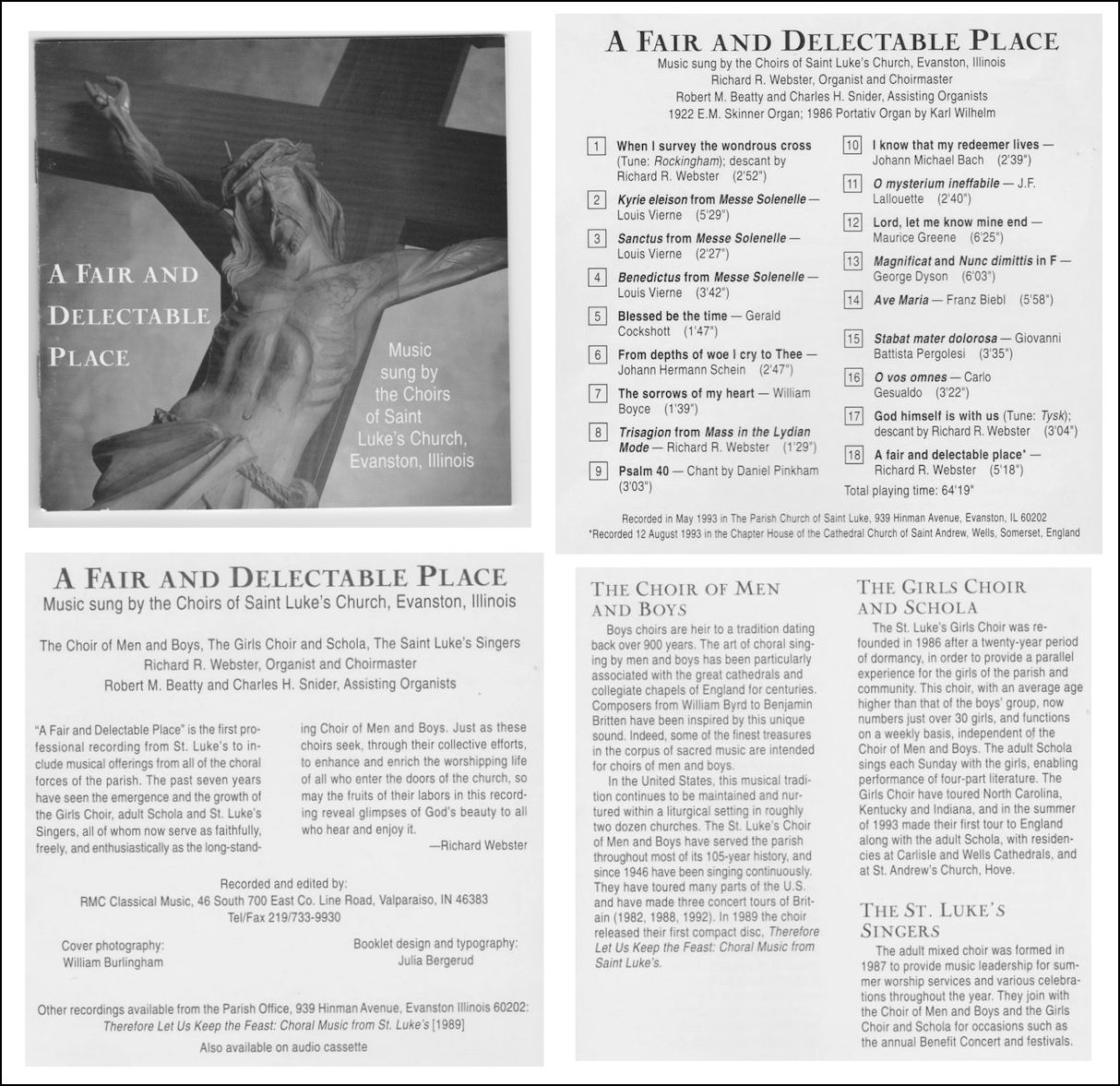

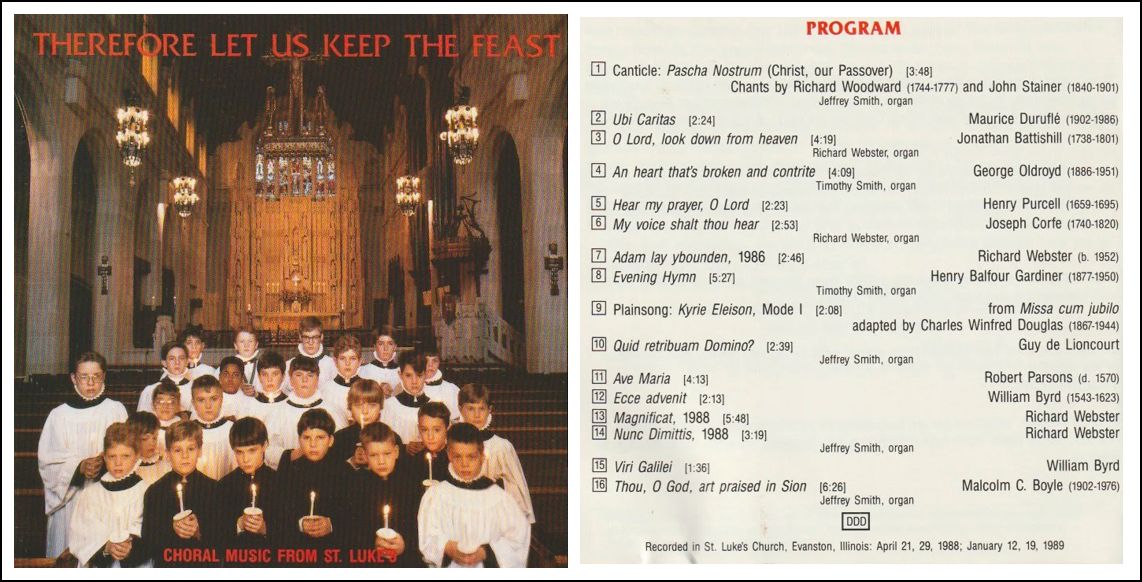

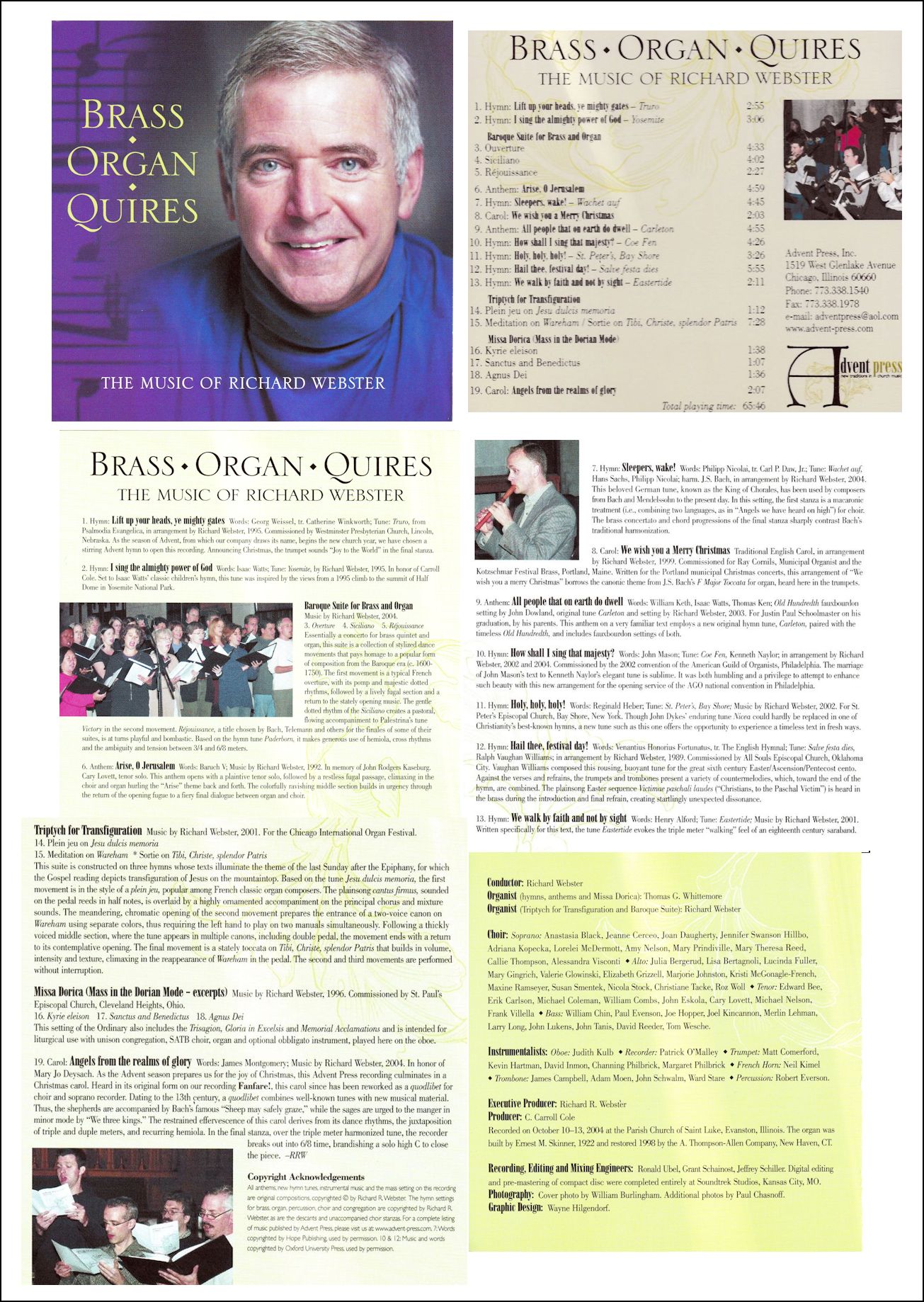

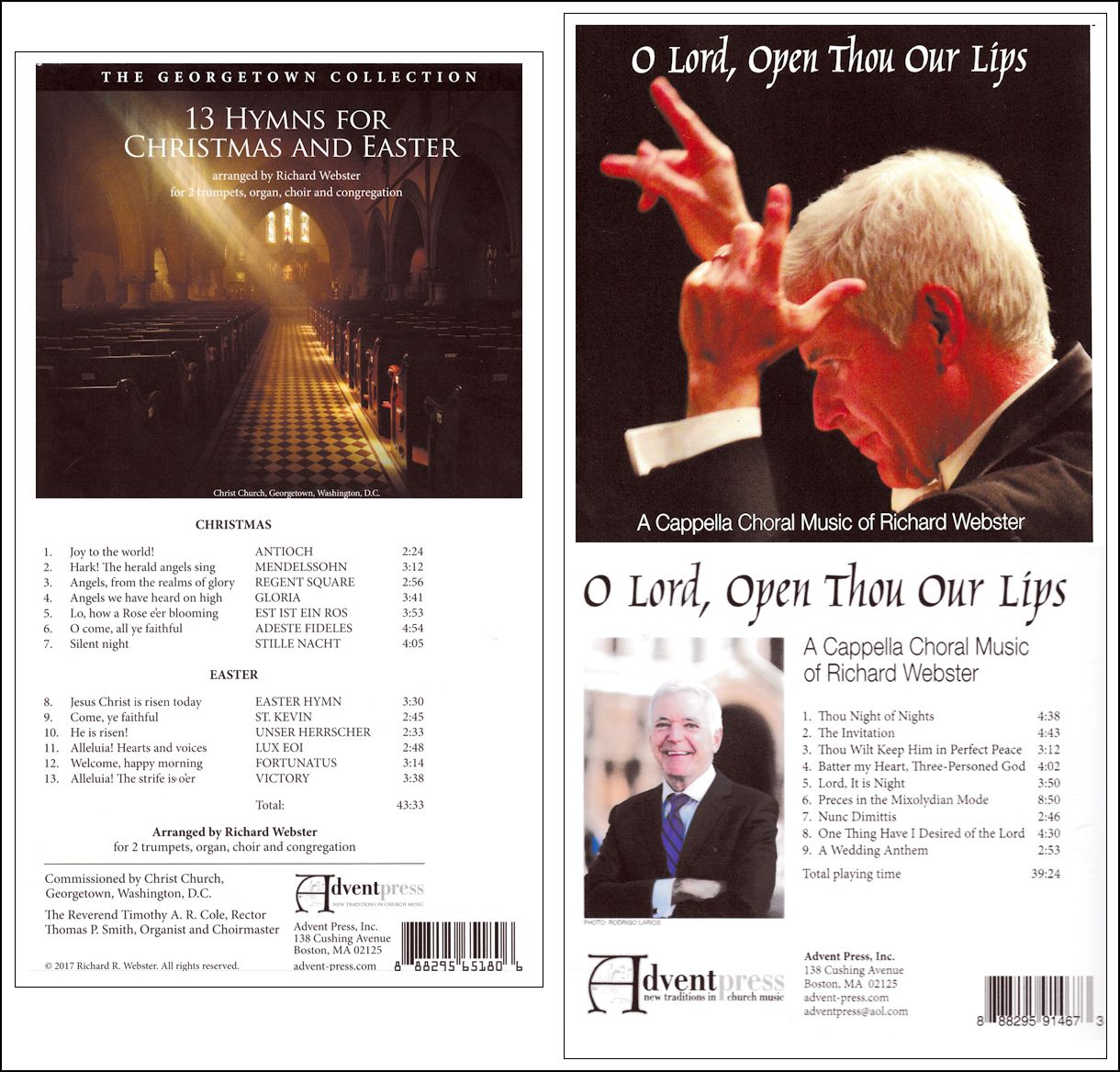

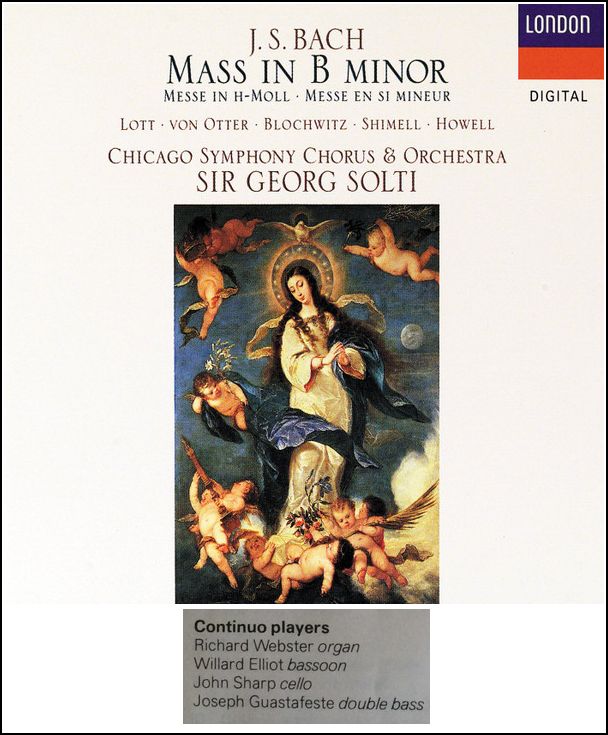

Composer, church musician, conductor and organist -- Richard Webster is currently Lecturer in the Institute of Sacred Music (ISM) at Yale University. He retired in 2022 as Director of Music and Organist at Trinity Church, Copley Square, Boston after 17 years. During 2023-24 he served as Interim Director of Music at St. Paul's Choir School, Harvard Square, Cambridge, Massachusetts. As a composer and arranger, he completes several commissioned works a year. His hymn arrangements for brass, percussion, organ and congregation are heard across the world, including the CBC's Christmas and Easter broadcasts, BBC's "Songs of Praise,” at a hymn festival in Sweden’s Lund Cathedral, in an Australian celebration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation and on a recording of hymns from Taiwan. At Trinity, Boston, where he cofounded the Trinity Choristers, he led the choirs on five tours of England, with residencies at York Minster; Westminster Abbey; Durham, Ely, Lincoln, Chichester, Salisbury, Wells, Winchester and St. Paul’s Cathedrals. During his tenure, Trinity's 1926 Skinner nave organ was successfully renovated and a new 4-manual Skinner replica console added. Richard is Music Director of Chicago's "Bach in the City," a new endeavor at St. Vincent DePaul Church, and the successor to Bach Week Festival that he had directed for 50 years, based in Evanston. Sought after as a choral clinician, he has led choir courses and workshops across the U.S., South Africa and New Zealand. He is an honorary Fellow of the Royal School of Church Music (FRSCM), and holds the Doctor of Music degree, honoris causa, from the University of the South at Sewanee. Webster has performed and recorded as organist with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in works from the Saint-Saens Organ Symphony to Ives' Fourth Symphony. He is the Organist and Choirmaster Emeritus of St. Luke's Episcopal Church in Evanston, Illinois, where, from 1974 to 2003 he directed the Choir of Men and Boys, the Girls Choir, Schola and the St. Luke’s Singers in a program widely respected and emulated. The restoration of the celebrated 1922 Ernest M. Skinner organ, Opus 327 at St. Luke’s was accomplished under his leadership. A native of Nashville, Mr. Webster studied organ with Peter Fyfe, Karel Paukert and Wolfgang Rübsam. He was a Fulbright Scholar to Great Britain, as Organ Scholar at Chichester Cathedral under John Birch. Webster's works are published by Augsburg Fortress, Church Music Society, Church Publishing, Selah and Advent Press. His articles on church music have appeared in The American Organist, The Diapason, Chicago Tribune, The Living Church, Journal of the Association of Anglican Musicians, the Choral Journal of the ACDA and the Windy City Times. He was a contributing author to Leading the Church’s Song, published by Augsburg. A passionate runner, Richard has completed 47 marathons, including 21 Boston Marathons. |

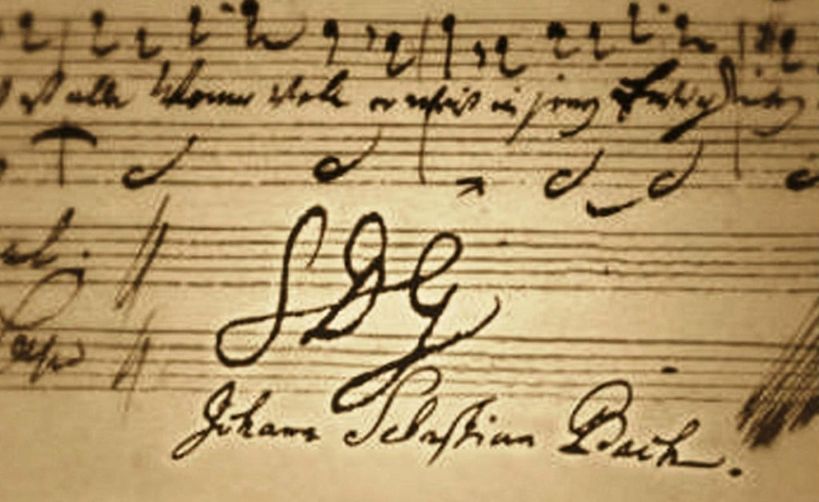

Johann

Sebastian Bach dedicated his musical works, both sacred and secular, to

the glory of God. He often inscribed the initials "S.D.G."

at the

end of his compositions, which stands for the Latin phrase "Soli Deo Gloria,"

meaning "Glory to God alone."

|

|

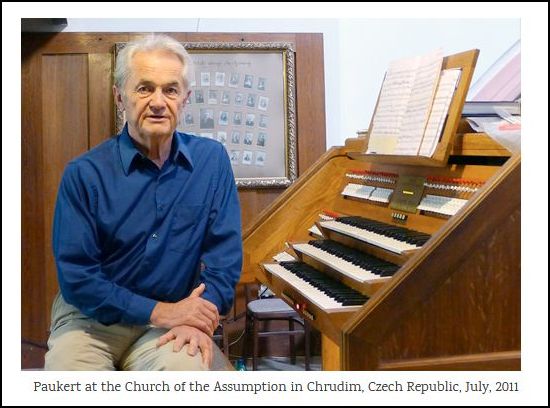

Karel Paukert was born in Skuteč, in what is today the center of the Czech Republic, on January 1, 1935. Karel was sent to gymnázium for two years in the nearby town of Chrudím, but was then sent back to the jednotná škola [vocational school] in Skuteč when this gymnázium closed, due to reform of the school system. He started playing oboe when he was 16 years old. In 1951, Karel was accepted at the Prague Conservatory, where he studied organ with Jan Krajs for the next five years. During this time in Prague, he also played in the orchestra at the Jiří Wolker Theater (today’s Divadlo Komedie.) After one year at HAMU (the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague) composing music for students of the school’s puppetry section, Karel was conscripted to the Czechoslovak Army in 1957. Because of his oboe playing, he was sent to Písek to become part of the army’s musical division. Karel said it was through his good references from the army that he was allowed to travel to Iceland in 1961, to become head oboist with the National Symphony Orchestra there. It was during a visit to Norway the following year that Karel decided not to return. He set out for Belgium, where he wanted to train with the organist Gabriel Verschraegen, but he was detained in Denmark for traveling without a visa, and had to spend months in Copenhagen waiting for an affidavit from the organist.Karel spent two years in Ghent before arriving in America in 1964. He studied for a doctorate in St Louis, Missouri, before accepting a post as professor of organ music at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. In 1972, Karel became an American citizen, and moved to Cleveland in 1974, where he began to work for the city’s Museum of Art. He retired in 2004, but continued to work as choirmaster and organist at St Paul’s Church in Cleveland Heights. He died April 30, 2025, aged 90.

|

See my interviews with Felicity Lott, Gwynne Howell, and Sir Georg Solti

© 1999 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in the studios of WNIB, Classical 97, on April 10, 1999. Portions were broadcast two weeks later, and again in 2000. Quotes were included in my article in City Talk magazine dated May 4, 2001. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.