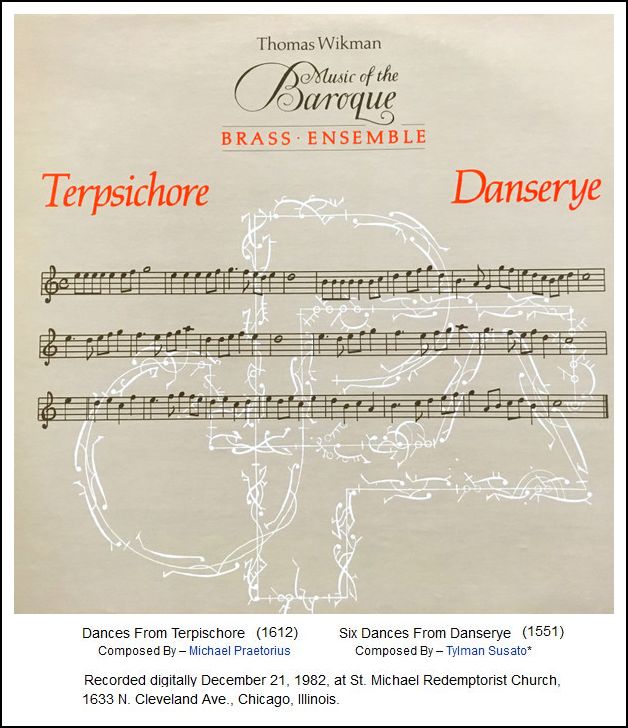

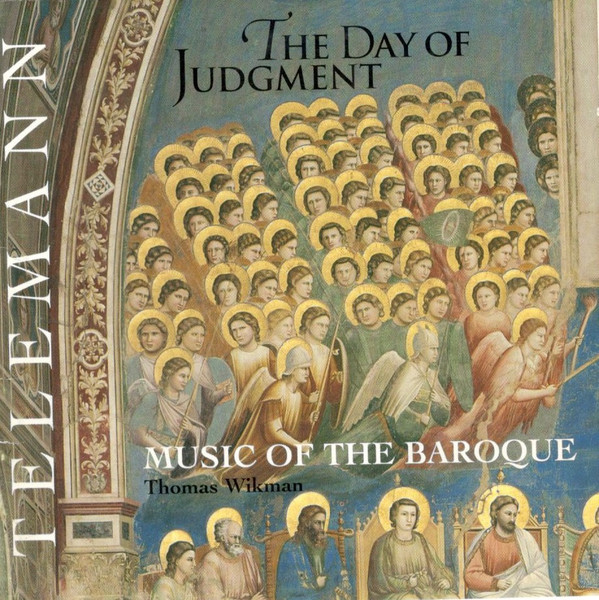

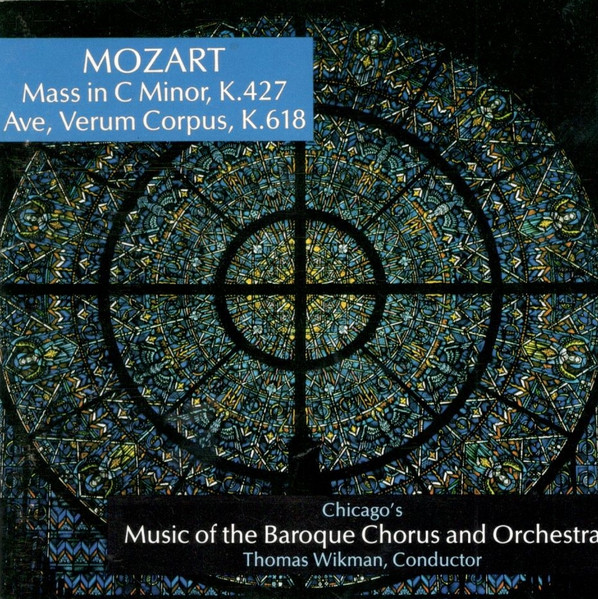

| Thomas Wikman is the primary featured artist in

the Richard and Judith Mintel Archive of Recordings. He has had an extensive

career as a choral and orchestral conductor leading hundreds of concerts

in repertoire from the Renaissance to the 20th century. Specializing in

the large choral/orchestral works of the 17th through 19th centuries, his discography includes

numerous CDs, among them a critically-acclaimed Monteverdi Vespers

of 1610.

From 1974 to 1991, he performed large-scale Romantic and 20th-century repertoire with two other groups: the Elgin Choral Union, and the New Oratorio Singers which he founded. He explored Renaissance repertoire with his two small professional ensembles, the New Court Singers and the Tudor Singers. He has appeared as conductor, organist, and harpsichordist with The Ravinia and Grand Teton Music Festivals. Mr. Wikman maintained a voice studio, producing vocalists who have performed roles at the Metropolitan and Chicago Lyric Operas, San Franciso Opera, and New York City Opera and the major European Houses, including LaScala, Bayreuth, Vienna, and Berlin. As a pianist, Mr. Wikman regularly accompanied singers in recital including Isola Jones, Frank Guarrera, Simon Estes, Judith Nelson, Tamara Matthews, Patrice Michaels, Richard Versalle, and Gloria Banditelli. An active organist who has played over 600 recitals, Wikman was the Artistic Director of the Paul Manz Organ series for the Lutheran School of Theology in Chicago, and he was the organist and Artist-in-Residence at the Chicago Theological Seminary where he played weekly recitals. He has toured Europe seven times as an organist playing recitals in France, Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, Denmark, and Italy. Highlights include recitals at The Friars’ Basilica in Venice; Saint-Sulpice, Paris; and The Royal Castle at Hillerod, Denmark. He has made numerous appearances on the Flentrop organ at the Busch-Reisinger Museum, Harvard University. In May 2002, he was awarded the degree of Doctor of Fine Arts (Honoris Causa) from the University of Illinois at Chicago for “making an incomparable contribution to the musical life of Chicago.” As Choirmaster of Church of the Ascension, Mr. Wikman conducted the professional choir there in more than 1700 worship services replete with masterpieces from the year 1000 A.D. to the present, including pieces by Orlando di Lasso, de Victoria, Palestrina, Bach, Mozart, Schubert, Haydn, Liszt, Brahms, Herbert Howells, Leo Sowerby, and Ralph Vaughan Williams. Born in Muskegon, Michigan, Mr. Wikman was given a rigorous musical

education from an early age. He began composing and playing the piano

at age five, and was soon performing frequently in public. At age seven,

he began formal training with composer Carl Borgeson, studying composition,

harmony, form, and analysis, counterpoint and orchestration. Throughout

his early years in Michigan, he was active in both amateur and professional

circles as a composer, pianist, trombonist, organist, and church choir director.

As a young man, he continued his musical studies in Chicago primarily with

Leo Sowerby and also with Stella Roberts, Jeanne Boyd, and Irwin Fischer.

He studied organ and Gregorian chant with Benjamin Hadley and others; he

studied voice with Don Murray and Norman Gulbrandsen. == Biography (slightly edited, and photo added)

from mintel.org |

| minuet, (from French menu,

“small”), elegant couple dance that dominated aristocratic European ballrooms,

especially in France and England, from about 1650 to about 1750. Reputedly

derived from the French folk dance branle

de Poitou, the court minuet used smaller steps and became slower and increasingly

etiquette-laden and spectacular. It was especially popular at the court

of Louis XIV of France. Dancers, in the order of their social position,

often performed versions with especially choreographed figures, or floor

patterns, and prefaced the dance with stylized bows and curtsies to partners

and spectators. The basic floor pattern outlined by the dancers was at

first a figure 8 and, later, the letter Z.

Musically, the minuet is in moderate triple

time (as 3/4

or 3/8)

with two sections: minuet and trio (actually a second minuet, originally

for three instruments; it derives from the ballroom practice of alternating

two minuets). Each consists of two repeated phrases (AA–BB), but the

repetition may be varied (AA′–BB′). The overall form is minuet–trio–minuet.

The minuet frequently appears in 18th-century suites (groups of dance

pieces in the same key), and in Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni onstage

musicians play a minuet at the close of the first act. Typically, the third

movement of a Classical chamber work (e.g., string quartet) or symphony is a minuet. In most of his symphonies Beethoven

replaced the minuet with a scherzo (although he did not always use that

term as a designation for the movement), similar or identical in form but

much faster and more exuberant. Neoclassical examples of the minuet include

Johannes Brahms’s Serenade No. 1 for orchestra, Opus 11 (1857–58),

and Arnold Schoenberg’s Piano Suite, Opus 25 (1923). * * *

* *

basse danse, (French: “low dance”), courtly dance for couples, originating in 14th-century Italy and fashionable in many varieties for two centuries. Its name is attributed both to its possible origin as a peasant, or “low” dance, and to its style of small gliding steps in which the feet remain close to the ground. Danced by hand-holding couples in a column, it was performed with various combinations of small bows and a series of walking steps completed by drawing the back foot up to the leading foot. The music was in the modern equivalent of 12/8 time. The basse danse was typically followed by its afterdance, the saltarello. |

BD: Why did you abandon that?

BD: Why did you abandon that?

© 1997 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on July 20, 1997. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following month. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.