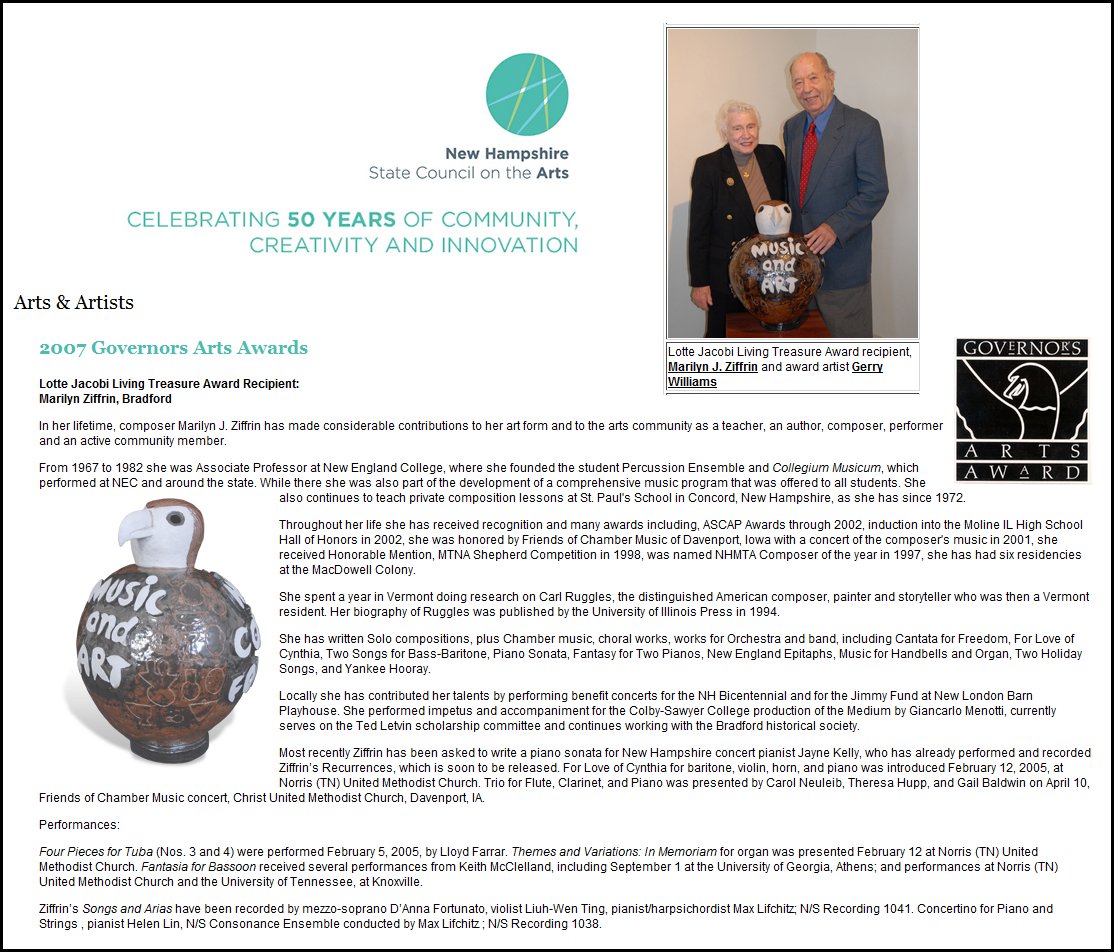

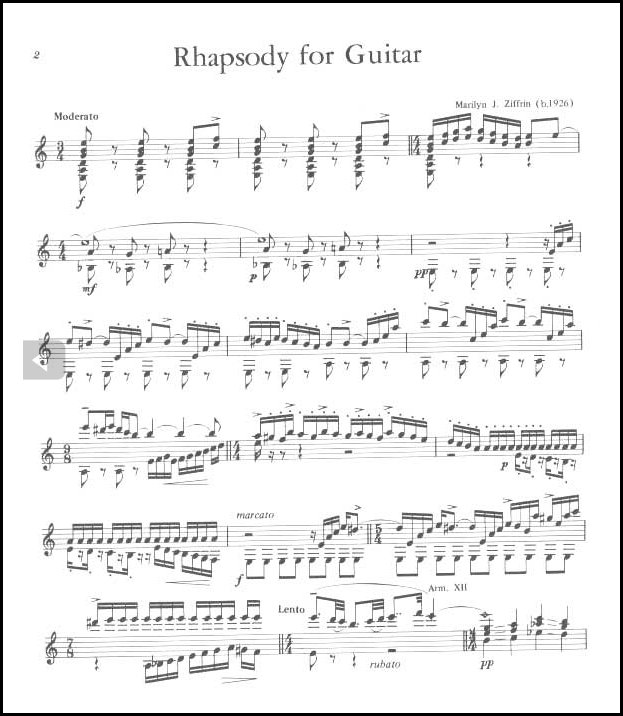

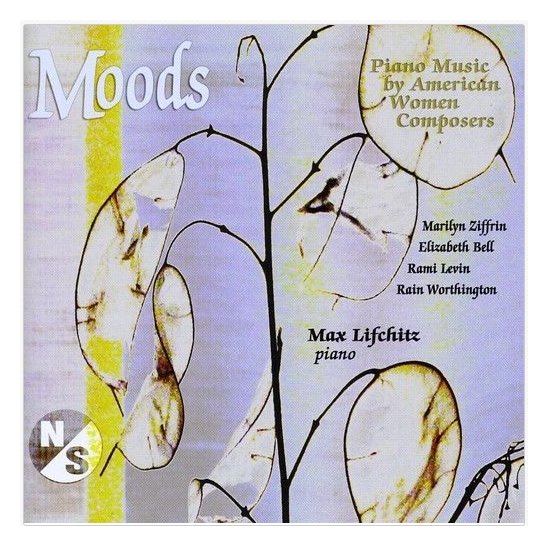

Composer / Author Marilyn J. Ziffrin

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

At the end of June of 1994, Marilyn Ziffrin returned to Chicago, and she

graciously took time from her schedule for a conversation. We spoke

of her music and ideas, as well as her other area of study, the composer

Carl Ruggles.

Bruce Duffie: How did

you happen to decide to leave Chicago and go to New Hampshire?

Marilyn J. Ziffrin:

Well, two reasons. One of course was Carl Ruggles. I wanted to

spend time with him, and I did. I spent a year with him. The

other reason was even more important in the long run. I had the feeling

that, as a composer, I should go East. I had this mistaken conception

that if I moved to New Hampshire, I would be close enough to the metropolitan

areas of both Boston and New York, that I would be able to get down there

very easily.

BD: I take it that didn’t work out?

BD: I take it that didn’t work out?

MJZ: No, as a matter

of fact, it did not! But, in fact, there was another reason.

I was accepted at the MacDowell Colony. My first visit was in 1961,

and I really did fall in love with New Hampshire. It is exquisite country,

and I had the idea of settling out there in the peace and quiet of the countryside.

I felt simply at home, and there are a lot of artists who had done the same

thing — not necessarily

in music but painters and so forth.

BD: Is it particularly

conducive to the creative juices that have to flow?

MJZ: In truth the

answer I have to say is no, because you work a great deal in isolation.

But it is true that you can get to Boston — in my case

from where I live in about ninety minutes — and so

I do get down to the Boston Symphony a great deal. It is also true

that I can get to New York in an hour and a half on the airplane, or even

drive down in about five or six hours. And it is at least close enough

to commute by train. But I had the feeling that I simply had to move

on from Chicago and try out new territory, and this was a territory that

felt most congenial. I have simply always loved the East from the time

I was a kid, and I had the feeling that this was where I belonged, and I’m

not sorry I moved. I was born in Moline, Illinois, and still have close

relatives there. My brother’s there, but I just think I’m an Easterner

at heart. I don’t quite know what that means, but I’ve always felt

comfortable in the East. Composition, in any case, is a solitary activity,

and you can write it anywhere.

BD: So you can

choose exactly where you wish to settle down?

MJZ: Precisely!

I had taught here, and I wanted to move on to teach somewhere else.

I just had this feeling that it was time to try somewhere else, and the natural

place for me was to go east.

BD: Is the music

that you write your music, or is it influenced by whether you are in Chicago

or in New Hampshire or in Timbuktu?

MJZ: Oh, that’s

an easy question to answer! It’s mine, it’s absolutely mine!

I’m influenced by the music I hear, I’m sure, and by the music that I have

studied. I’ve studied a lot, but it would be the same if I lived in,

as you say, Timbuktu. It would still be me! So I think you’re

right — you just pick where you want to live and write

the stuff.

BD: So you’re influenced

by what you hear, but not so much by the green around you or the concrete

around you?

MJZ: No, I don’t

think so. It’s what I hear and what I had heard. I try very hard

to hear a lot of music. In New Hampshire you don’t hear very much live,

but you do by public radio. I probably could not live there if I did

not have access to public radio. We have in New Hampshire only one professional

symphony orchestra but where I live I can get three different public radio

stations — Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine

— so I have access to an enormous amount of music. And then,

as I say, I get to Boston within an hour and a half.

BD: On the radio,

do you pay particular attention when new pieces are being played by symphony

orchestras or chamber groups?

MJZ: Yes, exactly.

I subscribe to all three, get program guides, and if there’s a new contemporary

piece, or even a contemporary piece that I think I even know, I make a point

of being around to hear the piece and really listen. A lot of people

put the radio on and they don’t listen, but I listen!

BD: Do you get

a lot out of re-hearing pieces you know?

MJZ: I certainly

do. Often times symphony orchestras will pay their nod to the twentieth

century by doing something by, say, Stravinsky. I know Stravinsky a

little bit, but I also listen to that, too. Without that access it

would be very hard to live in New Hampshire but with it, it’s great, it’s

wonderful.

BD: Do you also

listen to Haydn and Beethoven and Schubert?

MJZ: Oh, indeed.

Beethoven and Haydn particularly are probably very great influences on me,

and have been for years. I studied for an advanced degree in musicology

at the University of Chicago, and one of my major professors was probably

one of the greatest teachers I ever ran into, a guy called Grosvenor Cooper,

who was a Beethoven specialist, and that mattered very much to me.

BD: Do you feel that your own music is part of a

lineage of composers and compositions and styles?

BD: Do you feel that your own music is part of a

lineage of composers and compositions and styles?

MJZ: Yes, I do.

I think my music is in the tradition. We’re not talking now in terms

of whether I am as good or as bad as they are, but yes, I don’t think

my music is out of the tradition.

BD: You live on

their street?

MJZ: I think so,

yes. My music sounds like the century in which I live, and I would

not want it to sound any other way, but it’s also within the tradition.

I’m one of those people who believe in structure very much, and while I certainly

experiment with sounds and use what other people might call dissonances and

modern harmonies, it seem to me it’s very much in that line.

BD: When you’re

writing a piece and putting some notes on paper, are you always controlling

what goes on the page, or are there times when you see something on the page

and you don’t know where it came from?

MJZ: It’s a very

good question! There are always surprises. I have described being

a composer very much like being an athlete. You get in training as

an athlete and when you’re composing you spend so many hours a day doing

your composition, your thing. When you’re in training, the wheels are

greased and it moves, and when it moves sometimes you don’t know where it’s

going and you are indeed surprised. Then you have to be your own worst

critic and use an eraser as well as a pencil, and that’s dreadfully important.

Then this is one of the joys — as performers take up

your piece, they will find things you didn’t know you had put in. As

they make the music their own, they don’t change the notes, don’t misunderstand

me, but they discover things that you didn’t know were there. If the

piece is good, it has that quality so that the same piece can be played by

many different people and have different interpretations. That’s really

one of the great joys.

BD: Do you purposely

build in this leeway, or is it just automatically there?

MJZ: It’s automatic.

If you’re in training and it goes well, it gets in there and I have no idea

how. For me, this is one of the tests of whether a piece works or not.

If it works, then it will have that quality, and you may not even know it

exists. In fact you can’t know it. That ability to move around

within those parameters does not happen until the performers take it.

BD: Do you know

as you’re writing it whether it’ll work or not?

MJZ: Oh, yes!

That is the mark of a good composer — to be your own

worst critic. Yes, you have to know if it’s going to work. If

you don’t know that much about a piece, then you have some studying to do.

BD: Studying of

technique?

MJZ: Studying of

technique, self-study, studying of what you’ve done. You really have

to stand back every day and understand what you did yesterday is either good

or bad, or has possibilities. I’m very, very serious about the use

of an eraser. You have to willing to know you thought it was wonderful

yesterday but today we have to erase it.

BD: It wouldn’t

be back to being wonderful next week?

MJZ: If you really

feel it’s no good, it won’t get back to being wonderful. If you’re

not sure, give it a chance, but if you really know the next day it’s no good,

get rid of it. You can’t fall in love with your own stuff. You

have to stand back and know if it is good or bad. You can make a judgment.

This is terribly important. I had a teacher who said that everybody

can learn to be an acceptable composer. There are rules just like there

are rules of writing poetry and so forth, and if you study long enough, everybody

can do it. Everybody gets ideas. People sing in the shower, and

those are motives. Those are nice little tunes and things that may

be their own. Techniques will teach you that, and then the X quality

comes in. But as a composer, you have to be able to know what you did

and that there are flaws, and maybe you can fix the flaws. If you can’t,

is the piece still good enough to stand on its own two feet? If it

isn’t, then you have to get rid of the piece!

BD: Just completely

toss it out?

MJZ: It’s been

done! [Both laugh]

BD: When you’re

working with the piece and tinkering with it and you have all of the notes

down and you’ve fussed with it, how do you know when it’s ready and when

you can give it away?

MJZ: Oh, that’s

the best question of all! If you think I know the answer, you’re wrong.

I don’t! I once asked a poet how he knows when a poem is over, and

he said, “When they take it away from me!”

[Both have a huge laugh] I don’t know. I write syntactical music,

music where one thing follows another and follows another and follows another,

like language. There are other ways to write music, like music of chance

or aeleatoric music where you don’t have that thing. But mine is syntactical,

therefore you set up certain sound expectations as you write. One seems

to know the piece is over when those expectations have been fulfilled, so

I suppose that’s a technical way in which you know. Another way is

that they take it away from you! In all truth, one is never totally

satisfied with the piece. Every piece has certain flaws, and it’s just

that you know that you’ve done the best you can at that moment. You

hope nobody else knows that those flaws are there, and if you’re honest with

yourself you think that even if I didn’t do so well at this point, this is

the best I can do now. When I do the next piece, I won’t make that

same mistake.

BD: Is it even

humanly possible to write a piece without flaws?

MJZ: I personally

do not think so, but of course when I look at somebody like Bach, for example,

I wonder. Not Beethoven because I can point out flaws in Beethoven.

Bach is a little more problematic. Maybe he did, I don’t know.

I don’t think so.

BD: I was going

to nominate Mozart...

MJZ: This is fair,

yes. In today’s world maybe there are composers who think they’ve written

pieces without flaws? I would certainly be the last one to say that

about my own music.

BD: Without naming

any names, do we have composers either writing today or recently who are

on the level of Bach and Mozart and Beethoven?

MJZ: [Pauses a

moment] I don’t know. I don’t this is a fair question because

they lived so far back and we could look at their work as a whole, study

it over so many years, and study their techniques with no emotional baggage

that we’re carrying looking at it.

BD: In other words,

the most recent music that we can study now would be, maybe, Debussy or early

Stravinsky?

MJZ: Exactly!

I may be wrong on this but I don’t see towering figures on the landscape today.

I see good composers, don’t misunderstand me. I can only speak about

my heroes of the twentieth century who are ones who have passed away already

such as Benjamin Britten and Charles Ives.

BD: Carl Ruggles

too?

MJZ: I have mixed

feelings about Carl as a composer. As a man there is no question that

I have very strong feelings about him. I loved him and I hated him

also at the time sometimes! I think Carl managed to write probably

a masterpiece in the Sun-Treader,

but almost all of the other pieces have flaws. Though he certainly

had a lot of it, his lack of training and his lack of self-criticism and

his inability to criticize too seriously for too long at time probably didn’t

help him.

* *

* * *

BD: We’ll come

back to Ruggles a little later. I want to mostly talk about you and

your music first. You were saying that you can’t really fall in love

with your own music. Once it is out there and published and is no longer

part of you, then can you fall in love with it?

MJZ: [Enthusiastically]

Oh indeed, absolutely! You certainly can... in fact one does.

It’s fun to go back and listen to your music you’ve done, say, ten or fifteen

years ago. You listen to it and you know that it stands up. There

are some weaknesses, but you’ll stand by it, and that’s fine. It’s fun,

but you dare not do that while writing the piece. I’m quite serious

about this. You absolutely dare not do that while you’re writing the

piece. You really have to be very critical. You will like certain

things, and some things work when the juices are flowing. You come

back to it two or three days later and you think this really works, and there’s

this enormous sense of satisfaction. But if the piece isn’t

over, at the same time you have that sense of satisfaction you

also have this terrible sense of having to do something that matches it!

That’s a tough thing. I’ve often said there’s nothing quite so frightening

as an empty sheet of music paper. What do you put down on it?

Where do you go from there? And that’s scary!

BD: Is it as scary as having a full sheet of music

paper and you don’t know whether to let it go or still play with it?

BD: Is it as scary as having a full sheet of music

paper and you don’t know whether to let it go or still play with it?

MJZ: The empty

sheet is scarier. If you have the full sheet and you have really good

critical faculties, you’ve got some hints on where to go. But an empty

sheet has no ends. In my case, once something is down, if it has validity

there are within it suggestions of where to move. The issue is whether

I am smart enough to let the music tell me where to go. If there’s

nothing down there, then I’m in trouble! [Both have a huge laugh]

BD: Ohhhh, but

I’m sure you are able to surmount the trouble!

MJZ: Well you have

to. It’s one of the ways where you separate the pros from the amateurs.

You have to, and you do.

BD: Are the pieces

you write on commission, or are they things you just have to write?

MJZ: It’s a combination

of both. I’ve been doing it for so long that I’m happy to say a lot

of commissions are coming in. People are asking me to write the music,

but there are things to write whether anybody commissions them or not,

on the hopes that I will find performers who would be interested in playing

them. So at the moment it’s a nice combination of the two.

BD: Do you work

on more than one piece at a time?

MJZ: No, no.

Just one. I’m not one of those people who can deal more. There

are composers who can handle more than one piece at a time, but I can’t.

I’m too concentrated. It’s got to be that, and then I move on to the

next.

BD: When you’re

working on a piece, do you work on it every day?

MJZ: Yes, every

day possible. If I have to take a trip or something, then of course

I don’t. But if I’m home, the answer is yes, Saturdays, Sundays, Mondays,

the whole bag. I usually work in the morning. I’m a morning person.

BD: You don’t bring

it with you on trips and maybe tinker with it on vacation?

MJZ: No, but I

think about it a lot.

BD: Let it steep?

MJZ: Yes, and that’s

very good. But when I’m at home, it’s really quiet every day.

BD: Is there a

time, even when you’re at home, that you should put it aside for three days?

MJZ: There probably

is a time when I should, but mostly I just deal with it. Life itself

interferes in terms of those two or three days. There are always do-days

and social engagements and so forth, that sometimes will mean I’m not going

to be able to work tomorrow. So there are interferences like that.

But on the blotter I work regularly.

BD: When you get

a piece finished, you can set it aside or give it to whoever has to take

it from you. Do you plunge into the next piece right away, or do you

give yourself a little bit of a break?

MJZ: I generally

try to give myself a small amount of break, but again it depends. If

I have more work that is piling up on me, then I may plunge right in.

But one works when even when one isn’t working, if you know what I mean.

If you’ve got something on your mind, it churns by you walking down the street

or grocery shopping or whatever. So you do work even when you’re not

working! While often times I would take a break from one piece to the

next, there are times when I don’t have to. It really depends on whether

somebody is out there waiting for it, whether it’s up to me, and what life

will do.

BD: When you start

working on a piece, are you aware of how long it will take to compose?

MJZ: No.

That can be a bit of a problem. What I always try to do is give myself

more time than I think it will take. I’m usually wise to do that because

so far I’ve always been able to meet all my deadlines without any problems.

I wouldn’t like to have to write something in a hurry. I’m sure this

doesn’t hold for other people, but in my case, forcing something would make

it turn out to be less well done than I could do it.

BD: Do you know

when you’re starting about how long it will take to perform?

MJZ: That’s a parameter

I make ahead, yes. For example, the piece I’m working on now is a clarinet

concerto, and when I was asked to do this, I was told that they wanted a

work around 15 or 16 minutes. Already I have that parameter.

BD: So if it becomes

14 or 17, it’s all right, but if it goes to 22, it’s too much?

MJZ: Exactly, and

on that basis I can move ahead.

BD: Will there

ever be a time, though, when it just has to be that 22 or 24 minutes?

MJZ: Oh, sure!

Then you get yourself into real trouble!

BD: Do you write

a different piece and not give them that one?

MJZ: I guess...

I don’t know. It hasn’t happened with me. I start out with certain

parameters, and in this case it’s the soloist versus the orchestra, and it’s

that length. I arbitrarily decided it was going to be a three-movement

work. I was not going to have a cadenza in the first movement because

everybody has a cadenza in the first movement. I’m going to delay it

to the opening of the second movement. All these things are a result

of simply sitting down and trying to figure what the parameters are.

I haven’t had that problem of writing a piece that extends beyond, or a piece

that’s too short. There is that famous story about Stravinsky.

When the city of Venice commissioned a work from him to open up the Teatro

Fenice, it turned out to be a very short piece. They wired that because

they were paying him so much for it, it should longer. He cabled back

and said, “I could make it longer, but I couldn’t make

it better!”

BD: Good answer!

MJZ: Wonderful!

But I haven’t run into that so far. I guess I’m just one of those plodders

who do what they tell you to do, which is fine. I have no arguments

with that.

* *

* * *

BD: Let me ask

you the big philosophical question. What is the purpose of music?

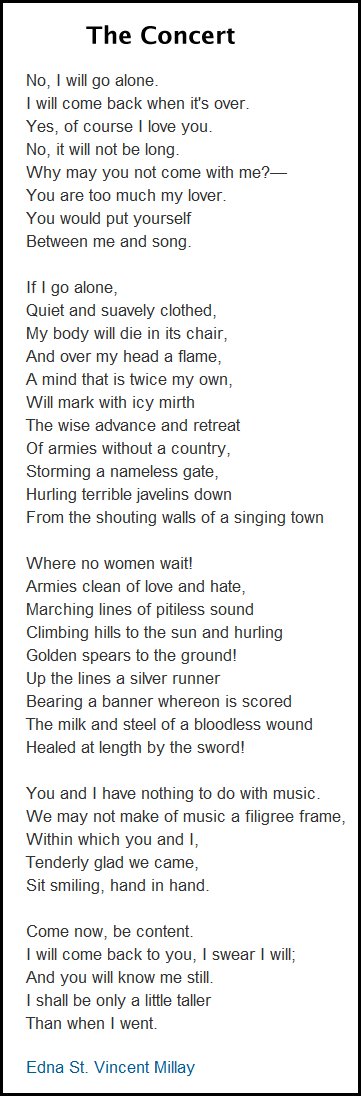

MJZ: [Thinks a moment] That’s a biggie!

I could answer you with an equally philosophical statement, “Man

does not live by bread alone!” I really do think

every human being, whether they choose to admit it or not, has an inner life,

and it seems to me that music, serious music, deals with the human inner life,

not the outer life. It won’t make you richer by any means but

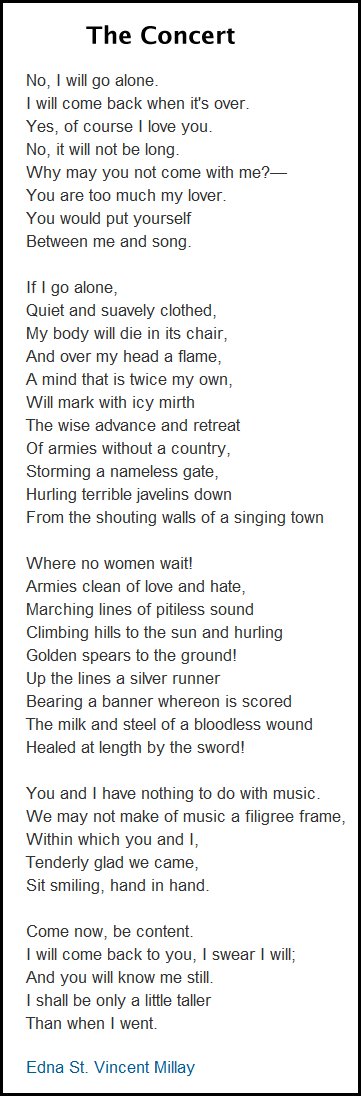

it will make you bigger. There’s a wonderful poem by Edna St. Vincent

Millay called The Concert, in which

the woman is talking to her lover and she says, “Do

not go to the concert with me,” because she wants to

go by herself to hear the music and not be distracted by the man she loves.

But she says, “Don’t worry, I’ll come back to you,

but I will come back taller.” I think that’s

the purpose of music. I would even go so far as to suggest it’s probably

the purpose of art, and that ain’t a bad purpose!

MJZ: [Thinks a moment] That’s a biggie!

I could answer you with an equally philosophical statement, “Man

does not live by bread alone!” I really do think

every human being, whether they choose to admit it or not, has an inner life,

and it seems to me that music, serious music, deals with the human inner life,

not the outer life. It won’t make you richer by any means but

it will make you bigger. There’s a wonderful poem by Edna St. Vincent

Millay called The Concert, in which

the woman is talking to her lover and she says, “Do

not go to the concert with me,” because she wants to

go by herself to hear the music and not be distracted by the man she loves.

But she says, “Don’t worry, I’ll come back to you,

but I will come back taller.” I think that’s

the purpose of music. I would even go so far as to suggest it’s probably

the purpose of art, and that ain’t a bad purpose!

BD: Of course not!

What advice to you have for younger composers coming along?

MJZ: I would say

to the young composers, work , work, work, and don’t be discouraged.

You may or may not make lots of money, but the joy is in the doing, and it

really is a joyful endeavor. If you make it your life, you will know

great, great joy. You may be poor, you may be rich, it doesn’t

really matter. The act of composing is really very thrilling because

you’re creating something. There aren’t very many people who do that.

It’s really a wonderful thing.

BD: You say you’re

creating. Are you creating something out of nothing, or are you creating

something out of something?

MJZ: You’re creating

something out of something. You don’t do it in a vacuum. What

you do is you hear all kinds of sounds — sounds of

streets, sounds of jazz, all kinds of musics and all kinds of sounds.

Then, if you have that creativity within you, and the guts, and the stick-to-it-ness,

and all the rest of it, you take all of that and it gets mingled with your

personality and comes out sounding like you. I don’t think it comes

out of nothing, I really don’t. It has to come out of other sounds.

But they can be all kinds of sounds. They don’t have to be any one kind.

BD: At least from

what I’ve been able to hear, you have consistently written music that derives

from tonal centers. Are you glad that we seem to be coming back to that

in a general sense? We seem to have lost it in the ’60s...

MJZ: Yes, that’s

interesting. There are my conservative friends and they’re not tonal

sinners. There are moments of stability to which one comes back, gestures

of stability they would say, and yes, I think it’s good. I also think,

though, that it’s very hard to be a composer in today’s world because there

are so many possibilities. It was much easier when you had one style,

when Beethoven and Mozart were around. Bach already moved a little

bit because he had the modes and he moved into the major-minor system.

But there were preconceived notions of what classical music would sound like,

so the composer knew that ahead of time and wrote in that style. He

didn’t really have too much to worry about, whereas today’s

serious composer has so many possibilities. There’s minimalism, there’s

neo-romanticism, there’s electronic music, there’s you name it, there’s so

many styles. And no matter how difficult it is for the composer, it’s

also very difficult for the listener. A listener goes to a concert,

and unless he knows the composer’s music ahead of time, he or she has no

way of knowing what to expect. When the composer sits down, there are

so many styles to choose from, so what you do? You ultimately have to

be true to yourself and do whatever comes out, but for a young composer it

may indeed be very difficult situation. I have fortunately gone beyond

that, but I can see that it’s not in any way an easy time.

BD: You say the

composers back then only had one style. Didn’t Beethoven push that

style along, and develop it, and didn’t Wagner especially

change it?

MJZ: Yes, but by

the time Wagner came along, he did romanticism to death. They had to

change it. There was absolutely no place else to go. But

take a composer like Mozart. There was the sonata allegro form, and

he had his some of his students finish his movements for him, because...

BD: ...it could

only go one way?

MJZ: Yes.

You had a first theme in the tonic and the second theme in the dominant,

and then you had the development section. Of course, Mozart would do

that, but by the time you’d get back to the recapitulation, both themes had

to come back and both themes had to come back in the tonic so you could end

the piece. So he could give them to an advanced student and have him

finish it. We can’t do that today! You don’t have the certainty.

Also, in those days when the audience went to a concert, they knew what to

expect. Don’t misunderstand me, they could marvel at the genius of

these people who were able to work within this set of parameters that everybody

knew and still write absolutely write incredible and glorious music.

But they knew from when they sat down what the parameters were. Now,

somebody in the audience sits down and will wonder what she’s going to hear!

BD: Are the parameters

out there, or are there no parameters?

MJZ: Precisely

the point! There are none. Each piece has to set its own, or

each composer has to set his or her own parameters. So if you don’t

know the previous music of the composer when you go into the concert hall,

you really have to have a totally open mind.

BD: I think that

even if you knew the previous music of the composer, you’d still have to

have that open-ness.

MJZ: Precisely.

BD: So what advice

do you have for audiences then — just come with open

minds?

MJZ: Yes, and that’s

such a stupid statement to make because obviously it’s very difficult, but

yes indeed. They have to. It seems that they are quite willing

to accept the visual with an open mind. Those who go to art galleries

and to different painting shows look at paintings by artists whom they don’t

know, and again whose parameters they do not know, but they can see it at

a glance. They can see the whole. Music can’t be observed like

that! So it’s harder.

BD: It has to unfold

in its own right?

MJZ: That’s right.

It’s a time art rather than an instant kind of thing like that.

BD: Don’t you think

there are visual artists who wish that people would linger a little more

than just glancing at it and hoping that they take it all in?

MJZ: No question

about it. I’m being facetious about that because clearly if you really

want to look at a painting you have to stand and look at it and study it.

But yes, my advice to an audience would be to come with an open mind, understand

that the composer has worked very hard to create this sound structure, and

he or she expects you to work that hard to get it, instead of just sitting

there and letting it flow over your while you think about something else.

BD: This brings up a balance point. How much

is artistic achievement and how much is entertainment value either in music

in general or in your music?

BD: This brings up a balance point. How much

is artistic achievement and how much is entertainment value either in music

in general or in your music?

MJZ: I don’t write

music to be entertaining. I write music to make a statement.

I don’t know what the statement is. I know that sounds facetious, but

if I could put it in words clearly I wouldn’t write music. But I don’t

think the purpose is to be entertaining. On having said that, I immediately

retract it because I can think of pieces that do indeed have humor in them

and are written to be entertaining. But by and large you know by their

titles whether they’re to be entertaining or not. But if you write

a serious piece of music, it’s not to be entertaining. It’s to say

this is something I have to say about the human condition. Now that

may be entertaining, but I want you to listen to it with your whole heart

and soul and mind. If you don’t like it, fine, but give it a chance

and maybe it will say something to you. If it does, we’ve connected.

I don’t think that’s entertainment.

BD:

I hope we’ve gotten beyond this now, but is it still more difficult being

a woman composer than just being a composer at the end of the twentieth century?

MJZ: Yes, it’s

still harder than being just a composer, but it’s certainly better, believe

me. The young women composers coming up probably will have problems,

but they’ll have problems because they’re young composers, and the issue

of quality would not be about being women. But it’s still there a little

bit, but for anybody to try and hide behind it is foolish. There is

some prejudice, but the issue today is to be sure you get on the proper network.

It really is networking for males and females, and if you get on, that’s

fine. There are not an enormous number of women composers out there,

but the quality will arise and be recognized. I can’t really believe

that there are really superb women composers who will not ultimately be recognized

anymore. It is true, and the statistics still bear this out, that the

prizes and awards from the NEA and so forth tend to be less in terms of percentage

to women than men. But it may be that’s the way the ball bounces and

that they deserve it. It was pretty bad years ago, but I don’t think

it is now. They used to say to you if you wrote strong music you write

like a man. They don’t say that anymore.

BD: Now they just

say you write strong music?

MJZ: Yes, which

is, of course, the way it should be. Further, and I’ve heard people

argue this point, but my view is that if you don’t know who wrote it, you

do not know whether it was a male or female. The issue is always quality,

and it has nothing to do with male or female.

BD: So it really

does become a superfluous point?

MJZ: I would say

at this point it’s rapidly becoming that, if it isn’t there now, and I’m

very happy to say that. There are some vestiges of it, but not enough

to worry about.

BD: Great!

MJZ: Yes, it is

good, it really is good, and I’m thrilled. I do believe that the young

composers coming up will not have to face that.

BD: They’ll just

have to face the ordinary questions of being performed.

MJZ: Exactly!

That’s hard enough! [Much laughter]

* *

* * *

BD: Let’s talk

a little bit about your friend, Carl Ruggles. What kind of a guy was

he?

MJZ: In some ways he was a very charming man,

and in some ways a very difficult man. He was a very stubborn, irascible

guy.

MJZ: In some ways he was a very charming man,

and in some ways a very difficult man. He was a very stubborn, irascible

guy.

BD: How long did

you know him?

MJZ: He died in

1971, and I knew him from 1964. I spent a year with him in about 1967,

and then went back to visit him about every six weeks until he passed away.

So I knew him very well the last seven or eight years of his life.

Of course he was a very old man when he died. He died at 95, and a

lot of people thought he was senile. That was one of the great tragedies

because he was not senile at all. He was very hard at hearing, and

you had to take the time to make him hear you because he refused to wear

a hearing aid. This was an example of his stubbornness, and so you

simply had to sit there and shout at him to make yourself heard. But

if you did, he was very lucid and quite bright, and not at all senile.

The last years of his life he spent a great deal of time alone, in isolation,

and a nursing home. But he always knew me, and we always had great

conversations when I would come over and talk to him. He was, I think,

a marvelous painter, which he always felt was of less value than his compositions.

He felt much more secure as a painter than he did as a composer, but he was

determined to be known as a composer, and made it!

BD: So he was a

success in the end?

MJZ: Yes.

At least he was recognized, but only partially so.

BD: There are so

many composers who are not that much recognized.

MJZ: That’s true,

but he wanted to be really recognized. He wanted the world to think

that he was the great American composer.

BD: He wanted to

stand along Ives?

MJZ: At least,

if not above! Ives was the only American composer that he really was

willing to admit was his equal, if not his superior. They were very

close friends, and Ives was a wonderful benefactor to him. Ives sent

over money for extra rehearsals when his Sun-Treader was done in Europe.

And after he died, Mrs. Ives gave him the secretary that Charlie had used,

and Carl was very proud of it. They worked in his school house home

for many years. He always said that he and Ives were the two great American

composers, but the world didn’t think that. The world thought that

Ives was, but they weren’t quite sure about Carl. There was always

this doubt.

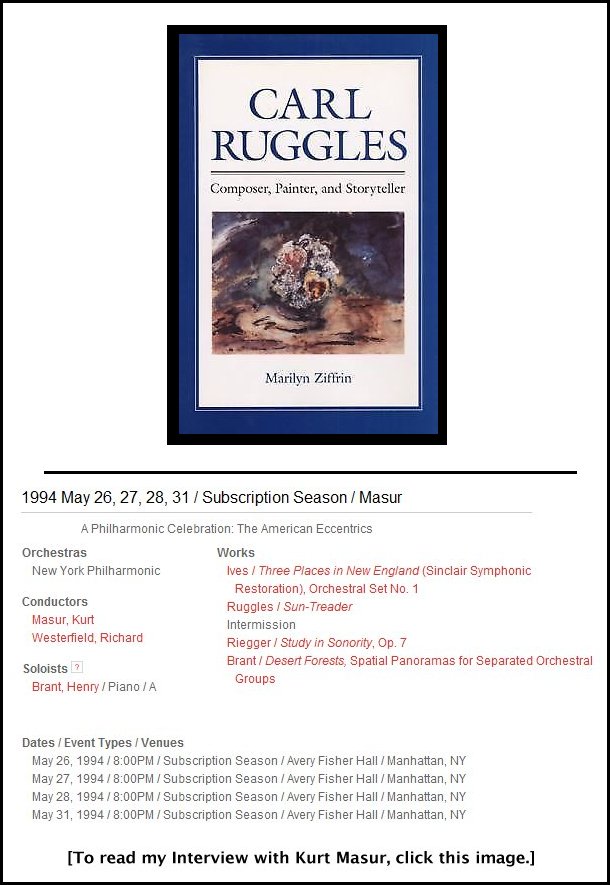

BD: Is the world

reassessing Ruggles now?

MJZ: No, I really

don’t think so, I regret to say. He has had some performances lately,

which is very nice. The New York Philharmonic recently did the

Sun-Treader. They did it on

a program with Ives, Wallingford Riegger and Henry Cowell, and they called

them ‘The American Eccentrics’. [See

program shown below.] I’m not sure Carl would have been pleased

about that at all, although he’d have been delighted to be on the same program

with Ives. I since learned that the Cleveland Orchestra is going to

do some of Ruggles, but I don’t think there’s any resurgence that he’s going

to be played a lot all over, suddenly, forever, and all that sort of thing.

On the other hand, I don’t feel that his music is ever

really gone out. It’s just that it would get played rarely, but it

would continually get played rarely. His paintings, on the other hand,

are in major museums. Most are in private collections, but the Detroit

Institute has some and the Brooklyn Museum has some. He had well over

three hundred paintings but he only had ten compositions. That’s

pretty good, you know!

BD: Why didn’t

he want to be known for his paintings?

MJZ: He always

felt that it came too easily to him. He found out that he could make

money at it, which he did, whereas composition was tough. That made

it more valuable because you fought over it, and he’d been trained as a musician.

He’s not here to speak for himself, so you have to understand I’m trying

to put myself into his mind. But he loved Beethoven and Wagner.

He used to say Wagner made them burn, and the music touched him more deeply

than any painting ever could. And because it touched him that way,

he wanted to do that to other people. That was his great goal.

He wanted to write great music. He wanted to make people burn the way

Wagner made him burn, and he would be satisfied with nothing less.

BD: Is it a pity

that he didn’t give more attention to his painting?

MJZ: I think so

because he was a very fine painter. On the other hand, the pieces of

music that he wrote are chiseled out of granite. He worked over them

and worked over them. His whole method was trial and error, and you

really had to pull his music away from him because he would never let go

of the pieces. He wrote Angels

back in 1922, and in 1966 I was writing a musicological article on that work,

including some of the history and so forth. I was with him at the time

and I was telling about the article, and he still wanted to change some of

the notes! I told him it was ridiculous! It was forty-some-odd

years later, but he still wanted to make some changes. So the pieces

that are extent which, as I say, are ten, are really chiseled out of granite.

BD: Is the music

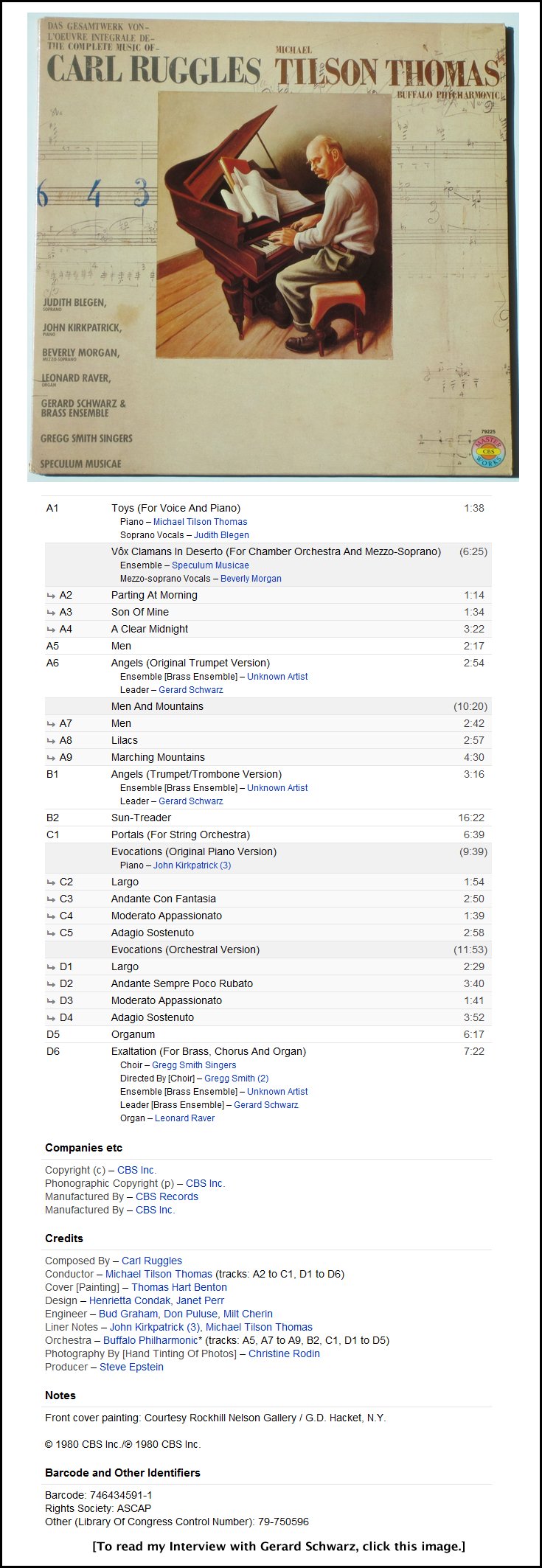

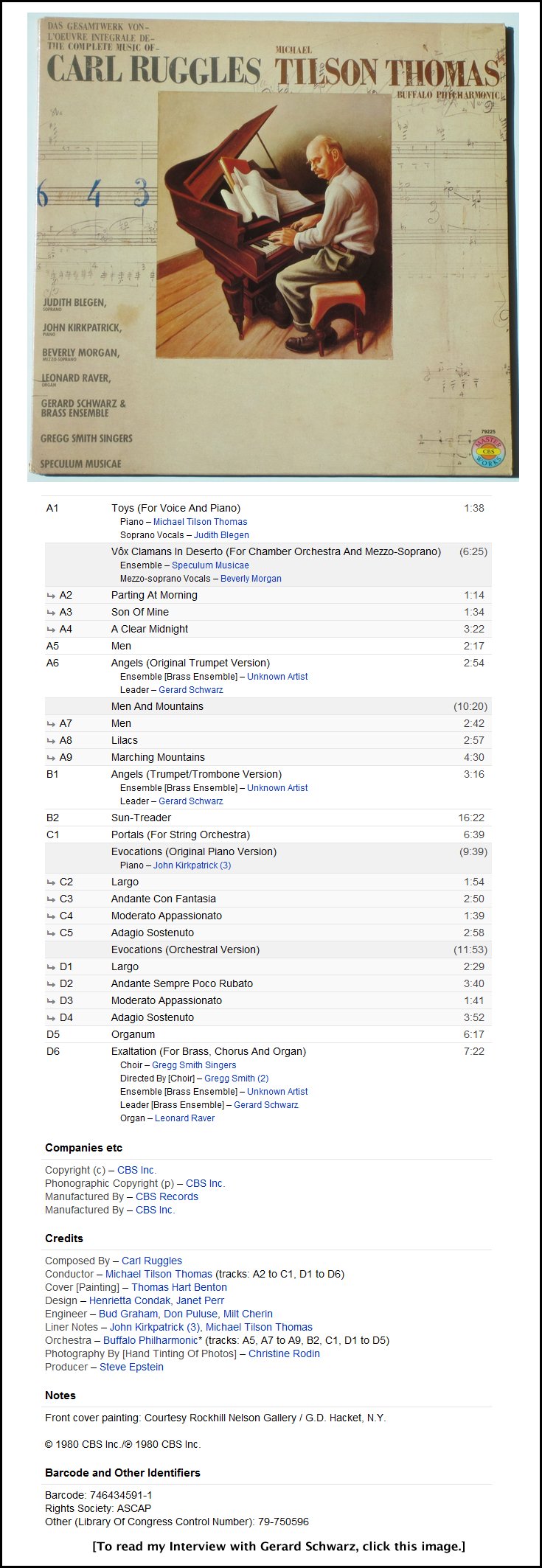

all available? Does the two-record set have everything?

MJZ: Everything

that is available, yes. Having said that, I should say that somewhere

between 1910 and 1920 he decided to destroy all of the pieces that he had

written previous to that. They had been written in the late nineteenth

century parlor song tradition, and he quite literally tore them up.

What he didn’t realize was that there were a couple of songs that had been

published by Gray & Company, and copies were in the Library of Congress.

They are indeed nothing but parlor songs; they’re really not good at all.

So they are the only ones that still exist that are not on those two records.

BD: Does the recording

do his music justice?

MJZ: [Hesitantly]

Yes, I think so. There are two versions of the Evocations on there including the one

that John Kirkpatrick did, and of course he’s the definitive interpreter

of those pieces. The recording that Judith Blegen did of Toys is magnificent. Michael Tilson Thomas has

since recorded the Sun-Treader on

DGG and it’s out on CD. It may be a slightly different version but,

of course, he recorded it on the two record set, too. So yes, I would

say the performances are very good.

BD: Should we treat

the music of Ruggles with kid gloves, or should we throw out there and let

it be heard?

MJZ: Oh, I’d say

throw it out and let it be heard, absolutely! I’d say that for any

music. What do you mean by playing music with kid gloves?

BD: Playing it

with over-reverence.

MJZ: I don’t think

any music should be treated that way. Just throw Carl’s music out and

play it and let the people respond. It’s certainly not that dissonant

anymore. The modern day ear would find it acceptable, if not moving.

There will be some who will say it’s dreadful because it’s so tense and so

tight, but there will be others who’ll wonder why they haven’t heard this

before. It would probably generate some controversy. I don’t mean

people would fight, though I guess they did when the pieces were first performed.

But that’s fine! Carl would like that! The more people

fought about his stuff, the more he liked it.

BD: He would rather

have that than universal accolades?

MJZ: I think probably

so. He loved fights! He would take one side, and if he had the

feeling that you agreed with him, something was wrong, so then he would take

the other side. He was sort of a natural antagonist, and he could take

either side because it didn’t matter to him, just as long as there was some

sort of controversy going on. He loved controversy.

BD: But he wanted

an outcome?

MJZ: Oh, yes, he

wanted you to hear his music. That was important, absolutely important.

Hear the music and then fight about it afterwards, and continue to hear the

music. But you need a fight.

BD: So hear the

music, then fight, then hear it again!

MJZ: Exactly, exactly!

BD: I’ll wear my

boxing gloves next time when I have Ruggles on the turntable!

MJZ: Oh, you should.

But you should play Ruggles, and not just you, but everybody. It’s

important. There was a survey of music critics in the United States

some years ago, and they picked out the ten most important pieces in the twentieth

century written by American composers. The Sun-Treader was among them, and that’s

no small feat for a guy who only wrote ten pieces. So play his music!

Men and Mountains is a marvelous

work, and the Evocations are great.

The one song is absolutely marvelous, but it’s terribly, terribly difficult.

You have to have a really superb singer to be able to carry it across.

Judith Blegen is the singer on the LP, and I think she does a superb job.

[To read another story about Ruggles, see my Interview with Ray Green.]

* *

* * *

BD: Are you optimistic

about the future of music?

MJZ: An honest

answer to that is I rarely think about it. I don’t know. That’s

pretty big. Certainly I’m optimistic that people will never stop writing.

Now whether that means they write in a vacuum and nobody ever plays it, I

don’t know. There will always be this human endeavor, and I suspect

there will always be good music written, I really do. Yes, I guess

I am optimistic.

BD: Are you at

the point in your career that you expected to be at this age?

MJZ: You ask tough

ones! In truth, yes and no. I feel very, very lucky in my life.

Sometimes so lucky that I hope the gods don’t see. But I would like

to be further along. By that I mean I would like to have my music better

known and more often performed, but I think that’s what every composer wants.

BD: Yes, that’s

pretty universal.

MJZ: But in the

long run I feel enormously lucky in my life. Just let me keep on working,

that’s all.

BD: I wish you

lots more productive years!

MJZ: Thank you,

thank you very much. It’s been my pleasure. I’m delighted.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 30, 1994.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB six weeks later, and again in 1996, and on

WNUR in 2007 and 2014. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted

on this website at that time. My thanks to

British soprano Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

BD: I take it that didn’t work out?

BD: I take it that didn’t work out? BD: Do you feel that your own music is part of a

lineage of composers and compositions and styles?

BD: Do you feel that your own music is part of a

lineage of composers and compositions and styles? BD: Is it as scary as having a full sheet of music

paper and you don’t know whether to let it go or still play with it?

BD: Is it as scary as having a full sheet of music

paper and you don’t know whether to let it go or still play with it? MJZ: [Thinks a moment] That’s a biggie!

I could answer you with an equally philosophical statement, “Man

does not live by bread alone!” I really do think

every human being, whether they choose to admit it or not, has an inner life,

and it seems to me that music, serious music, deals with the human inner life,

not the outer life. It won’t make you richer by any means but

it will make you bigger. There’s a wonderful poem by Edna St. Vincent

Millay called The Concert, in which

the woman is talking to her lover and she says, “Do

not go to the concert with me,” because she wants to

go by herself to hear the music and not be distracted by the man she loves.

But she says, “Don’t worry, I’ll come back to you,

but I will come back taller.” I think that’s

the purpose of music. I would even go so far as to suggest it’s probably

the purpose of art, and that ain’t a bad purpose!

MJZ: [Thinks a moment] That’s a biggie!

I could answer you with an equally philosophical statement, “Man

does not live by bread alone!” I really do think

every human being, whether they choose to admit it or not, has an inner life,

and it seems to me that music, serious music, deals with the human inner life,

not the outer life. It won’t make you richer by any means but

it will make you bigger. There’s a wonderful poem by Edna St. Vincent

Millay called The Concert, in which

the woman is talking to her lover and she says, “Do

not go to the concert with me,” because she wants to

go by herself to hear the music and not be distracted by the man she loves.

But she says, “Don’t worry, I’ll come back to you,

but I will come back taller.” I think that’s

the purpose of music. I would even go so far as to suggest it’s probably

the purpose of art, and that ain’t a bad purpose!  BD: This brings up a balance point. How much

is artistic achievement and how much is entertainment value either in music

in general or in your music?

BD: This brings up a balance point. How much

is artistic achievement and how much is entertainment value either in music

in general or in your music? MJZ: In some ways he was a very charming man,

and in some ways a very difficult man. He was a very stubborn, irascible

guy.

MJZ: In some ways he was a very charming man,

and in some ways a very difficult man. He was a very stubborn, irascible

guy.