|

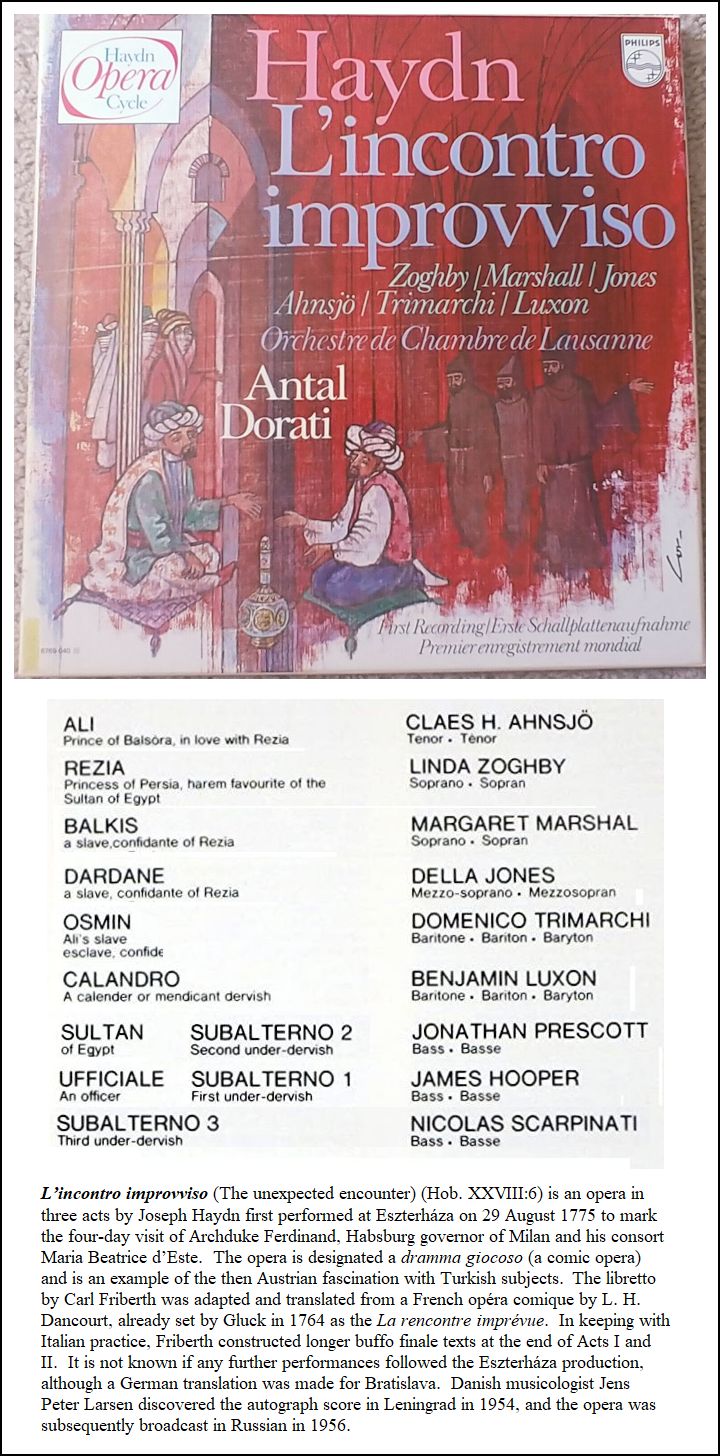

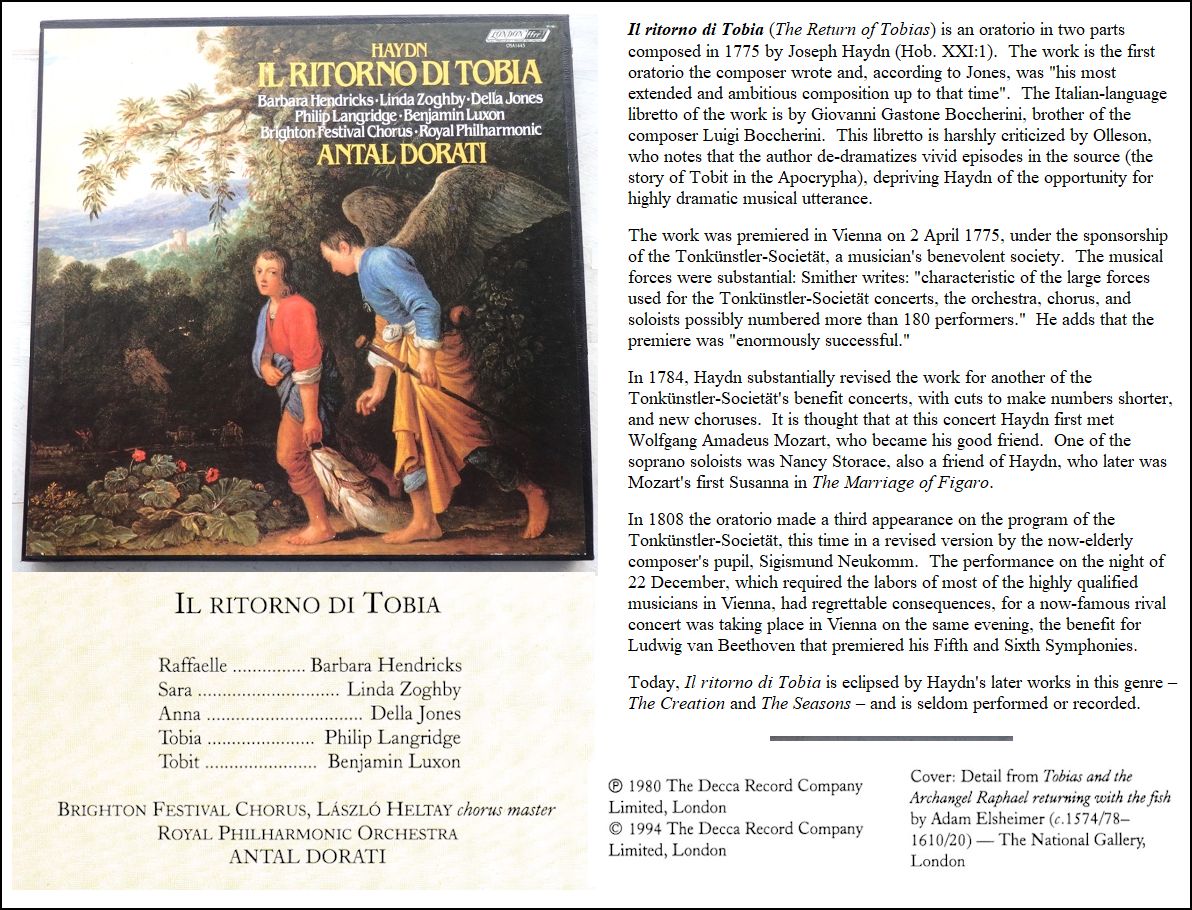

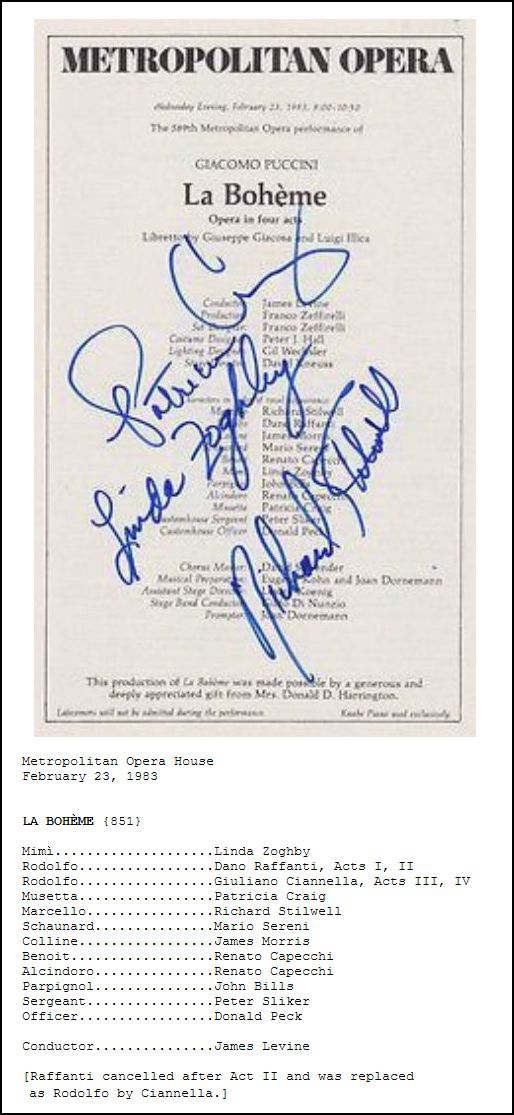

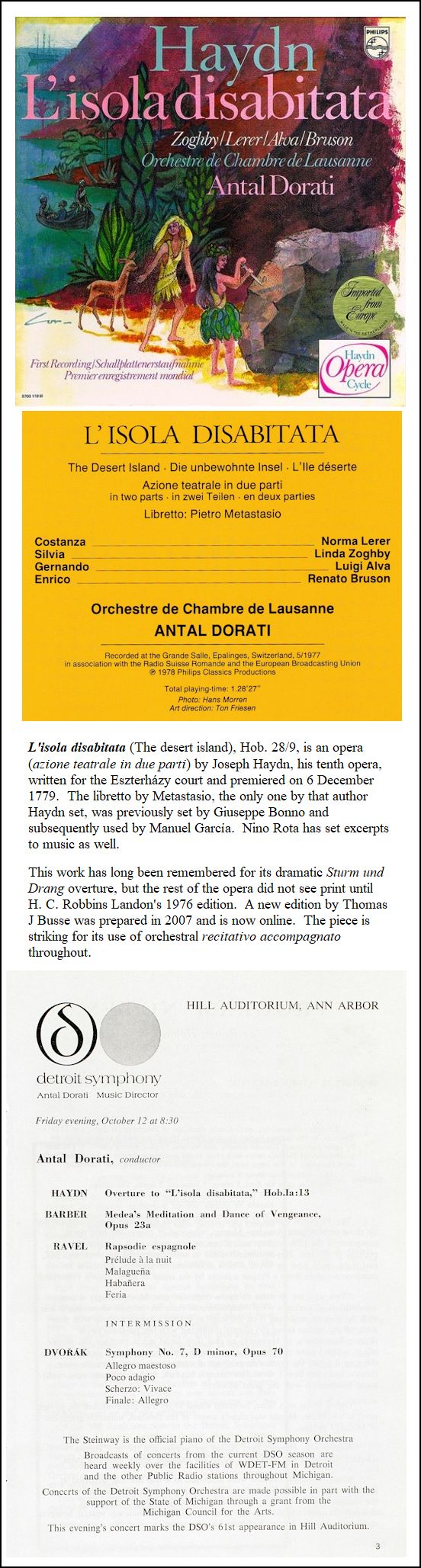

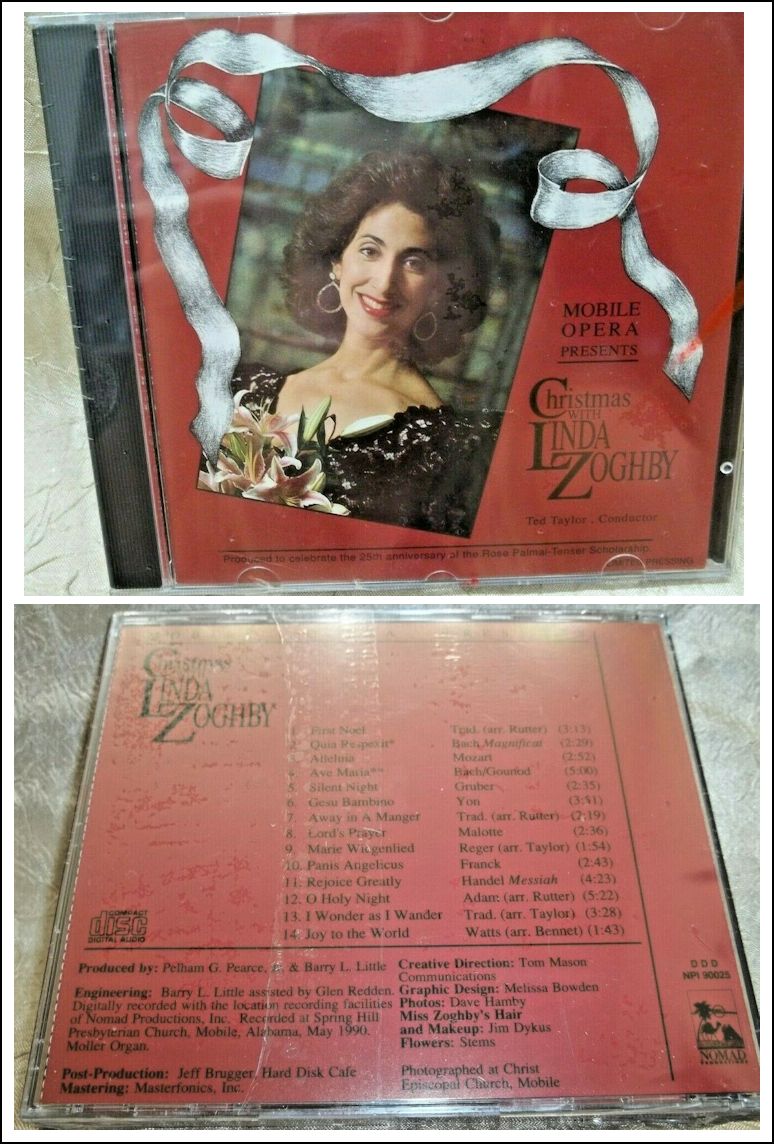

Linda Zoghby was born in Mobile, Alabama (August 17, 1949), and began her vocal studies under Elena Nikolaidi at Florida State University. Her professional debut came in 1973 at Chicago's Grant Park Music Festival, following which she made her stage debut at Houston Grand Opera as Donna Elvira in 1975. Thereafter she sang opera in venues around the United States, including New York City; Washington, D.C.; Dallas; Santa Fe; and New Orleans. On January 19, 1982, she made her Metropolitan Opera debut in La bohème by stepping in at the last minute for Teresa Stratas as Mimì, a performance which won her many critical plaudits. Internationally, Zoghby appeared at the Glyndebourne Festival as Mimì, and as Aminta in La fedeltà premiata by Joseph Haydn. Other roles for which she was known include Pamina, and Marguerite in Faust. During her career she also appeared in performance at the White House, and recorded a number of operas by Haydn. Zoghby is married with three children. A resident of Mobile, she teaches voice at the University of South Alabama. |

Zoghby: Yes, through a stone Neptune appearing,

and lights flashing in all different colors, and lightning being created,

and choruses of seventy or eighty.

Zoghby: Yes, through a stone Neptune appearing,

and lights flashing in all different colors, and lightning being created,

and choruses of seventy or eighty. BD: [Encouragingly] Your mind

works in a musical way!

BD: [Encouragingly] Your mind

works in a musical way! Zoghby: There’s a satisfaction, a purity

of presentation. It’s in your control. Lots of times there

are frustrating aspects to opera. You didn’t choose your costume.

You didn’t choose your cast or conductor in some cases. You might

have directed something differently, or played something differently

than the director might insist that you do. In a recital, you

assemble the elements, and the rate of return can be greater. It

can certainly be great in opera, and almost always I’ve had very satisfying

experiences... with some exceptions. I’ve always found recitals

to be musically very satisfying and rewarding. I love to do them,

and I love to do orchestral works. So, I feel very lucky to have

that mix. I wouldn’t want to do just one.

Zoghby: There’s a satisfaction, a purity

of presentation. It’s in your control. Lots of times there

are frustrating aspects to opera. You didn’t choose your costume.

You didn’t choose your cast or conductor in some cases. You might

have directed something differently, or played something differently

than the director might insist that you do. In a recital, you

assemble the elements, and the rate of return can be greater. It

can certainly be great in opera, and almost always I’ve had very satisfying

experiences... with some exceptions. I’ve always found recitals

to be musically very satisfying and rewarding. I love to do them,

and I love to do orchestral works. So, I feel very lucky to have

that mix. I wouldn’t want to do just one.|

The monodrama takes place in Salisbury Tower, where Eleanor has been a prisoner for nearly sixteen years. Henry II had her confined there after she and her sons led an unsuccessful rebellion against him in France. Overcome by feelings of despair, abandonment and betrayal, she considers taking her life with poison, but instead resolves to distract herself by recalling happier times. As she relives her positive memories of becoming the Queen of France, the memory of her son Richard's death resurfaces. She also recalls the many conflicts she endured with her two husbands, and again finds herself sinking into hopelessness. Time and again her feelings about Richard's death force her into the present, until she finally allows herself release from the guilt and self-doubt surrounding this tragic event. Eventually, she is able to re-assume her role as Queen when the tolling of the bells announces the death of Henry and her liberation from the Salisbury Tower. |

Zoghby: Some. I haven’t done much opera-in-concert.

There’s a place for it, with some of the lesser-known ones to get a hearing,

and for others to decide whether or not they are interested in staging it,

or what the dramatic merits of it might be. Those are the ones which

would never be heard unless they were done this way, so there’s a validity

to that.

Zoghby: Some. I haven’t done much opera-in-concert.

There’s a place for it, with some of the lesser-known ones to get a hearing,

and for others to decide whether or not they are interested in staging it,

or what the dramatic merits of it might be. Those are the ones which

would never be heard unless they were done this way, so there’s a validity

to that.© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 30, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, and again in 1994. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website early the following year. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.