[This interview originally appeared in the

September 1990 issue of The Opera Journal, a quarterly publication

of the National Opera Association.

For this website presentation, it has been slightly re-edited, and the photos

and links have been added.]

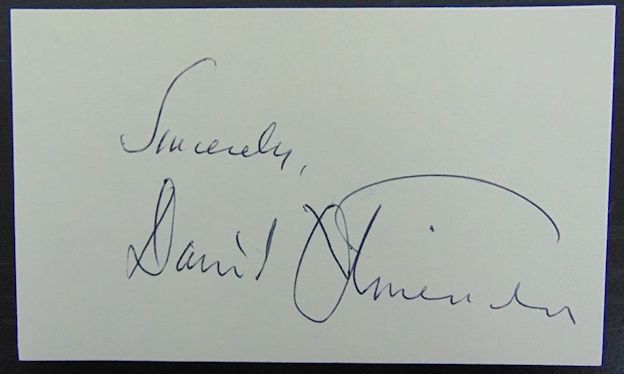

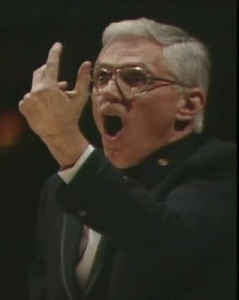

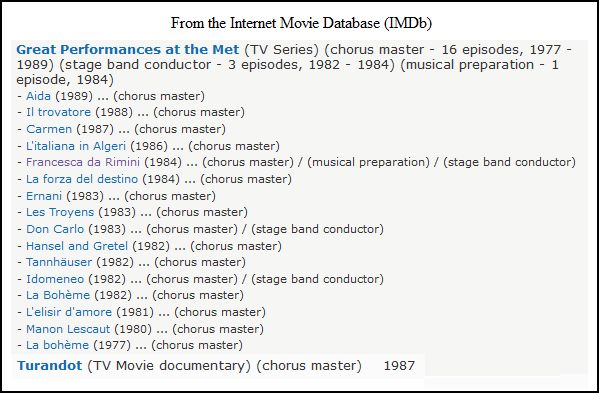

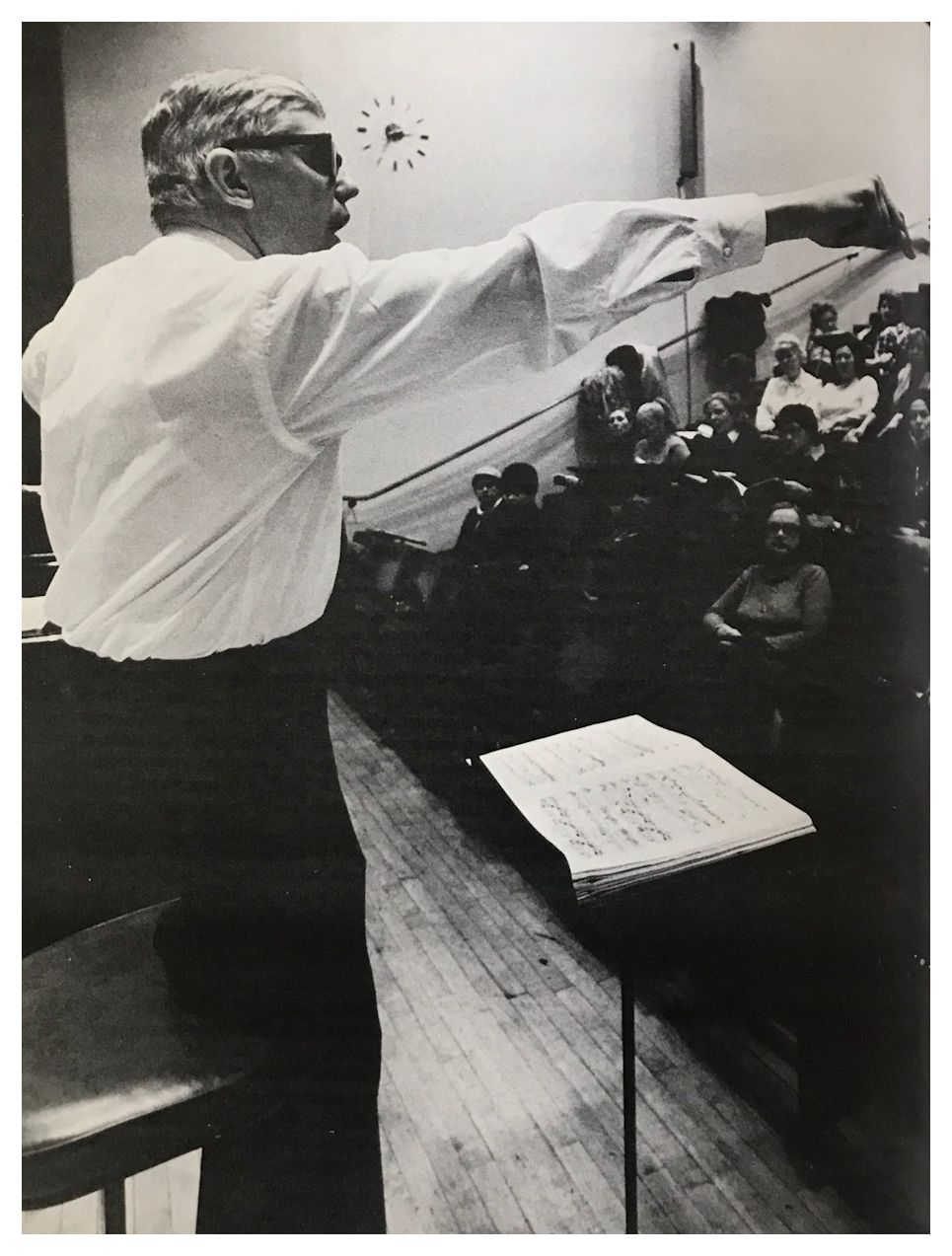

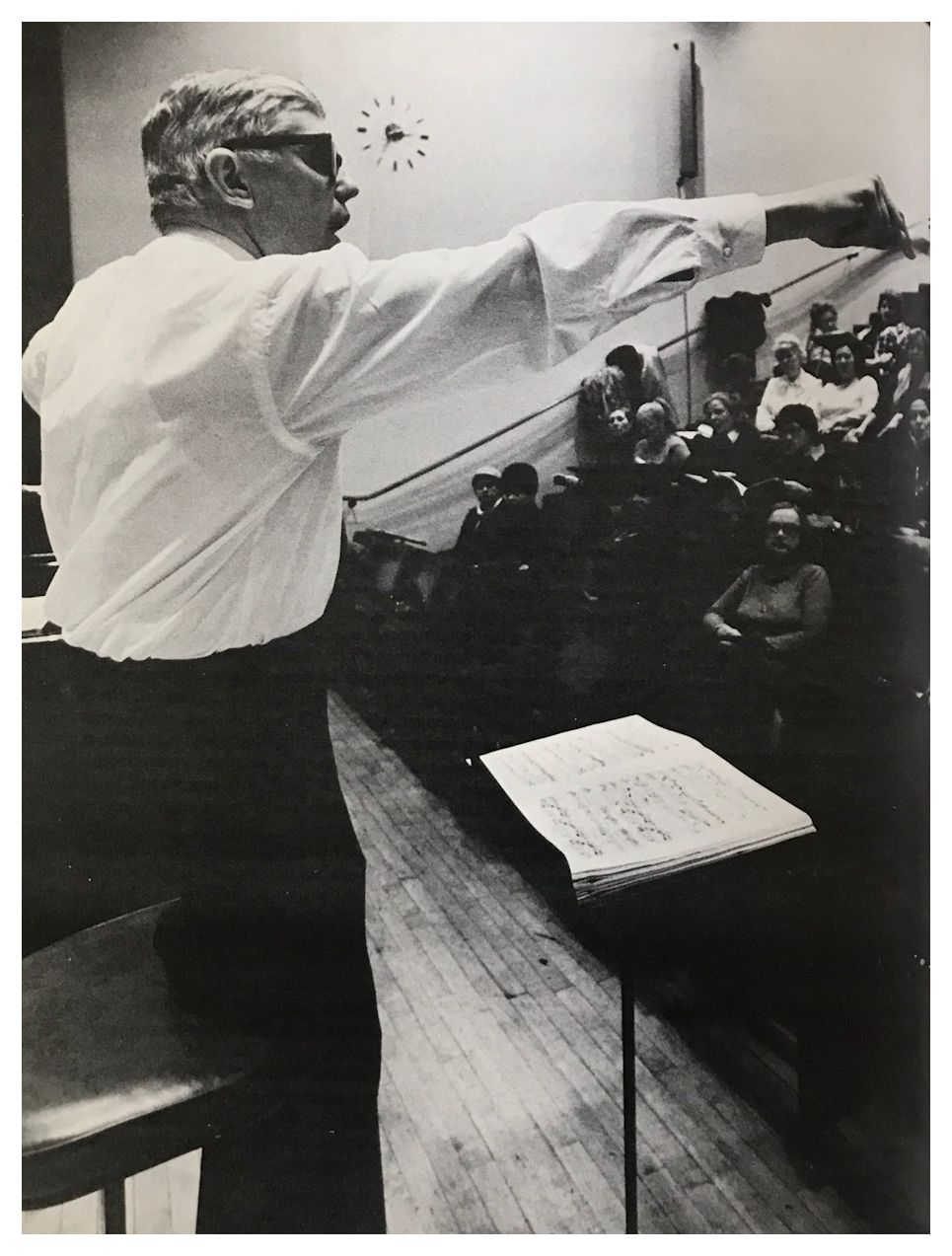

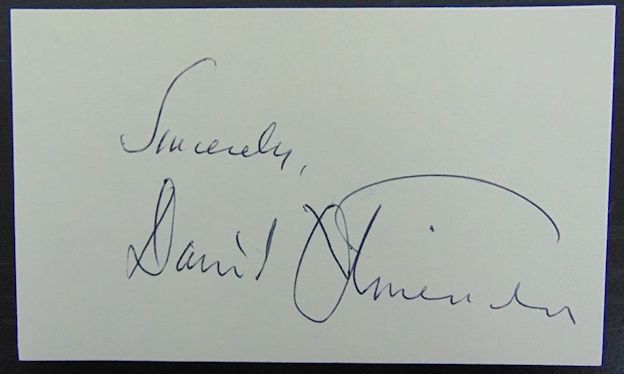

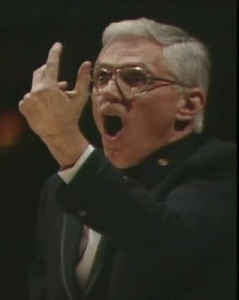

Conversation Piece:

Chorus Master David Stivender

By Bruce Duffie

While operas usually glorify death, in real life we try not to do that

too often. Last time in these pages [June, 1990], we paid tribute

to a career cut short [composer Lee Goldstein].

This issue says, “Thank

you” to a man who spent over thirty years raising

the standards of choral singing in opera, and died in harness this past

February.

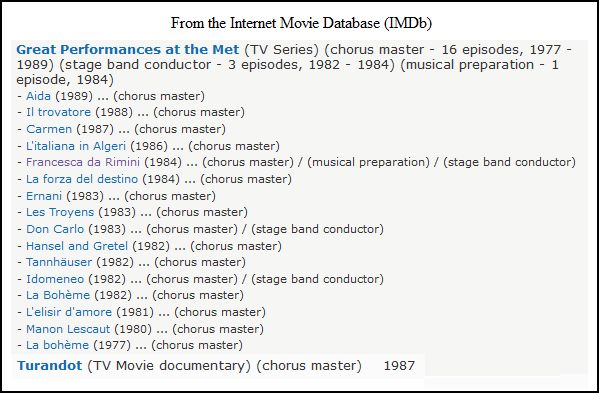

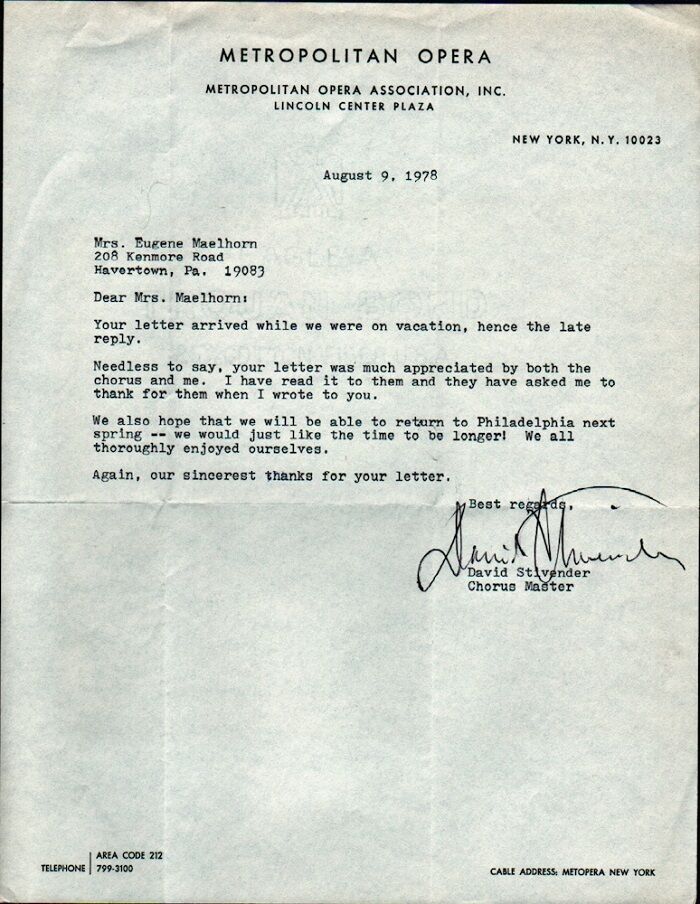

David Stivender was born in Milwaukee in 1933, and after studying at

Northwestern University, he joined the Opera Arts Workshop in Atlanta.

In 1960, he returned to Chicago as assistant to the Chorus Master at Lyric

Opera. He played the piano for the rehearsals, trained the Extra

Chorus, and credits his senior colleague, Michael Leppore, for a superb

education in the choral art. After five seasons in the Windy City,

Stivender was lured to New York and became assistant to Kurt Adler, the

long-time Chorus Master of the Metropolitan Opera. After Adler’s retirement

in 1973, Stivender took over the position, and also assumed some full-conducting

chores starting in 1978.

In April of 1989, David Stivender returned to his alma mater for some

masterclasses, and to receive some recognition which was certainly due.

During the visit, I had the opportunity to speak to him about many ideas

related to the opera. His words reflected his practiced art, and by

sharing them in this journal, we can hope that what he discovered will continue

to live in performances all over the world.

Here is much of that very insightful discussion . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: Besides the obvious, what else is involved

in training the chorus to sing the right notes for the conductor?

David Stivender: Singing the right notes is the easy

part. It’s getting them in the proper time. I’ve learned to

try not to make something of it if I can help it. We learn just what’s

on the page, because when the conductor comes in, he’s gotten ‘The Word’

directly from Donizetti, or Bizet, or Verdi, and theirs is the only way!

[Both laugh] But it’s always different. Every conductor has his

or her own marks, but when the next one comes in, you just erase the blackboard.

One would like to be somewhat creative, and composers like Donizetti expected

certain things, but you learn after a while to eschew those things.

I do it just the way it is written, and they say it’s boring, and yet to

get people to sing strictly in tempo is something you can work very hard

to achieve. The notes and the words, and all the indicated markings

can be drilled in, taking nothing but time to accomplish... and you don’t

always have enough time. We have only a few rehearsals during the season,

and four weeks before the opening night.

David Stivender: Singing the right notes is the easy

part. It’s getting them in the proper time. I’ve learned to

try not to make something of it if I can help it. We learn just what’s

on the page, because when the conductor comes in, he’s gotten ‘The Word’

directly from Donizetti, or Bizet, or Verdi, and theirs is the only way!

[Both laugh] But it’s always different. Every conductor has his

or her own marks, but when the next one comes in, you just erase the blackboard.

One would like to be somewhat creative, and composers like Donizetti expected

certain things, but you learn after a while to eschew those things.

I do it just the way it is written, and they say it’s boring, and yet to

get people to sing strictly in tempo is something you can work very hard

to achieve. The notes and the words, and all the indicated markings

can be drilled in, taking nothing but time to accomplish... and you don’t

always have enough time. We have only a few rehearsals during the season,

and four weeks before the opening night.

BD: Is there a chance that the chorus is working too

many hours per week, with staging rehearsals, and performances?

Stivender: No. The season 1988-1989 was a fairly

easy one, with the Ring, which uses only men in the last opera, and

Salome. Also, last season wasn’t too bad, but next year we’ll

be back to more work, with the new Faust, which has a zillion words

in it, and all those funny sounds. I’d rather teach them Russian, which

is strictly nonsense syllables. Every singer has a terrible time

with French, and they just don’t want to do it.

BD: Why do they have so much trouble with it?

Stivender: There are all those alien sounds.

It was once the International Language, and I don’t think it’s particularly

difficult, but I studied it at Northwestern.

BD: Is it your job to get the right pronunciation

and inflection, or do you bring in a French coach?

Stivender: I do it. I won’t have language coaches.

I make sure I know it very well, and I go over it with coaches myself.

One very famous French coach told me that if you put four French coaches

in a room, you’ll get four different interpretations. It’s all a

matter of taste. There aren’t rules for those things.

BD: Does it, perhaps, have to do with the area of

the country, like a southern drawl which we have in America? If so,

do you go with Parisian taste rather than, say, Marseilles?

Stivender: No, it’s all in the ear, and if you used

Parisian taste, there’d be all those guttural Rs. That’s very bad,

and you shouldn’t sing those. Even French singers don’t use it because

it’s bad style. Only a foreigner would do it. When you go to

Italy, and hear all those dialects, what good is a dialect to a foreigner?

If you live there, or marry a person from that region, and stay there for

the rest of your life, fine. A singer who studies in Rome doesn’t

come away with the dialect you hear in Fellini films. It’s enough

to learn nice, classic Italian. The other is merely an affectation.

BD: Is it hard to learn nice classic English?

Stivender: [Laughs] What is classic English?

We don’t use it! Thomas Allen, who’s from England, has sung Billy Budd

at the Met, and his pronunciation doesn’t jar with ours. Because he’s

such a superb musician, he probably adjusts his words automatically.

I’ve not thought about it until this moment, but it’s never been jarring.

* * *

* *

BD: How did you get involved in opera?

Stivender: I was an unhappy child, and didn’t even

start taking piano lessons until I was twelve years old. They announced

free piano lessons for fifteen minutes a week in Milwaukee, where I grew

up, and my parents rented a piano for me. Finally, I’d found where

I belonged. I loathed physical education classes because I was always

picked last, and found myself way out in the farthest place away from the

game. Nobody told me what to do, and everybody else had been playing

the games for years. Everybody knew, but I didn’t, and I felt like

a pariah. But music wasn’t an escape. Rather, it was an alternative

way of life that was much more interesting. The Milwaukee public library

was sensational in terms of music, so I’d spend my Saturdays there, and I

discovered opera. I’d loved plays, but these operas were sung! They

were not just three-dimensional, but four-dimensional. After this

discovery, I’d go to a play and wonder why they weren’t singing! It

was the same for the ballet — why was

there no singing??? I’d miss it. Even now I miss it! To

me, opera is the ideal expression, and anything else is not very satisfying.

BD: So opera for you is communication?

BD: So opera for you is communication?

Stivender: I suppose... It’s communication amongst

people who know what you’re talking about. I suppose it’s a secret

language. When someone denigrates a Callas or a Scotto for vocal shortcomings,

I’ll point to the volcano of sound, and the spectrum of colors, and array

of shapes and character.

BD: You can take almost any performer and look for

the positive?

Stivender: [Laughs] Of course! What else

is there? It’s easy to hear the squawky high note, but you’ve got to

know what they’re bringing to it. Everybody brings something, or they

wouldn’t be there. If somebody brings you a piece of gossip, like,

“Everybody says she’s terrible,” ask that person who said it. They

won’t be able to nail it down and tell you. It’s always a vague kind

of thing. I don’t know everybody, and I do know you, so who did you

hear it from, and where did that person get it? Track it down!

But to look for the positive aspects of anything pre-supposes a certain knowledge.

BD: Then what should the audiences that come to the

opera know to look and listen for?

Stivender: The more you know about anything, the more

you get into it, and the more you get into it, the more pleasure you get

from it. If you just want to be knocked over by something, go to a

rock concert. We’re raising a generation of deaf kids. You know

how much noise a subway makes, well, I see the kids get on with their earphones,

and I’m at the other end of the car and can still hear their music pounding

away. How loud must that be??? I don’t mean to sound like an

old curmudgeon, but I don’t know that the answer is. [Returning to

the main topic] You must know something about the concerts you’re attending.

I know nothing about rock music, but if I was going to one, I’d find out

about it... and I would have someone convince me why this was something I

should spend time doing! [Both laugh]

BD: OK, then, why should people go to opera?

Stivender: It’s a way of life... at least it has been

for me, and it is for many people, whether they’re in the business of it

or not. It presupposes a certain curiosity. I admit you’re asking

a lot of a tired businessman who works from 8 AM to 6 PM, and then has to

get to the opera after that long day. Where does he have the time to

learn it? Also, is an opera something you get the same enjoyment out

of as you would a Bette Midler concert?

BD: Should opera be for everyone?

Stivender: Everything is for everyone, but you have

to bring something to it. It’s an instinctive thing.

* * *

* *

BD: When preparing the chorus, is it easier to do

an opera they haven’t done in a while, so there are no bad habits to erase?

Stivender: [Laughs] Of course! I’d rather

teach a new anything than restudy Il Trovatore! That opera is

a nightmare for the men. The women are only in one scene, but for the

men the words never stop. The hardest opera of all is La Sonnambula.

That’s the nightmare. Lohengrin is long, and there’s

more for the men of the chorus to sing than for the title character himself.

But to do an opera in any season, you just try to learn it as cleanly as possible.

Each year we try to get it a little cleaner. Open vowels should be

EH, and closed should be EE, and so on. When I work with the chorus

to train them, we spend time and speak the words to get clean diction.

Even in a work that we know, we just go back and get rid of the excesses

that creep in, because little things do creep in. Sets that have steps

are difficult because you can’t go up steps while you are singing.

So your action is spread out on levels, but it’s horizontal rather than up

and down. That puts the choristers far away from one another.

BD: Is that a mistake on the part of the designer?

BD: Is that a mistake on the part of the designer?

Stivender: You have to deal with it the way it is.

I’m not saying it’s good or bad.

BD: I assume you have no choice in repertoire.

Stivender: None whatsoever. I have to take what

I’m given, and I have to take the schedule. You don’t allow yourself

to regret the decisions of the managers and directors. I like some

operas better than others, but there is always pleasure in bringing order

out of confusion. I try to keep that thought in everything I do...

even filling out my taxes! [Laughs] [This conversation was

recorded on April 15, 1989, hence the tax reference!]

BD: Should the voices in your chorus be trained as

soloists, or trained as choristers, and what kind of voices do you look for?

Stivender: Everybody in the Met chorus wanted and sought

a solo career, but I will not take any soloists in the chorus. I want

all those frustrations out before they appear on the Met stage. They

come and learn the work habits. The regular chorus sings twenty-two

operas a year, but they make a very good salary. They don’t need to

take other jobs, and there is no time for anything else. Some try to

keep a church job, but invariably they leave it within a year. If

a singer of a small role comes out, and a chorister feels he or she can do

it better than that soloist, I don’t want them in the chorus. That’s

negative energy, and you get nothing out of that. I know I sound business-like,

but it’s necessary.

BD: [Re-assuringly] You have to be business-like

in order to get the foundation firmly set, so that artistry can be put upon

that foundation.

Stivender: Exactly. I once said that I look for

‘bland’ voices, and couple of the choristers took offense at that.

But what I mean is I want a voice that will blend with others. The

great solo voices are those that are unique. They have a color that

is all theirs. In the greatest ones, it changes and takes on shapes.

There is a different energy for Lady Macbeth than there is for Mimì.

A chorister needs an operatic sound with high notes from the chest, but still

has the intelligence to listen to those around him or her. For my

money, chorus work is much more difficult than solo work. Soloists

can be cavalier about entrances and cut-offs, but if a chorister holds over,

you notice it, and if the entire chorus comes in late, it’s ruined.

BD: Different operas require different numbers of

choristers. Are you the one who decides how many will be on the stage

at any one time?

Stivender: I usually work it with the director.

For instance, in Don Giovanni we have twelve men and twelve women

for peasants — if some of the men can

also be lackeys. There’s enough time to change costumes, but some directors

don’t want the same people to be peasants and lackeys, so then I need eight

more. I don’t feel that anyone notices faces in the chorus, but some

directors just want different ones. The press never mentions the chorus...

BD: Should they?

Stivender: I lived in Italy and there they are mentioned,

good or bad. Even my friends who know I’m the Chorus Master will tell

me they liked Soprano X or Baritone Y, and never mention the chorus.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] But if the chorus

messes up, the critics will be quick to say how bad they were.

Stivender: I’ve found that if the chorus is bad, they

mention it. If it’s OK — just the

status quo — they don’t. We’re like

a file... you keep filing it down, and working away, and getting it better

and better. One critic said that Aïda comes around with

‘mind-numbing regularity’. We do twenty performances

a season, and don’t feel it’s mind-numbing at all.

BD: How do you make sure that the fifteenth and the

seventeenth performance is as fresh and sparkling as the first couple?

Stivender: Musicals run eight performances each week

for years. Twenty Aïdas in a season isn’t so bad when you

think of it that way. You just keep at it. There are certain nights,

however... For instance, Thanksgiving night is tough, because everyone

has had a big meal. So, those nights are very professional.

BD: More professional than artistic?

Stivender: I like to think there is no difference.

That’s what we’re striving for. It would be foolish to say that every

Met performance is absolutely perfect. In Billy Budd, Britten

conceived the ship from the side so all the exits were easy. The chorus

could go down the length of the ship looking out at the conductor. Our

production shows it from the front and it’s dazzling because the decks go

up. But the chorus has to deal with the narrowness, and the men are

several-deep, so the ones in the back can’t see anything. Some get

off too soon, and some don’t see, and you only hear the ones in the front,

so the blend goes. We usually get it right, but occasionally it’s not

exact, so you just have to keep filing away.

* * *

* *

BD: You prepare the chorus in rehearsals. Do

you find yourself on stage giving cues, or doing other tasks?

Stivender: I have an assistant who spells me in performance,

just as choristers don’t do all seven shows per week. By contract

they only do four per week, and everything else is more money. We

try to get it to four, but sometimes it’s six.

BD: Are there no shows when all the chorus

is on stage?

BD: Are there no shows when all the chorus

is on stage?

Stivender: Oh, yes! This is why some seasons,

like last year and the previous, were easier because there were some operas

without chorus — like the Ring,

and Salome. But we try to work out the logistics so that the

smaller choruses don’t overlap. Those few in Don Giovanni usually

are not also in Lucia. Butterfly and Figaro are

small operas for the chorus, and after a few seasons, everyone has done them,

so that helps in setting up the nights off. Next year, though,

has big chorus operas night after night. The women usually have far

less work than the men, but Suor Angelica uses them all.

BD: If someone comes up to you and says they’d like

to spend their life being a choral singer, what advice do you give?

Stivender: Be healthy, and you mustn’t have any technical

vocal problems. Not all operas are written vocally. The choristers

have no trouble with the Verdi operas, nor the Mascagni works. They

were the fathers of the Italian choruses. They understood voices.

On the other hand, Pagliacci comes around, and the tenors just scream.

It’s a nightmare because it’s so wretchedly written.

BD: A soloist will sing only every third or fourth

day, but a chorister may have to sing four or five days in a row every week.

Stivender: If you can sing well, this should help

you, but you’ve got to sing well. That’s why I look for healthy voices,

biggish, healthy voices. I don’t care if they’re expressive or anything

else. That doesn’t matter. I need intelligence because there’s

a lot to learn. Someone who hasn’t done it before goes nuts learning

Trovatore. When we get a new production, there’s rehearsal time,

but revivals get practically none.

BD: Do you get much turnover in your personnel?

Stivender: This season nobody is leaving. They’re

all family people. They have kids to put through school, and mortgages.

There’s hardly any turnover at all. When we need new members, I

like to take them from the Extra Chorus, but it doesn’t always work that

way. Sometimes, someone from outside will be very special, and I’ll

want that voice. There were open auditions last year. I heard

174 singers for no openings. It’s a courtesy we do for the singers’

union, the American Guild of Musical Artists (AGMA). Of that 174,

there were probably 170 decent voices. Of that 170, about seven

really sang well. I’m not a voice teacher, but I’ve worked with voices

all my life.

BD: Have you ever had to fire people?

Stivender: Yes. The usual reason is vocal deterioration.

That is not my responsibility. They are given a certain amount of

money for voice lessons. The stipend at the beginning of every season

is there to keep your voice up. The shape of the tool you work with

must be your responsibility. It cannot be anyone else’s. If

you come into the chorus and we’re doing Trovatore without much rehearsal,

I will warn you that it’s tough, and you’d better learn it on your own.

I don’t want any excuses. You have to learn it and do it. I’m

not vicious, but I will let you know that you need to get some extra help

with the music. Being Chorus Master can be a very difficult task.

I often feel that I’d rather be a chorister than a leader.

BD: Do you ever get out there and sing a performance

or two?

Stivender: No. Those days are gone. Verdi

said in letters that he expected the Chorus Master to put on a costume and

help them on stage, but those are gone. I used to stand in the wings

and snap my fingers, and help with cues, but I don’t do that anymore.

In the old days, when I was an assistant, the chorus would still carry

books on stage for the first rehearsals. That was the first thing

I got rid of. I will make sure that as a chorus, there is enough rehearsal

time. I will teach it to them. I will learn it first, and then

bat it into them, but they must come to the rehearsals with open minds and

listen. I start on the dot, and we work fifty minutes, then we stop

right on the clock. If you expect me to teach, you have to respond.

I love teaching. I think it’s the neatest thing, but there is

a lot of drill involved. It’s boring work because repetition is tough.

But, as with any teaching, you find ways to make it more attractive.

You make jokes, and find certain mnemonic devices. Cut-offs are tricky,

and conductors, who have gotten ‘the word’ from on high, still often neglect

cut-offs. Sometimes they don’t even look up and give an attack.

I have made it so that the conductors don’t really have to worry about the

chorus.

BD: Could your chorus be at home in a Beethoven Ninth,

or a Missa Solemnis?

Stivender: I would like to think so. The only

thing we’ve done like that is the Mahler Second Symphony, but James Levine, who conducted,

and I realized that Mahler had an operatic chorus in mind. The premiere

was at the Berlin Opera. An operatic chorus sound is different.

They are real voices that are sometimes a little raw. On recordings,

now, we’re used to a sort of glassy thing that’s all the same. I hate

that. I want there to be inflection and life. The Mahler is

not a character text, but it does have its own character. If you have

real voices going, it’s different than a smooth and perfect sound.

I recently heard an opera performance with a symphony-type chorus, and I

thought I’d go crazy. It was a larger number of people, but the character

was always the same. Nothing changed. It’s a way of doing it,

and I’m not saying there is only one way of doing it, or that my way has

to be the best, but it is a matter of opinion. Many people thought

that our performance of the Mahler was perfectly wonderful.

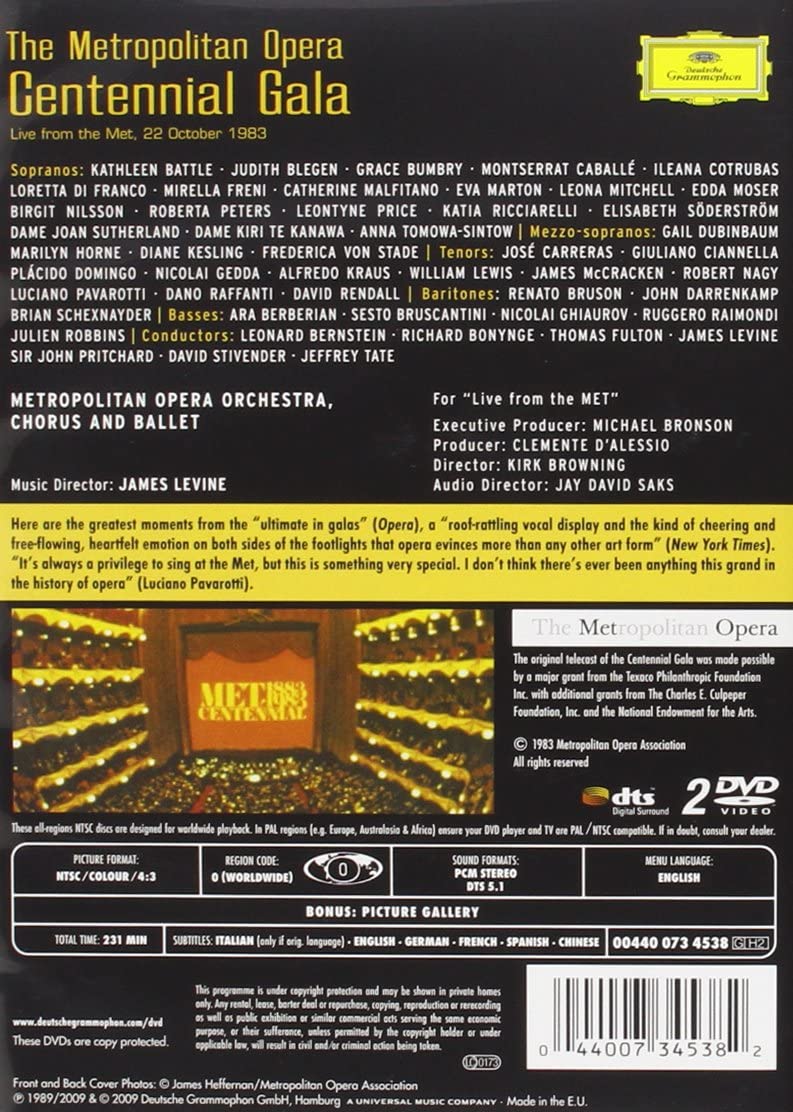

See my interviews with Judith Blegen, Grace Bumbry, Ileana Cotrubas, Mirella Freni, Catherine Malfitano,

Eva Marton, Birgit Nilsson,

See my interviews with Judith Blegen, Grace Bumbry, Ileana Cotrubas, Mirella Freni, Catherine Malfitano,

Eva Marton, Birgit Nilsson,

Roberta Peters, Elisabeth Söderström,

Dame Joan Sutherland,

Dame Kiri te Kanawa, Anna Tomowa-Sintow, Marilyn Horne, Giuliano Ciannella,

Alfredo Kraus, James McCracken, Sesto Bruscantini,

Nicolai Ghiaurov, Ruggero Raimondi, Richard Bonynge,

Sir John Pritchard,

and Jeffrey Tate.

BD: One last question. Is conducting fun?

Stivender: Conducting in the theater is the most difficult

conducting of all. Anything can happen, and that’s why you find a lot

of conductors don’t want to work in the theater. For a symphonic concert,

the audience is looking at you. In the opera, nobody looks at you

except when you walk in and walk off. If you happen to be a big star,

and that means something to your career, fine. In an orchestra concert,

they’re all right there with music looking at you. In the opera, sure,

the orchestra is there with music looking at you, but you’ve also got a bunch

of singers doing it all from memory. They’re three miles away, and

they can forget this and that. Anything can happen, and usually does.

Something happens in every performance, but the audience is most often never

aware of it. Conducting is fun at the end of the performance when you

put the baton down, and only then! Up to then it’s a nightmare for

me. Would the composer have been pleased with what we did? You

work hard and study, and there’s nothing more exciting than precise knowledge

— not general knowledge, but precise knowledge.

Conducting is compromise. Some conductors demand this or that, and

great big stars don’t sing with those conductors. I find that those

hurdles and obstacles make it interesting, and spur me on.

===== =====

===== =====

After contributing to The Opera Journal since 1985, Bruce Duffie

finally had the pleasure of meeting in person the past and present Editors

on their recent trip to Chicago. It was mutually agreed that once

was far more than enough, and a repetition is scheduled immediately following

the formation of glaciers in the back yard of Mephistopheles. (!)

However, despite this amazing turn of events, the next issue will

contain a conversation with director, Frank Corsaro, to celebrate

his sixtieth birthday. The following issue will present Martin Feinstein, the

General Director of the Washington Opera on his seventieth birthday.

== == == == ==

* * *

== == == == ==

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on April 15, 1989, hence

the reference to doing his taxes! The original transcript was made

the following year, and published in The Opera Journal in the September

issue. The transcript was slightly edited in 2020, and posted

on this website at that time. Portions were

also broadcast on WNIB in 1993. My thanks to British soprano

Una Barry for

her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted on this website, click here.

Award -

winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with

WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final

moment as a classical station in February of 2001.

His interviews have also appeared in various magazines

and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast

series on WNUR-FM.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected transcripts

of other interviews, plus a full list of his

guests. He would also like to call your attention

to the photos and information about his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail

with comments, questions and suggestions.

David Stivender: Singing the right notes is the easy

part. It’s getting them in the proper time. I’ve learned to

try not to make something of it if I can help it. We learn just what’s

on the page, because when the conductor comes in, he’s gotten ‘The Word’

directly from Donizetti, or Bizet, or Verdi, and theirs is the only way!

[Both laugh] But it’s always different. Every conductor has his

or her own marks, but when the next one comes in, you just erase the blackboard.

One would like to be somewhat creative, and composers like Donizetti expected

certain things, but you learn after a while to eschew those things.

I do it just the way it is written, and they say it’s boring, and yet to

get people to sing strictly in tempo is something you can work very hard

to achieve. The notes and the words, and all the indicated markings

can be drilled in, taking nothing but time to accomplish... and you don’t

always have enough time. We have only a few rehearsals during the season,

and four weeks before the opening night.

David Stivender: Singing the right notes is the easy

part. It’s getting them in the proper time. I’ve learned to

try not to make something of it if I can help it. We learn just what’s

on the page, because when the conductor comes in, he’s gotten ‘The Word’

directly from Donizetti, or Bizet, or Verdi, and theirs is the only way!

[Both laugh] But it’s always different. Every conductor has his

or her own marks, but when the next one comes in, you just erase the blackboard.

One would like to be somewhat creative, and composers like Donizetti expected

certain things, but you learn after a while to eschew those things.

I do it just the way it is written, and they say it’s boring, and yet to

get people to sing strictly in tempo is something you can work very hard

to achieve. The notes and the words, and all the indicated markings

can be drilled in, taking nothing but time to accomplish... and you don’t

always have enough time. We have only a few rehearsals during the season,

and four weeks before the opening night. BD: So opera for you is communication?

BD: So opera for you is communication? BD: Is that a mistake on the part of the designer?

BD: Is that a mistake on the part of the designer?

BD: Are there no shows when all the chorus

is on stage?

BD: Are there no shows when all the chorus

is on stage?