|

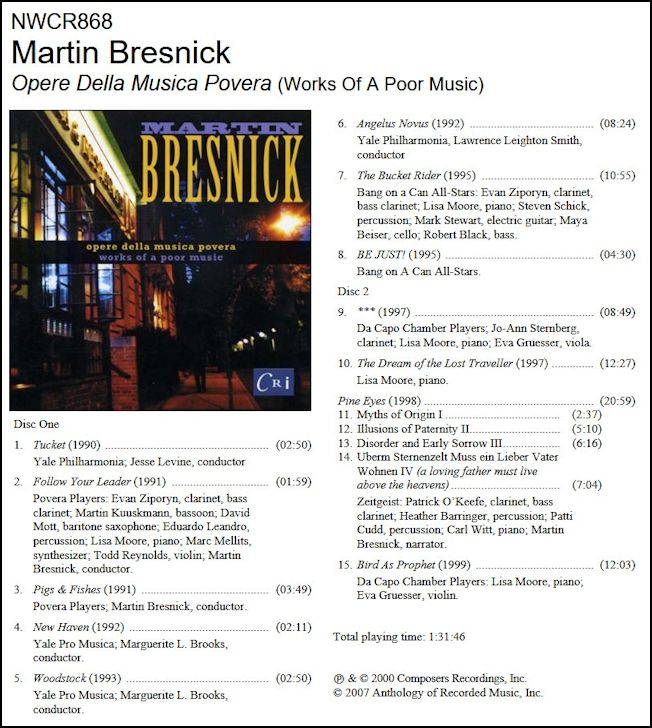

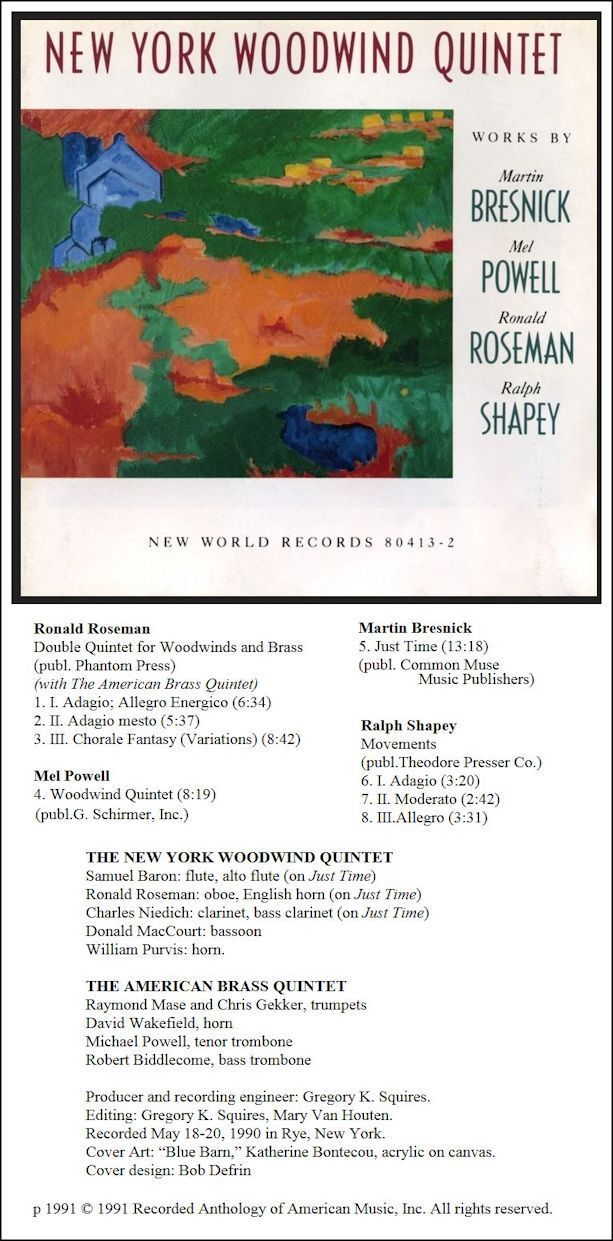

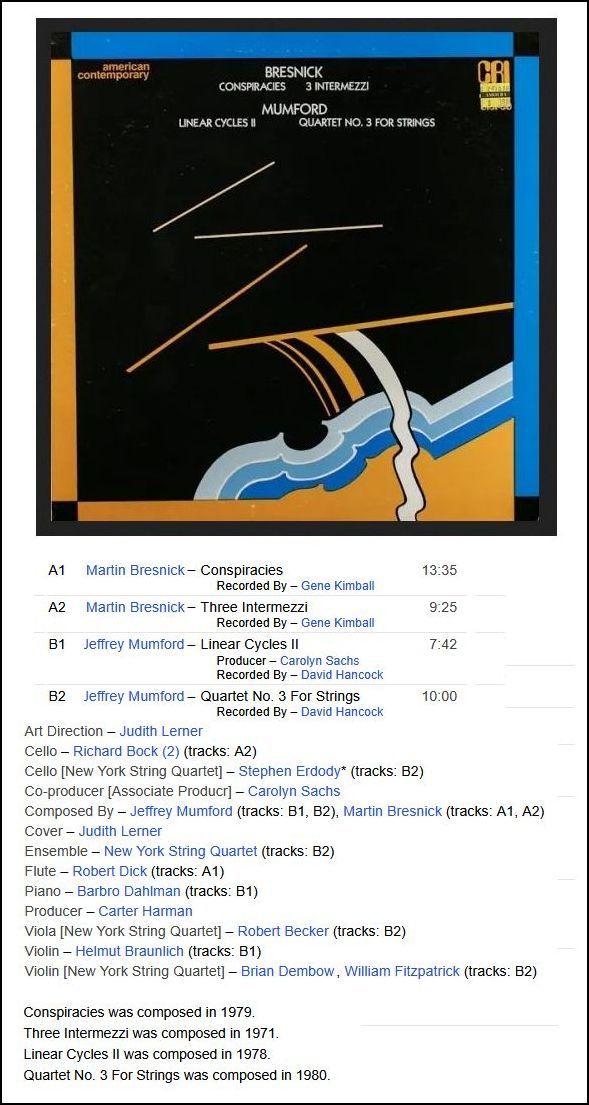

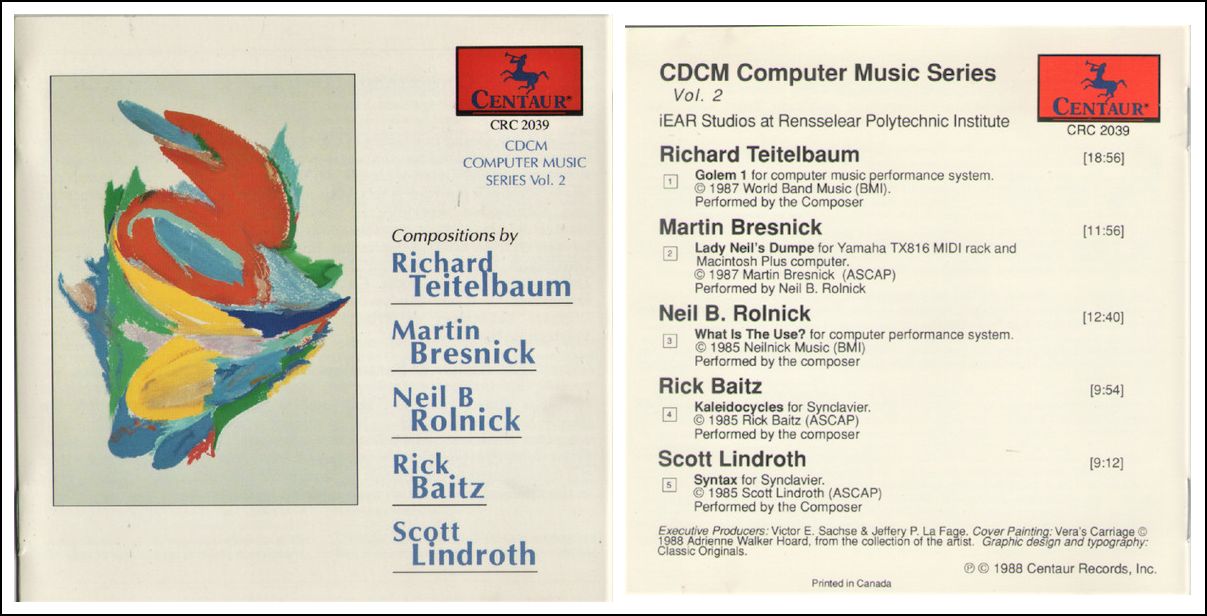

Bresnick (born November 13, 1946) grew up in the Bronx, and is a graduate of New York City's specialized High School of Music and Art. He was educated at the University of Hartford (B.A. '67), Stanford University (M.A. '68, D.M.A. '72), and the Akademie für Musik, Vienna ('69–'70), and studied composition with John Chowning, György Ligeti and Gottfried von Einem. He went on to teach at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Stanford University and the Yale School of Music. Bresnick’s work has received many prizes, among them: Fulbright Fellowship (1969–70), three NEA Composer Grants (1974, 1979, 1990), Rome Prize Fellowship (1975–76), MacDowell Fellowship (1977), First Prize, Premio Ancona (1980), First Prize, International Sinfonia Musicale Competition (1982), Connecticut Commission on the Arts Grant, with Chamber Music America (1983), The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Elise L. Stoeger Prize for Chamber Music (1996), "Charles Ives Living" award, American Academy of Arts & Letters (1998), Composer-in Residence, American Academy In Rome (1999), Berlin Prize Fellow, American Academy in Berlin (2001) a Guggenheim Fellowship (2003), and was elected to membership, American Academy of Arts and Letters (2006). Bresnick is currently a professor at the Yale School of Music, where he has been a widely influential teacher of contemporary composition. His teaching has been recognized by a Walter J. Gores Award for Excellence in Teaching at Stanford University, a Morse Fellowship from Yale University (1980–81), the ASCAP Foundation's Aaron Copland Prize for teaching, and the Yale School of Music’s highest honor, the Sanford Medal for Service to Music. Bresnick has been recognized as having composed a large catalog of respected works while teaching and as an influential voice at the Yale School of Music. Notable recent performances including a 60th birthday retrospective at Carnegie Hall’s Zankel Hall, the premiere of his oratorio “Passions of Bloom” on the International Festival of Arts and Ideas, the premiere of his fourth string quartet “The Planet on the Table” by the Brentano String Quartet, and a performance of his piano concerto “Caprichos Enfaticos” at the Nasher Sculpture Center. As a composer for films, he has contributed many scores for documentary films, including Arthur and Lillie (1975) and The Day After Trinity (1980), both of which were nominated for Academy Awards. He also composed the score for the PBS documentary Muhammad: Legacy of a Prophet. |

© 2003 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in my office in the School of Music at Northwestern University in Evanston, IL, on November 19, 2003. Portions were broadcast on WNUR two months later, and again in 2017. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.