Two Conversations with Bruce Duffie

|

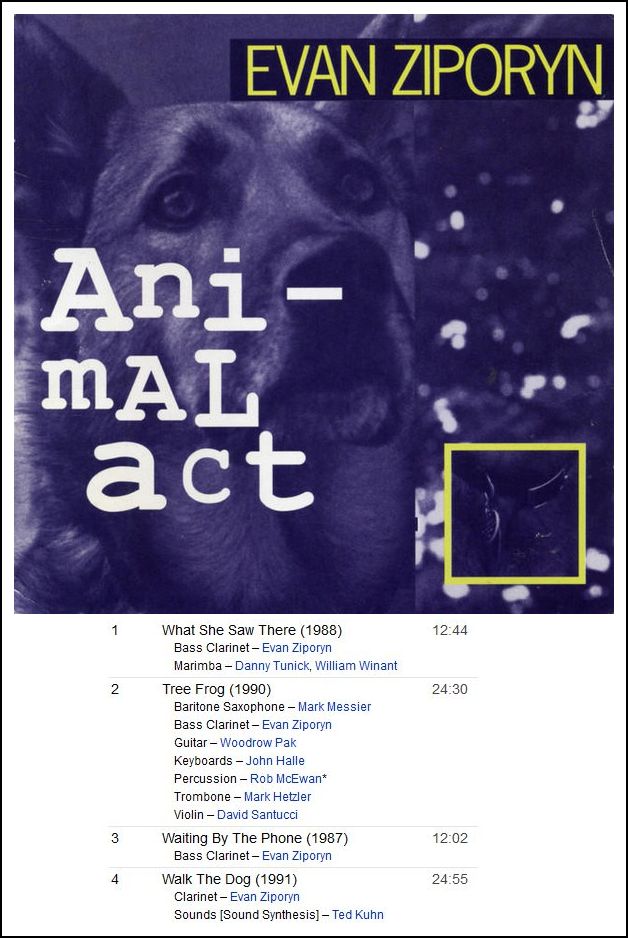

Hailing from Chicago, clarinetist Evan Ziporyn makes music at the

crossroads between genres and cultures, east and west. He studied

at Eastman, Yale & UC Berkeley with Joseph Schwantner,

Martin Bresnick, & Gerard Grisey. He first traveled to Bali in

1981, studying with Madé Lebah, Colin McPhee's 1930s musical

informant. He returned on a Fulbright in 1987. Evan recorded the

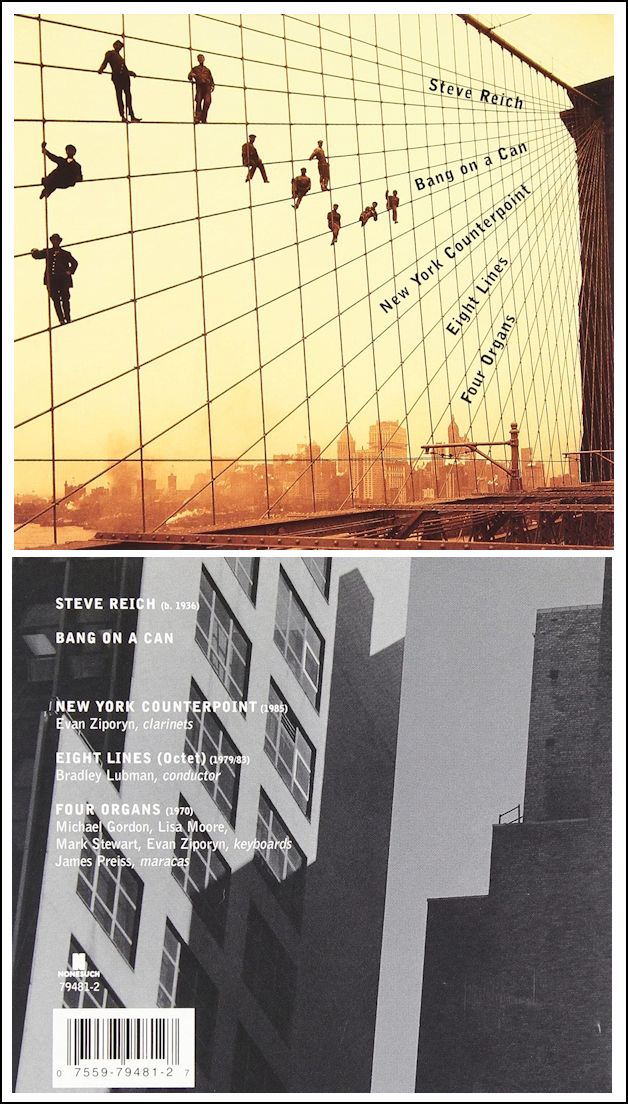

definitive version of Steve Reich's multi-clarinet

NY Counterpoint in 1996, sharing in that ensemble's Grammy in 1998.

Evan is the Kenan Sahin Distinguished Professor of Music at MIT. He

also serves as Head of Music and Theater Arts, and was appointed Inaugural

Director of MIT's new Center for Art Science and Technology. == From the Silk Road website * * * *

*

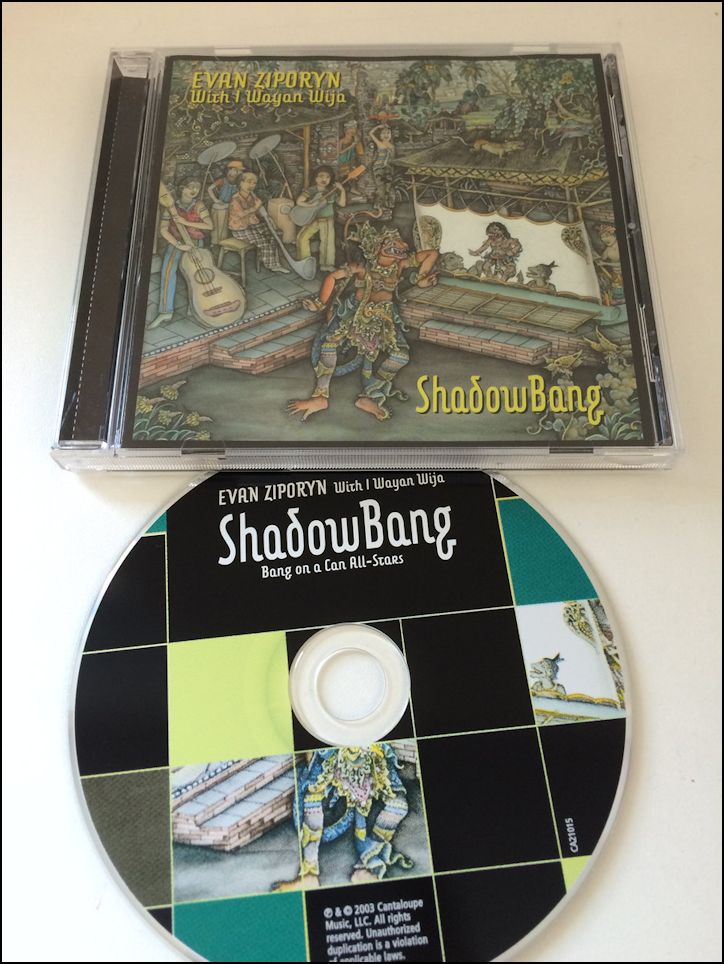

His music has been commissioned and performed by Yo-yo Ma’s Silkroad Ensemble, Brooklyn Rider, Maya Beiser, Roomful of Teeth, Bang on a Can, Kronos Quartet, Wu Man, the American Composers Orchestra, Sentieri Selvaggi, the American Repertory Theater, Steven Schick, So Percussion, Gamelan Sekar Jaya, Sarah Cahill, and the Boston Modern Orchestra Project. They have been presented at international venues including Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall, London’s Barbican Center, the Holland Festival, the Singapore Festival, the Sydney Olympics, and the Bali International Arts Festival. His opera A House in Bali (directed by MIT colleague Jay Scheib) was featured at BAM Next Wave in 2010; that same fall his works were featured at a Carnegie Hall Zankel Making Music composer’s portrait concert. Ziporyn tours and records regularly as a soloist and as a member of Eviyan (with Iva Bittova and Gyan Riley). From 1992-2012 he was a founding member of the Bang on a Can All-stars (Musical America’s 2005 Ensemble of the Air), finishing his tenure with the group with an appearance on an episode of PBS’ Arthur. His long-time work with the Steve Reich Ensemble led to sharing a 1999 Grammy for Best Chamber Performance for their recording of Music for 18 Musicians. He is also the featured multi-tracked soloist on Reich’s Nonesuch recording of New York Counterpoint. Other awards include a 2012 Massachusetts Arts Council Fellowship, the 2007 USArtists Walker Award and the 2004 American Academy of Arts and Letters Goddard Lieberson Fellowship. His puppet opera Shadow Bang, a collaboration with master Balinese dalang Wayan Wija, was premiered at MassMOCA, and was the centerpiece of the 2006 Amsterdam GrachtenFest. Recordings of his works have been released on Sony Classical, Cantaloupe Music, New Albion, New World Records, Koch, Innova, Victo, Animal Music, and CRI. He has collaborated with some of the world’s most creative and vital living musicians, including Brian Eno, Paul Simon, Ornette Coleman, Thurston Moore, Meredith Monk, Bryce Dessner, Philip Glass, Terry Riley, Louis Andriessen, Shara Worden, Sandeep Das, Kelley Deal, Cecil Taylor, Henry Threadgill, Wu Man, Matthew Shipp, Wayan Wija, Kyaw Kyaw Naing, and Ethel. Recent projects include In My Mind & In My Car (w/Christine Southworth), an hour-length work for bass clarinet and electronics, which he has performed at festivals in the US, Canada, Belgium, Poland, and Indonesia; compositions and arrangements for Ken Burns’ upcoming Vietnam documentary, arrangements for Silkroad Ensemble’s most recent CD, Sing Me Home. Recently he released a new Eviyan CD, as well as CDs of collaborations with DuoJalal, Czech composer Beata Hlavenkova, and Polish jazz masters Waclaw Zimpel and Hubert Zempel. Additionally, his performance with the MIT Wind Ensemble of Don Byron’s Clarinet Concerto, commissioned by MIT, and released on Sunnyside Records, received a 5-star Downbeat review. == From the MIT website

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: Have you made a specific study

of Indonesian music?

BD: Have you made a specific study

of Indonesian music? Ziporyn: Those are two separate questions.

With a couple of notable exceptions, by the time a piece gets around

to a performance, I’m usually very happy about it. But that’s

because I insist a lot on often reworking things during rehearsals

when they don’t come out as I expected them to, for various foreseen

or unforeseen reasons. These can range from expediency, to having

performers who can accomplish the technical demands.

Ziporyn: Those are two separate questions.

With a couple of notable exceptions, by the time a piece gets around

to a performance, I’m usually very happy about it. But that’s

because I insist a lot on often reworking things during rehearsals

when they don’t come out as I expected them to, for various foreseen

or unforeseen reasons. These can range from expediency, to having

performers who can accomplish the technical demands. Ziporyn: [Laughs] If they know

where it’s heading, I wish they’d tell me! [Much laughter] Then

we could get there sooner!

Ziporyn: [Laughs] If they know

where it’s heading, I wish they’d tell me! [Much laughter] Then

we could get there sooner! BD: Have most of your pieces been played on new-music

concerts?

BD: Have most of your pieces been played on new-music

concerts? BD: [Looking over some material destined

for use on the radio] Let’s talk a little bit about the orchestral

piece.

BD: [Looking over some material destined

for use on the radio] Let’s talk a little bit about the orchestral

piece. Ziporyn: Oh, just as the sounds.

But they’re not sound. They’re going to be made sounds by the

people who do it.

Ziporyn: Oh, just as the sounds.

But they’re not sound. They’re going to be made sounds by the

people who do it.Five years later, in September of 1994, we met again and had another conversation . . . . .

Ziporyn: Maybe it’s like Heraclitus’s

river, so it’s never the same twice. [Both laugh] There is

music that’s more easily used up than others to begin with, and sometimes

in my own work I am very conscious of making it rich enough to survive

enough feedings by putting enough in it so that, as time goes by, maybe

you hear different things in it. I find this even from my own point

of view. Since I’m doing so much more performing now, I’m really

conscious of making music that’s going to hold my interest as a player

the tenth time around, or the twentieth time around, and not just have

it feel good on a surface or visceral level... although I want it to do

that too.

Ziporyn: Maybe it’s like Heraclitus’s

river, so it’s never the same twice. [Both laugh] There is

music that’s more easily used up than others to begin with, and sometimes

in my own work I am very conscious of making it rich enough to survive

enough feedings by putting enough in it so that, as time goes by, maybe

you hear different things in it. I find this even from my own point

of view. Since I’m doing so much more performing now, I’m really

conscious of making music that’s going to hold my interest as a player

the tenth time around, or the twentieth time around, and not just have

it feel good on a surface or visceral level... although I want it to do

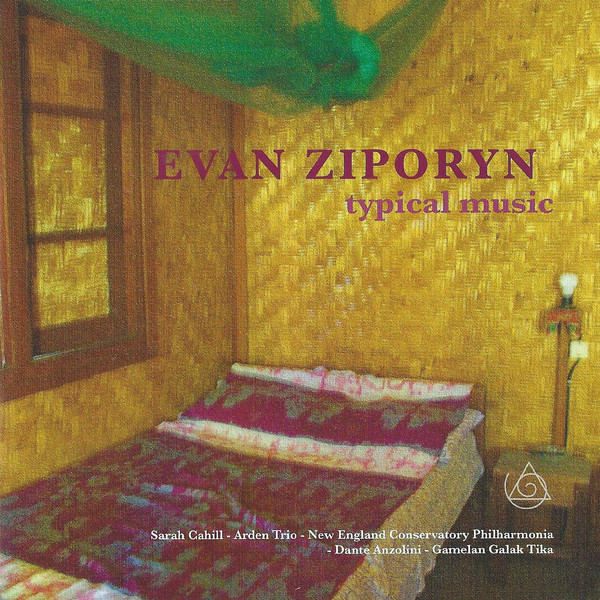

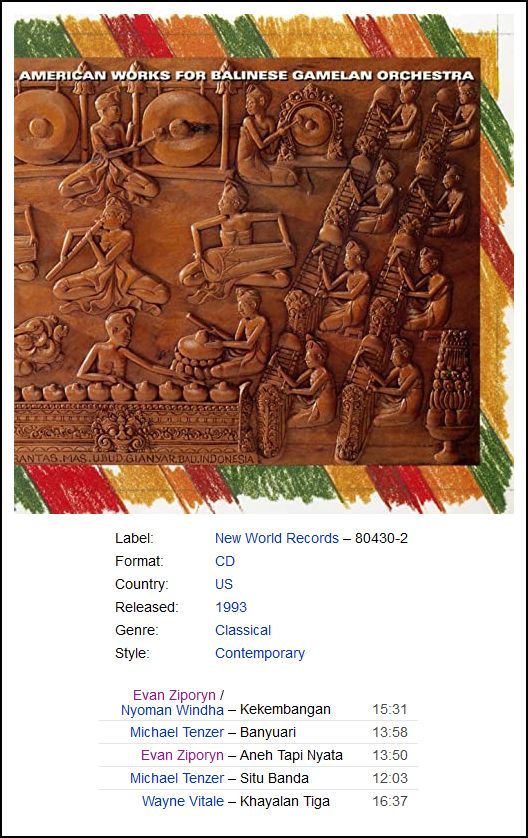

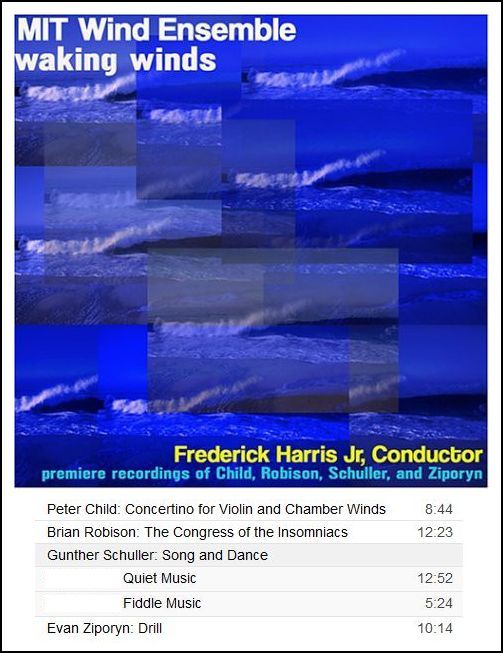

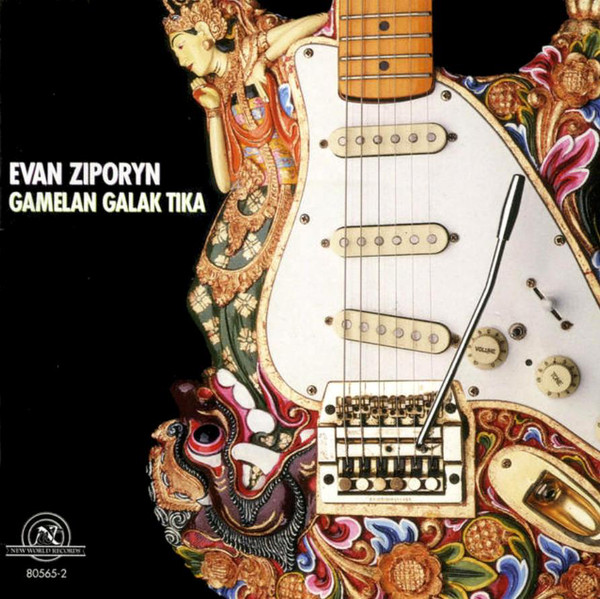

that too. Ziporyn: Oh, absolutely. Since the last

time we really had a conversation, I’ve been involved more and more with

preparing performances for people in far-flung places. I did Aneh

Tapi Nyata, for gamelan and Western instruments [recording shown

at right], that was designed to be played at the Bali Arts Festival

for an audience of Balinese. Now I’m working on a piece for a Dutch

brass orchestra, the Orkest de Volharding [Perseverance Orchestra],

and in both of those cases, the whole underlying notion of the pieces

is who these people are who are going to be listening to it, and what my

relationship is to them. What do I understand about them as coming

to a concert thinking about the world, thinking about music, or thinking

about American music, and what is it I want them to know, or what is

it I want them to think about, or what is it I want to confront them with

in some way? That’s implicitly, or explicitly, something every

composer who writes for different audiences, has to think about.

I’ve been talking to other composers about this, and it seems to be something

that I’m not alone in thinking about. But in the case of the Indonesian

piece, I had to think a lot about what the average Balinese person know

about Western music. They thought that Western music was people

playing with a conductor. This is on a very surfaced level, but

it also goes into the actual nature of the music. In that case,

it was certain ideas about what Western musicians could do and couldn’t

do. They had to have a conductor, or they had to play with the printed

music, or they couldn’t interlock in the way Balinese instruments could.

I wanted to explode those notions, and so the piece was designed

around finding things that they’d be able to grab onto, as people not

understanding harmony, or Western notions of melody. So, there were

a lot of effects that the Western instruments were required to do that this

audience could understand, such as tremolos and pizzicatos, and just

the idea that would find more of the meaning of the music, and the surface

than the harmonic textures.

Ziporyn: Oh, absolutely. Since the last

time we really had a conversation, I’ve been involved more and more with

preparing performances for people in far-flung places. I did Aneh

Tapi Nyata, for gamelan and Western instruments [recording shown

at right], that was designed to be played at the Bali Arts Festival

for an audience of Balinese. Now I’m working on a piece for a Dutch

brass orchestra, the Orkest de Volharding [Perseverance Orchestra],

and in both of those cases, the whole underlying notion of the pieces

is who these people are who are going to be listening to it, and what my

relationship is to them. What do I understand about them as coming

to a concert thinking about the world, thinking about music, or thinking

about American music, and what is it I want them to know, or what is

it I want them to think about, or what is it I want to confront them with

in some way? That’s implicitly, or explicitly, something every

composer who writes for different audiences, has to think about.

I’ve been talking to other composers about this, and it seems to be something

that I’m not alone in thinking about. But in the case of the Indonesian

piece, I had to think a lot about what the average Balinese person know

about Western music. They thought that Western music was people

playing with a conductor. This is on a very surfaced level, but

it also goes into the actual nature of the music. In that case,

it was certain ideas about what Western musicians could do and couldn’t

do. They had to have a conductor, or they had to play with the printed

music, or they couldn’t interlock in the way Balinese instruments could.

I wanted to explode those notions, and so the piece was designed

around finding things that they’d be able to grab onto, as people not

understanding harmony, or Western notions of melody. So, there were

a lot of effects that the Western instruments were required to do that this

audience could understand, such as tremolos and pizzicatos, and just

the idea that would find more of the meaning of the music, and the surface

than the harmonic textures. BD: You’re teaching at MIT. Do you get enough time

to compose and perform?

BD: You’re teaching at MIT. Do you get enough time

to compose and perform?

Ziporyn: [With a broad smile] Even now, when I

sometimes feel I’ve heard it all, you can come across music which seems

quite ‘Martian’, and really extraordinary. It can either be from

some guy living down the block, or music being made in Hanoi, but it does

make me feel like there’s still a lot of ways of thinking about things,

and putting things together that are there to be discovered or created.

There’s more than enough of that left to find inside myself, and all over

the world, and maybe on other planets to keep me busy.

Ziporyn: [With a broad smile] Even now, when I

sometimes feel I’ve heard it all, you can come across music which seems

quite ‘Martian’, and really extraordinary. It can either be from

some guy living down the block, or music being made in Hanoi, but it does

make me feel like there’s still a lot of ways of thinking about things,

and putting things together that are there to be discovered or created.

There’s more than enough of that left to find inside myself, and all over

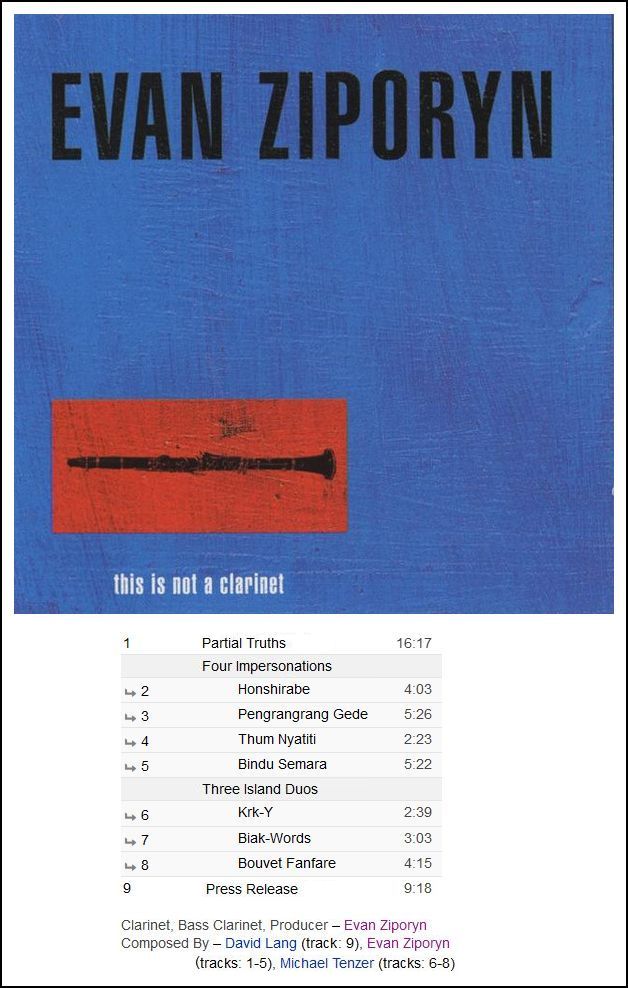

the world, and maybe on other planets to keep me busy. Ziporyn: Oh yes. All multi-phonics

grow out of extended techniques to expand the physical limitations

of the instrument. That’s true with electronic music, too.

Those are instruments with physical limitations, but there’s some relation

to the physicality of the sound. When I write music for the clarinet

that calls for a multiphonic, it’s a multiphonic that’s found in the

clarinet. It’s a product of what a clarinet can do.

Ziporyn: Oh yes. All multi-phonics

grow out of extended techniques to expand the physical limitations

of the instrument. That’s true with electronic music, too.

Those are instruments with physical limitations, but there’s some relation

to the physicality of the sound. When I write music for the clarinet

that calls for a multiphonic, it’s a multiphonic that’s found in the

clarinet. It’s a product of what a clarinet can do.These conversations was recorded in Chicago on August 18, 1989, and September 5, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1994, 1998, and 1999; and on WNUR in 2004, with a podcast available in 2010. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website om 2020. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.