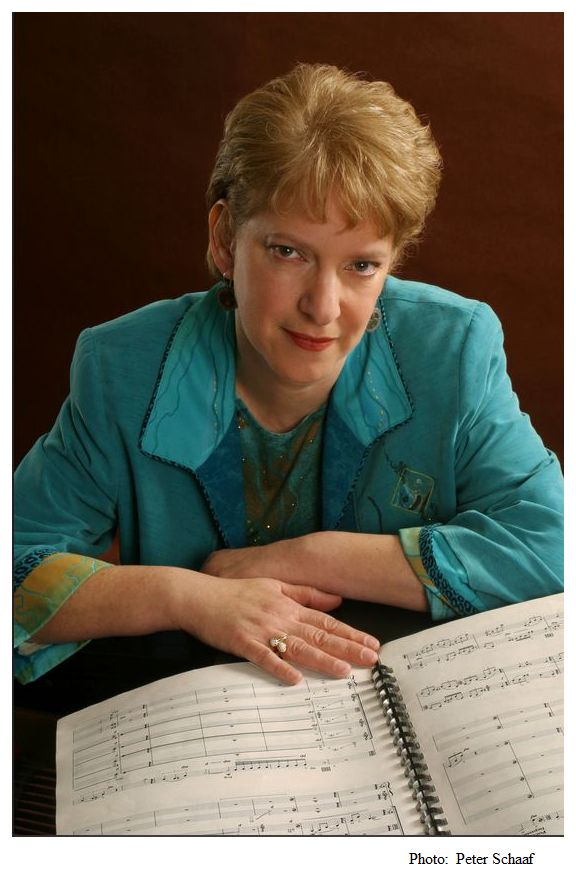

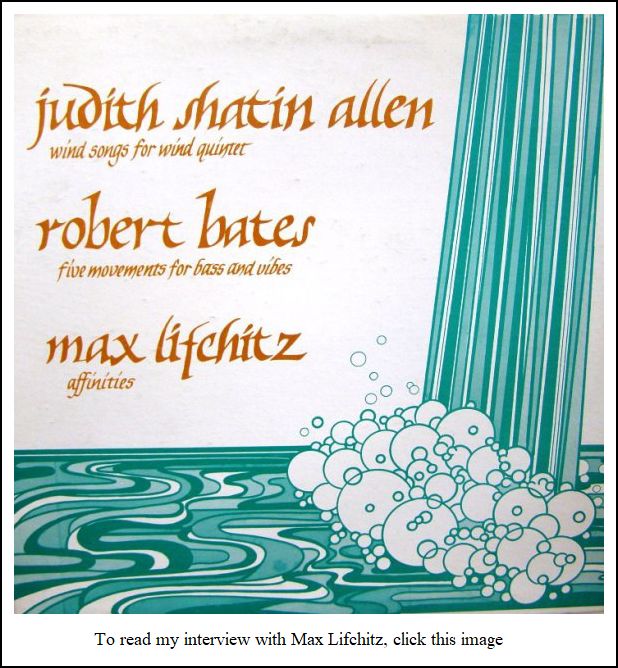

A well-respected composer working in many musical genres, Judith Shatin Allen is a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Douglass College, as well as a recipient of the M.M. from Juilliard School and a Ph.D. from Princeton. Among her awards are two NEA Composer Fellowships, a Chamber Opera Commission from the Ash Lawn Summer Festival, a New Jersey State Arts Council Grant, and awards from "Meet the Composer" and the American Music Center.

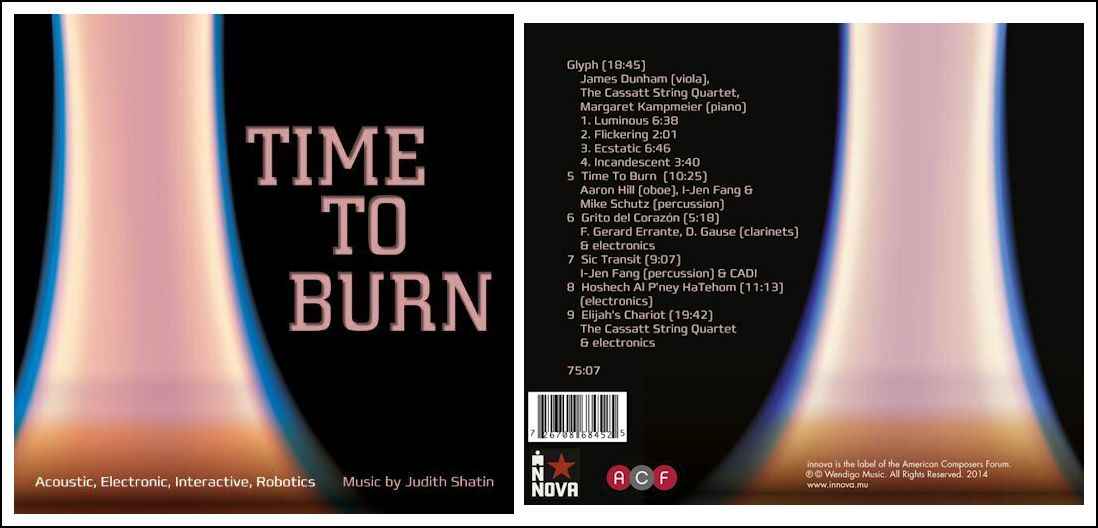

Her works have been performed by the Houston Symphony, the Da Capo Chamber Players, the Contemporary Music Forum, the E.A.R. Ensemble, and the Sylvan and Clarion Wind Quintets. Her Icarus, for violin and piano, was performed at the National Gallery's American Music Festival in Washington, D.C., and her Glyph, for viola, string quartet, and piano, was premiered at the Thirteenth International Viola Congress in Boston.

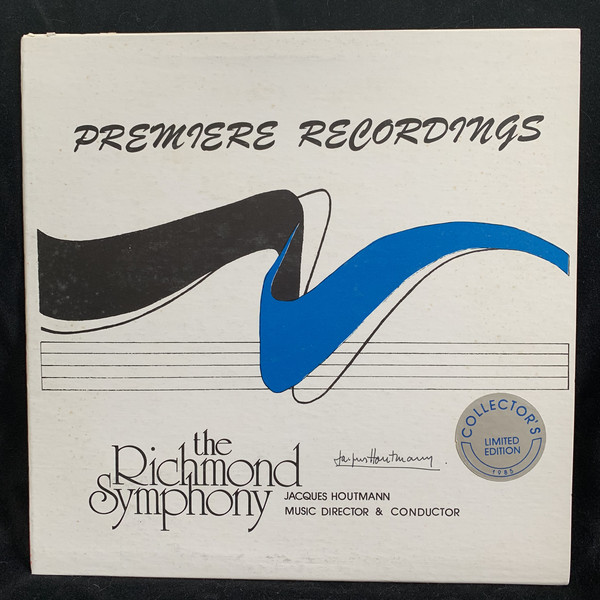

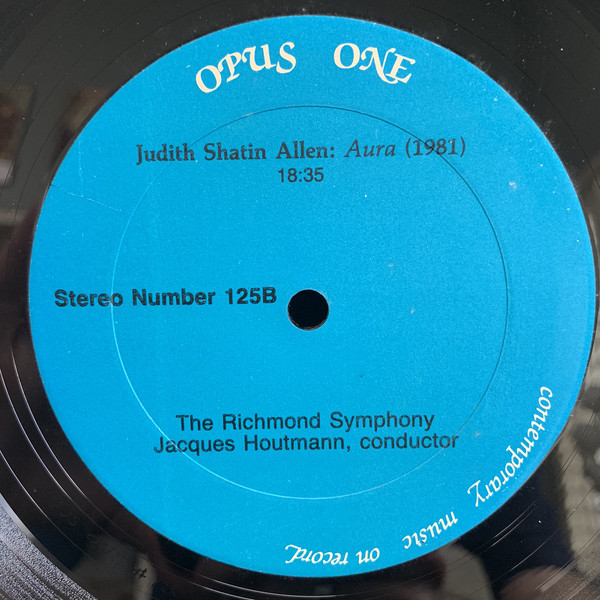

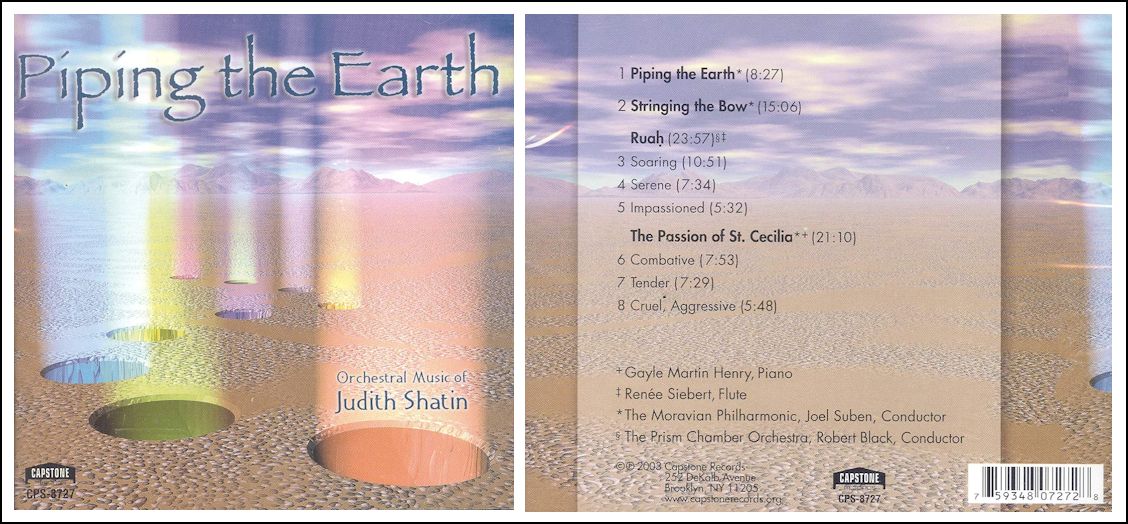

Her Aura, for orchestra,

was composed under an NEA Composer Fellowship in 1981, premiered in

1982 by the Charlottesville University and Community Orchestra. It was

subsequently performed and recorded by the Richmond Symphony under the

Direction of Jacques Houtmann in 1985. This recording is available on

vinyl from Opus One Records.

Aura is a large-scale work of just under twenty

minutes' duration. The basic musical material derives from a tone-row

chosen for its whole-tone characteristics. According to the composer, "The

surface of the piece focuses on small subgroups from the underlying row,

with a resultant tonal quality; Aura also refers to traditional

form in its dramatic use of transposed recurrent themes which reach a state

of resolution at its close."

The work has a distinct post-romantic quality while maintaining a tonally-flexible freedom; the composer effectively manipulates orchestral timbres to create a mystical aura consisting of clouds of sound materials. As the composer explained, "Just as every verbal utterance has its own tone of voice, its affective extension, so does every sound. It is this ineffable extra that Aura celebrates."

BD: You’re both composer and teacher.

How do you balance those two very taxing activities?

BD: You’re both composer and teacher.

How do you balance those two very taxing activities? JS: I did, but I didn’t want

to embarrass them. When one is a composer and not performing oneself,

one basically is putting one’s work in the hands of the performers. So,

I feel I have to trust them at that point.

JS: I did, but I didn’t want

to embarrass them. When one is a composer and not performing oneself,

one basically is putting one’s work in the hands of the performers. So,

I feel I have to trust them at that point.

JS: All of the above. Whether

one likes it depends on the piece. As a good example from the art

world, if you go and look at a work by Egon Schiele, it’s very powerful

and strong. Does that mean you like it? [Egon Schiele (12

June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian painter. A protégé

of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early

20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality,

and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits.

The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's

paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.]

I certainly am not interested in just creating, or having

to respond to music that is in some measurable way ‘pretty’. I

would like for it to be powerful, and to have many different kinds of

qualities.

JS: All of the above. Whether

one likes it depends on the piece. As a good example from the art

world, if you go and look at a work by Egon Schiele, it’s very powerful

and strong. Does that mean you like it? [Egon Schiele (12

June 1890 – 31 October 1918) was an Austrian painter. A protégé

of Gustav Klimt, Schiele was a major figurative painter of the early

20th century. His work is noted for its intensity and its raw sexuality,

and the many self-portraits the artist produced, including naked self-portraits.

The twisted body shapes and the expressive line that characterize Schiele's

paintings and drawings mark the artist as an early exponent of Expressionism.]

I certainly am not interested in just creating, or having

to respond to music that is in some measurable way ‘pretty’. I

would like for it to be powerful, and to have many different kinds of

qualities.

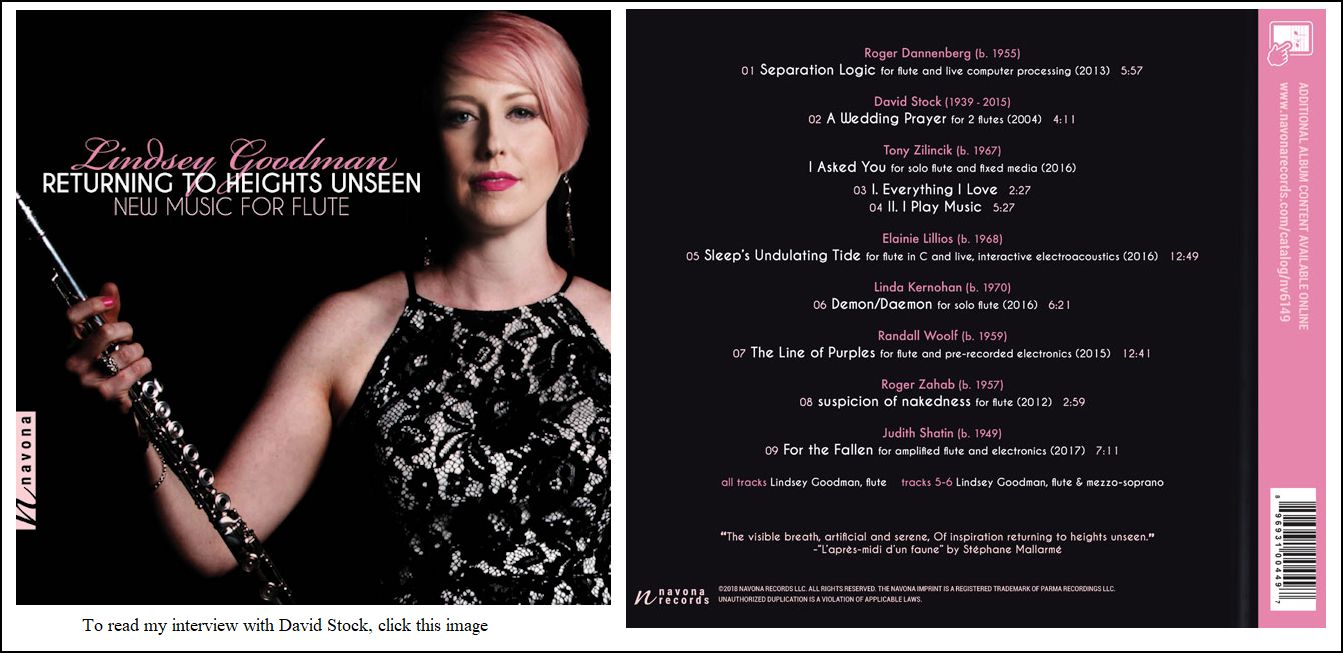

JS: Typically, I have found them. For

instance, I did a piece for the San Francisco Girls Chorus, for treble

chorus and electronics, and I found special poems by Gertrude Stein, Ogden

Nash, Walter de la Mare, and Mary Ann Hoberman. I spent months looking

at poems in order to find those.

JS: Typically, I have found them. For

instance, I did a piece for the San Francisco Girls Chorus, for treble

chorus and electronics, and I found special poems by Gertrude Stein, Ogden

Nash, Walter de la Mare, and Mary Ann Hoberman. I spent months looking

at poems in order to find those.

BD: Do you then spread the piece out,

or use the material in two pieces?

BD: Do you then spread the piece out,

or use the material in two pieces?