| In 1979 James Sedares (born January 15, 1956) was

appointed Associate Conductor and later Music Advisor of the San Antonio

Symphony. He joined the Phoenix Symphony as Resident Conductor in 1986

and three years later became its Music Director. In this latter position,

he has made a distinguished name for himself as one of the most outstanding

of a new generation of American conductors. He has enjoyed equal acclaim

as a guest conductor in the United States and abroad, the latter engagements

including appearances with major orchestras in Europe, in Central and Southern

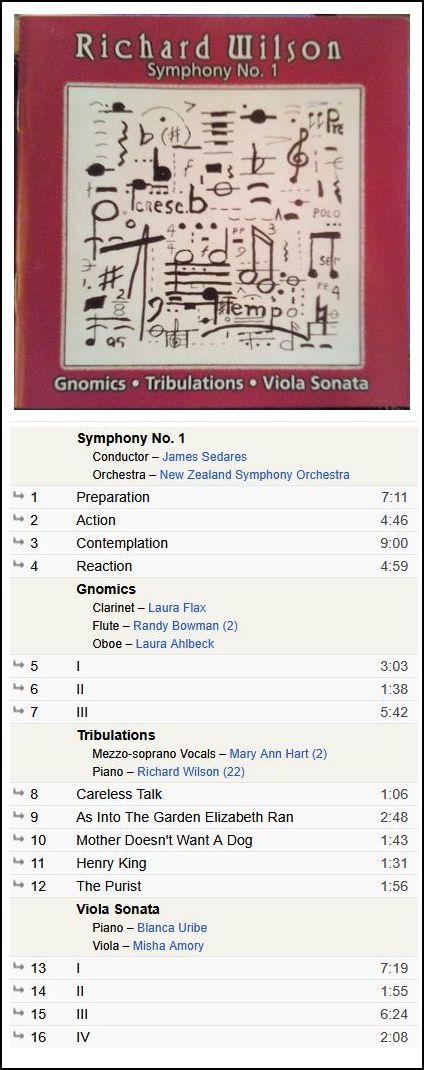

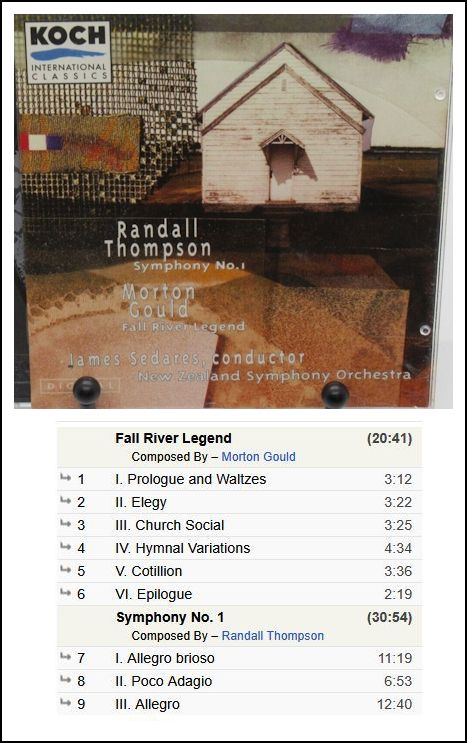

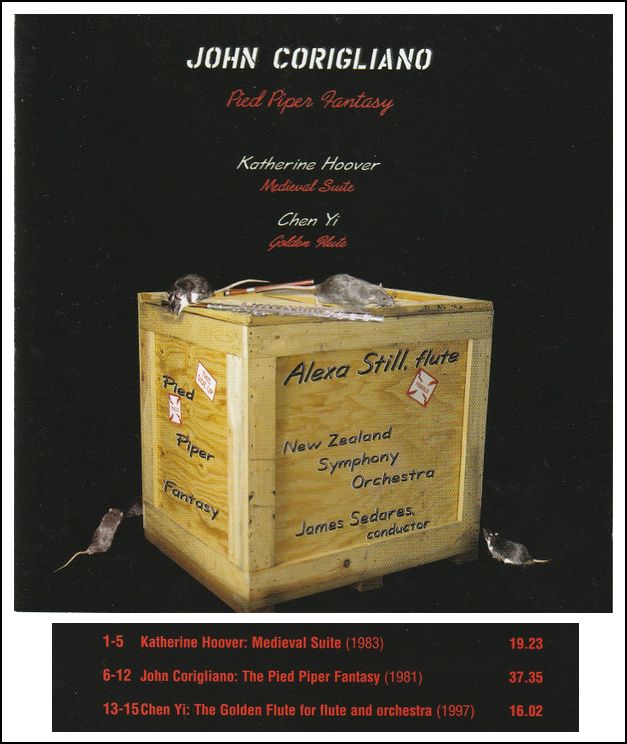

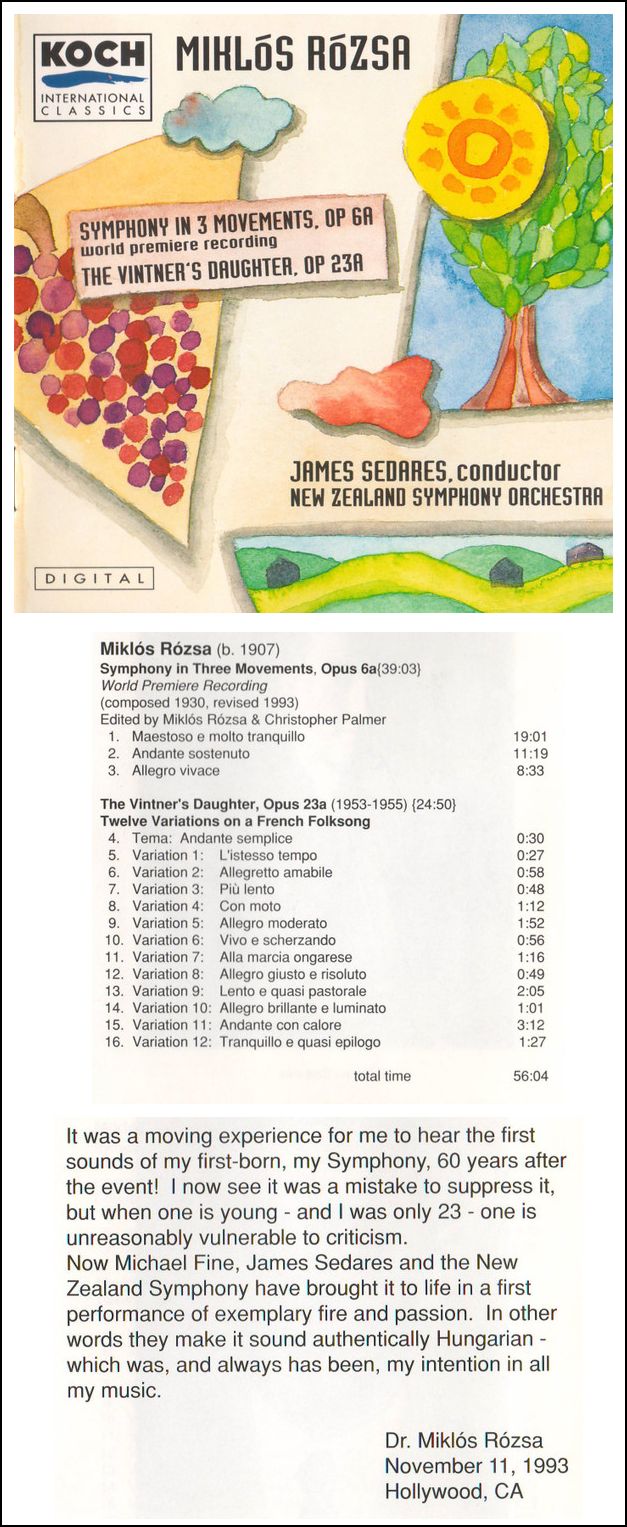

America, and in New Zealand. His recordings include Grammy-nominated releases with the London Symphony Orchestra and with the Louisville Orchestra, and a series of some fifteen recordings with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. With the Phoenix Symphony he has won particular success in the recording studio, with acclaimed award-winning releases, in particular, of works by leading American composers. == Biography above is from the Naxos website

== Biography below is from the Summit Records website * * *

* *

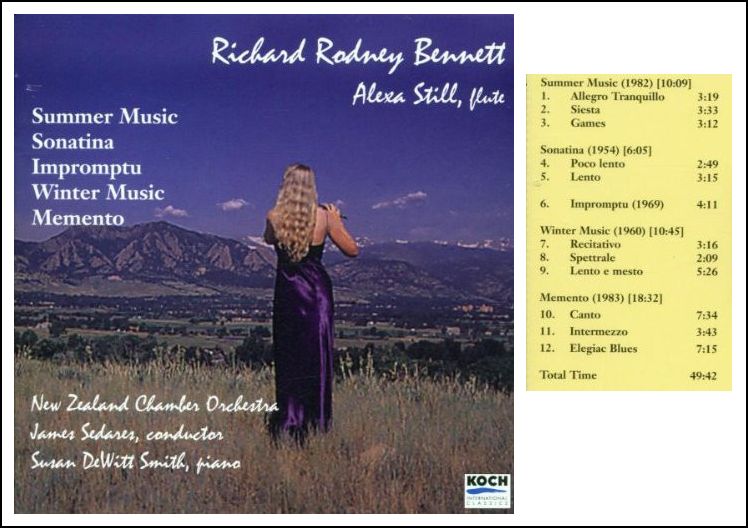

The American conductor, James Sedares, has proven himself one of the best and the brightest of a new generation of American conductors. In 1996 he concluded a ten-year tenure with the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra, an ensemble he placed into the spotlight of national and international recognition. Responding to a performance conducted by Maestro Sedares, the Arizona Republic stated, “If quality and beauty are criteria for attending a concert, patrons should be standing in line to get into Symphony Hall…” An impressive orchestra builder, James Sedares recently concluded his 6th season in the position of Principal Guest Conductor with the Vector Wellington Orchestra in Wellington, New Zealand (2006). Last season he made his debut with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and had his first release on the prestigious Deutsche Grammophon Label in a performance of the Waxman oratorio Joshua performed with the Prague Philharmonia. Upcoming debuts include performances in Mumbai, London, and Seoul. An active recording artist, James Sedares led The Phoenix Symphony’s critically acclaimed premiere recording of Copland works released on the Koch International Classics label in September 1991, later winning the prestigious INDIE award for best classical album of the year from the National Association of Independent Record Distributors (NAIRD). Sedares’s second recording with the Phoenix Symphony featuring works of William Schuman and Bernard Herrmann, appeared on the Billboard classical album charts for several months and the 1999 release of former PSO Composer-In-Residence Daniel Asia’s Symphonies Nos. 1 and 2 on New World Records received stunning critical acclaim in the recording press. Undoubtedly the foremost success for Sedares and the Orchestra was the recording of Elmer Bernstein’s reconstructed score to The Magnificent Seven on Koch International Classics in 1994. This blockbuster CD was listed on Billboard Magazine’s classical crossover best seller chart and continues to be one of the top rated releases of the year. The composer calls it “the definitive interpretation” and it won the ECHO Award, the prestigious German Record Critics Prize (Der Deutschen Schallplattenkritik Preise); as well as another INDIE award as best CD in the film music category. Another recent film score recording on Koch is that of Miklós Rózsa’s El Cid with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. James Sedares’s collaboration with the Koch International label

includes two Grammy-nominated recordings: one with the London Symphony Orchestra

and the other with the Louisville Orchestra. Sedares has recorded over

40 projects for release on Koch International Classics. He has nearly 30

recordings with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra and the New Zealand Chamber

Orchestra. A recent release on Universal Music NZ entitled “Beauty Spot” with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra achieved gold status and topped the charts, sharing this spot with many of today’s most recorded Pop artists. “Beauty Spot II” was released in 2002 and is still topping the NZ charts. An active guest conductor, James Sedares has led many of the major orchestras throughout Europe, the Pacific Rim and the USA. == Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

See my interviews with Norman Dello Joio,

and Andrew Schenck

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 21, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following March, and again in 1998; on WNUR in 2011, and 2015; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2011. This transcription was made at the end of 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.