A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

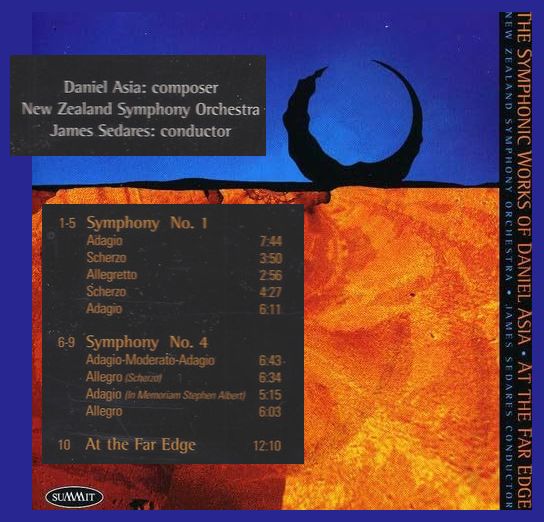

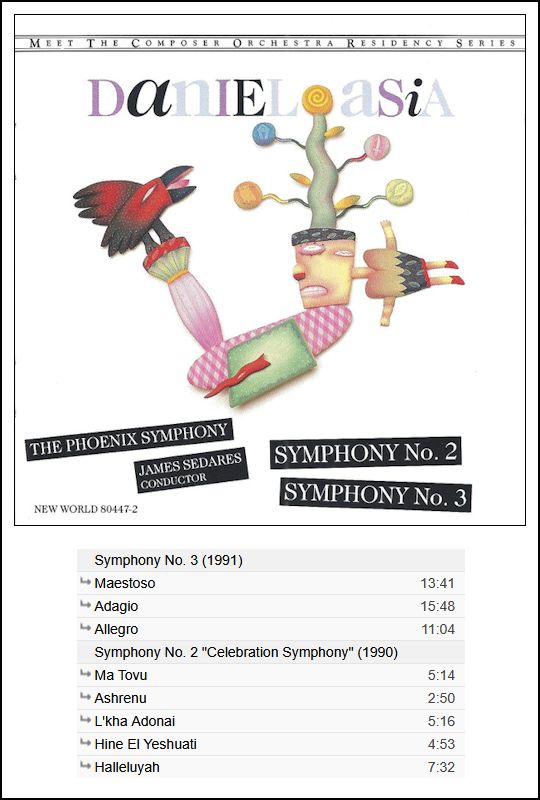

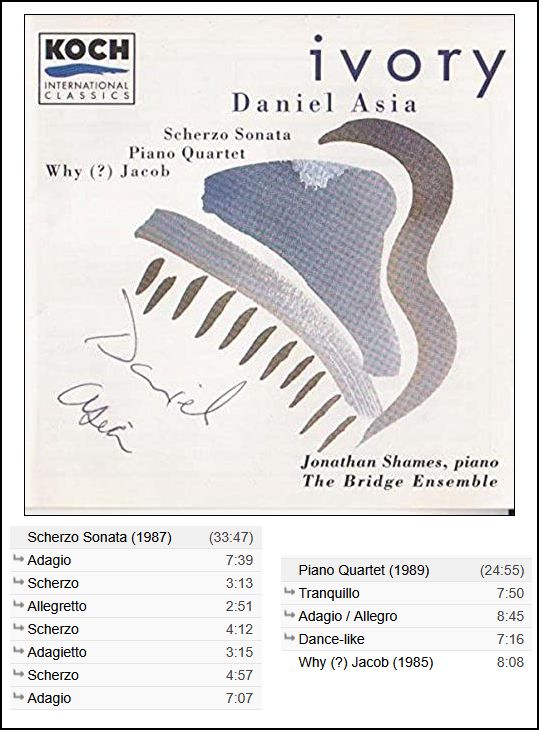

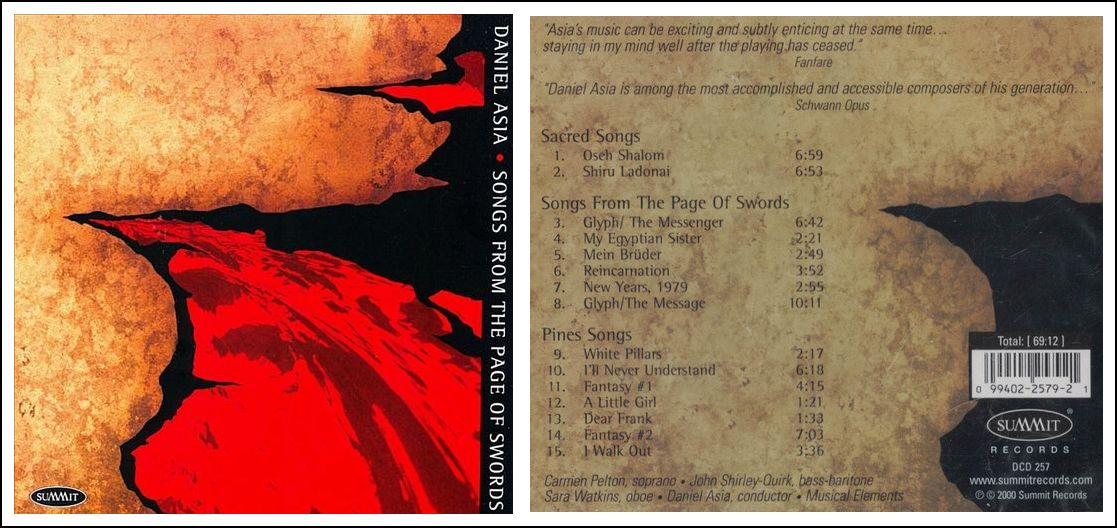

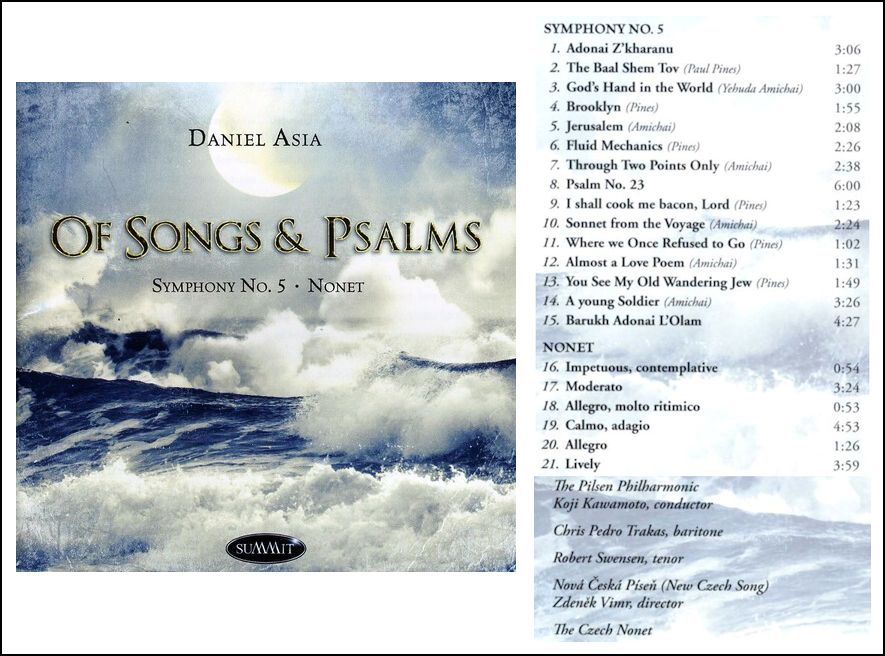

Daniel Asia (born June 27, 1953) is an American composer. Born in Seattle, Washington, he received a B.A. degree from Hampshire College and a M.M. from the Yale School of Music. His major teachers include Jacob Druckman, Stephen Albert, Gunther Schuller, and Isang Yun in composition, and Arthur Weisberg in conducting. Asia's works ranges from solo pieces to large-scale multi-movement works for orchestra, including five symphonies. He served on the faculty of the Oberlin Conservatory of Music as Assistant Professor of Contemporary Music and Wind Ensemble from 1981 to 1986. In 1986–88, a UK Fulbright Arts Fellowship and a Guggenheim Fellowship enabled him to work in London as a visiting lecturer at City University. Since 1988, he has been Professor of Composition and head of the composition department at the University of Arizona in Tucson. He conducts the New York-based contemporary chamber ensemble The Musical Elements, which he co-founded in 1977. Asia founded and directs the American Culture and Ideas Initiative. Asia contributes articles on music and culture to The Huffington Post. His orchestral works have been commissioned or performed by the symphony

orchestras of Cincinnati, Seattle, Milwaukee, New Jersey, Phoeniz, American

Composers Orchestra (New York City, Columbus (Ohio), Grand Rapids, Jacksonville,

Chattanooga, Memphis, Tucson, Knoxville, Greensboro, Seattle Youth, Brookly,

Colorado, and Pilsen (Czech Republic). Conductors include Zdenek Macal, Jesús López-Cobos,

Eiji Oue, Lawrence Leighton

Smith, Hermann Michael,

Carl St. Clair, James

Sedares, Stuart Malina, Robert Bernhardt, George Hanson, Jonathan Shames,

Odaline de la Martinez, Kirk Trevor, Koji Kawamoto, and Christopher Kendall.

== Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

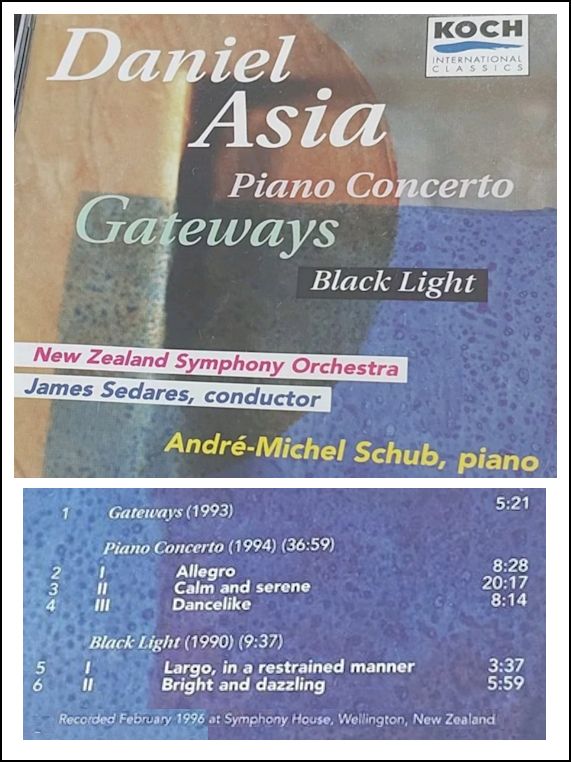

| I am here in Milwaukee, and this is

an all-American program, and it’s pretty tough.

The Samuel Barber Essay for Orchestra, most orchestras know

well, but Daniel Asia’s Piano Concerto is a brand new piece,

and it’s long. It’s not terribly hard for the orchestra, but it’s

very hard for the pianist. Our pianist, André-Michel Schub,

is wonderful. He plays non-stop practically for the whole piece.

The orchestra backs him more than actually having many tuttis.

But it is long, about forty-five minutes. Then, the Aaron Copland

Third is one of the most difficult in the repertory. == From my interview with Lawrence Leighton

Smith

|

© 1996 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on April 12, 1996. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1998, and on WNUR in 2002, 2006, and 2017. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.