Donald Martino: Well, that’s a real problem.

It seems to be going ever downward.

Donald Martino: Well, that’s a real problem.

It seems to be going ever downward. DM: If I divided my time just between teaching and

composing, I would have enough time. But I’ve undertaken various other

things, such as music publishing, and that has taken a tremendous amount

of time. But just about anybody who’s engaged in teaching and is also

composing, would probably feel that he finds enough time to compose.

Teaching is a rewarding profession. Obviously it’s a profession that’s

stimulating, and from which one learns a great deal just in dealing with

students’ problems and trying to come up with answers to their problems.

Often times one comes up with an idea that’s fascinating and feeds your own

work.

DM: If I divided my time just between teaching and

composing, I would have enough time. But I’ve undertaken various other

things, such as music publishing, and that has taken a tremendous amount

of time. But just about anybody who’s engaged in teaching and is also

composing, would probably feel that he finds enough time to compose.

Teaching is a rewarding profession. Obviously it’s a profession that’s

stimulating, and from which one learns a great deal just in dealing with

students’ problems and trying to come up with answers to their problems.

Often times one comes up with an idea that’s fascinating and feeds your own

work. DM: It’s a little hard to generalize on it, but

it’s a process that involves a certain amount of what might be called improvisation,

and a certain amount of inspection or analysis. The entire piece doesn’t

just come in a blaze of light, and neither is it only the product of hard

labor. It’s some sort of mixture. Usually, for me, the initial

idea is a kind of an improvised idea, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that

it’s easily come by. I might sit in this sort of vacuum of the study,

where I am right now, with the project ahead of me. I have to write

such-and-such a piece for such-and-such an ensemble. I begin to try

to conjure up what that might mean to me at this moment in my life.

Take String Quartet, for example.

It meant something to me at twenty-three that it doesn’t mean to me at sixty.

I try to conjure up what that means.

DM: It’s a little hard to generalize on it, but

it’s a process that involves a certain amount of what might be called improvisation,

and a certain amount of inspection or analysis. The entire piece doesn’t

just come in a blaze of light, and neither is it only the product of hard

labor. It’s some sort of mixture. Usually, for me, the initial

idea is a kind of an improvised idea, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that

it’s easily come by. I might sit in this sort of vacuum of the study,

where I am right now, with the project ahead of me. I have to write

such-and-such a piece for such-and-such an ensemble. I begin to try

to conjure up what that might mean to me at this moment in my life.

Take String Quartet, for example.

It meant something to me at twenty-three that it doesn’t mean to me at sixty.

I try to conjure up what that means. DM: Yes. I’ve had some just fabulous performances!

This was not always true. I first started composing in the forties,

and then in college and out as a young professional, the performance situation

was pretty terrible and performances were quite awful. But beginning

with the seventies, or maybe the late sixties, I began to get performances

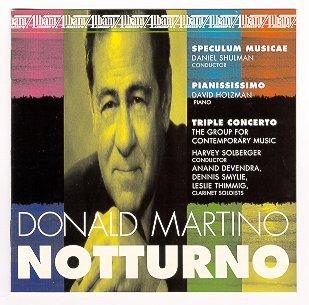

that were just phenomenal. The performance that I got from Speculum

Musicae in 1973 of my Notturno is,

I think, just a spectacular performance. It’s wonderful to be able

to get a premiere like that, and they got it on disk immediately. And

my Triple Concerto in 1979 was also

just a fantastic performance! I went to the first rehearsal that I

was invited to — after the ensemble had practiced for

a few weeks, I guess — and I went with some fear, because

it’s a difficult piece. I had no idea what was up or what I would find,

and I was just amazed! They played so well that I wondered why I had

committed myself to a week of rehearsals with them! I wasn’t necessary,

and that was to some extent because the players were so experienced and so

good. Also because of the conductor, Harvey Sollberger,

who is just a wonderful interpreter of new music.

DM: Yes. I’ve had some just fabulous performances!

This was not always true. I first started composing in the forties,

and then in college and out as a young professional, the performance situation

was pretty terrible and performances were quite awful. But beginning

with the seventies, or maybe the late sixties, I began to get performances

that were just phenomenal. The performance that I got from Speculum

Musicae in 1973 of my Notturno is,

I think, just a spectacular performance. It’s wonderful to be able

to get a premiere like that, and they got it on disk immediately. And

my Triple Concerto in 1979 was also

just a fantastic performance! I went to the first rehearsal that I

was invited to — after the ensemble had practiced for

a few weeks, I guess — and I went with some fear, because

it’s a difficult piece. I had no idea what was up or what I would find,

and I was just amazed! They played so well that I wondered why I had

committed myself to a week of rehearsals with them! I wasn’t necessary,

and that was to some extent because the players were so experienced and so

good. Also because of the conductor, Harvey Sollberger,

who is just a wonderful interpreter of new music. DM:

Yes, sure, they could go back to the original tape and redo it, if

anybody cared. But that’s probably not going to happen, so it’ll remain

in this version.

DM:

Yes, sure, they could go back to the original tape and redo it, if

anybody cared. But that’s probably not going to happen, so it’ll remain

in this version. DM: Yes, and then, of course, you have that other

audience. Let’s say some new music group from New York or Boston

— the Musica Viva or Collage, or some other music ensemble

— come to Boston to do a concert in Sanders Theater at Harvard.

Maybe a couple hundred people would show up. Fine! That’s very

nice. If we have the Kronos Quartet come, you have to turn people away!

The Kronos plays Jimi Hendrix and stuff like this, which of course draws

a kind of a crowd! I have nothing against Jimi Hendrix. I have

nothing against popular music, which I spent most of my childhood doing,

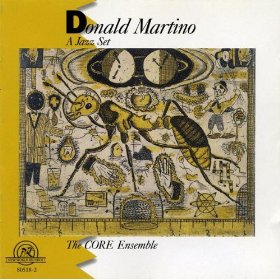

and still am very interested in! I was a jazz clarinetist; I played

all over Europe and this country. I have a deep interest and commitment

in popular music of all kinds.

DM: Yes, and then, of course, you have that other

audience. Let’s say some new music group from New York or Boston

— the Musica Viva or Collage, or some other music ensemble

— come to Boston to do a concert in Sanders Theater at Harvard.

Maybe a couple hundred people would show up. Fine! That’s very

nice. If we have the Kronos Quartet come, you have to turn people away!

The Kronos plays Jimi Hendrix and stuff like this, which of course draws

a kind of a crowd! I have nothing against Jimi Hendrix. I have

nothing against popular music, which I spent most of my childhood doing,

and still am very interested in! I was a jazz clarinetist; I played

all over Europe and this country. I have a deep interest and commitment

in popular music of all kinds. BD:

Is that more pressure?

BD:

Is that more pressure?

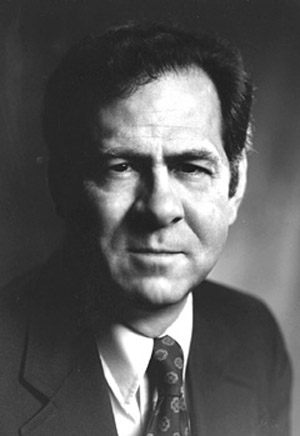

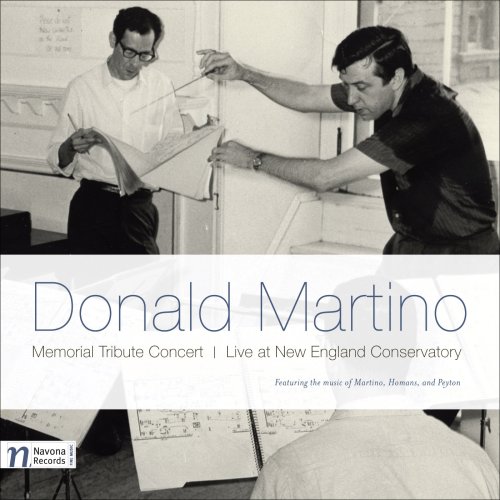

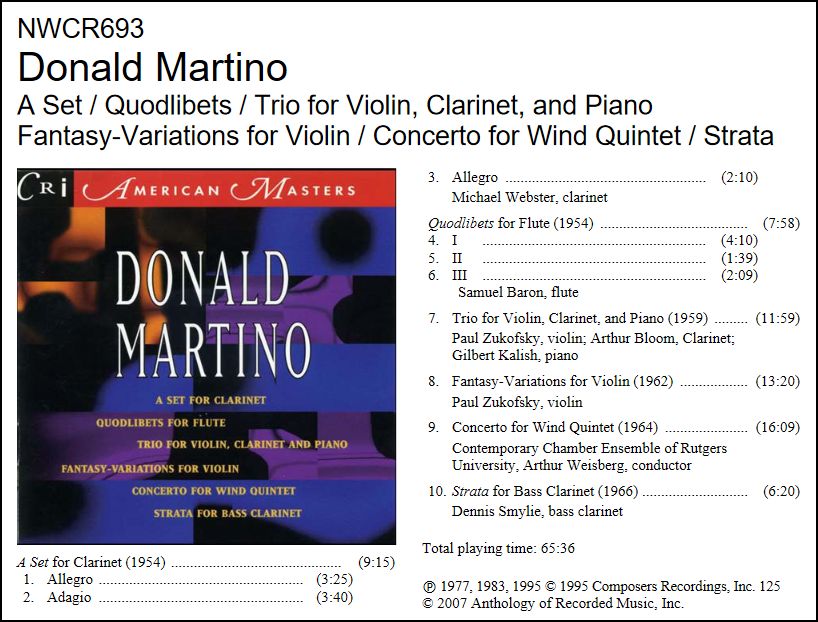

Donald Martino, 74, Pulitzer-winning composer, teacher at local collegesDonald Martino, the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer who lived in Newton, died Thursday off the coast of Antigua while on a Caribbean cruise. The cause of death was cardiac arrest following an attack of hyperglycemia. He was 74. Mr. Martino was a prominent presence in Boston's musical life since he began teaching at New England Conservatory in 1969. In 1980, he took a post at Brandeis University, and from 1983 until his retirement from teaching in 1993 he taught at Harvard University. A composer of meticulous craftsmanship, he used his prodigious technical skills and rigorous attention to detail to produce music that sounds spontaneous and emotionally immediate.

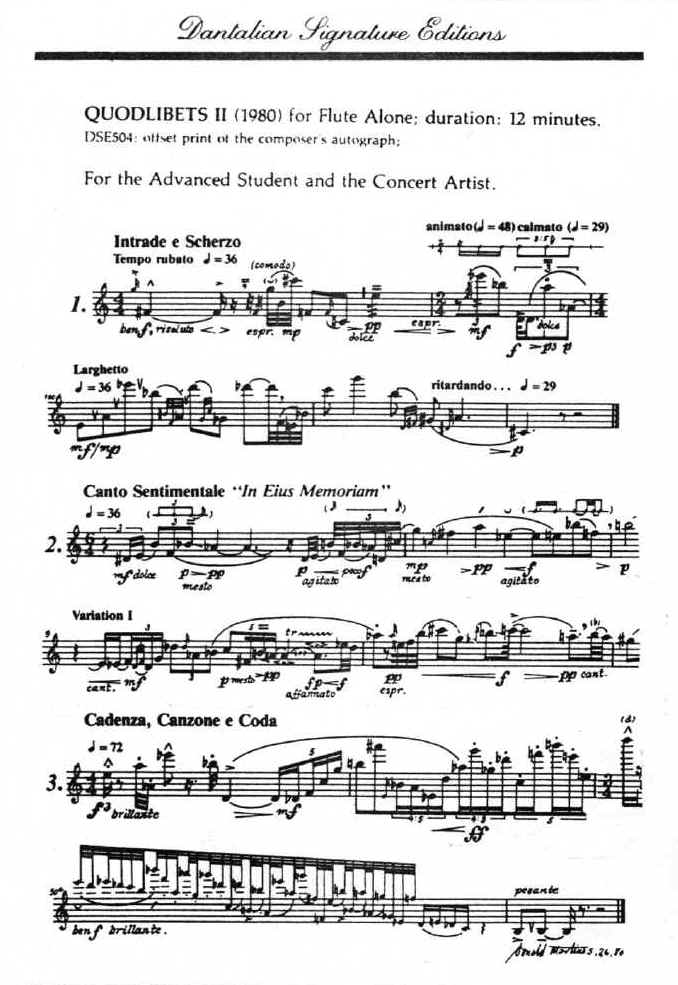

Mr. Martino loved many kinds of music -- jazz, Tin Pan Alley, opera, the great 19th-century virtuoso showpieces for clarinet, and the works of the composers of Second Viennese School, Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, and their Italian successor Luigi Dallapiccola, with whom he studied in Florence on a Fulbright Fellowship in the mid-1950s. A listener can hear all of these influences in his work, but only Mr. Martino could have written his music, which is sensuous and serious, even when it is playful or even cheeky, as in ''Dr. Schoenberg's Magic Cabaret." He composed industriously for six decades, and even in recent years, when he was dogged by poor health, he continued to write. He created a publishing company, Dantalian Music, to issue his own music. Dantalian's ''shipping department" is a plywood counter that folds down over the washer and dryer in the basement of his home. Mr. Martino took a computer and a portable keyboard with him on the cruise and spent most of his last day working on a commission from the Tanglewood Music Center for a Concertino for Violin and 14 Instruments, said his wife, Lora (Harvey) yesterday. ''We've taken cruises for many years now; it was our vacation mode," said his wife. ''He liked to sit in a room writing music. I like to be out and active in the sunshine. On a cruise, we could do that. On his last day he worked until 4 p.m." His last completed work was a Concerto for Orchestra, finished last summer. Mr. Martino was born in Plainfield, N.J. His first instrument was the clarinet, which he played both in jazz groups and symphony orchestras; he also played oboe and saxophone. He wrote major works for piano, but according to his friend and fellow composer Yehudi Wyner, he played the instrument with three fingers -- two in the right hand, one in the left, for the bass. At the time of Mr. Martino's retirement, Wyner produced a short piano piece in tribute called, ''ThreeFingered Don." ''He was a relentless worker of the highest standard," said Wyner. ''He had a very catholic view of things and great personal generosity; he was able to appreciate the aesthetic positions of other composers." Mr. Martino studied at Syracuse University and at Princeton, where his mentors included composers Milton Babbitt and Roger Sessions. Mr. Martino taught at Princeton, Yale, and the Tanglewood Music Center before coming to Boston. Under the name ''Jimmy Vincent," he wrote several pop songs that never became popular. ''They were too original to become popular -- wayward, inventive, always interesting; you keep stubbing your toe," said Wyner. Mr. Martino's largest work, composed on the scale of Mahler's ''Symphony of a Thousand," was ''Paradiso Choruses," an ecstatic setting of lines from the final section of Dante's ''Divine Comedy" premiered in 1975 at New England Conservatory. It calls for chorus, children's chorus, large orchestra, tape, and 14 soloists. The premiere was conducted by Lorna Cooke de Varon. ''For my 25th year at the Conservatory, I was given a present -- the opportunity to commission a new work," recalled de Varon yesterday. ''I asked Don for a small work for chorus and orchestra, and Donald came forth with this extraordinary thing. To prepare it was a fascinating and wonderful experience, and in a sense he stage-directed the whole performance, deciding where everyone would stand and sit. He was a perfectionist -- but not the kind that has a temper." His 1974 Pulitzer Prize came for ''Notturno," a work for flute, clarinet, violin cello, and piano, a work of night moods, night fantasies. In 1987 he wrote a Saxophone Concerto premiered by Kenneth Radnofsky. ''He was a man of uncompromising artistic integrity who heard every note he wrote; he was Brahms, working in a modern idiom," said Radnofsky yesterday. Mr. Martino's most recent Boston premiere was early this year when conductor Gil Rose led clarinetist Ian Greitzer in the premiere of his luminous "Concertino for Clarinet and Orchestra" at a concert by the Boston Modern Orchestra Project last season. ''His music lost none of its complexity but it became more straightforward -- a little like the man himself," said Rose. ''He took no prisoners when he was dealing with music, but he became more and more congenial in human relations as he aged. He always knew exactly what he wanted." In addition to his wife, he leaves a daughter, Anna Maria of Branford, Conn., and a son, Christopher of Boston. Plans for a memorial event are not complete. © Copyright 2006 Globe Newspaper Company.

Obituary from The Boston

Globe (with links added)

|

This interview was recorded on the telephone on January 12, 1991.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in later that year and

again in 1996. This transcription was made and posted on this website

in 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.