|

Barbara Ann Martin graduated from the Juilliard School in New York after completing both her Bachelor's and Master's Degrees in Voice and Opera Theater. Some of her mentors were also individuals that she studied with, including Florence Page Kimball, Alice Howland, Antonia Lavanne, Cornelius Reid, James Carson, and Susan Charles. Martin has a passion and natural talent for voice, but specializes in classical and music theater voice training. Her achievements stem far and wide, as she has performed all

throughout the United States, Europe and Asia, and made appearances

at various music festivals such as Aspen, Boulder, Ravinia, Caramoor,

Huddersfield, Adelaide, and Salzburg. In addition to this, she was an

apprentice at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, and the Central City

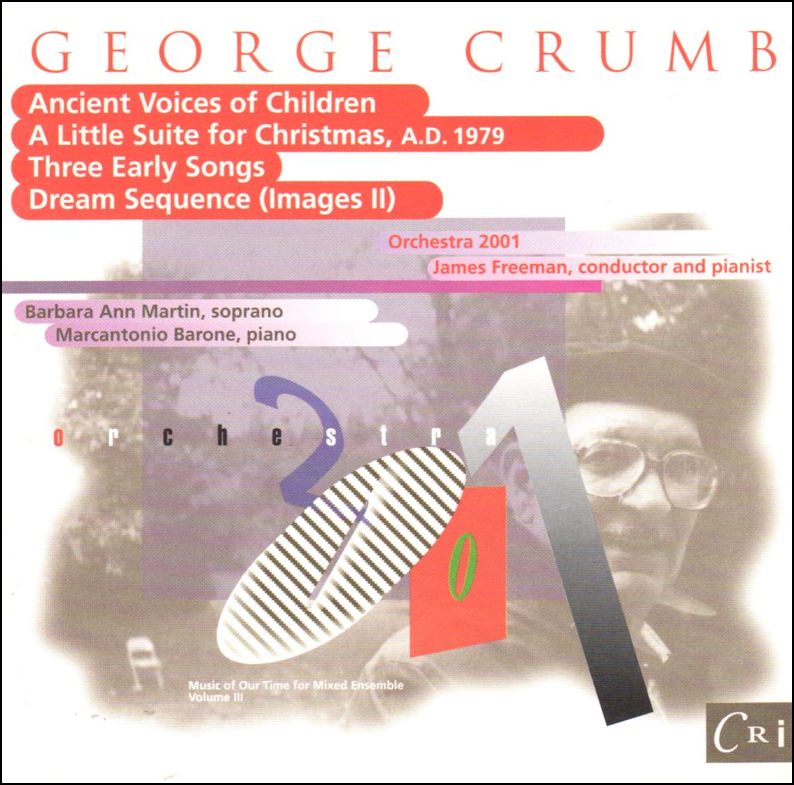

opera Company in Colorado. She has sung composer George Crumb's master-work,

"Ancient Voices of Children" with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the

Berlin and New York Philharmonics, the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, the

Maggio Musicale, the Montreal Symphony, and the Israel Philharmonic to

critical acclaim (as well as the recording shown below).

She has had several opera appearances, which include the

Metropolitan, Chicago, Central City, New Jersey State, and Minnesota Operas.

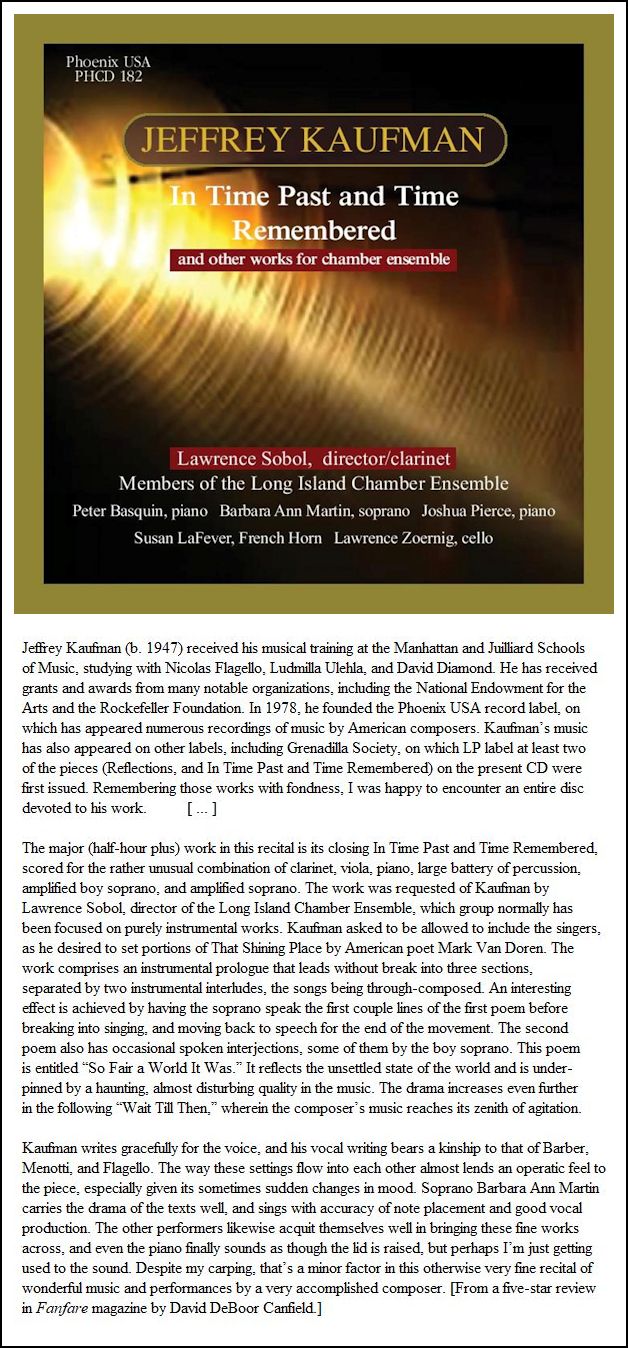

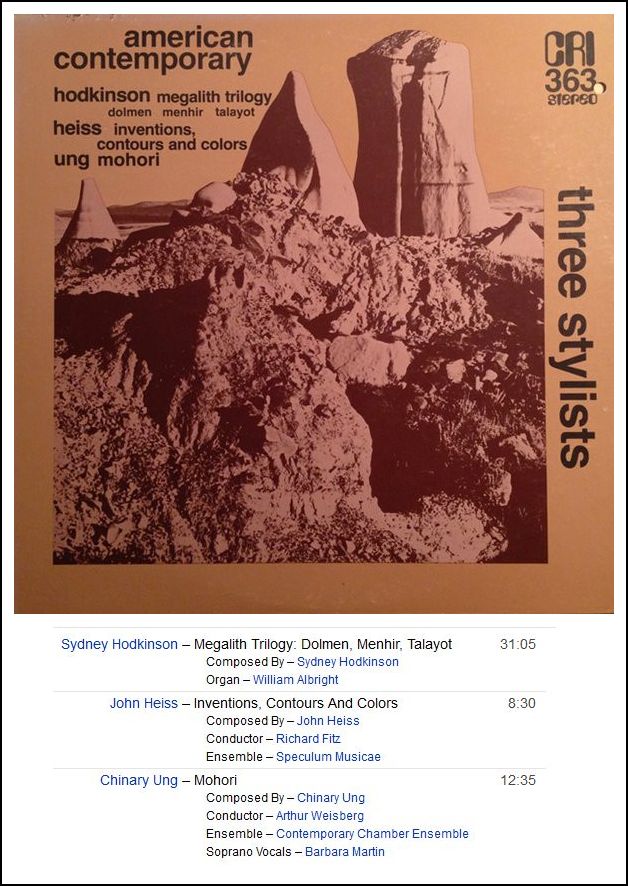

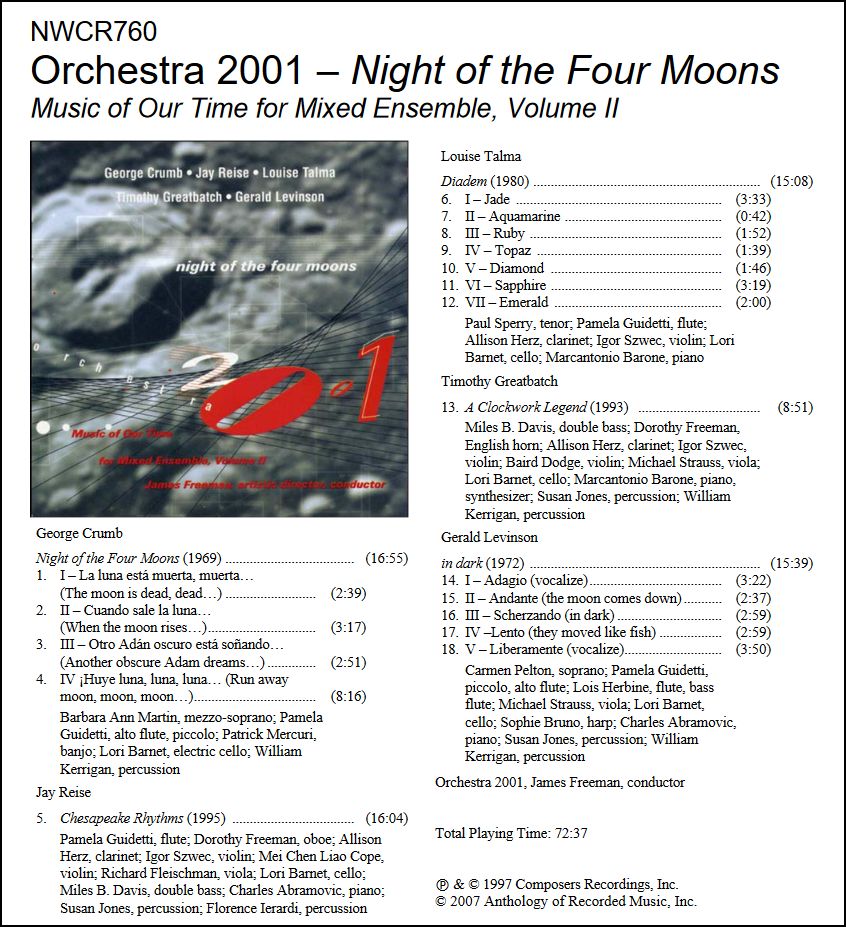

Several of Martin's recordings feature works by Dominick Argento, Milton Babbitt, Crumb,

Alan Hovhanness,

Karel Husa,

George Rochberg,

Augusta Read Thomas,

Virgil Thomson,

Louise Talma,

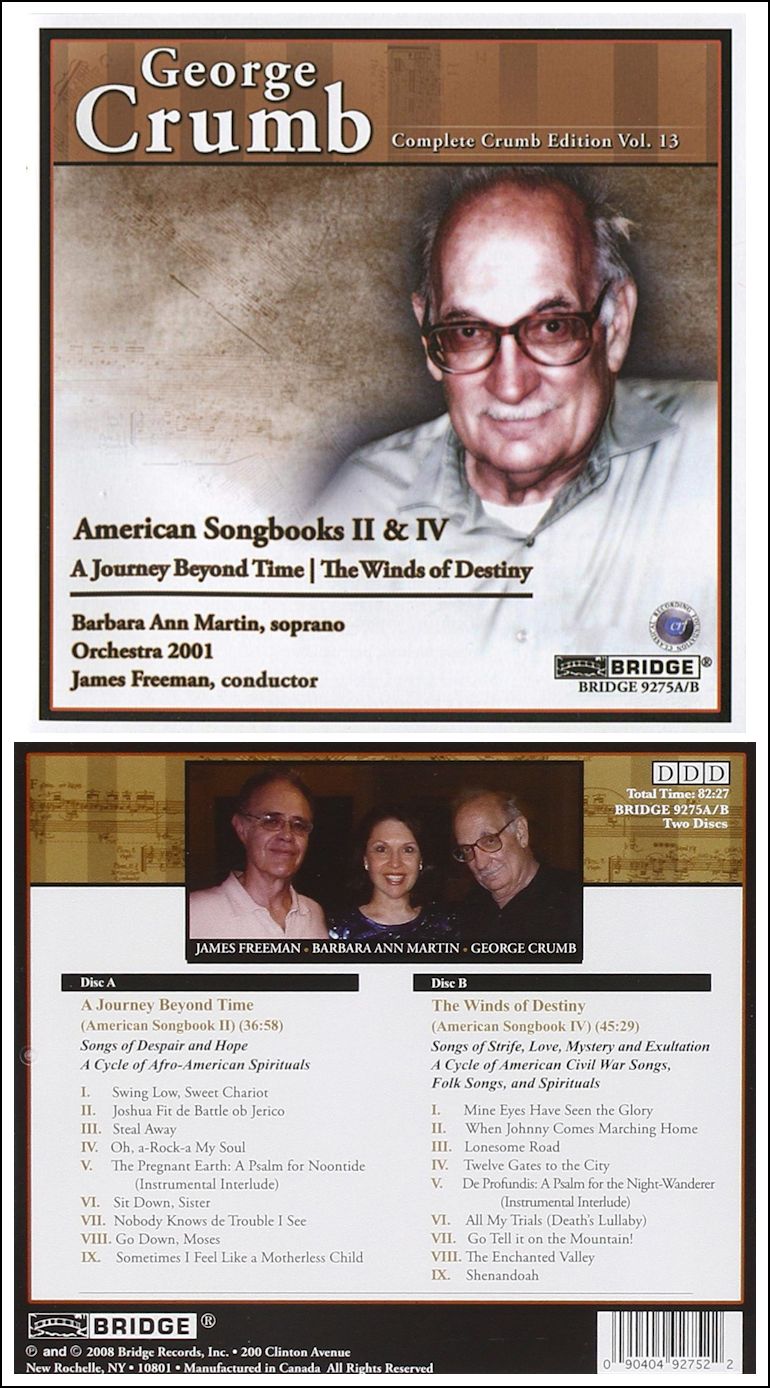

and Chinary Ung. She is also the featured soloist with James Freeman

and Orchestra 2001 on the 2010 Grammy-Nominated CD, "A Journey Beyond

Time and The Winds of Destiny" [shown below].

Martin has also been a guest professor and Artist-in-Residence

at the International Summer Academy Mozarteum in Salzburg and the Royal

Danish and Odense Conservatories in Denmark. She has served on the

faculties of Bennington College, CUNY at Brooklyn and is currently Voice

Department Chair at the Music Institute of Chicago. As an audio book

narrator, her work is featured on Amazon.com, and Audible.com. She is

also a member of NARAS (Grammys), and is an active member of SAG/AFTRA,

serving on the Singers and Audio Book Committees in Chicago. == Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

Martin: No, I don’t.

Martin: No, I don’t. BD: That’s a lot for a new piece.

BD: That’s a lot for a new piece. BD: He probably didn’t know, earlier.

Maybe it was spontaneous.

BD: He probably didn’t know, earlier.

Maybe it was spontaneous. Martin: [Thinks a moment] There are many things

in our world that seek to smother the human spirit, that seek to diminish

us. These include political ideologies, and people who do things

in the name of whatever religion they espouse. People from many walks

of life and many economic backgrounds want to diminish what we have to

offer as human beings. Music is one of the highest forces we have

to elevate the human spirit. For me, it is one of the voices of

God. It is something that vibrates through all nature, through everything

that lives, and everything that is inanimate. Everything relates

to vibrations of sound, of energy, and it’s my purpose to be as truthful

and as honest as I can to give birth to that music as it passes through

me. For me, music is our future as well as our past. Right now,

we really need the joy and the beauty and the laughter and the love that

music gives us.

Martin: [Thinks a moment] There are many things

in our world that seek to smother the human spirit, that seek to diminish

us. These include political ideologies, and people who do things

in the name of whatever religion they espouse. People from many walks

of life and many economic backgrounds want to diminish what we have to

offer as human beings. Music is one of the highest forces we have

to elevate the human spirit. For me, it is one of the voices of

God. It is something that vibrates through all nature, through everything

that lives, and everything that is inanimate. Everything relates

to vibrations of sound, of energy, and it’s my purpose to be as truthful

and as honest as I can to give birth to that music as it passes through

me. For me, music is our future as well as our past. Right now,

we really need the joy and the beauty and the laughter and the love that

music gives us.

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 22, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two days later, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.