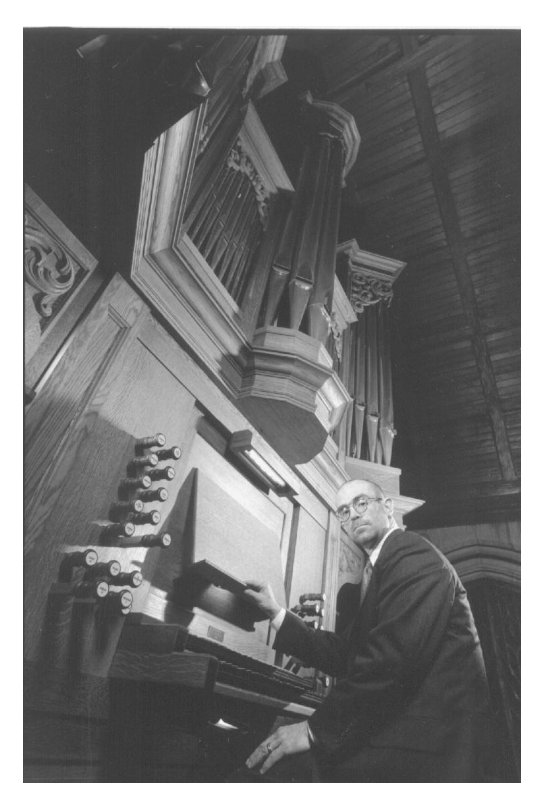

DS: Oh, sure! There are some organs, either

by nature of their size or their construction, that will have mechanical actions

that are very, very heavy. In the case of a very large mechanical action

instrument, as Hans Steketee, who was the head of Flentrop once said, “The

action can’t be like a harpsichord if the instrument is this big.” I

think, to an extent, he’s right. There’s a gravity inherent in the sound

quality of a very large organ. You want to be careful —

by your tempo and by the very way the instrument feels

— to play so that you know you’re governing it the right way.

You send these messages, as it were, from this most public of instruments

down to the audience. So the action of the instrument, if it’s really

well-built, will in some ways determine the character; or may not determine

it, rather, but reflect it.

DS: Oh, sure! There are some organs, either

by nature of their size or their construction, that will have mechanical actions

that are very, very heavy. In the case of a very large mechanical action

instrument, as Hans Steketee, who was the head of Flentrop once said, “The

action can’t be like a harpsichord if the instrument is this big.” I

think, to an extent, he’s right. There’s a gravity inherent in the sound

quality of a very large organ. You want to be careful —

by your tempo and by the very way the instrument feels

— to play so that you know you’re governing it the right way.

You send these messages, as it were, from this most public of instruments

down to the audience. So the action of the instrument, if it’s really

well-built, will in some ways determine the character; or may not determine

it, rather, but reflect it. DS: That’s a good question! [Both laugh]

I don’t know. I can say that it seems to fulfill an artistic need that painting

and sculpture and architecture and theater don’t tend to do by themselves.

What it is, is hard to explain. A friend of mine who is a wonderful

piano technician and composer says, “Do you realize that we spend our entire

lives either regulating how, or doing it ourselves, the act of people wiggling

the air?” Our profession depends on how we wiggle the air. [Both

laugh] Now what effect does that have on the listeners? It sort

of has everything. It has excitement, tenderness, bravado, pathos, all

the different things you could go through. So what is the purpose of

music? I’m not sure.

DS: That’s a good question! [Both laugh]

I don’t know. I can say that it seems to fulfill an artistic need that painting

and sculpture and architecture and theater don’t tend to do by themselves.

What it is, is hard to explain. A friend of mine who is a wonderful

piano technician and composer says, “Do you realize that we spend our entire

lives either regulating how, or doing it ourselves, the act of people wiggling

the air?” Our profession depends on how we wiggle the air. [Both

laugh] Now what effect does that have on the listeners? It sort

of has everything. It has excitement, tenderness, bravado, pathos, all

the different things you could go through. So what is the purpose of

music? I’m not sure. DS: Oh, absolutely. He was at St. James Cathedral

for a while. We will also do his E

Flat Major Sonata in Four Movements that ends with a fugue on Hail, Columbia. It’s really a good

piece. There will also be a piece by Wilhelm Middelschulte, who used

to be at Holy Name Cathedral, and Eric DeLamarter, who was one of Morgan Simmons’

predecessors at Fourth Presbyterian.

DS: Oh, absolutely. He was at St. James Cathedral

for a while. We will also do his E

Flat Major Sonata in Four Movements that ends with a fugue on Hail, Columbia. It’s really a good

piece. There will also be a piece by Wilhelm Middelschulte, who used

to be at Holy Name Cathedral, and Eric DeLamarter, who was one of Morgan Simmons’

predecessors at Fourth Presbyterian. DS: Oh, not at all! In fact at this point,

we now go to great lengths to have organs built so that wind can be raised

by hand or by foot, and that also motors for such instruments are built painstakingly,

with the idea that you’d be able to engineer the same effect with electricity

in case you don’t have a calcant — you know, a bellows man. When I played

at Wellesley, I had human winding. It’s not unsteady at all. It’s

no more unsteady than the supplying of the wind by electricity, if the bellows

person knows what he or she is doing. I had a very lithe German girl,

and with one bellows being worked from above and the other from the feet,

it made a constant, very slow-motion aerobic exercise on the part of the

bellows person. Of course, you invited your bellows person out at the

end to take a bow with you, because the soul of your performance really came

from that person. If she decided to stop, that’s the end of the program.

[Both laugh] It’s all by way of saying that the older music

— from the very early part of the 19th century and before — is

predicated on the idea that the wind wouldn’t be steady, so you would be

able to do many more intimate things of control with the wind. When

organ music became more dominated by piano technique, the idea of sharp attacks

and continuous legato predicated a different kind of winding system.

DS: Oh, not at all! In fact at this point,

we now go to great lengths to have organs built so that wind can be raised

by hand or by foot, and that also motors for such instruments are built painstakingly,

with the idea that you’d be able to engineer the same effect with electricity

in case you don’t have a calcant — you know, a bellows man. When I played

at Wellesley, I had human winding. It’s not unsteady at all. It’s

no more unsteady than the supplying of the wind by electricity, if the bellows

person knows what he or she is doing. I had a very lithe German girl,

and with one bellows being worked from above and the other from the feet,

it made a constant, very slow-motion aerobic exercise on the part of the

bellows person. Of course, you invited your bellows person out at the

end to take a bow with you, because the soul of your performance really came

from that person. If she decided to stop, that’s the end of the program.

[Both laugh] It’s all by way of saying that the older music

— from the very early part of the 19th century and before — is

predicated on the idea that the wind wouldn’t be steady, so you would be

able to do many more intimate things of control with the wind. When

organ music became more dominated by piano technique, the idea of sharp attacks

and continuous legato predicated a different kind of winding system. BD: In chamber music, you have to listen more than

feel. When you’re playing alone you can feel and listen.

BD: In chamber music, you have to listen more than

feel. When you’re playing alone you can feel and listen. DS: Sometimes, yes, I think you’re shooting for

something different. You’re certainly shooting for a personal interpretation,

but in some ways what you do in a recording studio, while spontaneous to an

extent, is more calculated. You want to make sure that you play cleanly,

in a way that you know is going to last innumerable playings —

as the old vinyl records used to say they would. In a live

performance, you might want to do something eccentric that you think will

rub off well on your audience, but not in a recording studio.

DS: Sometimes, yes, I think you’re shooting for

something different. You’re certainly shooting for a personal interpretation,

but in some ways what you do in a recording studio, while spontaneous to an

extent, is more calculated. You want to make sure that you play cleanly,

in a way that you know is going to last innumerable playings —

as the old vinyl records used to say they would. In a live

performance, you might want to do something eccentric that you think will

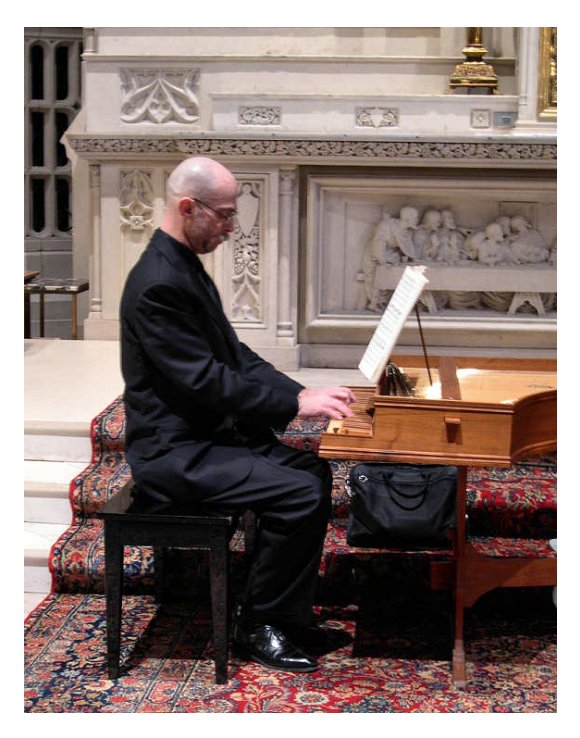

rub off well on your audience, but not in a recording studio.| David Schrader (Harpsichord, Organ) Born: September 15, 1952 - Chicago, Illinois, USA The American organist, harpsichordist and fortepianist, David Dillon Schrader, received a Bachelor of Music in piano and a Bachelor of Music in organ with Spoecial Honours from the University of Colorado in 1974. He received Performer's Certificate in 1974, Master of Music with High Distinction in 1975, and Doctor of Music degree in organ in 1987 from Indiana University. His principal teachers have been Storm Bull, Abbey Simon, Oswald Ragatz, Anthony Newman and Everett Jay Hilty. Equally at home in front of a harpsichord, organ, piano, or fortepiano, David Schrader is "truly an extraordinary musician ... (who) brings not only the unfailing right technical approach to each of these different instruments, but always an imaginative, fascinating musicality to all of them" (Norman Pelligrini, WFMT, Chicago). A performer of wide ranging interests and accomplishments, he has been invited to perform at the American Guild of Organists’ national convention on three occasions performing as a featured artist with the Dallas Symphony Orchestra (1994), the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra (under Neeme Järvi, 1984), and the Colorado Symphony Orchestra (1998). He has appeared as a soloist on organ and on harpsichord with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra having performed under the direction of Sir Georg Solti, Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez and Erich Leinsdorf. He has also appeared with the Grant Park Symphony under Carlos Kalmar, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, El Paso Symphony Orchestra, and with many other orchestras throughout the USA and Canada. David Schrader has appeared at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as the repetiteur and principal harpsichordist in Chicago Opera Theater’s highly acclaimed production of Orfeo under Jane Glover. In May 2002 he performed five concerts as the featured performer at the prestigious Irving Gilmore Keyboard Festival, performing concerts on organ, harpsichord and clavichord. And, in the summer of 2002 he appeared as a soloist at the Ravina Festival under the direction of Nicholas McGegan performing all six of the J.S. Bach’s Brandenberg Concertos. David Schrader has appeared at numerous music festivals throughout the USA and Europe. At the prestigious Irving Gilmore Keyboard Festival, he was the featured performer performing five separate concerts, performing on organ, harpsichord and clavichord. He performed as the Artist of the Year at the Oulunsalo Soi Music Festival in Oulu, Finland. In 2000 he was the harpsichord soloist with the Nagaokakyo Chamber Ensemble in a tour of Japan under Yuko Mori and the Canadian Baroque orchestra Tafelmusik in a European tour, He has also performed at the Aspen Music Festival, the Michigan Mozartfest with Roger Norrington, the Connecticut Early Music Festival, the Manitou Music Festival, and the Woodstock Mozart Festival where he performed as soloist and conductor. A resident of Chicago, David Schrader leads an active musical life at home. For 20 years, he has been the organist of the Church of the Ascension, whose liturgies command a national reputation for musical integrity. He performs with Music of the Baroque, the Newberry Consort, and Bach Week Festival in Evanston. He has appeared with Chicago Chamber Musicians, Contemporary Chamber Players, Chicago Baroque Ensemble, and The City Musick. He has taken part in numerous live and recorded radio broadcasts, nationally distributed. He is a frequent guest on WFMT radio (Chicago) on recordings and in live broadcasts as part of WFMT's "Live From Studio One" programming. David Schrader's newest recording with Grant Park Symphony of music for organ and orchestra by American composers is the first recording of the Casavant Frères organ in Chicago's Symphony Center which was described by John von Rhein of the Chicago Tribune as a "rich palette of sounds and deft rhythmic interplay ...Schrader's 17th recording for the Chicago-based indie label may be his best yet. Go for it." His other recordings include concerti of J.S. Bach with the Stuttgarter Kammerorchester, and continuo with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra for both recordings of Sir Georg Solti's Creation, and the St. Matthew Passion (BWV 244) and Messiah. He has many releases of solo repertoire on the Cedille label, including the music of J.S. Bach, Soler, Franck, Antonio Vivaldi, Dupré and Domenico Scarlatti. His recording of Soler’s "Fandango & Sonatas" was described thus "We have never heard more beautiful, natural, realistic harpsichord sound .. The playing? Excellent ... There is no better recording on CD" (American Record Guide). "The popular ‘Fandango’ has perhaps never received so exhilarating a reading" (Chicago Tribune). "His recording of J.S. Bach "Fantasies & Fugues" "captures the sense of improvisatory, virtuosic energy that is to be found so plentifully in this music." (Continuo) He has also recorded for the Centaur and CRI labels. David Schrader is on the faculty of Roosevelt University, Chicago College of Performing Arts - Music Conservatory for performance and academic studies where he has taught both graduate and undergraduate courses since 1986. From 1993 through 1995 he directed the Collegium Musicum at Northwestern University. He has also taught at the Music Institute of Chicago (formerly known as The Music Center of the North Shore.) |

This interview was recorded at the studios of WNIB, Chicago, on August 9, 1992. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB a few weeks later, and again in 1997. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.