|

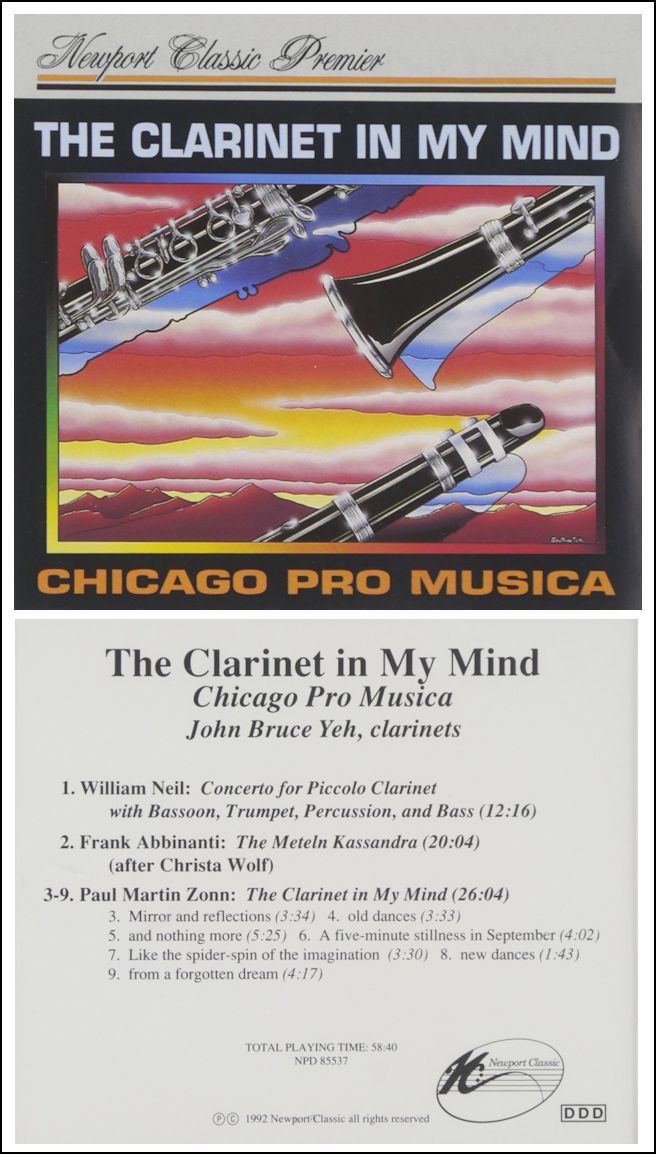

The music of William

(Grosvenor) Neil (FAAR ’83) has been performed on both

sides of the Atlantic and has been featured at the Festival of Music

in Evian, France, the Electronic Plus Festival in New York, the Pontino

Festival in Italy, and the New Music Chicago Festival. He has written

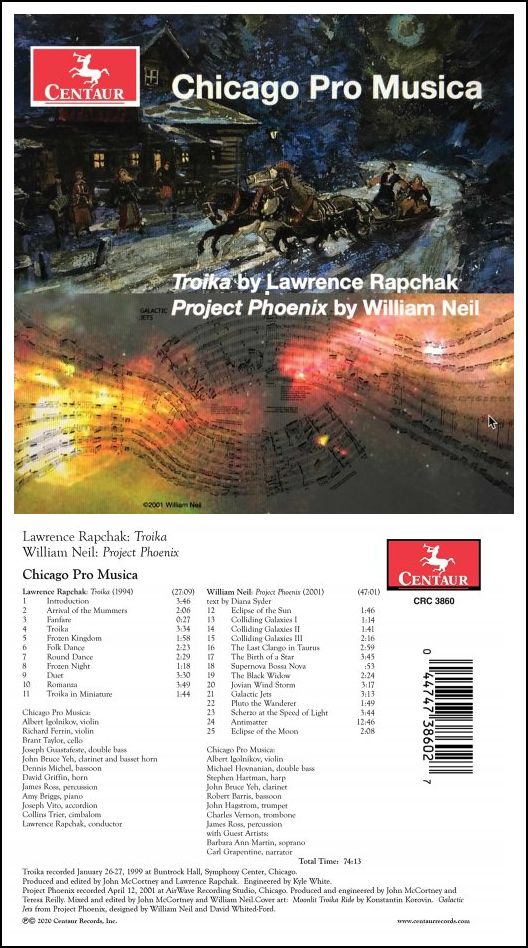

works for celebrated musicians including Concerto for Piccolo Clarinet

for John Bruce Yeh

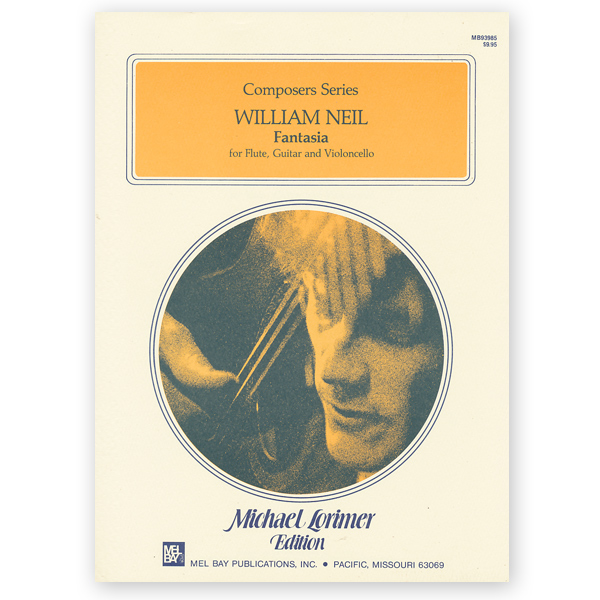

and Chicago Pro Musica, recorded on the Newport Classic label, Fantasia

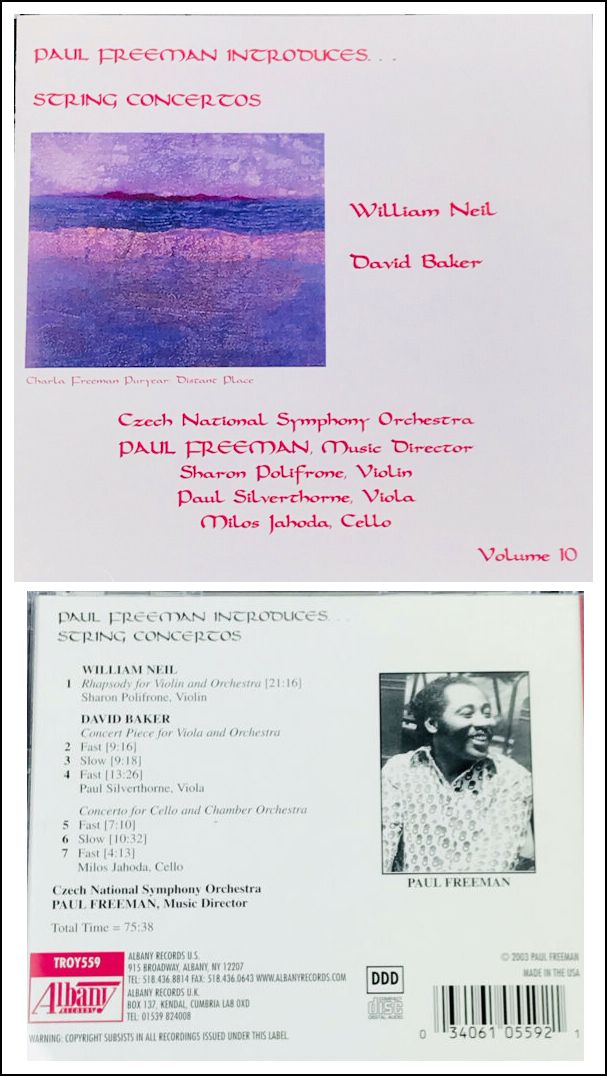

for guitarist Michael Lorimer, published by Melbay, Violin Rhapsody

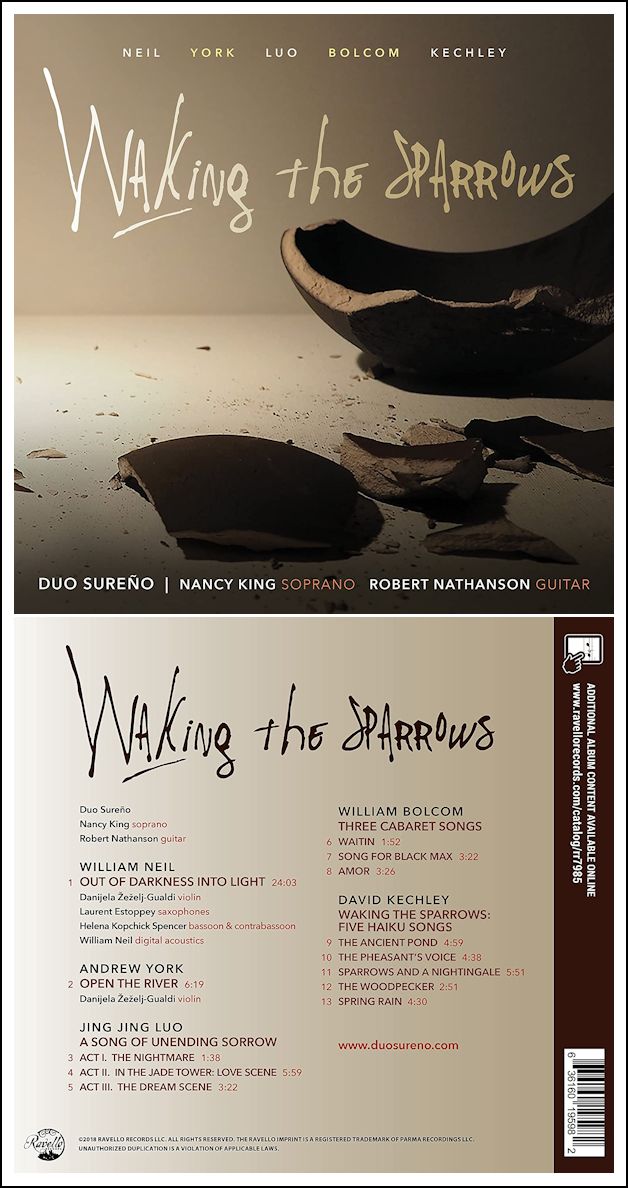

for violinist Sharon Polifrone recorded on Albany Records, At the

Edge of the Body’s Night for Duo Sureno recorded on the Liscio

Label, Out of Darkness Into Light for Pro Musica recored

on the Ravello Recordings, Spiritual Adaptation to Higher Altitudes

for clarinetist Corey Mackey, recorded on the Mark Masters Label, and

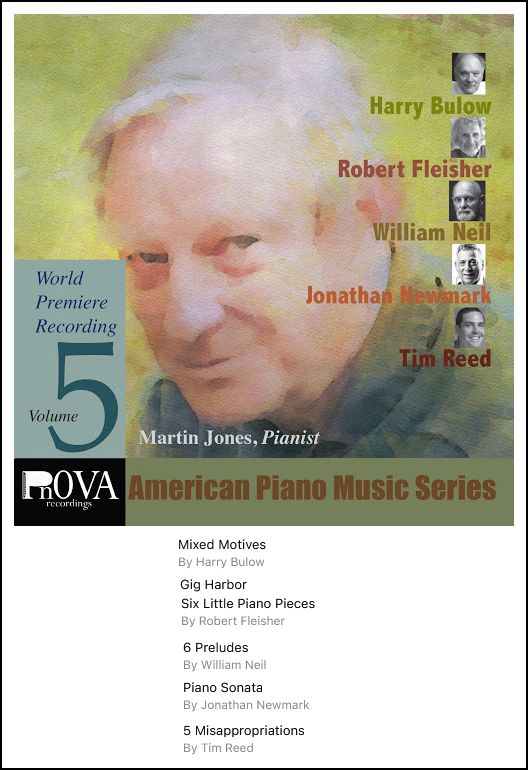

Six Preludes for pianist Martin Jones recorded on PnOVA Recordings.

His songs set to poems by D.H.Lawrence, The Waters Are Shaking

the Moon, for soprano Barbara Ann Martin,

were premiered on WFMT radio in June of 1996.

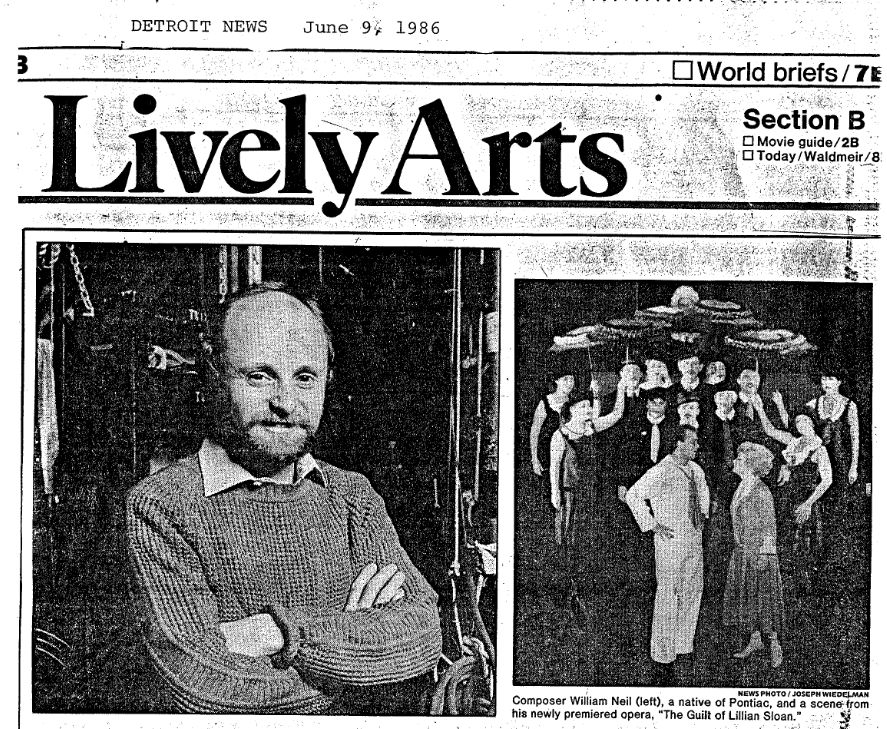

In 1984 he was appointed the first composer-in-residence with the Lyric Opera of Chicago. His first opera, The Guilt of Lillian Sloan, was premiered in 1986. His orchestral works have been performed by the Grant Park Symphony Orchestra, The Chicago Chamber Orchestra, the Opus One Chamber Orchestra, Concertante di Chicago and the Czech National Symphony. Commissioned works include, The Waters Are Shaking the Moon, Rhapsody for Violin for Concertante di Chicago, Scherzo at the Speed of Light for Northern Kentucky University, Project Phoenix for Chicago Pro Musica, and Super String Quartet for the Arts Association of Denmark, At the Edge of the Body’s Night for Duo Sureno, Out of Darkness Into Light for Pro Musica, and Sinfonia delle Gioie for the La Crosse Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Alexander Platt. Residencies and Significant Performances In 2007 Neil served as a McKnight Foundation Visiting Composer-in-residence for city of Winona, MN where his Oratoria for chorus and soloists was premiered by the St. Mary’s University Chamber Choir. In September of 2012 he was in residence at the D.H. Lawrence Gargnano Centenary Symposium in Gargnano, Italy, performing his song cycle The Waters Are Shaking the Moon and a commissioned work, Where There is No Autumn. The following year, Trio Malipiero premiered his piano trio, Notte dei Cristalli, at the Teatro alla Specola in Padova. Recent commissions include, Out of Darkness Into Light and Love Poem with a Knife for Duo Sureno and Pro Musica premiered at the Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, NC. Italian pianist, Giacomo dalla Libera premiered Nocturne No. 1, Prelude No. 3, and Tango No. 2 at Morely College in London in 2018. In the spring of 2020, Neil served as an Artist-in-Residence at Badlands National Park. Sound Design & Radio Production Neil is the artistic director of TheComposerStudio.Com, LLC that specializes in film and sound design for theatre. Recently, he has produced sound design for the In Tandem Theatre Company production of Beast on the Moon and The Glass Menagerie in Milwaukee, WI. He has also worked with the actor-director Phil Addis in designing sound for Nosferatu for the Viroqua Community Theatre. Recent film scores include the Community Conservation documentary Conservation of the Yellow Tailed Wooly Monkey. Neil regularly co-hosts Symphony Sunday on WDRT in Viroqua, WI, a three-hour classical music program that features interviews with local musicians and live music. He is currently producing a ten-episode program featuring interviews with the American composer, George Crumb about his American Songbook series of recordings. Performance He also actively performs with Project FourthStream as pianist, composer with jazz musicians Tom Gullion and Karyn Quinn. The group has recorded and produced two recordings: This Music in 2010, followed by Out of Darkness Into Light in 2017. In June of 2016 he performed a solo piano recital of his own piano music, Verde, Bianca, Rosa Concerto at the Academia della Musica in Sofia d’Epiro in Calabria Italy. Education Neil earned the Bachelor and Masters Degrees in Composition from the Cleveland Institute of Music & Case Western Reserve University where he studied with composer Donald Erb. He pursued advanced musical studies with Joachim Blüme at the Staatliche Hochschule fur Musik, Koln, Germany and holds the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree in Composition from the University of Michigan School of Music, studying composition with Leslie Bassett, William Bolcom, Eugene Kurtz, and William Albright. Awards His creativity has been recognized

by awards from the McKnight Foundation (2008), the American Academy

of Arts and Letters (1982), a BMI composition award (1981), an ASCAP

award (1981), a Fulbright Fellowship (1978-1979), commissions from the

National Endowment for the Arts (1978, 1984), an Illinois Arts Grant

(1988), and the Rome Prize from the American Academy in Rome (1983).

In 1988 he received the Armstrong Award for jointly producing Music

at Hight Noon along with WFMT host Kerry Frumkin as part of the 1988

New Music Chicago Spring Festival. Neil was also awarded a 2008

Visiting Composer’s grant from the McKnight Foundation for the city of

Winona, MN. == Biography

from the composer’s website

(with slight corrections) |

Bruce Duffie: When

did you decide to become a composer?

Bruce Duffie: When

did you decide to become a composer? BD: Just a little post-Debussy?

BD: Just a little post-Debussy? BD: But you can understand their techniques.

BD: But you can understand their techniques.

BD: Is this to say that chamber groups have lost

their composer now?

BD: Is this to say that chamber groups have lost

their composer now? BD: Are you tainted, now, being

an opera composer? Would you be accepted on Broadway?

BD: Are you tainted, now, being

an opera composer? Would you be accepted on Broadway? Neil: Musical techniques I can always

speak about. Production techniques are something you can get

involved later on in your career. If you’re able to be a powerful

musical figure, you can start moving your way around and say you want

this or that. For example, Philip Glass has that

option open to him now. Wagner did it to an hysterical extreme.

Think of it, a festival devoted just to his music, and a theater designed

just for his music! [Both laugh] It’s only when the ego is able

to grow with considerable funding beneath it that they can occur, so I

don’t consider myself with that. I like the idea of having a work

done, and letting people get excited about it. Let them evolve

their talents, and not impose my ego on them. So musically speaking,

yes, I’m eager to try out new techniques, and also those I have seen being

tried in recent times, as well as those techniques of the past.

There’s a tremendous supply of techniques that Verdi used, or even Monteverdi

used in his operas, as well as those of Lully and Mozart that can be employed.

Techniques are such that you have to file them away, or use a computer

to keep them in store. There are so many techniques, and they all

must serve the poetry of the drama and the music. They’re not just

to be laid up there for their own display. They are techniques that

serve the ultimate spectacle.

Neil: Musical techniques I can always

speak about. Production techniques are something you can get

involved later on in your career. If you’re able to be a powerful

musical figure, you can start moving your way around and say you want

this or that. For example, Philip Glass has that

option open to him now. Wagner did it to an hysterical extreme.

Think of it, a festival devoted just to his music, and a theater designed

just for his music! [Both laugh] It’s only when the ego is able

to grow with considerable funding beneath it that they can occur, so I

don’t consider myself with that. I like the idea of having a work

done, and letting people get excited about it. Let them evolve

their talents, and not impose my ego on them. So musically speaking,

yes, I’m eager to try out new techniques, and also those I have seen being

tried in recent times, as well as those techniques of the past.

There’s a tremendous supply of techniques that Verdi used, or even Monteverdi

used in his operas, as well as those of Lully and Mozart that can be employed.

Techniques are such that you have to file them away, or use a computer

to keep them in store. There are so many techniques, and they all

must serve the poetry of the drama and the music. They’re not just

to be laid up there for their own display. They are techniques that

serve the ultimate spectacle. BD: Does opera belong on television?

BD: Does opera belong on television?© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in William Neil’s studio in the Opera House in Chicago on June 28, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1988, 1989, 1994, and 1999. This transcription was made in 2020, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.