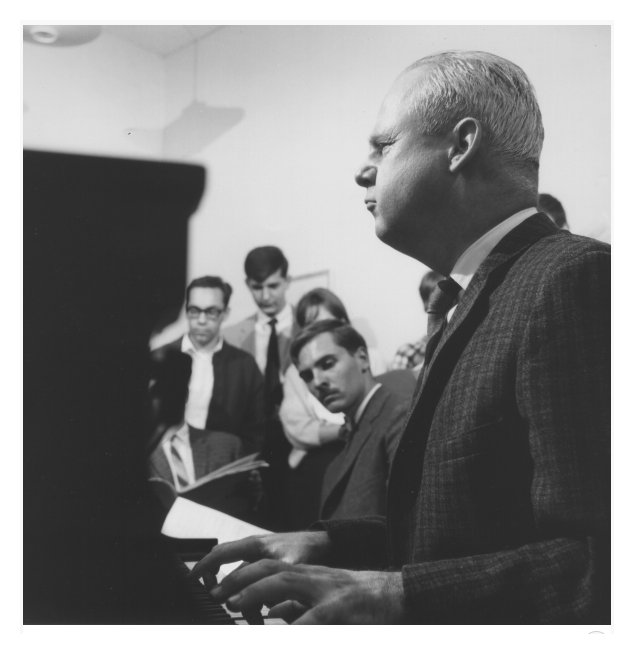

| Born in Syracuse, New York on June

2, 1915, Robert Moffat Palmer began piano studies with his mother at age 12.

He attended Syracuse's Central High School, undertaking pre-college studies

in piano and additional study of violin and music theory at the Syracuse Music

School Settlement. Awarded a piano scholarship to the Eastman School of Music,

he soon became a composition major. At Eastman, he studied with Howard Hanson

and Bernard Rogers, earning bachelor's (1938) and master's (1940) degrees

in composition. He undertook additional studies with Quincy Porter, Roy Harris

and, at the first composition class at the Tanglewood Music Center in 1940,

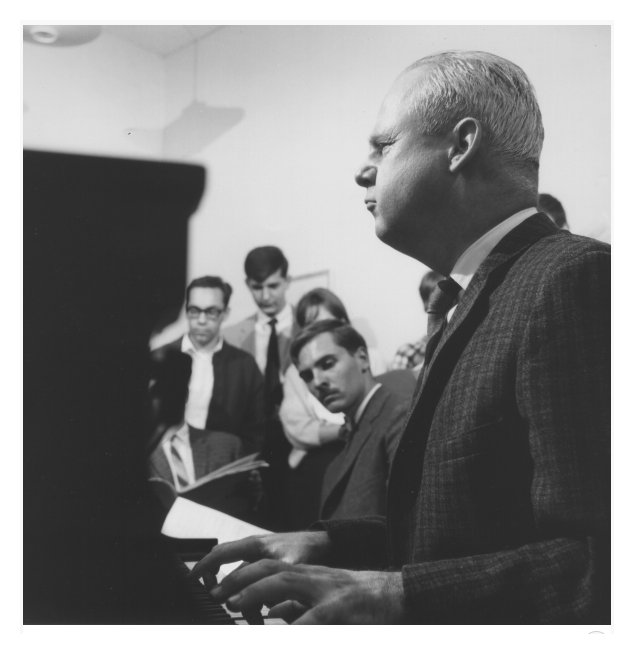

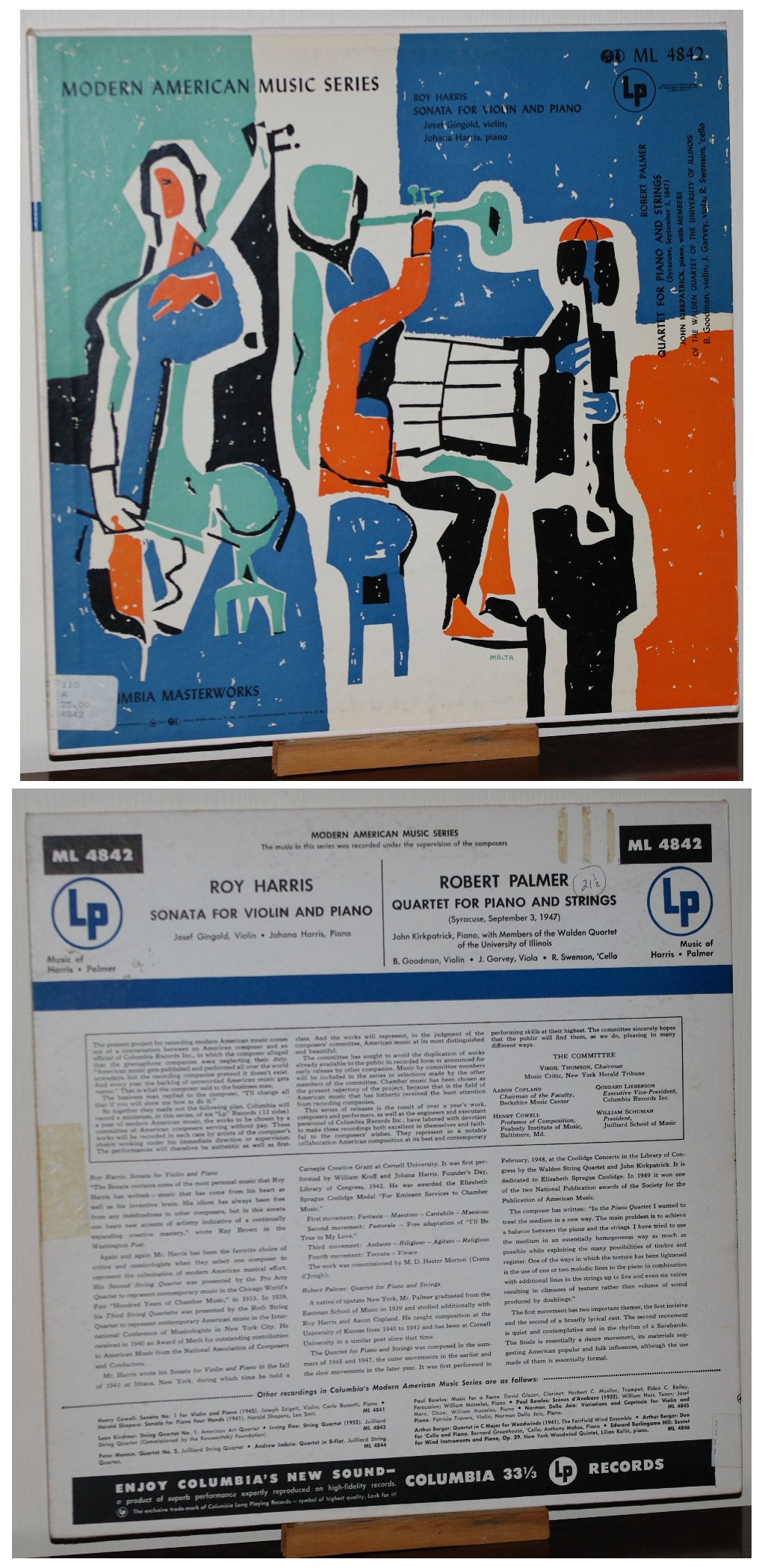

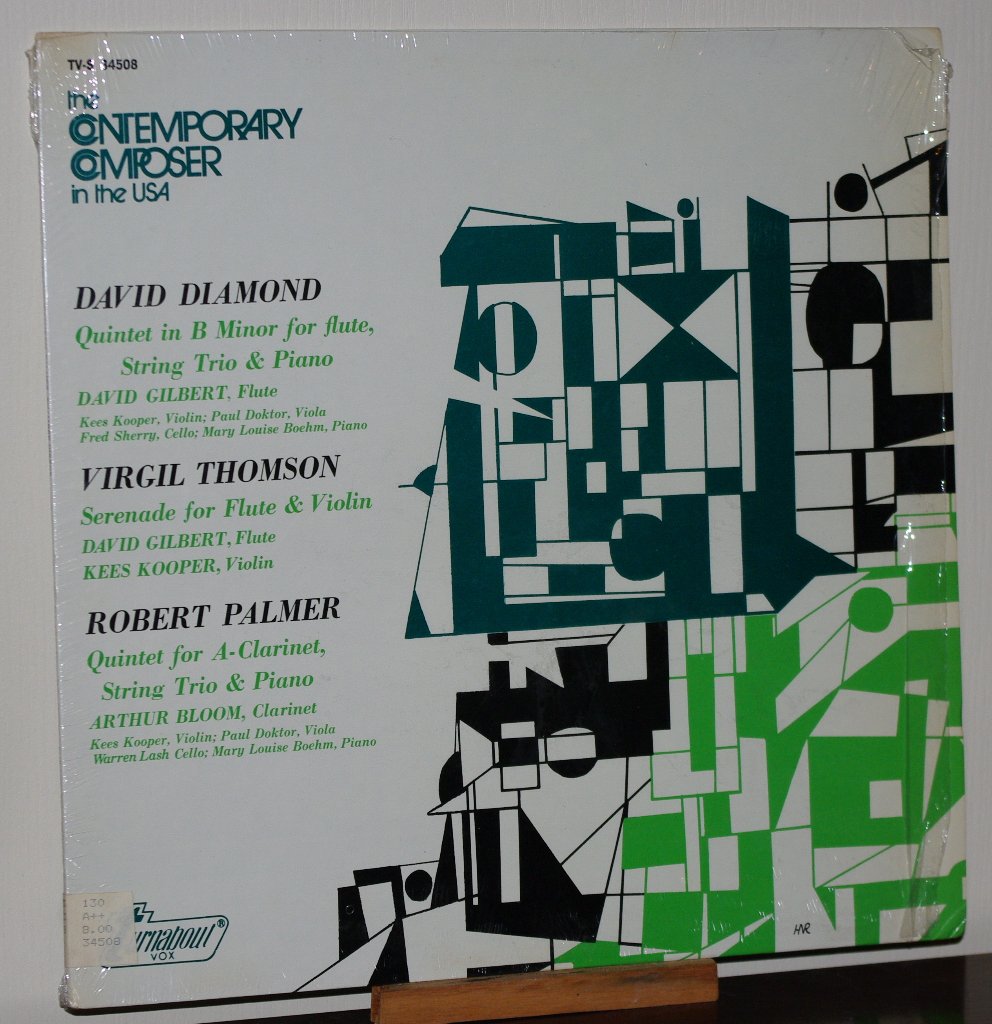

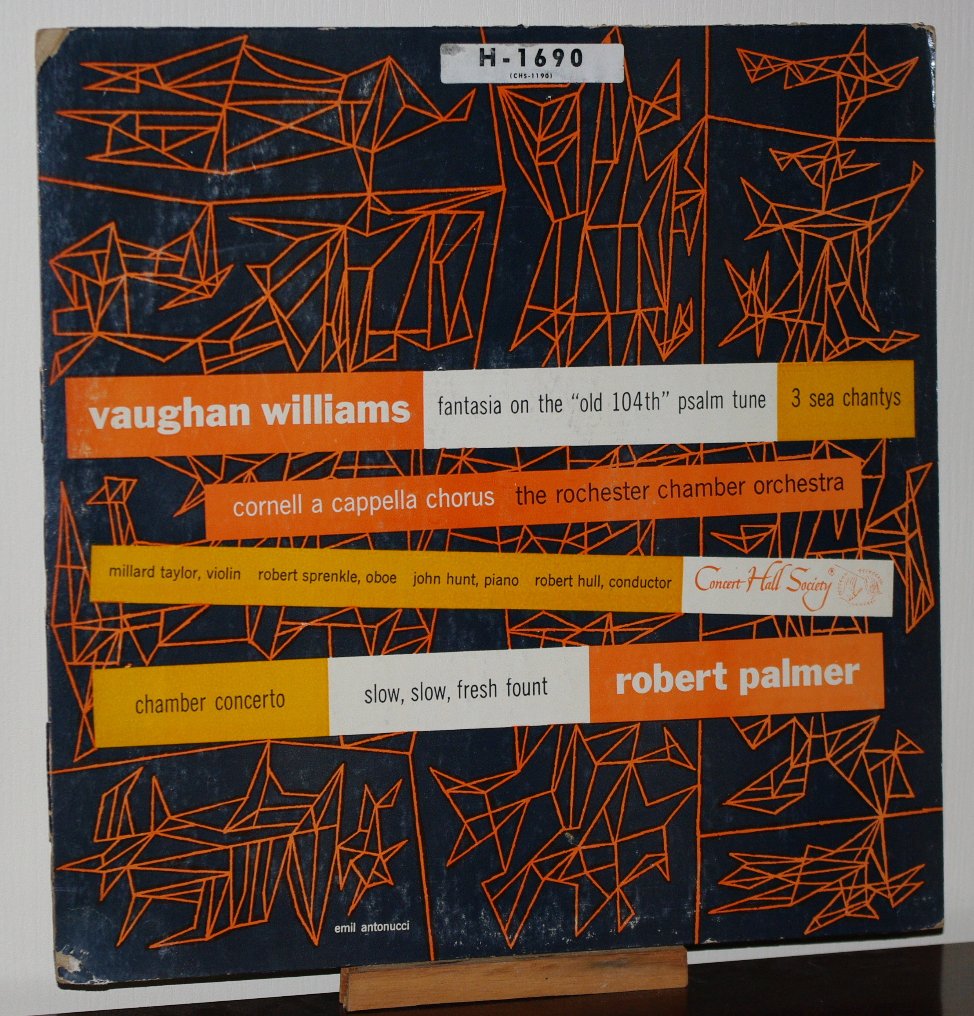

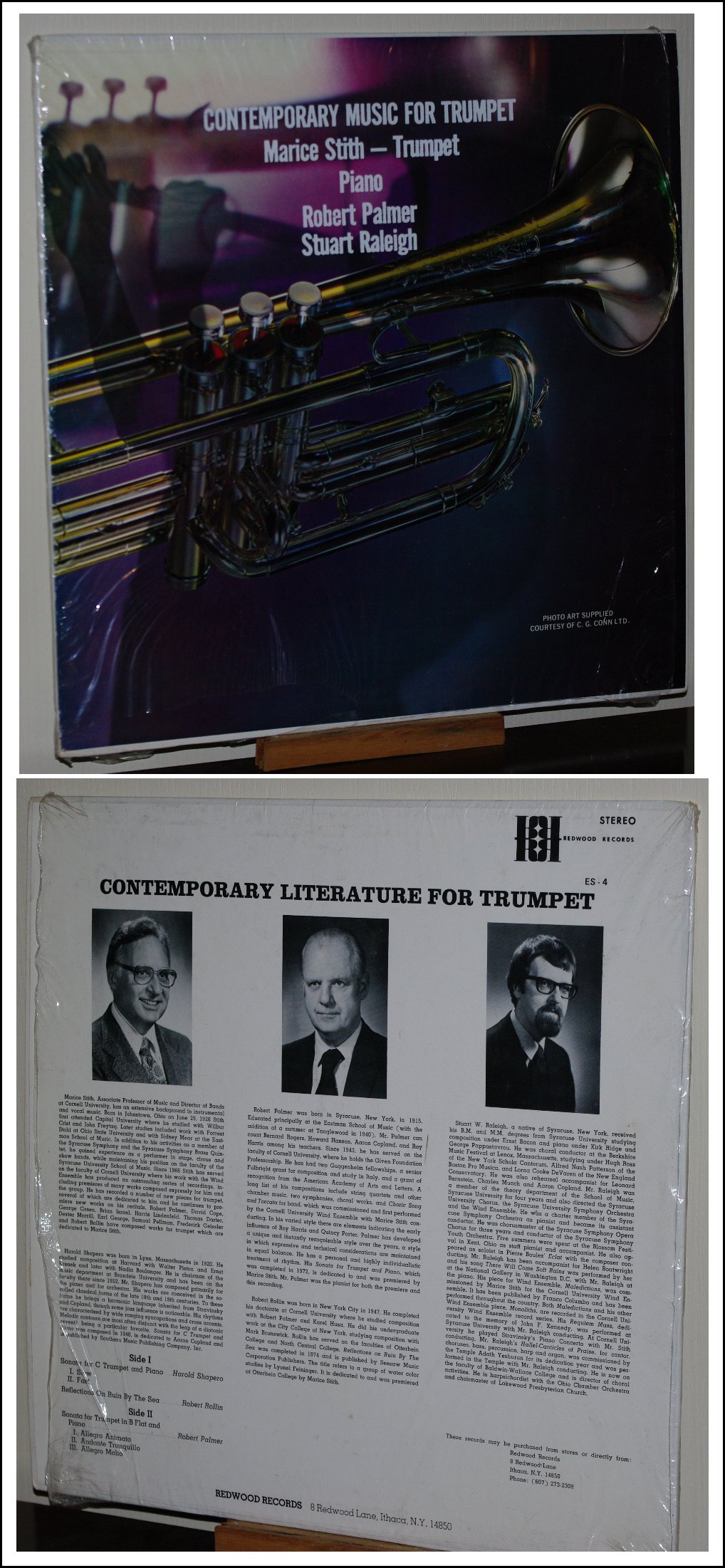

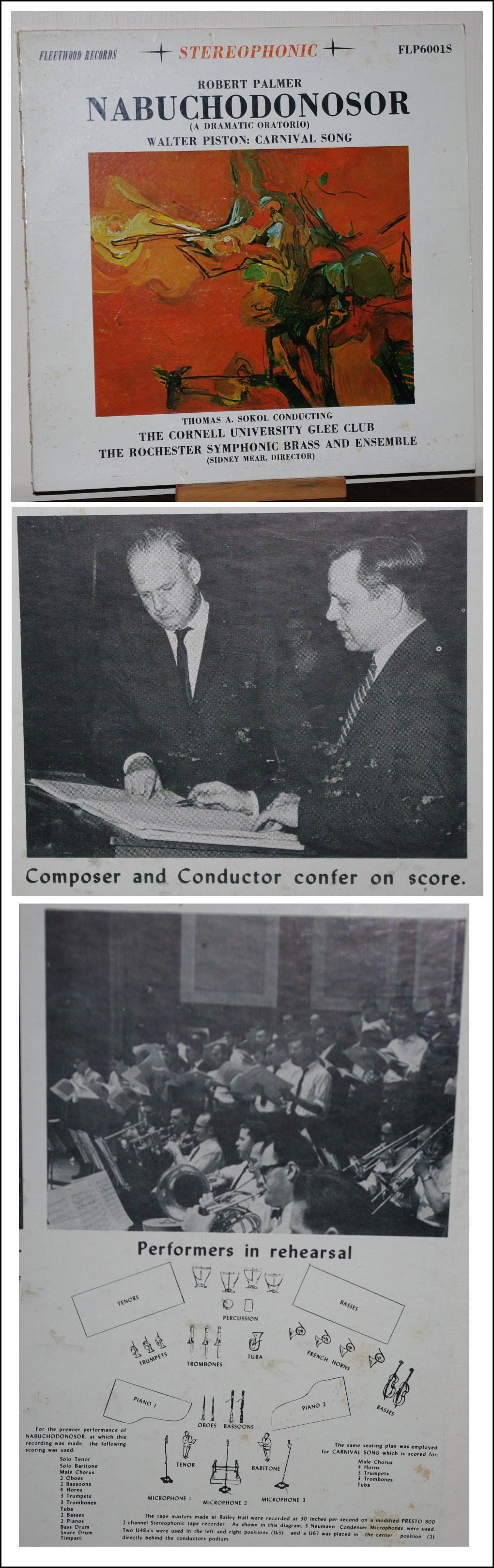

with Aaron Copland. Palmer came to national attention in an article titled "Robert Palmer and Charles Mills" published in 1943 by critic Paul Rosenfeld in Modern Music. Rosenfeld hails two "new, impressive, distinctive works" by Palmer," noting "an impression of robustness and maturity." In the Concerto for Small Orchestra (1940), Rosenfeld discerns a "quite original opening movement, (whose) clash of melodies in contrary motion was magnificent and fierce," signaling "a new composer to be watched with happy expectation." Further national attention came with the publication in 1948 by Aaron Copland of an article in The New York Times titled "The New 'School' of American Composers." Copland's article singles out Palmer as one of seven composers "representative of some of the best we have to offer the new generation," adding that "Palmer happens to be one of my own particular enthusiasms." [The other six composers are Leonard Bernstein, Harold Shapero, Alexei Haieff, John Cage, Lukas Foss, and William Bergsma.] In Palmer's first two string quartets, Copland discerns "separate movements of true originality and depth of feeling," observing that "always his music has urgency—it seems to come from some inner need for expression." Early in his career, Palmer taught music theory, composition and piano at the University of Kansas from 1940 until 1943. From 1943 until his retirement in 1980, Palmer served as a member of the faculty at Cornell University, where he was appointed Given Foundation Professor of Music in 1976. According to Pulitzer Prize-winning composer Steven Stucky, Chair of the Board of Directors of the American Music Center and a former Palmer student, "(Palmer) founded the doctoral program in music composition at Cornell University, which was the first in the United States (and quite possibly the world)." Writing in Clavier magazine in 1989, pianist Ramon Salvatore observed that "[Palmer's] influence on two generations of Cornell composers has been enormous; many of his former students now hold university and college professorships throughout the United States" Additionally, Palmer served as visiting composer at Illinois Wesleyan University in 1954 and as the George A. Miller Professor of Composition at the University of Illinois in 1955-56. Many of Palmer's most distinctive works date from his Cornell period. Stucky remarks that Palmer "once seemed poised to become a leading national figure. A steady stream of first-rate pieces attracted top performers in concert and on recordings: the Second Piano Sonata (1942; 1948), championed by John Kirkpatrick; Toccata Ostinato (1945), a boogie-woogie in 13/8 written for pianist William Kapell; the First Piano Quartet (1947); the Chamber Concerto No. 1 (1949); the Quintet for Clarinet, Piano, and Strings (1952). Most influential of these was the mighty Piano Quartet, which used to loom large as one of the major accomplishments of American chamber music." [See jackets of early LP recordings of these three last-mentioned works in box below.] Echoing this assessment, Robert Evett, in a review written in 1970 for the Washington Evening Star of Palmer's First Piano Quartet, found it "one of the most engrossing works of a superb American composer. ... At its premiere, it was a triumph. It was a triumph again last night." Palmer's publishers include Elkan-Vogel, Peer International, C. F. Peters Corporation, G. Schirmer Inc., Valley Music Press, and Alphonse Leduc-Robert King, Inc. Besides Stucky, Palmer's students include Christopher Rouse (also winner of the Pulitzer Prize), Paul Chihara, Bernhard Heiden, Brian Israel, Ben Johnston, David Conte, John S. Hilliard, Leonard Lehrman, Daniel Dorff, Jerry Amaldev, and Jack Gallagher. Palmer died in Ithaca, New York on July 3, 2010. -- Note: Names which are links

refer to my interviews elsewhere on this website. BD

|

To read my Interview with Virgil Thomson, click HERE. To read my Interview with William Schuman, click HERE.

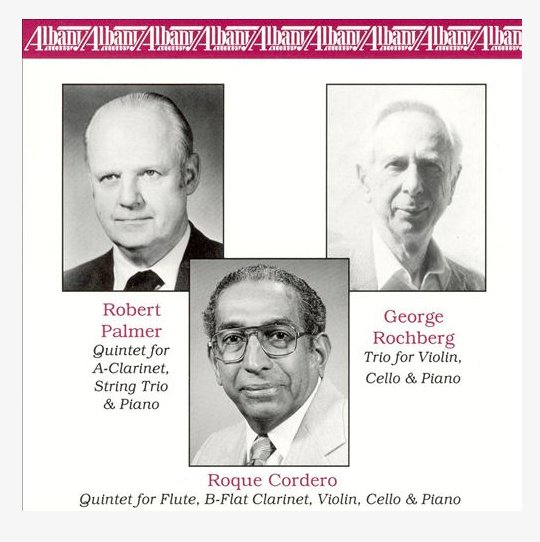

To read my Interview with David Diamond, click HERE. [The Palmer recording was later re-issued on the Albany CD shown below.]

To read my Interview with George Rochberg, click HERE. To read my Interview with Roque Cordero, click HERE.

|

RMP: I think there was a little water in the well!

[Both laugh]

RMP: I think there was a little water in the well!

[Both laugh]© 1988 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 14, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, and again in 1995 and 2000. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.