|

Kupferman was born in New York City, on July 3rd, 1926, the first child of Elias and Fanny Kupferman. The family moved around frequently when he was young. At age five he began violin lessons, but did not show any musical inclination. However, by age ten he as exposed to the clarinet, an instrument that opened the world of music to him. He took lessons, taught himself to compose and play the piano and started to compose pieces and arrangements for friends. Kupferman was primarily self-taught, although he did take classes in theory and composition at the High School of Music and Art and Queens College. In order to provide an avenue through which to perform his compositions, Kupferman founded the Composers Workshop. Several individuals who played with him in these early years, moved on to become composers in their own right. In 1951, Meyer Kupferman was offered a professorship in both composition and chamber music at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY. He taught there for 43 years and retired in 1993. During his time at the College, Kupferman conducted the orchestra and chorus, taught classes in music theory, and founded the Sarah Lawrence Improvisation Ensemble. Kupferman received grants from the Guggenheim Fellowship, National Endowment for the Arts, and the Ford Foundation. He also received composition awards from the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters and ASCAP. He had one daughter, Lisa Pitt, from his first marriage. He subsequently married Pei Fen Chin in 1973, and was also father to three stepsons: Fung Chin, Sung Chin and Yun Chin. Meyer Kupferman died on November 26, 2003, in Rhinebeck, New York. -- Biography from the Archives & Manuscripts

section of the New York Public Library (with correction)

* * *

* *

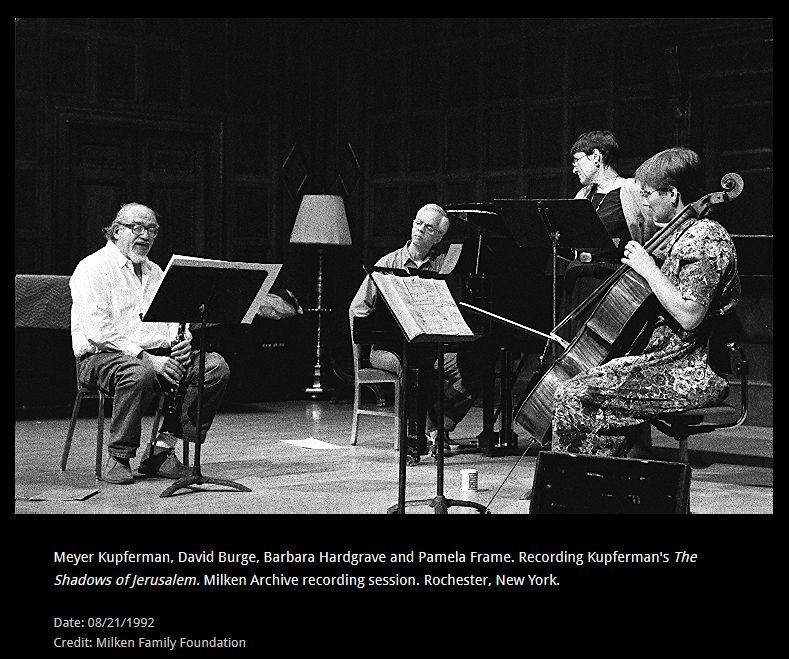

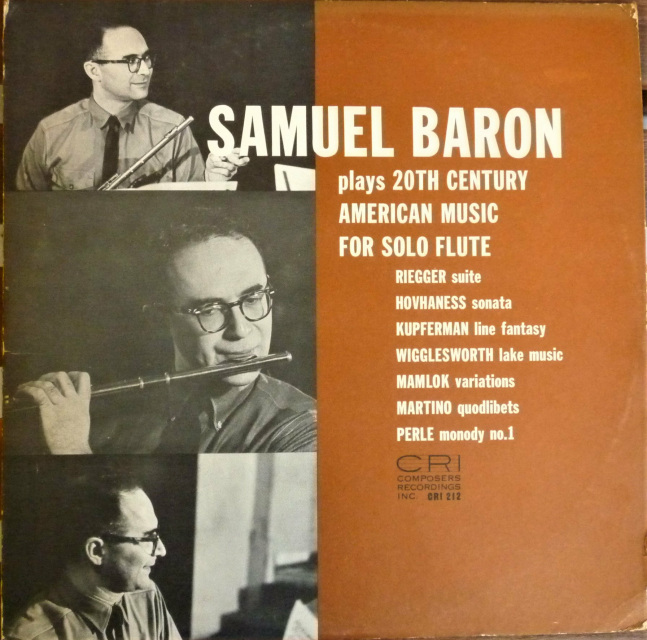

Kupferman (with beard) is shown on the left in this photo from the CRI CD booklet. See my interview with Richard Wilson. |

BD: Are there ever times when they accomplish everything?

BD: Are there ever times when they accomplish everything? MK: That’s a hard question to answer. I had a small

tape machine there, and I interviewed a number of instrumentalists, and

the conductor, to hear what their views were about the current political

situation. Everyone talked quite freely, except one person who

I suspect may have been a little too pro-Russian and maybe a KGB agent.

She was very guarded, but the others were openly saying they were looking

forward freedom and to new regime that would make life a little easier

for them.

MK: That’s a hard question to answer. I had a small

tape machine there, and I interviewed a number of instrumentalists, and

the conductor, to hear what their views were about the current political

situation. Everyone talked quite freely, except one person who

I suspect may have been a little too pro-Russian and maybe a KGB agent.

She was very guarded, but the others were openly saying they were looking

forward freedom and to new regime that would make life a little easier

for them. BD: Are you a little more sympathetic

to the clarinet because you are superb player?

BD: Are you a little more sympathetic

to the clarinet because you are superb player? MK: Who knows? It’s a good guess,

but what I’m saying is that I’m a composer by correction because I do

this with a lot of pieces. Some, of course, I don’t touch.

I don’t want to exaggerate the extent of this kind of activity, but

it does happen. I’ve learned this from a lot of painters, and also

from Martha Graham. I worked with her when she did a ballet of mine

about ten years ago, and at the same time she was doing some old ballets.

She was constantly changing, constantly revising, and it’s no skin

off anybody’s nose. Years ago, I had the temerity to always compose

in ink, but in those days I didn’t revise anything. As I grew older

and more seasoned, I realized that it’s important to keep yourself flexible.

I can admit that I have made a mistake, or and that a passage could

be improved.

MK: Who knows? It’s a good guess,

but what I’m saying is that I’m a composer by correction because I do

this with a lot of pieces. Some, of course, I don’t touch.

I don’t want to exaggerate the extent of this kind of activity, but

it does happen. I’ve learned this from a lot of painters, and also

from Martha Graham. I worked with her when she did a ballet of mine

about ten years ago, and at the same time she was doing some old ballets.

She was constantly changing, constantly revising, and it’s no skin

off anybody’s nose. Years ago, I had the temerity to always compose

in ink, but in those days I didn’t revise anything. As I grew older

and more seasoned, I realized that it’s important to keep yourself flexible.

I can admit that I have made a mistake, or and that a passage could

be improved. BD: Where’s music going today?

BD: Where’s music going today? MK: Who knows? I haven’t been

to Germany that recently. When I was there, I remember they always

have their contemporary composers perform on the radio, but not at

the choice hours. They’re always late at night, so that’s a good

point. When I was in Czechoslovakia, however

— about fifteen or eighteen years ago

— the composers there were treated liked heroes.

Prague is a city filled with musicians — wonderful

players, and a lot of composers — and

it means something to be a composer. Now in my own little community

in Rhinebeck, New York, I have a feeling of being a member of the community,

like perhaps in the olden days of Bach, maybe, when a local composer wrote

music. I have many friends in that area who play with the local orchestras.

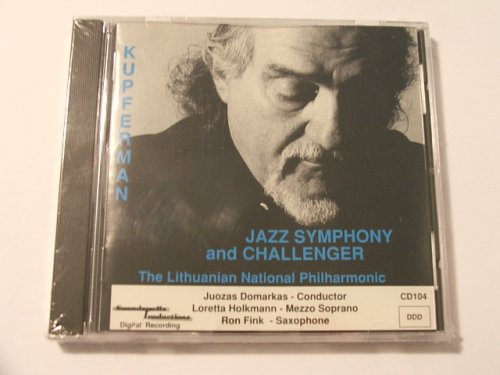

The Hudson Valley Philharmonic has commissioned three big works of mine,

including this Jazz Symphony. They commissioned it and did

the initial performance. I feel I am a member of that community,

so when I write, although I don’t think of audiences as you were asking

before, I do feel that my music is related to a place, to some meaningful

way of life. I’m a member of a community, and my job is to write

music for that community.

MK: Who knows? I haven’t been

to Germany that recently. When I was there, I remember they always

have their contemporary composers perform on the radio, but not at

the choice hours. They’re always late at night, so that’s a good

point. When I was in Czechoslovakia, however

— about fifteen or eighteen years ago

— the composers there were treated liked heroes.

Prague is a city filled with musicians — wonderful

players, and a lot of composers — and

it means something to be a composer. Now in my own little community

in Rhinebeck, New York, I have a feeling of being a member of the community,

like perhaps in the olden days of Bach, maybe, when a local composer wrote

music. I have many friends in that area who play with the local orchestras.

The Hudson Valley Philharmonic has commissioned three big works of mine,

including this Jazz Symphony. They commissioned it and did

the initial performance. I feel I am a member of that community,

so when I write, although I don’t think of audiences as you were asking

before, I do feel that my music is related to a place, to some meaningful

way of life. I’m a member of a community, and my job is to write

music for that community.© 1991 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in New York City on December 9, 1991. Portions were broadcast on WNIB five days later, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry, and also to Carson Cooman, for their help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.