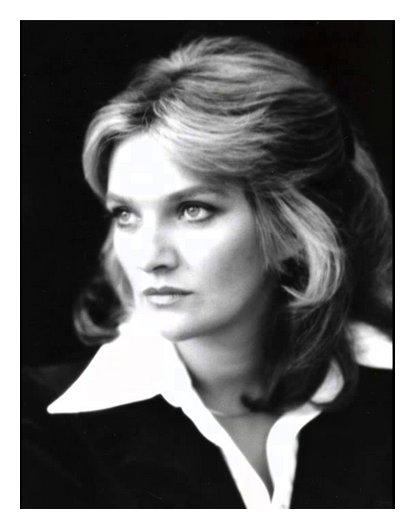

| Born in Bangor, County Down, Northern

Ireland on April 24, 1944, Norma Burrowes studied at The Queen's University

of Belfast and then at Royal Academy of Music with Flora Nielsen and Rupert

Bruce-Lockhart. She made her professional debut with the Glyndebourne Touring

Opera Company as Zerlina, in 1970. The same year she made her debut at the

Royal Opera House in London as Fiakermilli, and at the Glyndebourne Festival

as Papagena. She also sang in various productions with the English Opera

Group, including Henry Purcell's The Fairy-Queen,

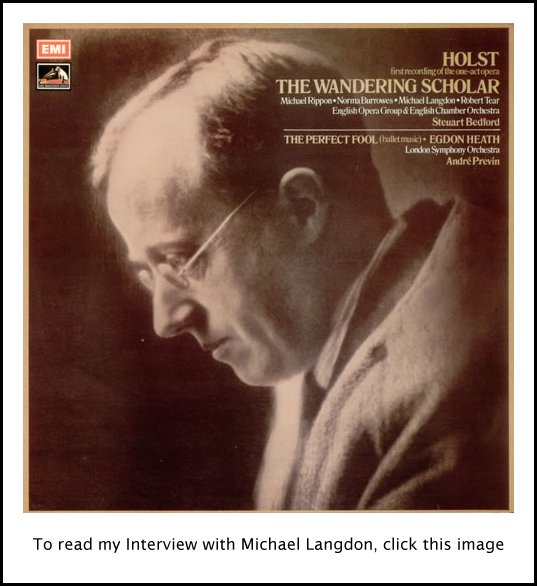

King Arthur, and Dido and Aeneas. Burrowes joined the English National Opera in 1971, and quickly began to appear on the international scene, notably at the Salzburg Festival, the Paris Opéra, and the Aix-en-Provence Festival. She made her Metropolitan Opera debut in 1979 as Blondchen. She began her career singing mostly soubrette roles including Susanna and Despina, and she gradually expanded to light coloratura parts such as Adina, Norina, Marie, Oscar, Nanetta and Zerbinetta, later adding more lyrical roles such as Pamina, Juliette and Manon. She also excelled in operas by Purcell, Handel, and Haydn, in which she can be heard on several recordings. From 1969 to 1980 she was married to the conductor Steuart Bedford, with whom she recorded the role of Alison in Holst's The Wandering Scholar. A singer with a pure and silvery voice, secure coloratura technique and delightful stage presence, Burrowes retired from the stage in 1982. She married former tenor Émile Belcourt, and in 1992 joined him at the University of Saskatoon as a vocal coach. In 1994 they resettled with their family in Toronto, where Burrowes is currently a member of the vocal faculty at York University. [See my Interview with Émile Belcourt.] |

BD: I assume though that you are looking forward

to going back to the career at some point?

BD: I assume though that you are looking forward

to going back to the career at some point? BD:

Physically rather than vocally?

BD:

Physically rather than vocally? BD:

So where should the balance be between drama and voice.

BD:

So where should the balance be between drama and voice.  NB: She’s a real woman who knows exactly what

she’s doing; very attractive; a hair-raiser! [Both laugh] She

has got great capacity for love, but she’s the boss.

NB: She’s a real woman who knows exactly what

she’s doing; very attractive; a hair-raiser! [Both laugh] She

has got great capacity for love, but she’s the boss. NB:

Yes, and of course you have people outside to tell you. But above all

you must never force. Sometimes when you are in big places you are

tempted to force, and you feel you just can’t possibly sing it there.

But then, of course, if you do that, it is even more difficult to come to

a small house because people can hear so much more clearly. Recitals

are always much more demanding than being on the operatic stage because it’s

just you and the piano, and you don’t have the orchestra to try to ride over.

Also every little nuance just has to be just perfect.

NB:

Yes, and of course you have people outside to tell you. But above all

you must never force. Sometimes when you are in big places you are

tempted to force, and you feel you just can’t possibly sing it there.

But then, of course, if you do that, it is even more difficult to come to

a small house because people can hear so much more clearly. Recitals

are always much more demanding than being on the operatic stage because it’s

just you and the piano, and you don’t have the orchestra to try to ride over.

Also every little nuance just has to be just perfect. BD:

So then I assume you’ve told your agent no more Zerbinettas!

BD:

So then I assume you’ve told your agent no more Zerbinettas! NB: In English... well, in American actually,

which is very difficult! I did it in Toronto, and there is a lot of

speaking in it, but everybody else that was cast was American. I remember

the first thing I had to do was to come on and say, [in an American accent]

“Damn, damn, damn, damn!”

At the first rehearsal, I came onto the stage and said it in an English accent

[demonstrates], and they just fell about laughing!

NB: In English... well, in American actually,

which is very difficult! I did it in Toronto, and there is a lot of

speaking in it, but everybody else that was cast was American. I remember

the first thing I had to do was to come on and say, [in an American accent]

“Damn, damn, damn, damn!”

At the first rehearsal, I came onto the stage and said it in an English accent

[demonstrates], and they just fell about laughing!  BD: And because it’s such a limited number of people,

then a greater percentage of them will be of the social set?

BD: And because it’s such a limited number of people,

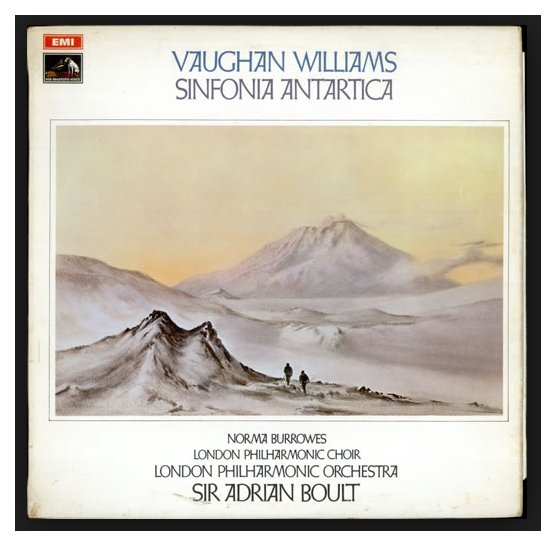

then a greater percentage of them will be of the social set? NB: Yes, that would be the connection

— they’re all English. I haven’t done a great deal

of Holst, but I’ve done quite a lot of Vaughan Williams.

NB: Yes, that would be the connection

— they’re all English. I haven’t done a great deal

of Holst, but I’ve done quite a lot of Vaughan Williams. BD:

Was it satisfying at all to performing in it on television?

BD:

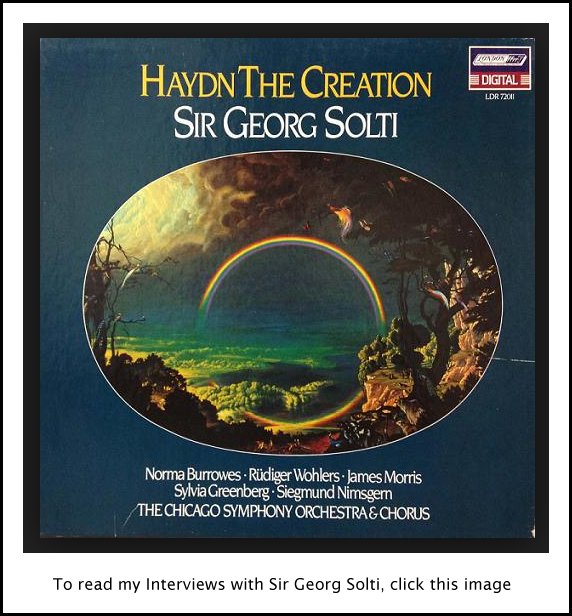

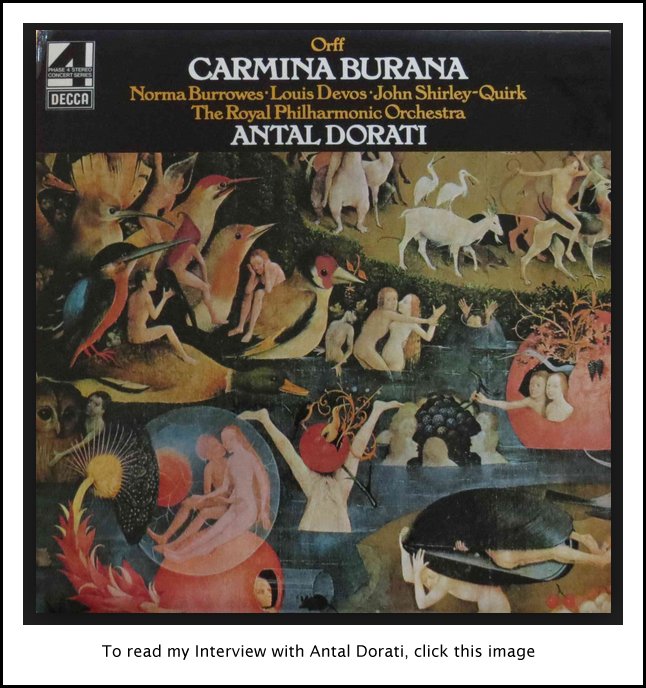

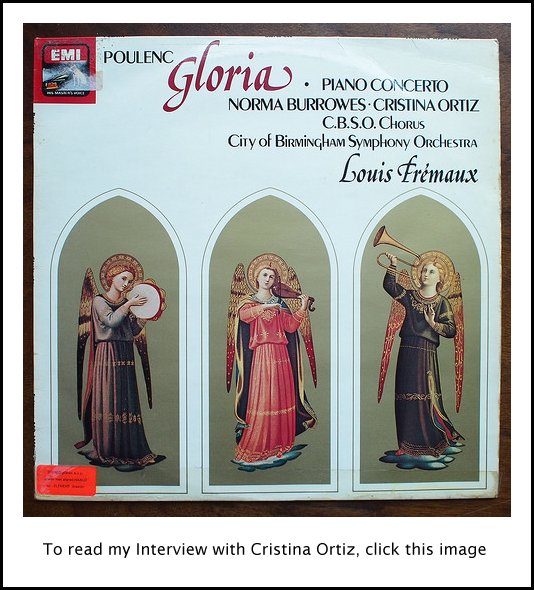

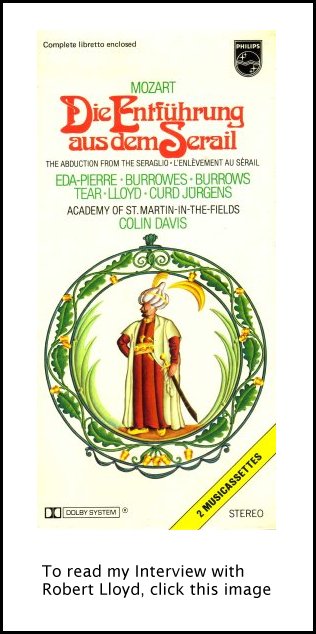

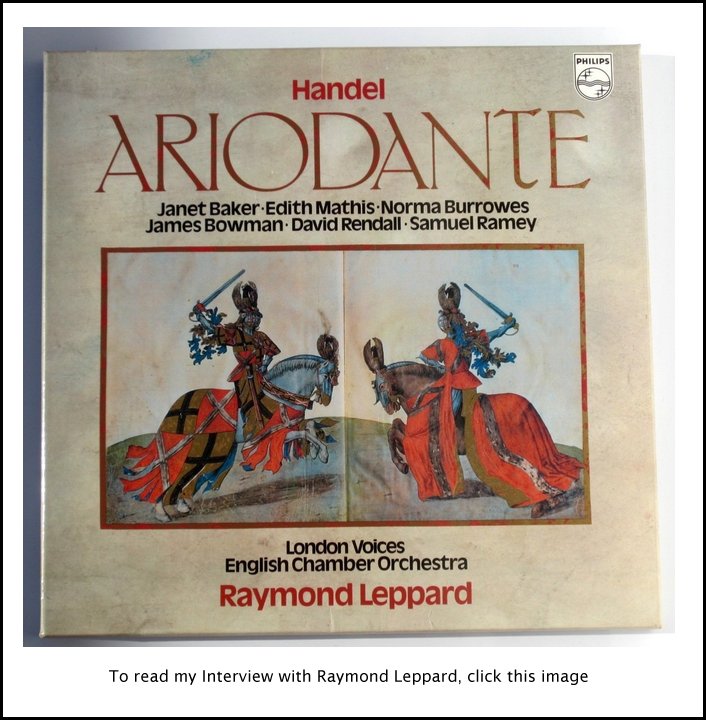

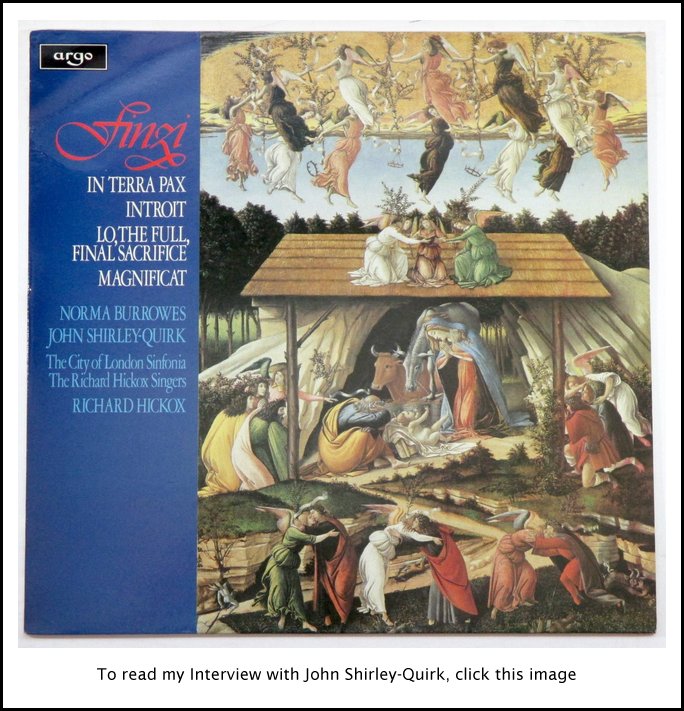

Was it satisfying at all to performing in it on television?A few more of the recordings

made over the years by

Norma Burrowes and some of my other guests. |

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on August 6, 1986. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1994, 1997, and again in 1999. This transcription was made in 2015, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.