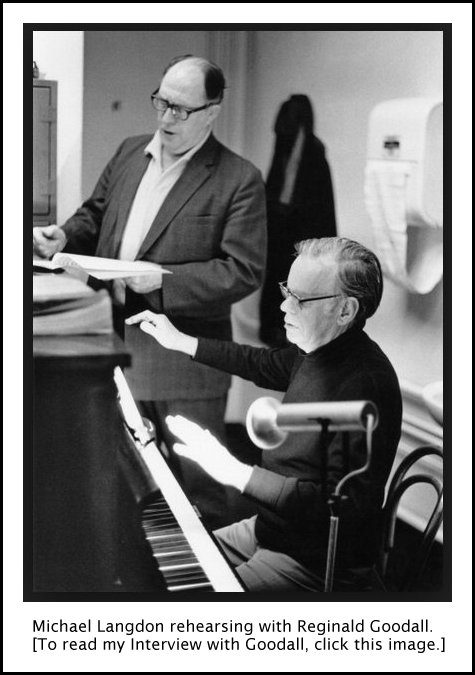

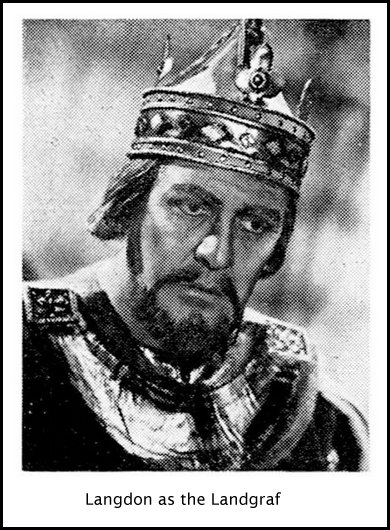

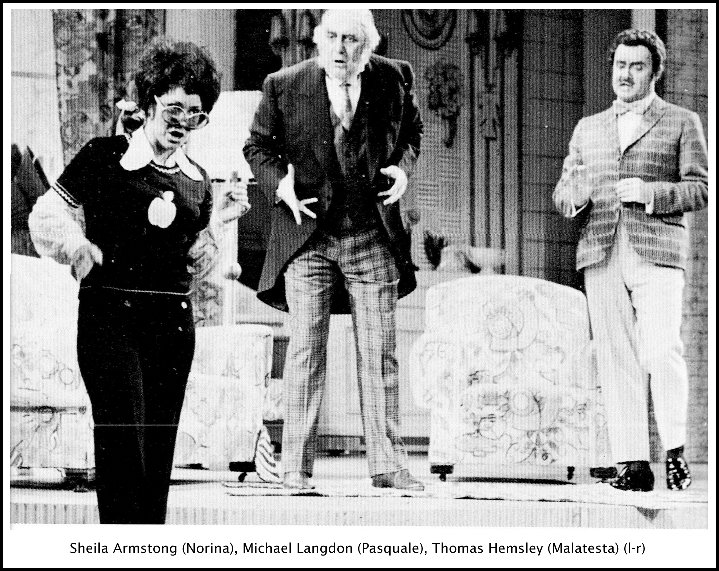

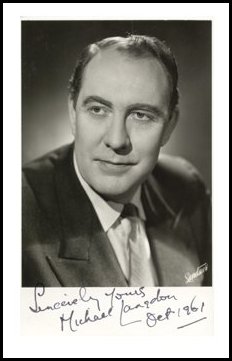

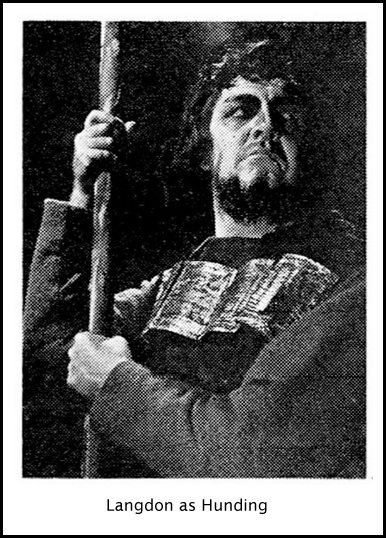

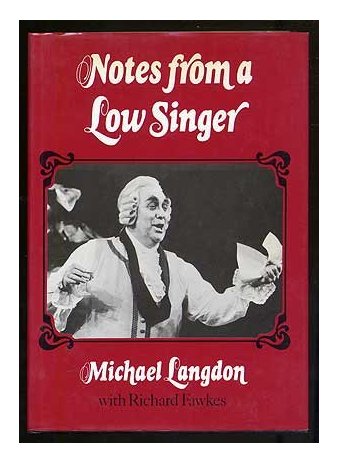

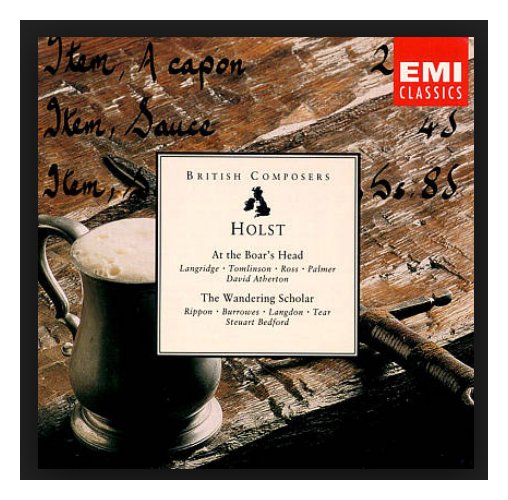

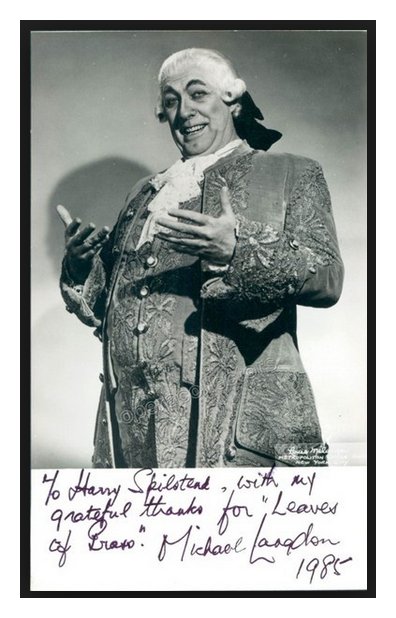

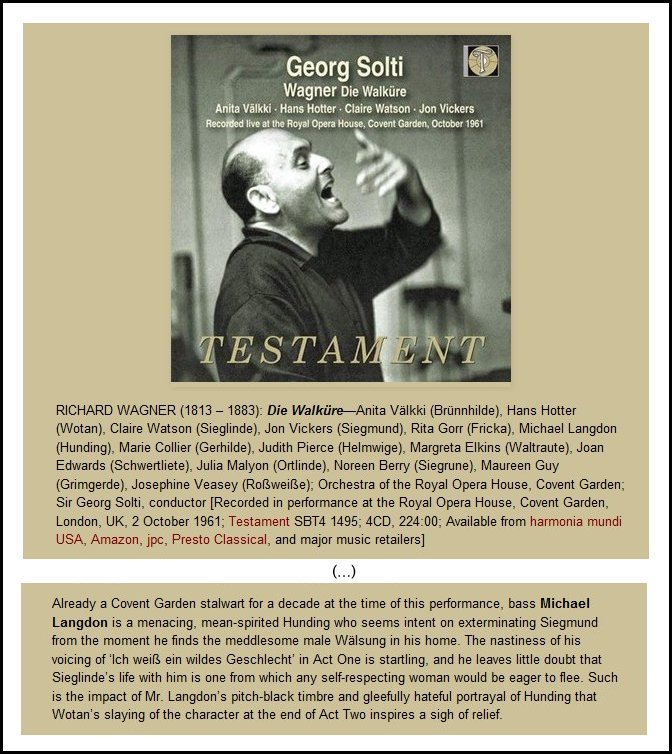

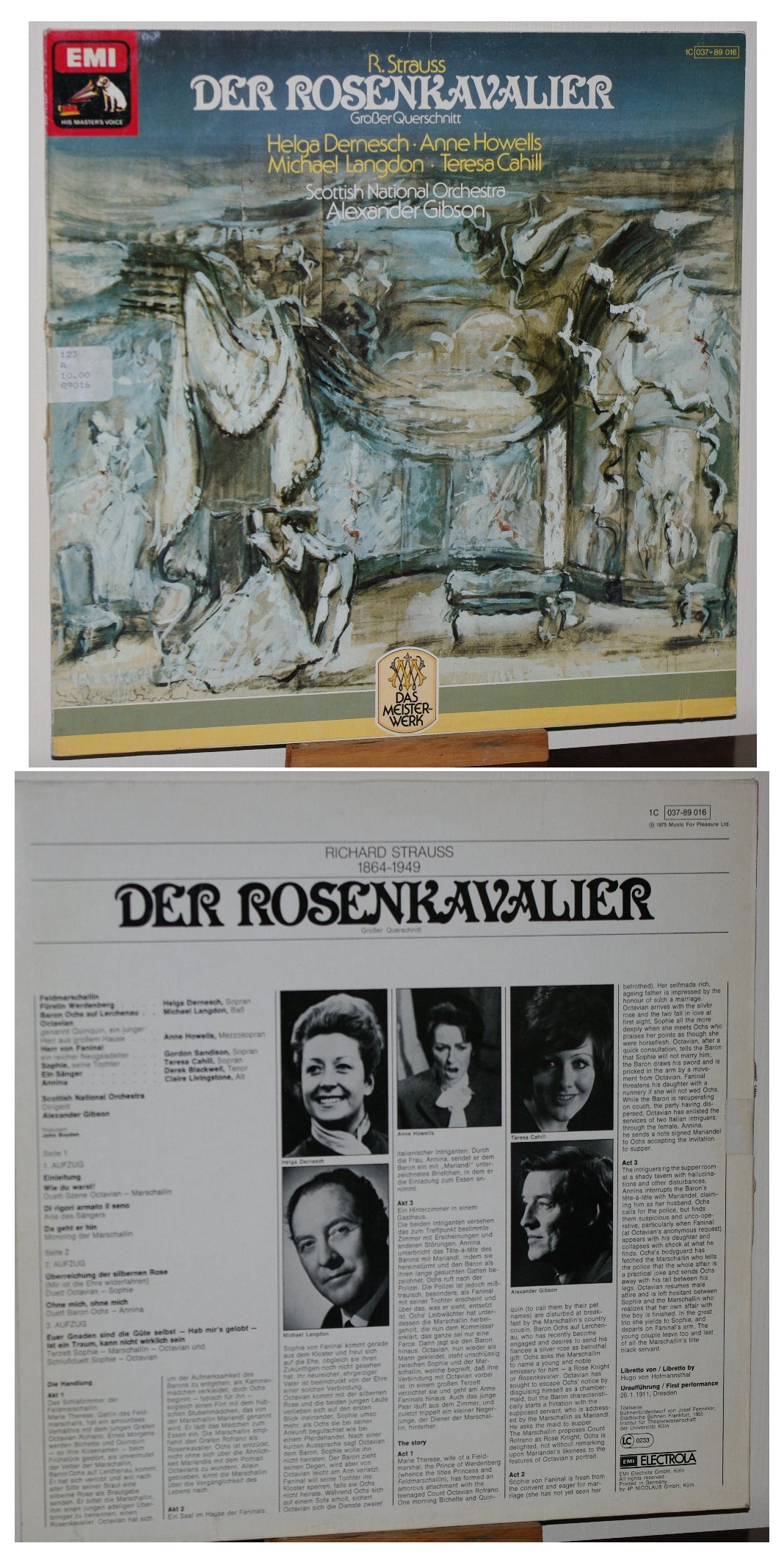

After studying in London, Michael Langdon (November 12, 1920 - March 12, 1991) joined the Covent Garden Chorus in 1948, making his solo debut with the company as the Nightwatchman in Arthur Bliss' The Olympians during a performance in Manchester. By the 1950 - 1951 season, Langdon was being heard as Sparafucile and Varlaam and, during the following season, he created the role of Lieutenant Ratcliffe in Britten's Billy Budd. For the Coronation season, the bass' King "upheld the honor of the resident company" against the Aïda of Maria Callas, the Amneris of Giulietta Simionato, and the Radames of Kurt Baum. The same season, Langdon created the Recorder of Norwich in Britten's Gloriana. In 1955, he shared with Frederick Dalberg the role of the He-Ancient in the first performances of Tippett's The Midsummer Marriage. Opportunities grew and his repertory gradually expanded to include Sarastro, Osmin, Daland, Hunding, Fafner, Hagen, Rocco, Kecal, Don Basilio, Bottom in Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Verdi's Grand Inquisitor. Two Strauss roles came within Langdon's orbit -- Count Waldner in Arabella, and Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier. After studying the role in Vienna with bass baritone Alfred Jerger (the first Mandryka in Arabella), Langdon went forward to more than a hundred performances of the role. After retiring from the stage in 1977, Langdon assumed the directorship of the National Opera Studio for some eight years, proving himself an able instructor in the stagecraft required of young singers. His autobiography, Notes From a Low Singer, issued in 1982, reflects the writer's dry wit and his commitment to the professionalism required by his art. Among Langdon's recordings is a disc of excerpts from Der Rosenkavalier which provides a memento of the singer's participation in a Scottish Opera production; and his malignant Claggart is heard under the composer's direction. -- From a biography by Erik Eriksson

|

ML: Very much from what I’m able to see of it.

With the very heavy rehearsal schedule, there’s not much time to get around.

People always seem to think that being an opera singer and seeing all these

famous cities, you have a chance get a street map and go around and visit

all the places of interest. It’s often very difficult to do much other

than commute between the theater and the hotel. From what I have seen,

it’s very awe-inspiring city, especially as I tend to look over the wrong

shoulder when crossing the road! I’ve always done that in the States.

Driving on the left in England, you always look the wrong way for the traffic.

But after you’ve had a couple of shaves with the Chicago bus, you quickly

learn to look the right way! [Both laugh]

ML: Very much from what I’m able to see of it.

With the very heavy rehearsal schedule, there’s not much time to get around.

People always seem to think that being an opera singer and seeing all these

famous cities, you have a chance get a street map and go around and visit

all the places of interest. It’s often very difficult to do much other

than commute between the theater and the hotel. From what I have seen,

it’s very awe-inspiring city, especially as I tend to look over the wrong

shoulder when crossing the road! I’ve always done that in the States.

Driving on the left in England, you always look the wrong way for the traffic.

But after you’ve had a couple of shaves with the Chicago bus, you quickly

learn to look the right way! [Both laugh] BD: But I must admit myself when I listen to it Meistersinger I like the added weight

of the basses who sing Hans Sachs. I’d rather hear the Hagen sing Sachs

than the Wotan sing Sachs.

BD: But I must admit myself when I listen to it Meistersinger I like the added weight

of the basses who sing Hans Sachs. I’d rather hear the Hagen sing Sachs

than the Wotan sing Sachs.

BD: Now let me ask about one specific instance here.

When Hagen is giving Siegfried the draught, there’s a trill going on in the

orchestra and all of a sudden the trill changes. We know that at that

point Siegfried’s mind has been clouded. So is Siegfried’s mind changed

first and then the trill changes?

BD: Now let me ask about one specific instance here.

When Hagen is giving Siegfried the draught, there’s a trill going on in the

orchestra and all of a sudden the trill changes. We know that at that

point Siegfried’s mind has been clouded. So is Siegfried’s mind changed

first and then the trill changes? BD: But what if they updated the whole thing and

made it consistent?

BD: But what if they updated the whole thing and

made it consistent? BD: Tell me about Karl Rankl.

BD: Tell me about Karl Rankl. ML: By and large I’m not for it. Here, the

Opera School of Chicago do what I do in my own National Opera Studio in London.

They teach the young singers the roles in the original language first, and

that is important because in translation invariably get changes in notation

to accommodate the different language. When you are a young singer,

or if when you’re doing a role for the first time, you’ll learn those changes

in notation as a matter of course, and when you come to put it back in the

original, you find yourself with a problem. The same problem does not

occur when you coming into your own language because you can say an opera

in English and forget a line, and dub another one at the drop of a hat because

it’s your language, even if it means altering notation on the spot.

So I firmly believe that whenever possible, opera should be in the original.

Now I’m going to make a proviso here. When it comes to introducing non-operatic

audiences to opera, that is the time when opera can profitably be put into

English so that people can hear the story and follow it and get it going.

But for big houses, to always sing in the vernacular is a mistake.

If you want the greatest protagonists you’ve got to do it in the original.

You’re not going to get Domingo learning Carmen in English for four performances.

ML: By and large I’m not for it. Here, the

Opera School of Chicago do what I do in my own National Opera Studio in London.

They teach the young singers the roles in the original language first, and

that is important because in translation invariably get changes in notation

to accommodate the different language. When you are a young singer,

or if when you’re doing a role for the first time, you’ll learn those changes

in notation as a matter of course, and when you come to put it back in the

original, you find yourself with a problem. The same problem does not

occur when you coming into your own language because you can say an opera

in English and forget a line, and dub another one at the drop of a hat because

it’s your language, even if it means altering notation on the spot.

So I firmly believe that whenever possible, opera should be in the original.

Now I’m going to make a proviso here. When it comes to introducing non-operatic

audiences to opera, that is the time when opera can profitably be put into

English so that people can hear the story and follow it and get it going.

But for big houses, to always sing in the vernacular is a mistake.

If you want the greatest protagonists you’ve got to do it in the original.

You’re not going to get Domingo learning Carmen in English for four performances. ML: I was schooled in German. I was used to

it. I think I did sing Wagner in English very, very early on at Covent

Garden. I’ve got a feeling that very first year that I did something...

it might have been Fafner-Stimme, but it very quickly went into German, and

I’ve never sung in any other language. Just like Rosenkavalier. I’ve sung one act

of Rosenkavalier in English in my

whole life.

ML: I was schooled in German. I was used to

it. I think I did sing Wagner in English very, very early on at Covent

Garden. I’ve got a feeling that very first year that I did something...

it might have been Fafner-Stimme, but it very quickly went into German, and

I’ve never sung in any other language. Just like Rosenkavalier. I’ve sung one act

of Rosenkavalier in English in my

whole life. BD: The Kleiber Rosenkavalier had a cast that knew the

work and had done it on stage.

BD: The Kleiber Rosenkavalier had a cast that knew the

work and had done it on stage.

See my Interview with Helga Dernesch See my Interview with Anne Howells

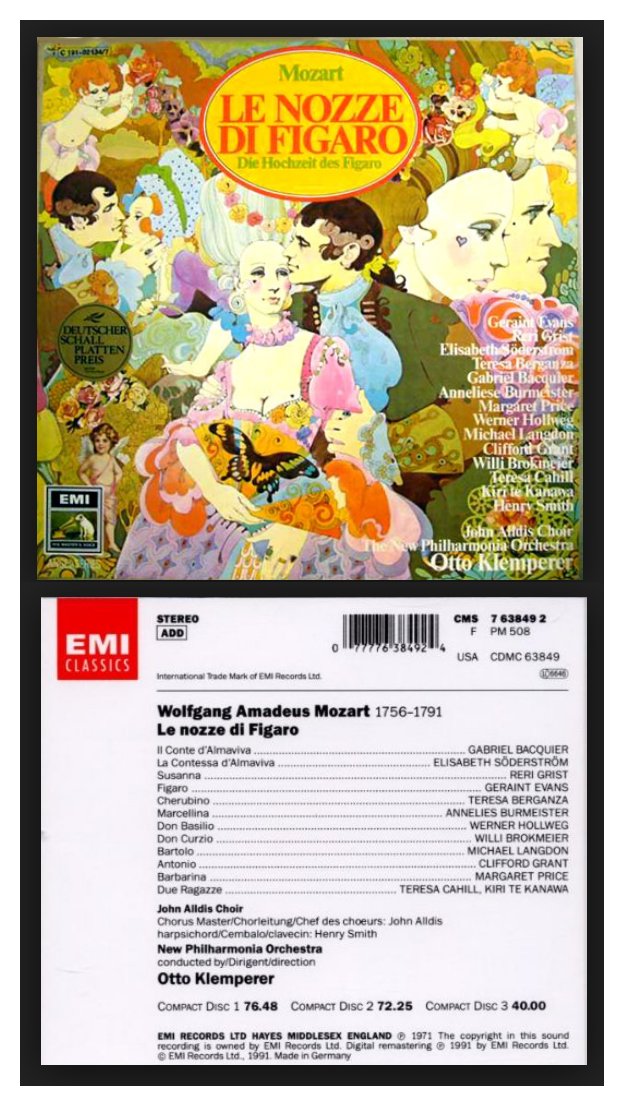

See my Interview with Elisabeth Söderström See my Interview with Teresa Berganza See my Interview with Margaret Price (who, like Te Kanawa, would later sing the Countess!) |

© 1981 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded backstage at the Opera House in Chicago on June 2, 1981. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1985, 1995, and 2000. This transcription was made in 2014, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.