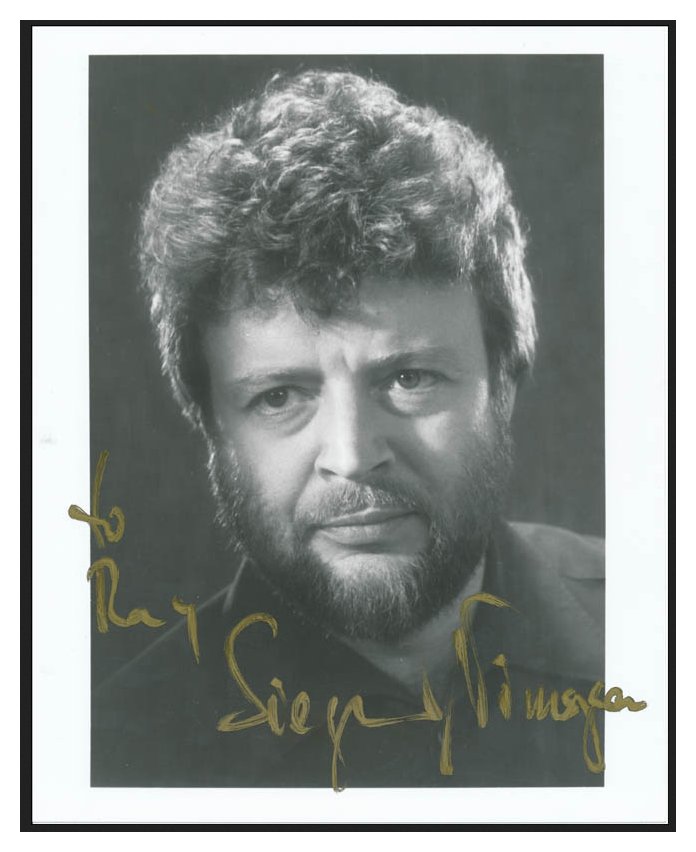

| Born: January 14, 1940 - Stiring-Wendel,

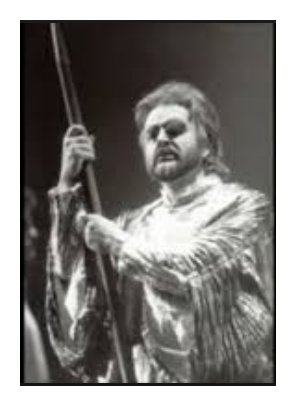

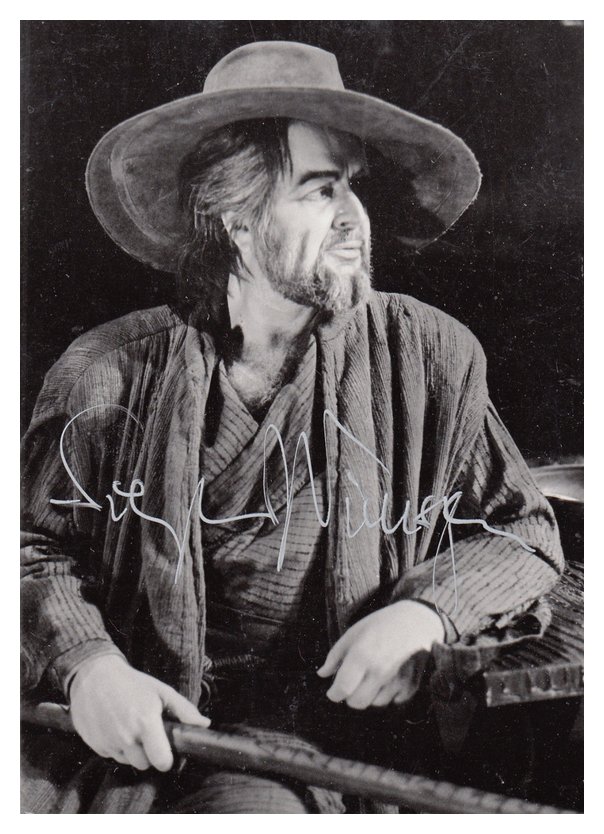

Saarland, Germany The German bass-baritone, Siegmund Nimsgern, has for many years belonged to the group of elite international singers. After his school-leaving examination Siegmund Nimsgern studied music education. Musicology, German, and philosophy. He was a student in Saarbrücken of Sibylle Fuchs, Jakob Stämpfli, and Paul Lohmann. He won four first prizes in important vocal competitions and soon thereafter became one of the most successful German lied, oratorio, and opera singers. In 1965 Siegmund Nimsgern made his debut as a concert artist. His operatic debut followed in 1967 when he appeared as Lionel in Tchaikovsky’s The Maid of Orleans in Saarbrücken, where he sang until 1971. In 1970 he made his Salzburg Festival debut. From 1971 to 1974 he was a member of the Deutsche Oper am Rhein in Düsseldorf. He made his British debut in 1972 as a soloist in La Damnation de Faust. In 1973 he made his first appearance at London’s Covent Garden as Amfortas, and he also made debuts at Milan’s La Scala and the Paris Opéra. In 1974 he made his USA debut as Jokanaan at the San Francisco Opera. He made his Metropolitan debut in New York as Pizarro in October 1978, and returned there as Jokanaan in 1981. From 1983 to 1985 he appeared as Wotan at the Bayreuth Festivals. In addition to Radio and recording studios, Siegmund Nimsgern’s regular sphere of activity includes all of the major opera houses, such as La Scala (Milano), the Metropolitan Opera (New York), Covent Garden (London), Opéra de Paris, the Wiener Staatsoper, the opera houses in Chicago, San Francisco, Buenos Aires, Berlin, Hamburg, Munich, Rome (Santa Cecilia), etc., as well as the music festivals in Munich, Salzburg, Flanders, Israel, Florence, Orange, Berlin, Ansbach, and Bayreuth. Important conductors such as Claudio Abbado, Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, Riccardo Chailly, Colin Davis, Christoph von Dohnányi, Carlo Maria Giulini, Herbert von Karajan, Carlos Kleiber, Erich Leinsdorf, Jean Martinon, Zubin Mehta, Riccardo Muti, Seiji Ozawa, Wolfgang Sawallisch, Georg Solti, Horst Stein, and many others, have worked and continue to work together with Siegmund Nimsgern. LP and CD records as well as numerous ‘private recordings’ give proof of his vocal and interpretations skills. Among Siegmund Nimsgern’s other roles were Telramund, Alberich, Günther, the Dutchman, Macbeth, Iago, and Luna. As Lieder (Schubert, Schumann, Johannes Brahms, Wolf, etc.) and oratorio singer (J.S. Bach, George Frideric Handel, L.v. Beethoven, Felix Mendelssohn, etc.), but above all as character and ‘Helden’ baritone in the opera (Mozart, L.v. Beethoven, Verdi, Georges Bizet, Wagner, Strauss, Puccini, Alban Berg, George Enescu, and many others), Siegmund Nimsgern belongs without question to the most prominent vocal and stage personalities in the contemporary music scene. -- From the Bach-Cantatas website

-- Names which are links in this box and below refer to my Interviews elsewhere on this website. BD |

Siegmund Nimsgern at Lyric Opera of Chicago

1979 - Tristan (Kurwenal) with Knie, Vickers, Dunn, Sotin; Decker, Poettgen,

Oswald

1982 - Tristan (Kurwenal) with Martin, Vickers, Denize, Sotin, Negrini, Cook; Leitner, Poettgen, Oswald Tosca (Scarpia) with Bumbry/Marton, Domingo/Luchetti, Kavrakos, Andreolli, Tajo; Rudel, Gobbi, Pizzi 1983 - Flying Dutchman (Dutchman) with Carson, Schunk, Sotin/Moll; Perick, Ponnelle 1984 - Frau ohne Schatten (Barak) with Marton, Johns, Zschau, Dunn, Voketaitis; Janowski, Corsaro, Chase 1986-87 - Parsifal (Amfortas) with Vickers, Troyanos, Sotin, Becht, Salminen/Kennedy; Perick, Pizzi 1987-88 - Tosca (Scarpia) with Scotto, Ciannella, Patterson, Andreolli, Tajo; Tilson Thomas, Kellner, Pizzi 1988-89 - Salome (Jokanaan) with Ewing, Fassbaender, King, Farina; Slatkin, Aster, Hall Aïda (Amonasro) with Susan Dunn/Kasrashvili/Marc, Lamberti/Giacomini/Bartolini, Zajick, Giaotti; Richard Buckley, Joël, Halmen, Tallchief 1989-90 - [Opening Night] Tosca (Scarpia) with Marton/Neblett, Jóhannsson/Giacomini, Runey, Andreolli, Tajo; Bartoletti, de Tomasi, Pizzi Siegmund Nimsgern with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

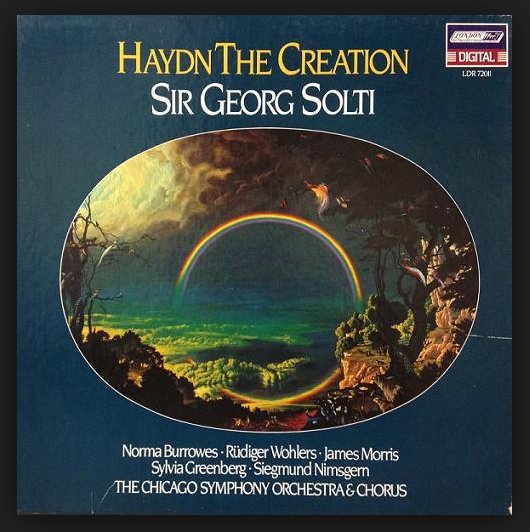

(all performances conducted by Sir Georg Solti, Margaret Hillis Chorus Director) November 1981 [Also Decca Recording

which won a 1983 Grammy] - Creation

(Adam) with Burrowes,

Greenberg, Wohlers, Morris

Apirl 1983 [Also Carnegie Hall, NY] - Das Rheingold (Wotan) with Schnaut, Jerusalem, Becht, Tear, DeGaetani, Smith, Howell April 1985 - St. Matthew Passion (Bass Solos) with Schoene, Rolfe-Johnson, Coburn, Fassbaender, Moser

|

BD: Let me ask about productions. Stage

directors seem to be taking off into many different directions. Do

you approve of all that’s going on?

BD: Let me ask about productions. Stage

directors seem to be taking off into many different directions. Do

you approve of all that’s going on?

BD:

You seem to have a very large repertoire...

BD:

You seem to have a very large repertoire... SN: It’s a compromise for sure, but it’s better

than nothing. And some pieces — like the Chausson

— are never done onstage, so a concert is not bad. I have

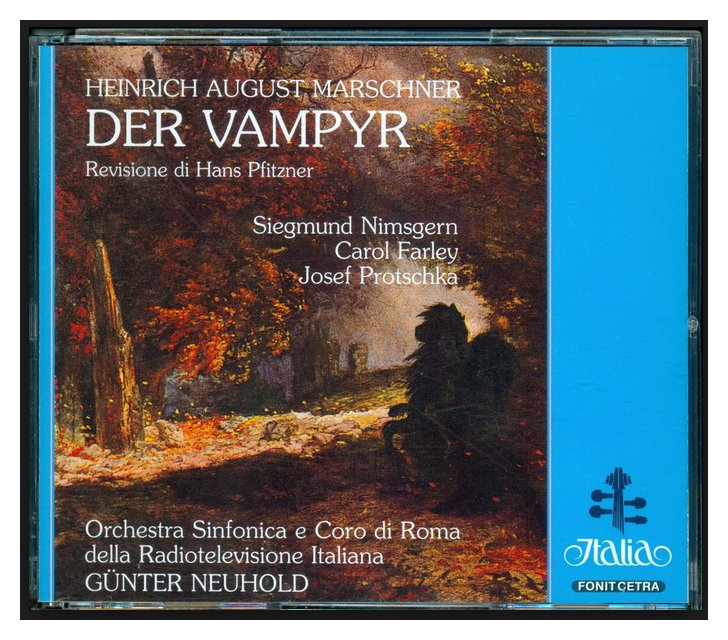

done many things in Italy for the radio, RAI. Of about 20 different

times, maybe 10 are never done onstage... Dr. Faust of Busoni, Vampyr of Marschner, Feuersnot of Strauss, but that one was

done in Munich in a production by Gian Carlo Del Monico, the son of Mario

the tenor. The baritone is a nice part, and it is one hour of singing

— half of it in the basket twenty feet high! The last scene is on

the balcony, which is also high. At first I was a little afraid, a

bit anxious, but now it is OK. Two days after leaving here I go back

and sing it again. Strauss wrote it for a high baritone, but it must

be a dark baritone because it is a Wagner-sized orchestra.

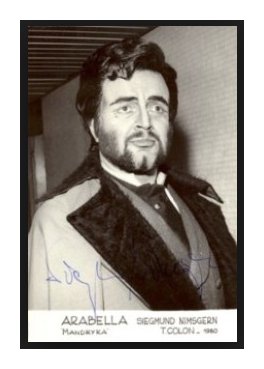

Mandryka is a marvelous part and is the biggest of the Strauss baritones.

The whole opera is not so marvelous — I prefer Frau ohne Schatten. Barak is one

of the few roles in my repertoire who are really good guys. He is

a little bit stupid, as always the good guys are, but I like it. There

is no pushing and no menacing. There is only one minute when he tries

to kill his wife, but this comes from his good character. He really

loves her and when he thinks she has betrayed him, he gets furious.

SN: It’s a compromise for sure, but it’s better

than nothing. And some pieces — like the Chausson

— are never done onstage, so a concert is not bad. I have

done many things in Italy for the radio, RAI. Of about 20 different

times, maybe 10 are never done onstage... Dr. Faust of Busoni, Vampyr of Marschner, Feuersnot of Strauss, but that one was

done in Munich in a production by Gian Carlo Del Monico, the son of Mario

the tenor. The baritone is a nice part, and it is one hour of singing

— half of it in the basket twenty feet high! The last scene is on

the balcony, which is also high. At first I was a little afraid, a

bit anxious, but now it is OK. Two days after leaving here I go back

and sing it again. Strauss wrote it for a high baritone, but it must

be a dark baritone because it is a Wagner-sized orchestra.

Mandryka is a marvelous part and is the biggest of the Strauss baritones.

The whole opera is not so marvelous — I prefer Frau ohne Schatten. Barak is one

of the few roles in my repertoire who are really good guys. He is

a little bit stupid, as always the good guys are, but I like it. There

is no pushing and no menacing. There is only one minute when he tries

to kill his wife, but this comes from his good character. He really

loves her and when he thinks she has betrayed him, he gets furious. BD: When Wotan conceives Siegmund, does he think

Siegmund will save the gods, or does he know it will take another generation,

a Siegfried?

BD: When Wotan conceives Siegmund, does he think

Siegmund will save the gods, or does he know it will take another generation,

a Siegfried? BD: Is it wrong to sing three Wotans and also

Gunther in the same cycle?

BD: Is it wrong to sing three Wotans and also

Gunther in the same cycle?|

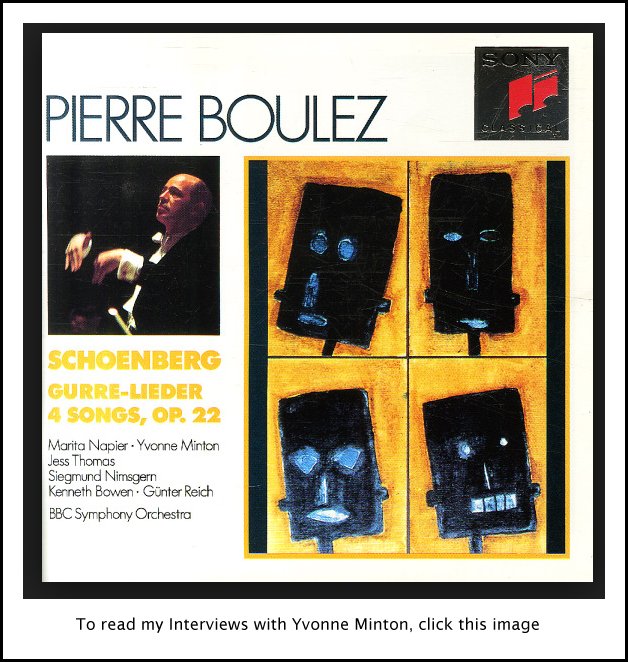

A few more recordings made by Siegmund Nimsgern which include some of my other interview guests . . .

To read my Interview with Helen Donath, click HERE. To read my Interview with Walter Berry, click HERE. To read my Interview with Arleen Auger, click HERE. To read my Interview with Helmuth Rilling, click HERE.

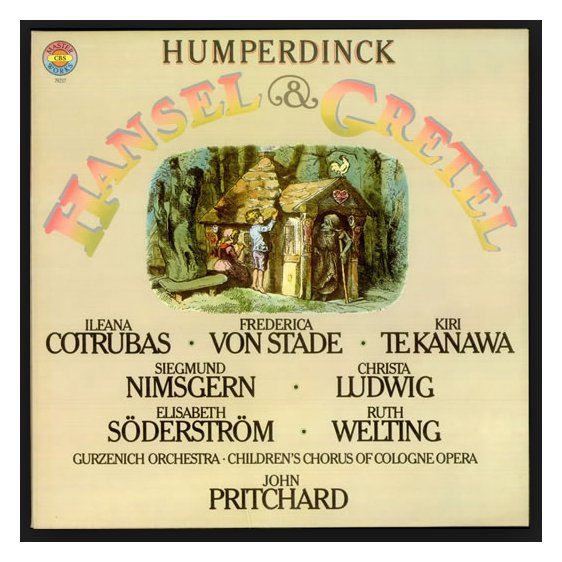

To read my Interview with Ileana Cotrubas, click HERE. To read my Interview with Kiri te Kanawa, click HERE. To read my Interview with Elisabeth Söderström, click HERE. To read my Interview with Ruth Welting, click HERE. To read m Interviews with John Pritchard, click HERE.

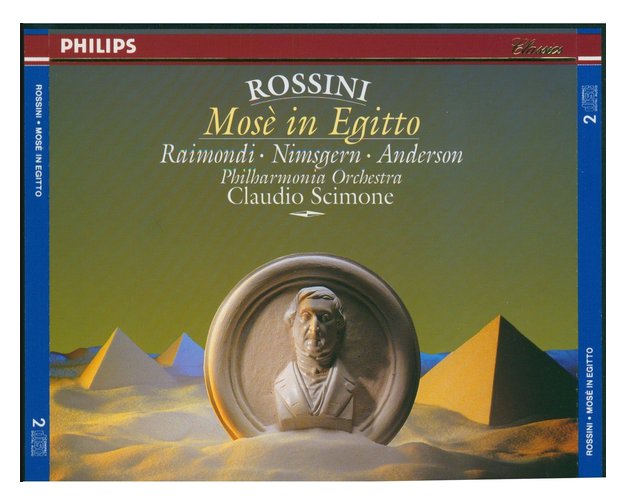

To read my Interview with Ruggero Raimondi, click HERE. To read my Interview with June Anderson, click HERE.

|

© 1982 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Nimsgern's apartment in Chicago

on November 8, 1982. A transcription was made and part of it appeared

in Opera Scene Magazine in April,

1983; the Wagner sections were published in Wagner News in July of that same year.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1988, 1990, 1995, 1997, and 2000.

The transcription was re-edited and posted on this website very early in 2016.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.