A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

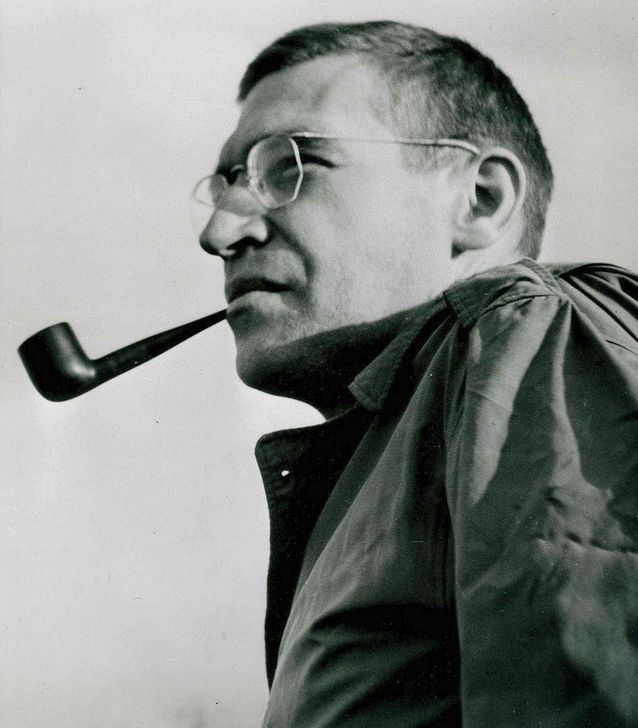

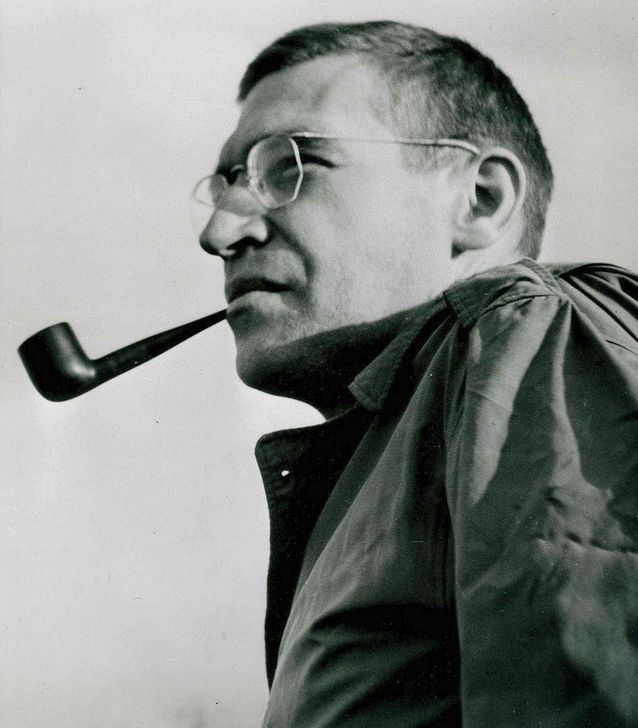

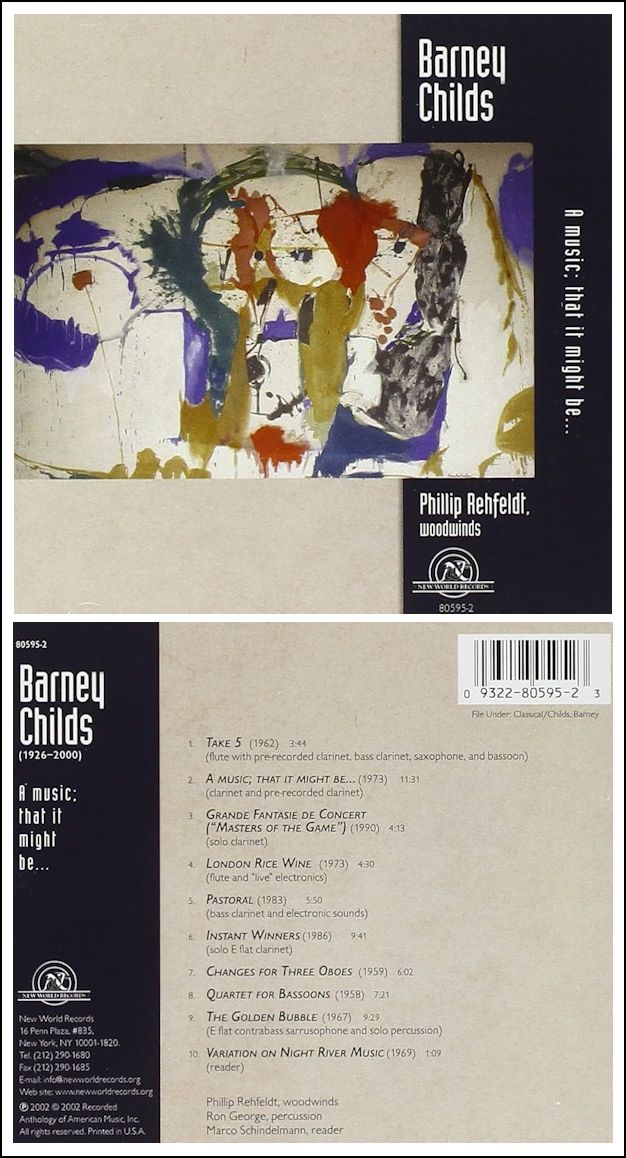

Born in Spokane, Wash. on Feb. 13, 1926, Barney Childs led a colorful life as both a scholar and a composer. Childs attended the University of Nevada where he earned his B.A. As a Rhodes Scholar, Childs went on to earn a B.A. and M.A. in English language and literature at Oxford University. In addition, he earned a Ph.D. in English and music from Stanford University. Childs was largely a self-taught composer. In the 1950's he did, however, have the opportunity to study with Carlos Chavez and Aaron Copland at Tanglewood. He also spent time studying with Elliott Carter in New York. Many of his pieces were performed throughout the United States by the late 1950's. As a teacher, he began his career in the English Department at the University of Arizona from 1961-65. He later advanced to dean of Deep Springs College from 1965-69. From 1969-71, Childs served as composer-in-residence at the Wisconsin Conservatory of Music in Milwaukee. The remainder of his career was spent teaching with Johnston College and the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Redlands from 1971-93. During his career, Childs was active with a number of publications. He served as poetry editor of "Genesis West" and co-editor of "The New Instrumentation" book series. He was co-founder of Advance Recordings and served as an associate editor for "Perspectives of New Music." Together with Phillip Rehfeldt (University of Redlands), Childs was

a performing participant in the commissioning series "Music for Clarinet

and Friend." He also served as co-editor (with Elliott Schwartz) of

the book "Contemporary Composers on Contemporary Music." Barney

Childs passed away on Jan. 11, 2000, leaving behind some 160 compositions

and the poetry text "The Poetry-I Book. A Collection of childs' Manuscripts"

is currently held and being processed in a special collection at the

University of Redlands.

== Biography from the website of the American

Compaosers Alliance

== Names which are links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

|

Ruskin's writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. He wrote essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale. He also made detailed sketches and paintings of rocks, plants, birds, landscapes, architectural structures and ornamentation. The elaborate style that characterised his earliest writing on art gave way in time to plainer language designed to communicate his ideas more effectively. In all of his writing, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society. Ruskin was hugely influential in the latter half of the 19th century

and up to the First World War. After a period of relative decline, his

reputation has steadily improved since the 1960s with the publication

of numerous academic studies of his work. Today, his ideas and concerns

are widely recognised as having anticipated interest in environmentalism,

sustainability, ethical consumerism, and craft. |

© 1990 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on November 26, 1990. Portions were broadcast on WNIB a few weeks later, and again in 1996. This transcription was made in 2025, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.