John McCabe obituary

by John Turner, The Guardian, Friday, 13 February, 2015 [Text only - photos and links added for this wepbage presentation] Prolific composer

and pianist of international standing

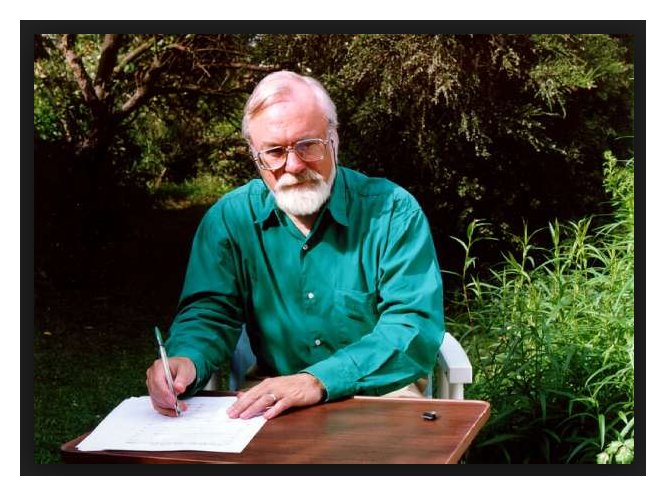

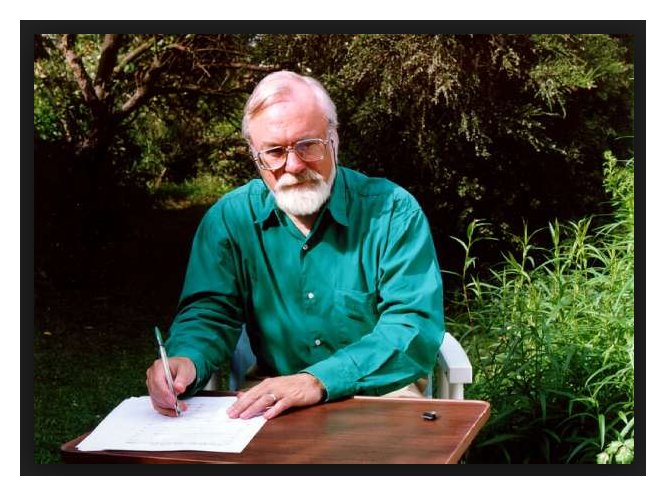

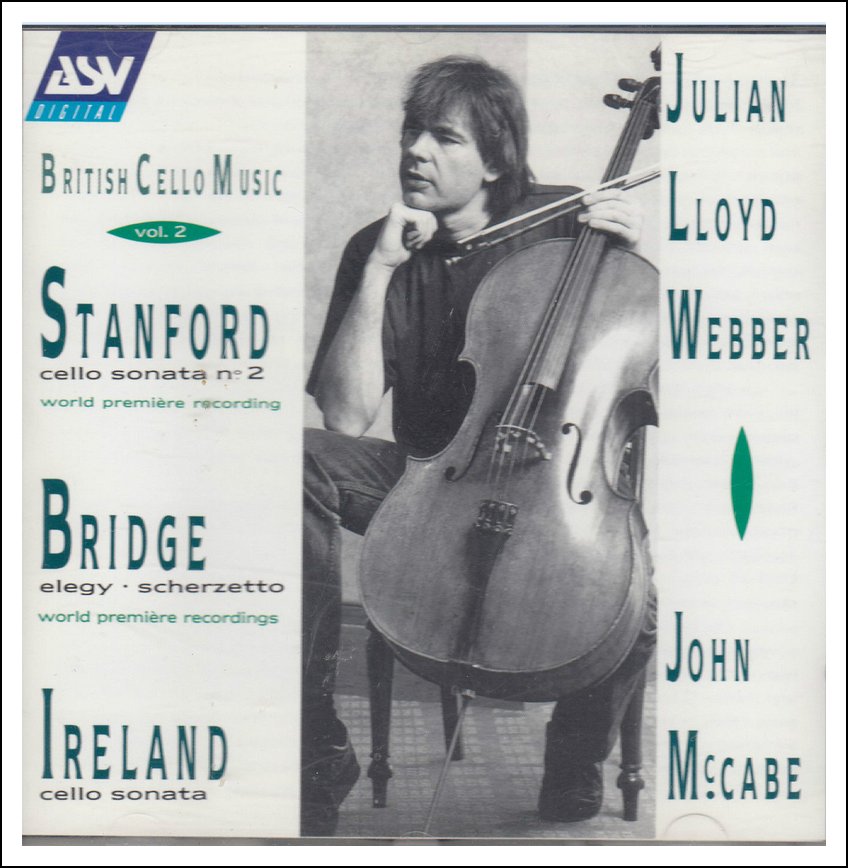

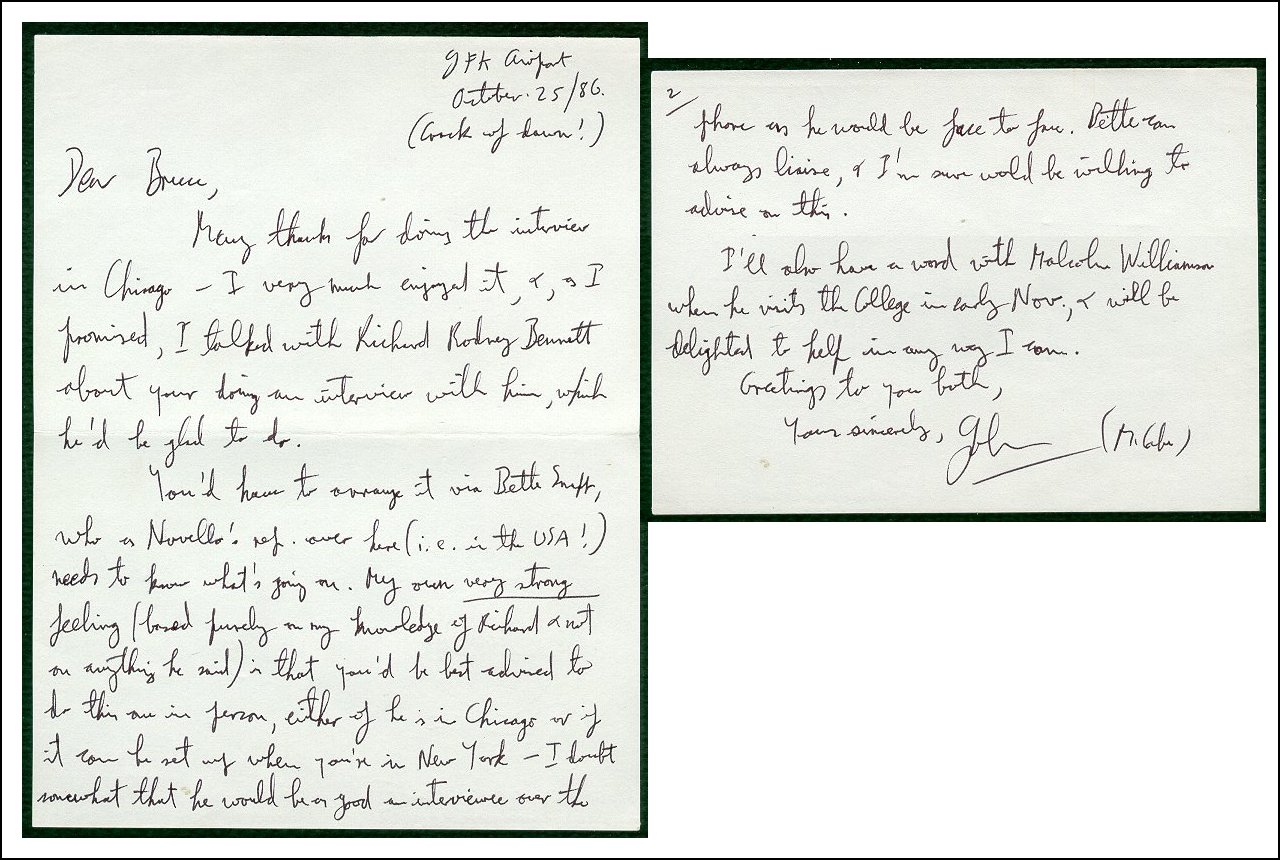

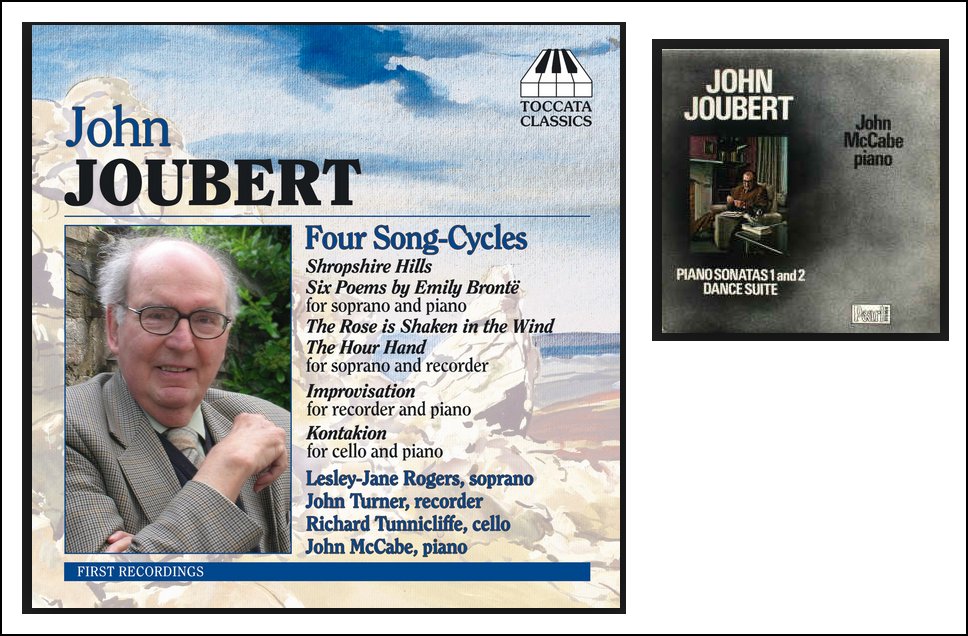

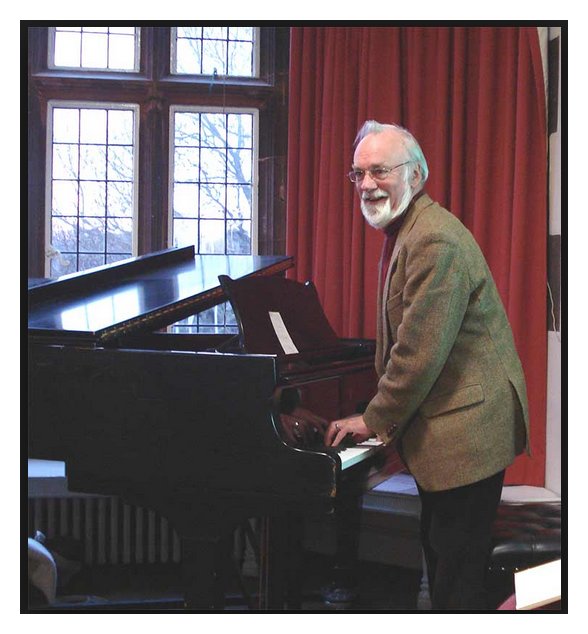

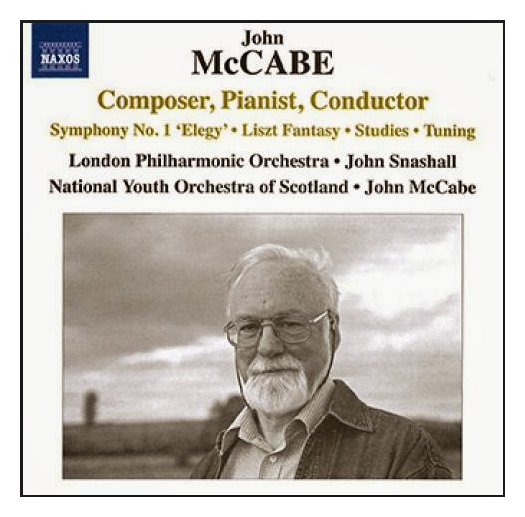

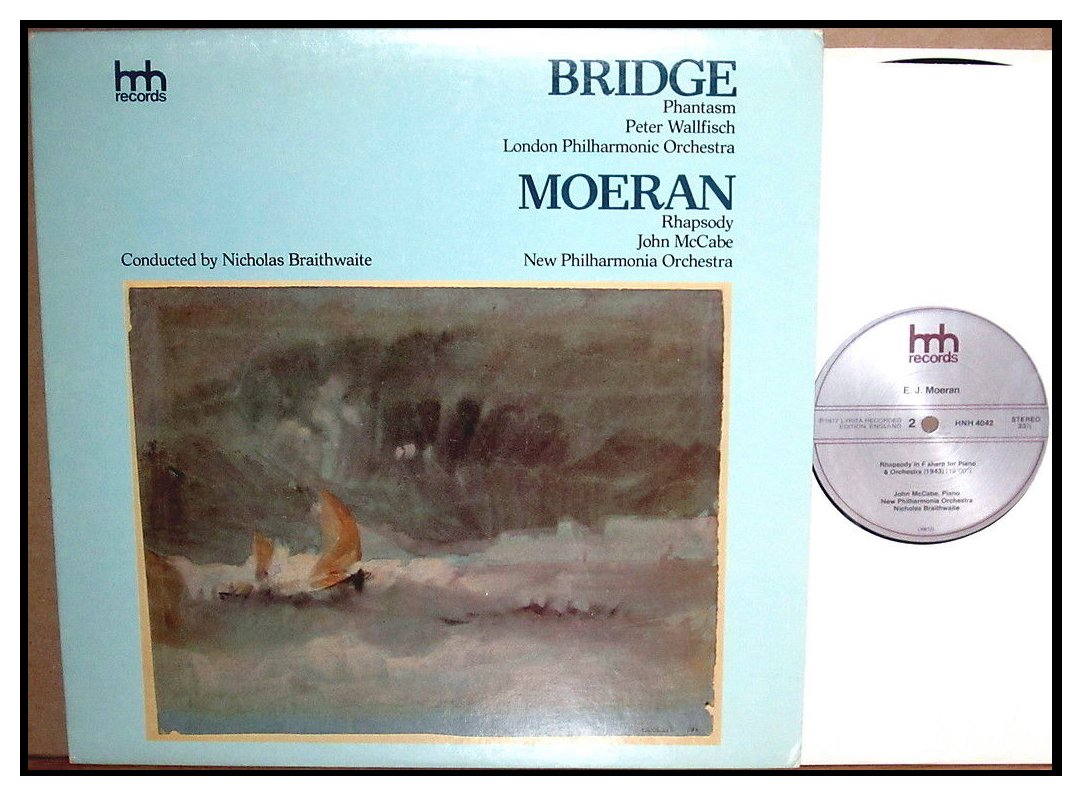

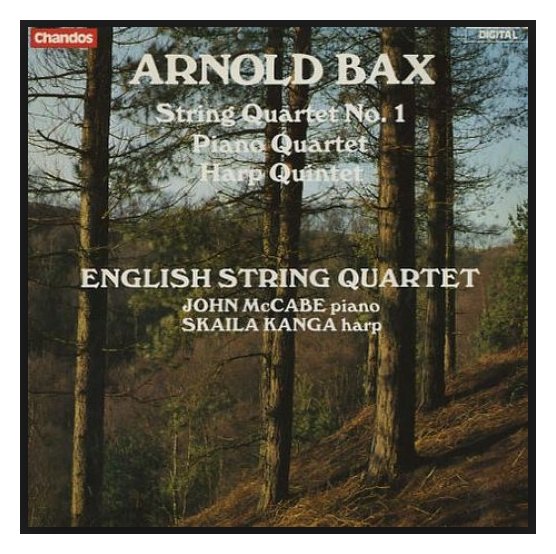

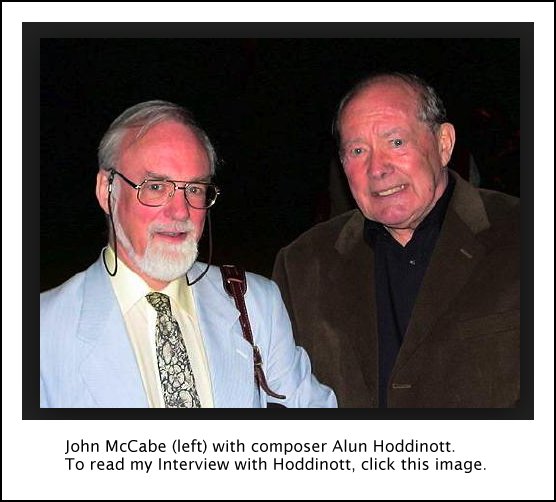

The gifted English composer and pianist John McCabe, who has died aged 75, was a remarkably rounded musician who was responsible for more than 200 compositions and pursued a busy solo career over several decades. As a pianist of international standing, he inspired many composers, including John Casken, Sir Richard Rodney Bennett and George Benjamin, to write solos and concertos for him. He relished accompanying, and formed partnerships with Julian Lloyd Webber (cello), Erich Gruenberg (violin), Ifor James (horn) and the singer Jane Manning.

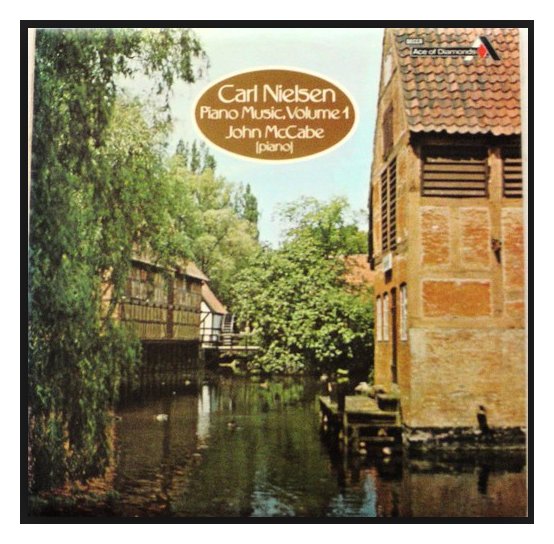

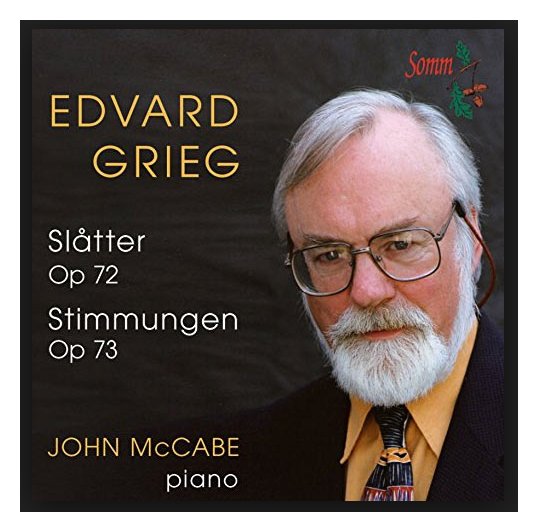

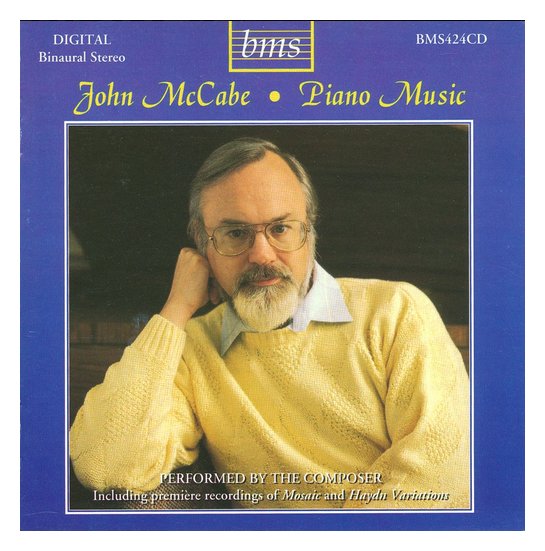

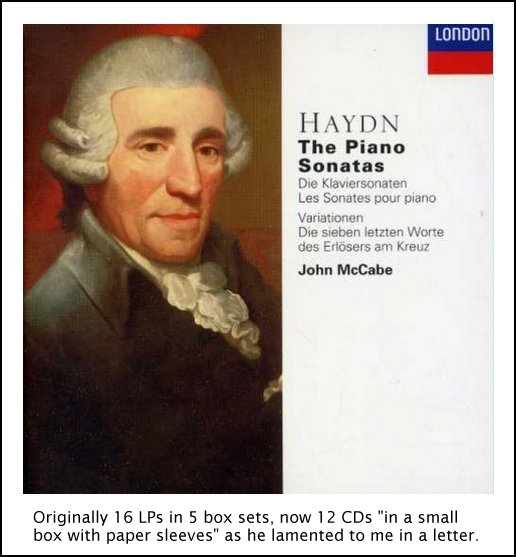

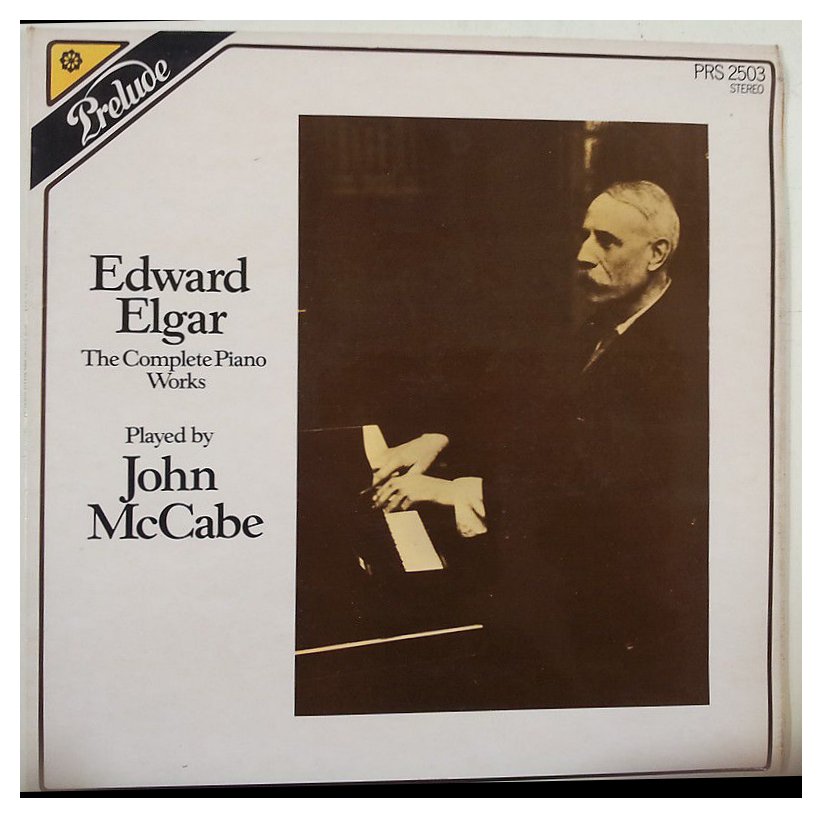

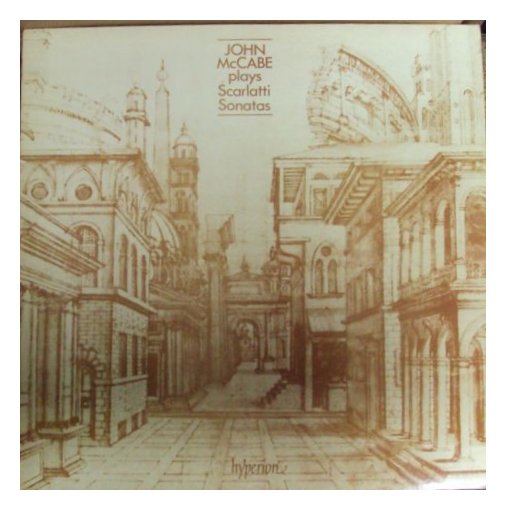

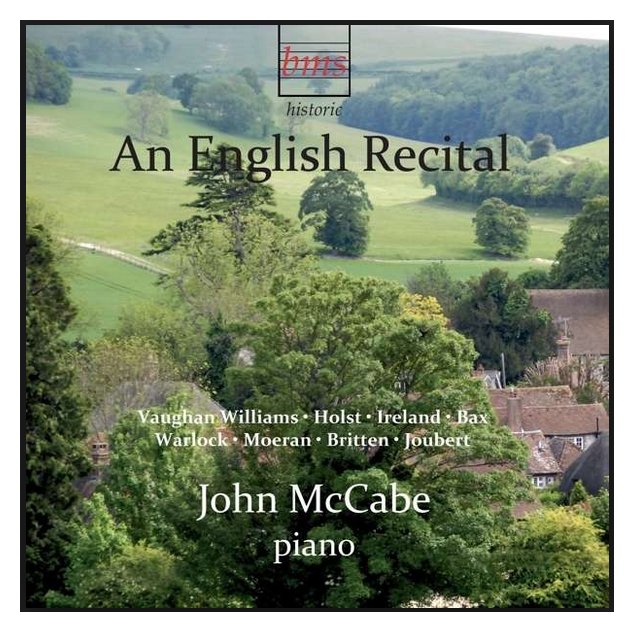

His first recording, a 1967 LP of songs by Charles Ives, Alexander Goehr and Gerard Schurmann, with the American soprano Marni Nixon, was both pioneering and revelatory, not least because Ives was largely ignored at that time. But McCabe’s Haydn piano sonatas and the complete piano music of Carl Nielsen are probably his most lasting pianistic legacy. McCabe’s technique was immaculate, sensitive and unshowy, as faithful as possible to the composer’s intentions. His preparation of scores was extremely thorough, often with every note fingered in pencil.

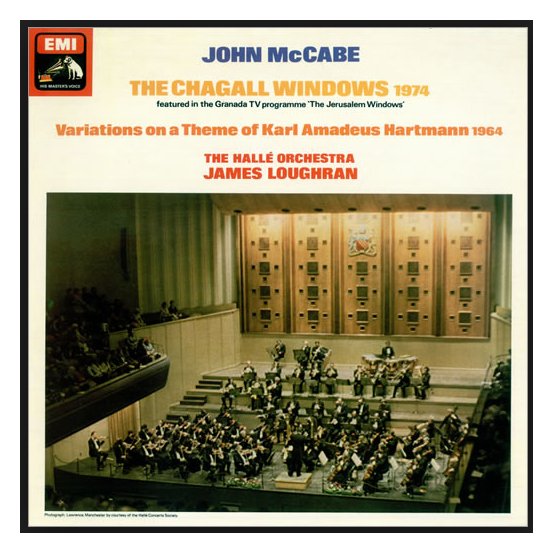

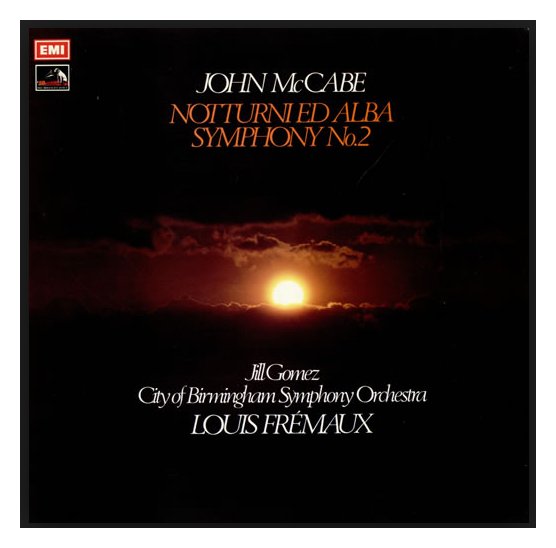

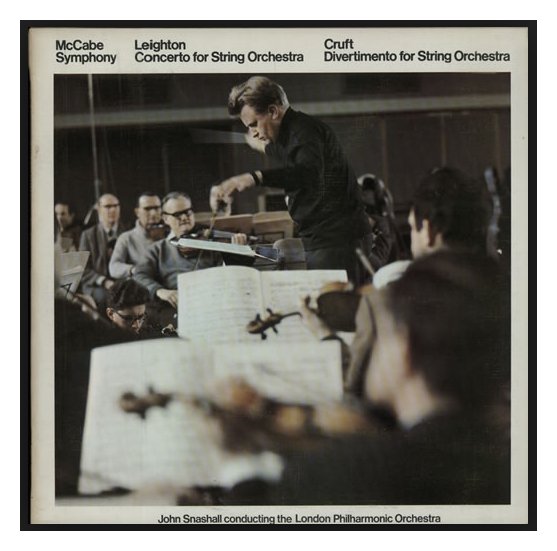

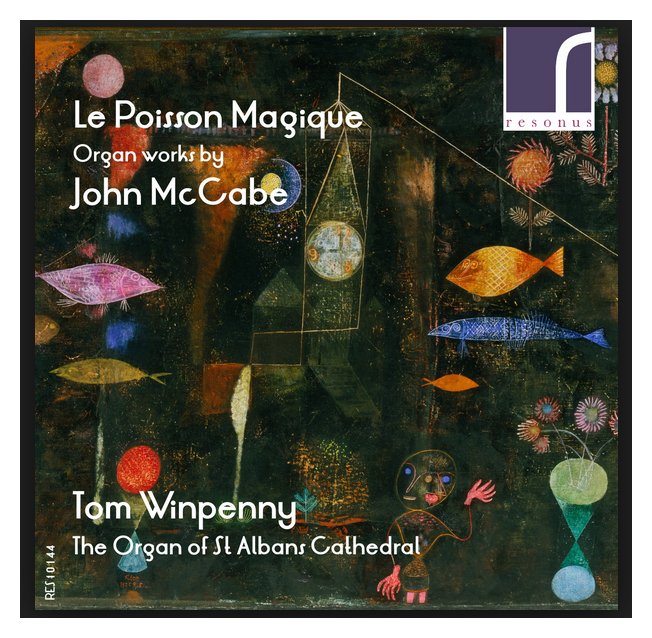

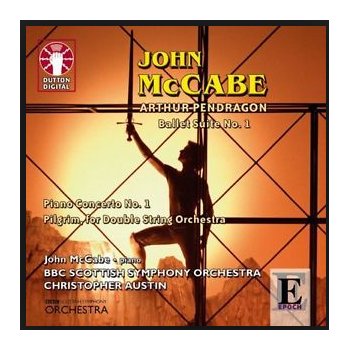

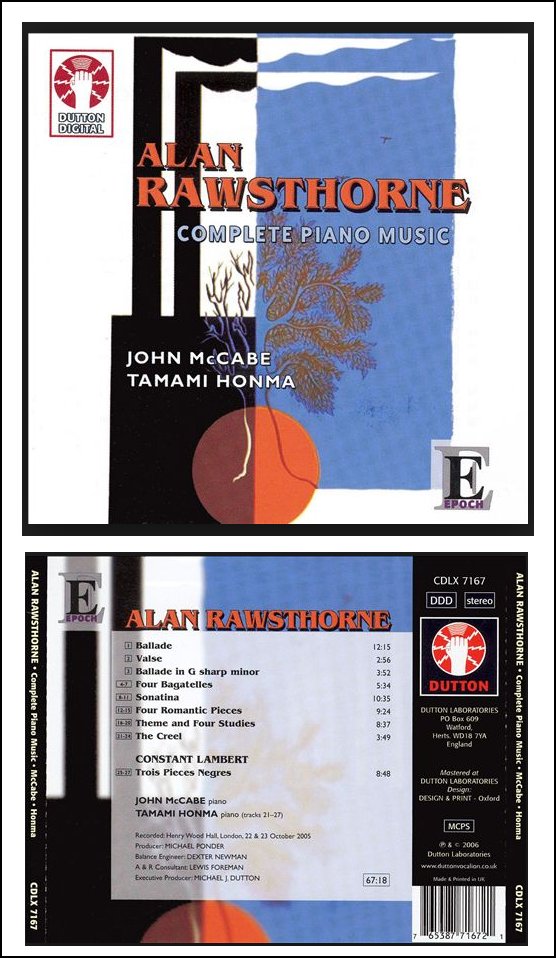

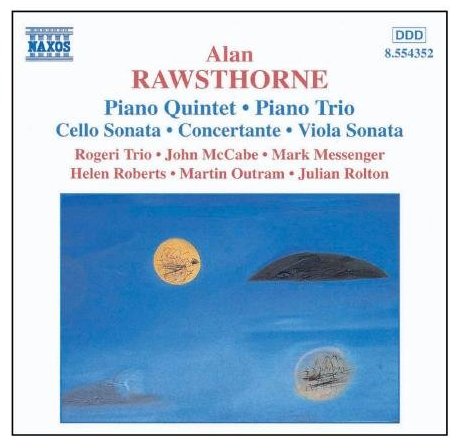

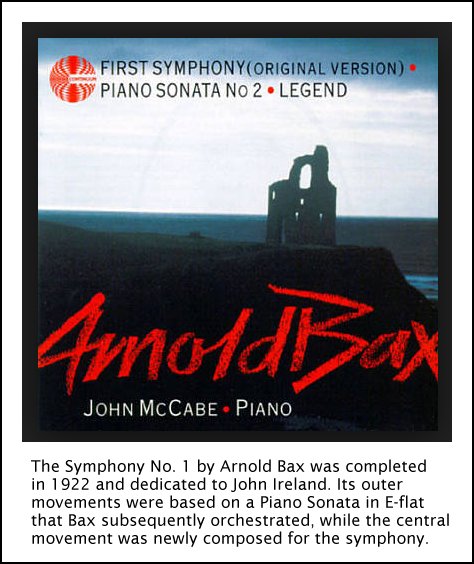

His compositional work is particularly noteworthy for its sense of colour; in the orchestral works there is often a striking use of percussion and brass to create ear-tickling sonorities, as in the much-admired orchestral song cycle Notturni ed Alba (1970). Landscape was frequently an inspiration for him; one of his best-loved works was the brass band piece Cloudcatcher Fells (1985), which reflected a lifelong love of the Lake District, while his series of “desert and rainforest” works drew on foreign landscapes relished on his worldwide trips. McCabe’s compositions covered most of the established forms, with the exception of grand opera, and included seven symphonies, three piano concertos, and concertos for most orchestral instruments. Also for piano, he composed a series of 13 studies, as well as the large-scale Tenebrae (1993) and Haydn Variations (1983). He leaves five full-length ballets, including Edward II (1995), commissioned by the Stuttgart Ballet, and Arthur Pendragon (1999) and Morte d’Arthur (2000), both for the Birmingham Royal Ballet. He wrote chamber music and choral music in abundance, as well as several sets of light educational pieces. McCabe regarded his composing and piano playing as equally balanced elements of his musical personality. But in addition he was a perceptive author on musical subjects, and an effective political crusader for British music and performers. His writings included the definitive life and works of his friend Alan Rawsthorne, and BBC Music Guides on the Haydn piano sonatas and Béla Bartók’s orchestral music. He was president of the British Music Society and the Rawsthorne Trust, and a patron of the William Alwyn Foundation. He also fought tenaciously with the Performing Rights Society for the interests of composers. McCabe was born in Huyton, near Liverpool. His father, Frank, was a research physicist, working on the development of transistors, and was one of the four children of Joseph McCabe, the free-thinking writer. His mother, Elisabeth Herlitzius, a talented watercolourist, was of German descent and came to England in the early 1920s with her father, an inventor of confectionery recipes. John was the only child of their marriage, and showed great precocity as a pianist and composer from the age of six. A childhood accident with fire in the home resulted in much time off school, which allowed his musical gifts to develop quickly. When he was eight he started piano lessons with Gordon Green, the well-known Liverpool pianist, at the Royal Manchester (now Royal Northern) College of Music, and he remained Green’s piano pupil for 17 years. His general schooling was at the Liverpool Institute (now the Liverpool Institute for Performing Arts), where his younger contemporaries included Paul McCartney and George Harrison. McCabe’s light-hearted recorder and piano piece Domestic Life (2000), with its catchy Merseybeat tunes, recalled those formative Liverpool years. He entered Manchester University to read music, and took lessons from the composer Thomas Pitfield, who was so astonished at his pupil’s facility that he maintained he could compose a piece on the top deck of a bus. He then went to the Royal Manchester College for a four-year postgraduate diploma in piano and composition. Many of his early successes date from this period: his Violin Concerto No 1 (1959) was played by Martin Milner with the Hallé Orchestra, and Variations on a Theme of Hartmann (1964) was taken up by the Hallé as a repertoire piece for many years.

After a year studying in Munich, from 1965 to 1968 McCabe was pianist in residence at Cardiff University, another fruitful period for composition, including Symphony No 1 (1965) performed by the Hallé under John Barbirolli, and the children’s opera The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1968), after CS Lewis. From 1968 onwards, he lived and worked in London, then Kent, as a freelance composer and pianist, although he also had a spell as director of the London College of Music from 1983 to 1990 and subsequent short tenures as a visiting professor at the universities of Melbourne and Cincinnati. He was appointed CBE in 1985. McCabe’s last completed works were a Proms commission, Joybox (2013), a choral work for the Hallé, Christ’s Nativity (2014), and a trumpet sonata. He was contemplating an eighth symphony, two more string quartets, and solo pieces for cello and piano. John married Hilary Tann in 1968; they were divorced in 1972. Two years later he married Monica Smith, who survives him. • John McCabe, composer and pianist, born 21 April 1939; died 13 February 2015 |

JMcC: I never have time off, really. I

very occasionally manage to get away for a short holiday

— maybe once every two years — and I like

to go walking. This year we did have a holiday, and we came over and

went on a tour in the west — the Grand Canyon and

Yosemite and all that, which I thought I’m never going to see when I’m over

here working. I might see one of them if I’m lucky but not as a vacation.

Then I read books and I watch films. I’m very interested in cricket!

JMcC: I never have time off, really. I

very occasionally manage to get away for a short holiday

— maybe once every two years — and I like

to go walking. This year we did have a holiday, and we came over and

went on a tour in the west — the Grand Canyon and

Yosemite and all that, which I thought I’m never going to see when I’m over

here working. I might see one of them if I’m lucky but not as a vacation.

Then I read books and I watch films. I’m very interested in cricket! BD: If you do not write for the public, for whom

do you write?

BD: If you do not write for the public, for whom

do you write? BD: When people write about your music, should

that be read before people come to the concerts?

BD: When people write about your music, should

that be read before people come to the concerts? JMcC:

It might be, yes. The accidents occur for all sorts of reasons and

become part of the piece. And the audience becomes part of the piece.

The tempo changes slightly because of the acoustics, because of the audience,

because of the cricket scores that day in my case. If England is doing

very well I might play faster... but all sorts of things go up to make a

performance, and of course in recording that doesn’t happen so much.

The acoustics might be better, but you take away the audience and you’ve taken

away part of the interactive process. But I don’t think it affects what

I said about the recording being a performance. You have to try and

conjure up your own audience. So you end up by trying to do the same

thing. Accidents happen, and some of the greatest recordings are of

live performances because of that electricity.

JMcC:

It might be, yes. The accidents occur for all sorts of reasons and

become part of the piece. And the audience becomes part of the piece.

The tempo changes slightly because of the acoustics, because of the audience,

because of the cricket scores that day in my case. If England is doing

very well I might play faster... but all sorts of things go up to make a

performance, and of course in recording that doesn’t happen so much.

The acoustics might be better, but you take away the audience and you’ve taken

away part of the interactive process. But I don’t think it affects what

I said about the recording being a performance. You have to try and

conjure up your own audience. So you end up by trying to do the same

thing. Accidents happen, and some of the greatest recordings are of

live performances because of that electricity.  BD: Let’s go the other direction then.

Should your music be played on instruments of the twenty-first and twenty-second

century, rather than the piano and instruments that we have now?

BD: Let’s go the other direction then.

Should your music be played on instruments of the twenty-first and twenty-second

century, rather than the piano and instruments that we have now? BD: Does it give you satisfaction to know that

you have recorded all of them?

BD: Does it give you satisfaction to know that

you have recorded all of them?

BD: You had a work done here with the Chicago

Symphony...

BD: You had a work done here with the Chicago

Symphony... JMcC:

There’s a song cycle called Notturni ed

Alba, which is very personal to me. The Second Violin Concerto also has a strong

personal feeling for me. I’m thinking of works which I feel have a

particular personal commitment over and above happening to like them particularly.

The Third Symphony is a piece

I like very much, and I have a strong personal feeling for that piece, but

it’s not affiliated with my own personal life and associations and so on.

It’s just that I happen to be very fond of that piece on musical grounds.

I think it really does work, and there are one or two other symphonies, but

Notturni ed Alba is a very important

piece to me.

JMcC:

There’s a song cycle called Notturni ed

Alba, which is very personal to me. The Second Violin Concerto also has a strong

personal feeling for me. I’m thinking of works which I feel have a

particular personal commitment over and above happening to like them particularly.

The Third Symphony is a piece

I like very much, and I have a strong personal feeling for that piece, but

it’s not affiliated with my own personal life and associations and so on.

It’s just that I happen to be very fond of that piece on musical grounds.

I think it really does work, and there are one or two other symphonies, but

Notturni ed Alba is a very important

piece to me. JMcC: I often wonder about this, and I really

cannot come to any conclusion. I don’t think there is a balance.

A definition would say you draw this line, and on this side we’ve got entertainment,

and on this side we’ve got art, but then there are all sorts of pieces in

both. There are all sorts of borderline pieces. There are all

sorts of pieces which are one, all sorts which are the other, and some which

are both. I’m a little bit worried about the way classical music is

perceived by so many as being an elitist thing because it should not be an

elitist thing. Obviously, Webern is not going to become Top 20 material.

I enjoy Webern’s music very much, but I feel very worried when people talk

about Classical Music as if they rather distrusted selling it. I want

the biggest audience I can get, and I don’t care who they are! If

half the people in the world actually listened to my music and enjoyed it,

or at least have the opportunity of hearing it, and didn’t regard it

— because it’s classical — as being some

that’s not for them, then I would be a great deal happier. In Classical

Music, there are still a lot of people who have got almost a vested interest

in keeping it to themselves.

JMcC: I often wonder about this, and I really

cannot come to any conclusion. I don’t think there is a balance.

A definition would say you draw this line, and on this side we’ve got entertainment,

and on this side we’ve got art, but then there are all sorts of pieces in

both. There are all sorts of borderline pieces. There are all

sorts of pieces which are one, all sorts which are the other, and some which

are both. I’m a little bit worried about the way classical music is

perceived by so many as being an elitist thing because it should not be an

elitist thing. Obviously, Webern is not going to become Top 20 material.

I enjoy Webern’s music very much, but I feel very worried when people talk

about Classical Music as if they rather distrusted selling it. I want

the biggest audience I can get, and I don’t care who they are! If

half the people in the world actually listened to my music and enjoyed it,

or at least have the opportunity of hearing it, and didn’t regard it

— because it’s classical — as being some

that’s not for them, then I would be a great deal happier. In Classical

Music, there are still a lot of people who have got almost a vested interest

in keeping it to themselves.

JMcC:

It’s been given by High Schools and so on in England. It’s been on

quite a bit. It gets a production or two every year. I wish that

it had been taken up by an opera company for an Easter time show because I

think it would work if it were actually done by adults. It’s a pretty

tuneful piece.

JMcC:

It’s been given by High Schools and so on in England. It’s been on

quite a bit. It gets a production or two every year. I wish that

it had been taken up by an opera company for an Easter time show because I

think it would work if it were actually done by adults. It’s a pretty

tuneful piece. BD: Is this what makes a masterpiece

— that it will hold up after repeated performances?

BD: Is this what makes a masterpiece

— that it will hold up after repeated performances? BD: What is the lecture on?

BD: What is the lecture on? BD: [Looking at a page which has his official

titles] CBE, does that mean you’re a Sir?

BD: [Looking at a page which has his official

titles] CBE, does that mean you’re a Sir? JMcC: Yes, absolutely. The problems with

society are still there, but the piece enabled me to come to terms with

one thing at least.

JMcC: Yes, absolutely. The problems with

society are still there, but the piece enabled me to come to terms with

one thing at least.| Tannoy Ltd is a British manufacturer of loudspeakers and public-address systems. The company was founded by Guy Fountain in London, England, as Tulsemere Manufacturing Company in 1926, and moved to Coatbridge, Scotland, in the 1970s. Later on it was confirmed that the Coatbridge facility would be closed and all R&D and marketing developments would be relocated to Manchester and production would be moved to China. The term 'tannoy' is often used generically in colloquial English throughout the British Commonwealth to mean any public-address system, or even as a verb (to "tannoy"), particularly those used for announcements in public places. Although the word is a registered trademark, it has become a genericized trademark. The company's intellectual property department keeps a close eye on the media. To preserve its trademark, it often writes to publications that use its trade name without a capital letter or as a generic term for a PA system. |

BD: Nothing at all?

BD: Nothing at all? BD: Do you ever change things while you’re writing

because of the ensemble that’s going to perform it first?

BD: Do you ever change things while you’re writing

because of the ensemble that’s going to perform it first? JMcC: [Laughing] I hope so! Yes,

it seems to! Various ways of enriching people’s lives depend on what

kind of piece it is, who’s listening, and on what level they’re listening

to it. It depends whether they’re willing to come towards the composer

and say, “Let me hear what you have to say. I’ll

try and listen to it and try and take part in it.”

Music belongs as much to the audience in one sense as it does to anybody else,

and that sense is that the audience becomes part of it. This is less

true of listening to records than it is of live performance.

JMcC: [Laughing] I hope so! Yes,

it seems to! Various ways of enriching people’s lives depend on what

kind of piece it is, who’s listening, and on what level they’re listening

to it. It depends whether they’re willing to come towards the composer

and say, “Let me hear what you have to say. I’ll

try and listen to it and try and take part in it.”

Music belongs as much to the audience in one sense as it does to anybody else,

and that sense is that the audience becomes part of it. This is less

true of listening to records than it is of live performance.  BD:

To go back to composing?

BD:

To go back to composing? BD: Here you just ‘click, click’ and put in new

one, and then it’s done.

BD: Here you just ‘click, click’ and put in new

one, and then it’s done. JMcC: Oh yes, yes. But you see I’m trying

to do that by playing music that I love, or find exciting — even

if it is a piece which is brand new, like a first performance. I haven’t

actually given that many first performances, come to think of it, because

I haven’t been particularly bothered whether it was a first performance or

not. I want to like the music I want to play, and I want to share that

knowledge of the piece with people, and I like introducing people to repertoire

that they might not know. That’s also very important. There

are all sorts of very well-known composers who wrote some splendid pieces

which are never played — Schumann’s Intermezzi, for example. It probably

pops up very occasionally, but it doesn’t appear on the big recitals series

much.

JMcC: Oh yes, yes. But you see I’m trying

to do that by playing music that I love, or find exciting — even

if it is a piece which is brand new, like a first performance. I haven’t

actually given that many first performances, come to think of it, because

I haven’t been particularly bothered whether it was a first performance or

not. I want to like the music I want to play, and I want to share that

knowledge of the piece with people, and I like introducing people to repertoire

that they might not know. That’s also very important. There

are all sorts of very well-known composers who wrote some splendid pieces

which are never played — Schumann’s Intermezzi, for example. It probably

pops up very occasionally, but it doesn’t appear on the big recitals series

much.

BD:

Have you ever thought about playing fortepiano?

BD:

Have you ever thought about playing fortepiano?| Josef Mysliveček (9 March 1737

– 4 February 1781) was a Czech composer who contributed to the formation of

late eighteenth-century classicism in music. Mysliveček provided his younger

friend Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart with significant compositional models in

the genres of symphony, Italian serious opera, and violin concerto; both

Wolfgang and his father Leopold Mozart considered him an intimate friend

from the time of their first meetings in Bologna in 1770 until he betrayed

their trust over the promise of an operatic commission for Wolfgang to be

arranged with the management of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples. He was close

to the Mozart family, and there are frequent references to him in the Mozart

correspondence. |

BD:

You’re about to hit 60.

BD:

You’re about to hit 60. JMcC: Alan Rawsthorne lived from 1905 to 1971,

and was born in a little wool town north of Manchester. When he died

he was highly regarded. He wasn’t a major figure in the way that Britten

and Walton were, but he was regarded as a very distinguished composer, and

he had had a number of very popular works. His Second Piano Concerto of 1951 had actually

been performed 100 times in the first two years, and was very popular at

one time. He came to prominence in the 1930s, and he wrote in a style

that is very chromatic. It changes key. Actually, it doesn’t have

keys; it has tonal center, a key center of a traditional key, and it is constantly

changing, which makes the music rather illusive. I’ve always loved

his music ever since I was a child, and when I was ten, I met him for the

first time. I studied piano with Gordon Green for seventeen years,

from the age of eight to twenty-five. He was in Liverpool and had been

a fellow student of Alan’s at the Royal Manchester College of Music

— as it then was called — in the 1920s.

So when Rawsthorne had a piece done in Liverpool, he would come and stay

with Gordon. I lived just around the corner, so was bound to meet him.

I was already a fan of his music, and we became friends. I wouldn’t

claim that I was a close friend. He had a number of close friends.

He was a very reserved man. He was extremely funny. He was one

of the wittiest people you could ever meet, and very generous. He never

— or hardly ever — said a bad word about any other

composer. He really was not at all bitchy about other composers.

He did drink too much. That was his great problem. He drank

an enormous amount, which killed him actually, but his reputation dipped

partly because his music did fall into mannerism. Occasionally he

would produce a rather duff piece because he was possibly drinking too much.

The energy just wasn’t there. I’ve just written a book about him, which

I’m very pleased to have done because it was a labor of love. It wasn’t

just a commercial enterprise. I’ve played a lot of his music over the

years. I’ve probably played about twelve pieces, mostly instrumental

music. There are some vocal pieces. There is a marvelous piece

for soprano, chorus and orchestra called Carmen Vitale, which is quite a late piece,

and he wrote a lot of film music. For me the great golden age of film

music was in the 1940s and early ‘50s in England. I know people who’d

be shocked at that, but I think that was the great golden age because people

like Walton and Malcolm Arnold came in towards the end of that period with

some of their best work. Vaughan Williams’ Scott of the Antarctic music is a wonderful

score, with such subtle understanding of the psychology of the whole thing,

and the relationship between man and the environment. It’s all there

in the score, and Alan did write a number of very, very fine film scores.

The Cruel Sea was one. Bernard

Herrmann, the great Hollywood composer, used to say that Uncle Silas, which was one of Alan’s films,

was one of the very greatest film scores ever written.

JMcC: Alan Rawsthorne lived from 1905 to 1971,

and was born in a little wool town north of Manchester. When he died

he was highly regarded. He wasn’t a major figure in the way that Britten

and Walton were, but he was regarded as a very distinguished composer, and

he had had a number of very popular works. His Second Piano Concerto of 1951 had actually

been performed 100 times in the first two years, and was very popular at

one time. He came to prominence in the 1930s, and he wrote in a style

that is very chromatic. It changes key. Actually, it doesn’t have

keys; it has tonal center, a key center of a traditional key, and it is constantly

changing, which makes the music rather illusive. I’ve always loved

his music ever since I was a child, and when I was ten, I met him for the

first time. I studied piano with Gordon Green for seventeen years,

from the age of eight to twenty-five. He was in Liverpool and had been

a fellow student of Alan’s at the Royal Manchester College of Music

— as it then was called — in the 1920s.

So when Rawsthorne had a piece done in Liverpool, he would come and stay

with Gordon. I lived just around the corner, so was bound to meet him.

I was already a fan of his music, and we became friends. I wouldn’t

claim that I was a close friend. He had a number of close friends.

He was a very reserved man. He was extremely funny. He was one

of the wittiest people you could ever meet, and very generous. He never

— or hardly ever — said a bad word about any other

composer. He really was not at all bitchy about other composers.

He did drink too much. That was his great problem. He drank

an enormous amount, which killed him actually, but his reputation dipped

partly because his music did fall into mannerism. Occasionally he

would produce a rather duff piece because he was possibly drinking too much.

The energy just wasn’t there. I’ve just written a book about him, which

I’m very pleased to have done because it was a labor of love. It wasn’t

just a commercial enterprise. I’ve played a lot of his music over the

years. I’ve probably played about twelve pieces, mostly instrumental

music. There are some vocal pieces. There is a marvelous piece

for soprano, chorus and orchestra called Carmen Vitale, which is quite a late piece,

and he wrote a lot of film music. For me the great golden age of film

music was in the 1940s and early ‘50s in England. I know people who’d

be shocked at that, but I think that was the great golden age because people

like Walton and Malcolm Arnold came in towards the end of that period with

some of their best work. Vaughan Williams’ Scott of the Antarctic music is a wonderful

score, with such subtle understanding of the psychology of the whole thing,

and the relationship between man and the environment. It’s all there

in the score, and Alan did write a number of very, very fine film scores.

The Cruel Sea was one. Bernard

Herrmann, the great Hollywood composer, used to say that Uncle Silas, which was one of Alan’s films,

was one of the very greatest film scores ever written. JMcC: [Laughs] What does he know, yes!

He wasn’t somebody who’d say a great deal at a performance... except on one

occasion when he was in the rehearsal for an orchestral piece. The

orchestra played the piece through, and the conductor turned round and said,

“Is Mr. Rawsthorne here?”

He looked around the hall, and Alan put his hand up rather shyly and said,

“Yes, I’m here.” The conductor

said, “Mr. Rawsthorne, is there anything you’d like

to say?” and Alan said, “Well,

I don’t think so, except possibly could you possibly play it a bit better

next time!” [Both laugh] So it must have

been pretty bad because he normally wasn’t as blunt as that! He was

very helpful. He was a marvelous pianist at one time. He studied

in the 1930s in Poland with Egon Petri, so he was good enough to study with

one of the great pianists and teachers.

JMcC: [Laughs] What does he know, yes!

He wasn’t somebody who’d say a great deal at a performance... except on one

occasion when he was in the rehearsal for an orchestral piece. The

orchestra played the piece through, and the conductor turned round and said,

“Is Mr. Rawsthorne here?”

He looked around the hall, and Alan put his hand up rather shyly and said,

“Yes, I’m here.” The conductor

said, “Mr. Rawsthorne, is there anything you’d like

to say?” and Alan said, “Well,

I don’t think so, except possibly could you possibly play it a bit better

next time!” [Both laugh] So it must have

been pretty bad because he normally wasn’t as blunt as that! He was

very helpful. He was a marvelous pianist at one time. He studied

in the 1930s in Poland with Egon Petri, so he was good enough to study with

one of the great pianists and teachers. JMcC:

I have to, yes.

JMcC:

I have to, yes. JMcC:

I do work very hard. I don’t get enough holidays. On the other

hand — and I think this is very important

— I have a lot of non-musical interests which I pursue at home,

such as listening to cricket or watching it on television. I very seldom

even manage to get to a cricket match. I enjoy watching golf on television,

and I enjoy watching Wimbledon. I find most tennis tournaments rather

boring these days, but Wimbledon I still like because it’s on grass.

Do you know snooker?

JMcC:

I do work very hard. I don’t get enough holidays. On the other

hand — and I think this is very important

— I have a lot of non-musical interests which I pursue at home,

such as listening to cricket or watching it on television. I very seldom

even manage to get to a cricket match. I enjoy watching golf on television,

and I enjoy watching Wimbledon. I find most tennis tournaments rather

boring these days, but Wimbledon I still like because it’s on grass.

Do you know snooker?John McCabe, composer - obituary [The Telegraph, 6:15PM GMT 13 Feb 2015] [Text only - photos and links added for this website presentation] Composer-pianist in the tradition of Bartók and Rachmaninov, who drew inspiration from art and literature John McCabe, who has died aged 75, was a prolific composer, a formidable pianist and an enthusiastic administrator. He was, wrote Michael Kennedy, a man of his time, who in his composition flirted with serialism, drew inspiration from rock and jazz, and latterly nodded in the direction of minimalism. The public knew his virtuosic keyboard work (a recording of Haydn’s piano sonatas brought acclaim), while the cognoscenti recognised his distinctive style – “a mix of Vaughan Williams, Britten and Tippett leavened with Karl Amadeus Hartmann and serial procedures”, the critic Guy Rickards noted. In truth the performance and the composition fed each other. He was, said Gramophone, a musician in the composer-pianist tradition of Bartók and Rachmaninov. There were few areas in which this musical polymath was not influential: he composed the theme for the 1970s ITV series Sam, lectured on Webern’s piano music and gave the British premiere of John Corigliano’s Piano Concerto. He wrote musical criticism and published guides to composers as diverse as Haydn and Alan Rawsthorne, his fellow Northerner. There were also academic posts, including principal of the London College of Music from 1983 to 1990. McCabe’s influences were many. Gaudí and Mosaic, two of his piano studies, were inspired by Catalan architecture and Islamic art respectively. His third string quartet took its inspiration from the landscape around Ullswater, and his fifth from illustrations of bees by Graham Sutherland. He also wrote for individuals: a dissonant flute concerto for James Galway (1990), for example, and for the pianist Barry Douglas a meditation on mortality called Tenebrae. McCabe argued that the music of other English composers should be heard more often. “Why do we have to wait until Walton’s 75th birthday to hear his overtures?” he demanded. “Why do we not hear more Vaughan Williams?”

John McCabe was born at Huyton, on Merseyside, on April 21 1939, the son of a Scottish-Irish research physicist. His mother, who claimed multiple European ancestries, was a talented violinist. Badly burnt in a fire, John missed his early schooling – time he spent listening to records, learning the piano and writing 13 symphonies, which he later destroyed. At Liverpool Institute, where he played the cello (“very badly – I was the principal and at times the only cellist in the school orchestra”), he was a contemporary of Paul McCartney and George Harrison. He yearned to be a cricketer but “I never even made the school 11”, although he became a walking encyclopedia on the sport and often composed with it playing on the television. At the University of Manchester he was reputedly expelled from Humphrey Procter-Gregg’s class after playing his own music in a recital. He then studied at the Royal Manchester College of Music, followed by a year in Munich with Harald Genzmer, a pupil of Hindemith. Meanwhile, the Hallé Orchestra premiered his Violin Concerto (Martin Milner was the soloist), while in November 1962 he gave the first London performance of Elliott Carter’s Piano Sonata, “giving the impression of grasping [its] shape and sense of direction”, one critic wrote. In 1965 he joined the University of Wales as pianist in residence for three years. His First Symphony, subtitled Elegy and influenced by jazz, was commissioned by the Hallé and premiered at the Cheltenham Festival in 1966 under John Barbirolli. Notturni ed Alba, a setting of Latin texts for soprano and orchestra brimming with vocal virtuosity, was heard at the Three Choirs Festival in 1970 and brought McCabe to wider attention. He also created an enchanting children’s opera from C S Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. McCabe the pianist was now touring extensively, once performing five different programmes on five nights in five cities across North America. “I was wandering around airports in a daze,” he recalled. He began his Haydn marathon for Decca in 1975, and two years later still found pleasure in the composer’s music. “Even the simplest [sonatas] have tremendous variety and riches,” he said, and as if to prove a point wrote his own Haydn Variations in 1983. Unwilling to be pigeon-holed, he then recorded Hindemith’s fiendish Ludus tonalis for Hyperion in 1996.

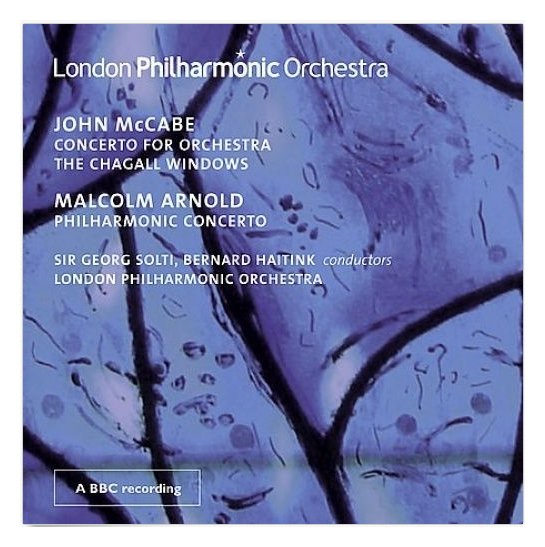

In the mid-1970s McCabe dropped serialism – even though he had used it brilliantly in The Chagall Windows (1974), a 30-minute tone poem – and adopted a more melodic approach. International acclaim came in 1982 when Georg Solti championed his Concerto for Orchestra in Chicago. By the late 1990s ballet had come to the fore, with works such as King Arthur for Birmingham Royal Ballet. His last work was Christ’s Nativity, a setting of 17th-century poetry by Henry Vaughan for the Hallé Choir premiered in Manchester two months ago. McCabe, who was appointed CBE in 1985, is survived by his wife Monica Smith, whom he married in 1974. John McCabe, born April 21, 1939, died February 13, 2015 |

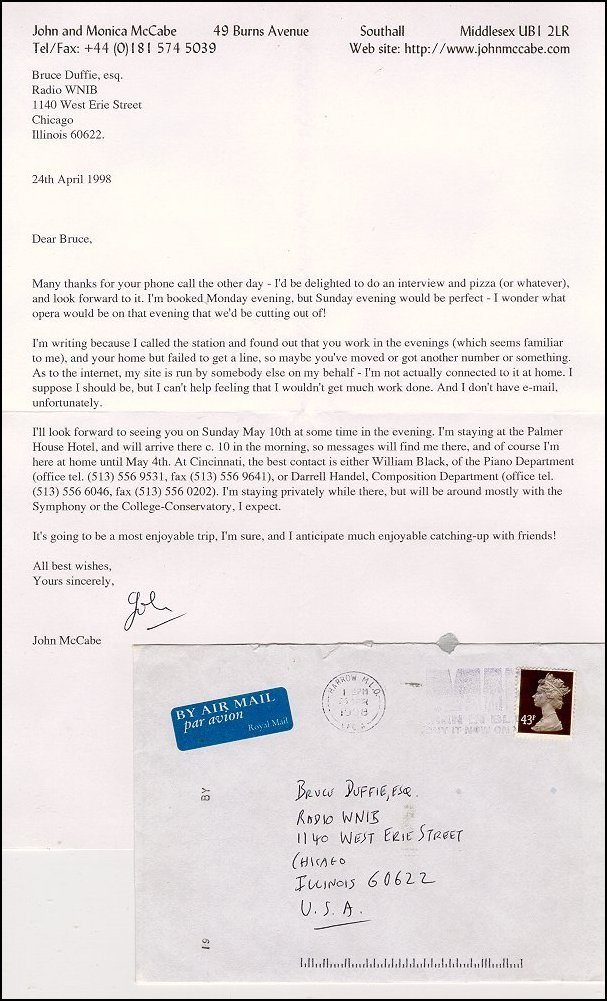

© 1986 & 1998 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on October 6, 1986, and May 10, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1989, 1990, 1994, and 1999; and on WNUR in 2006 and 2012; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2007 and 2015. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.