A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

|

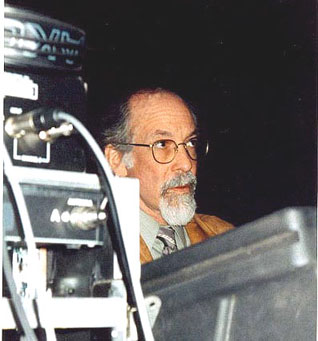

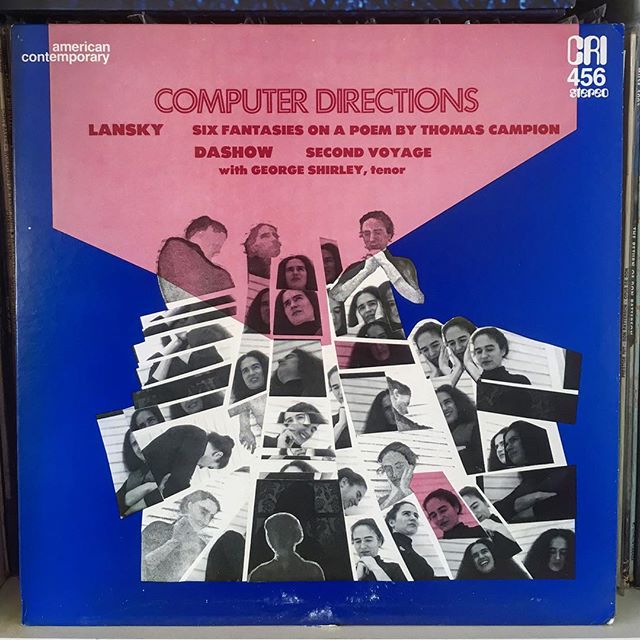

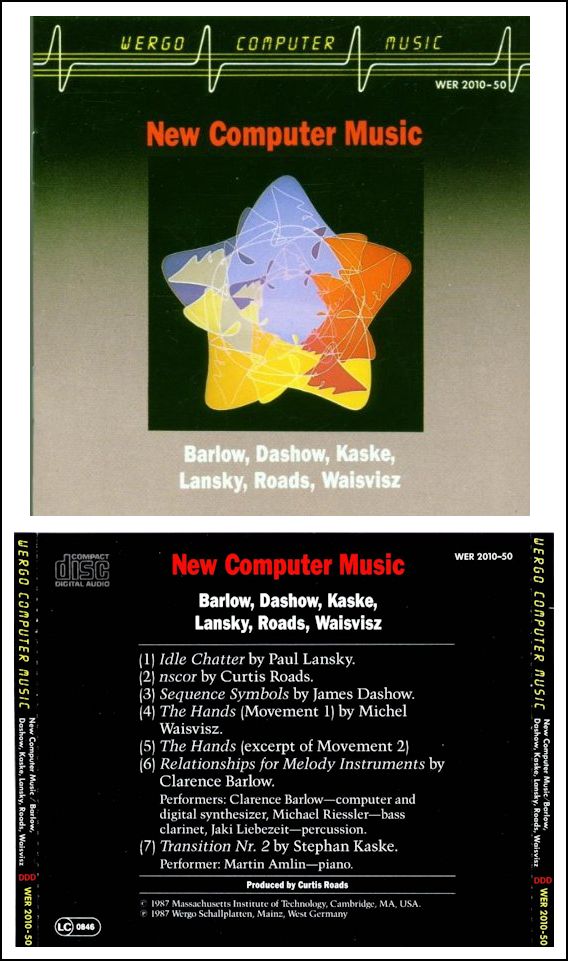

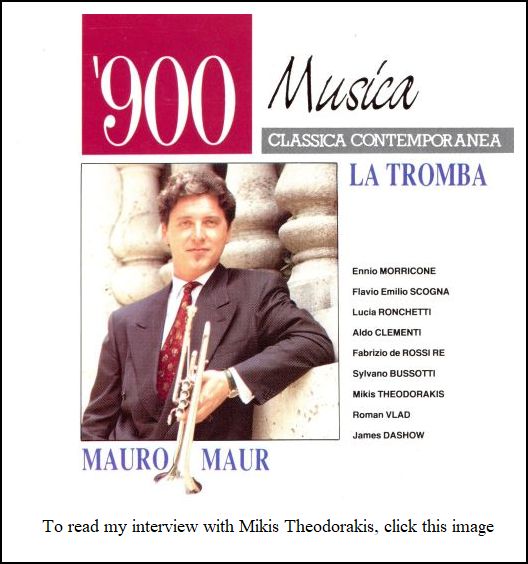

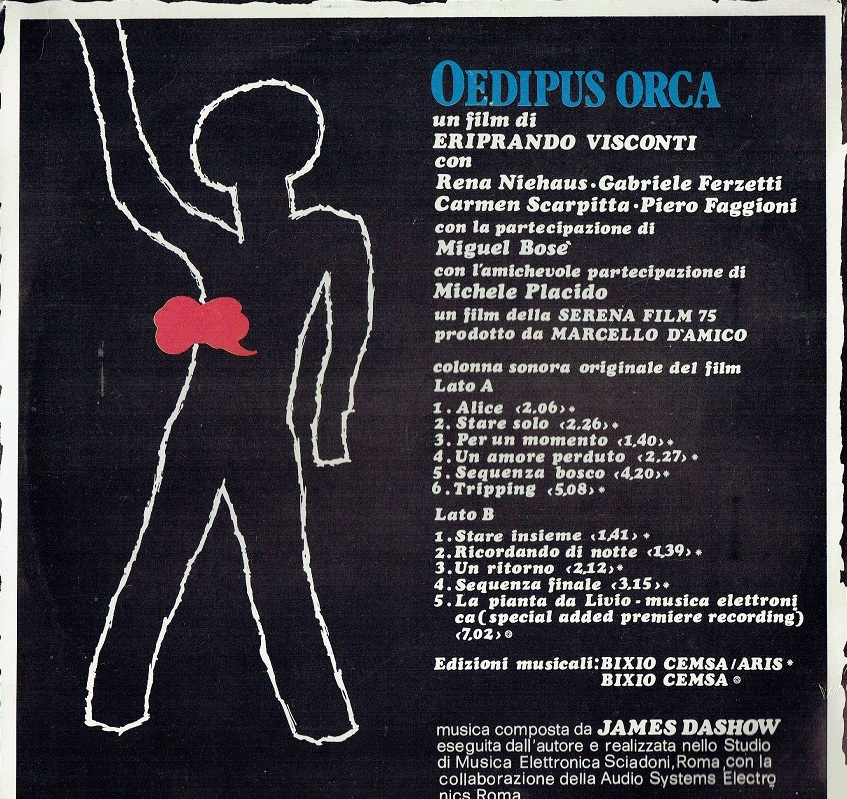

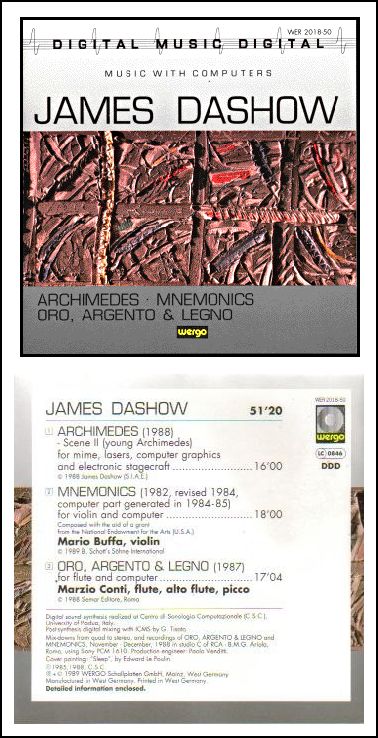

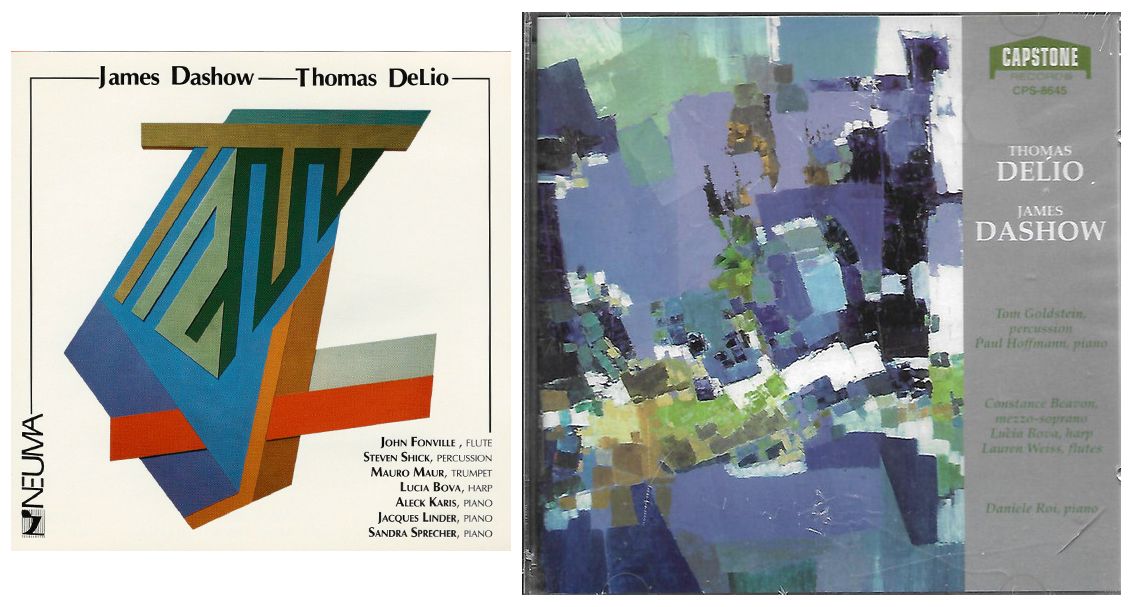

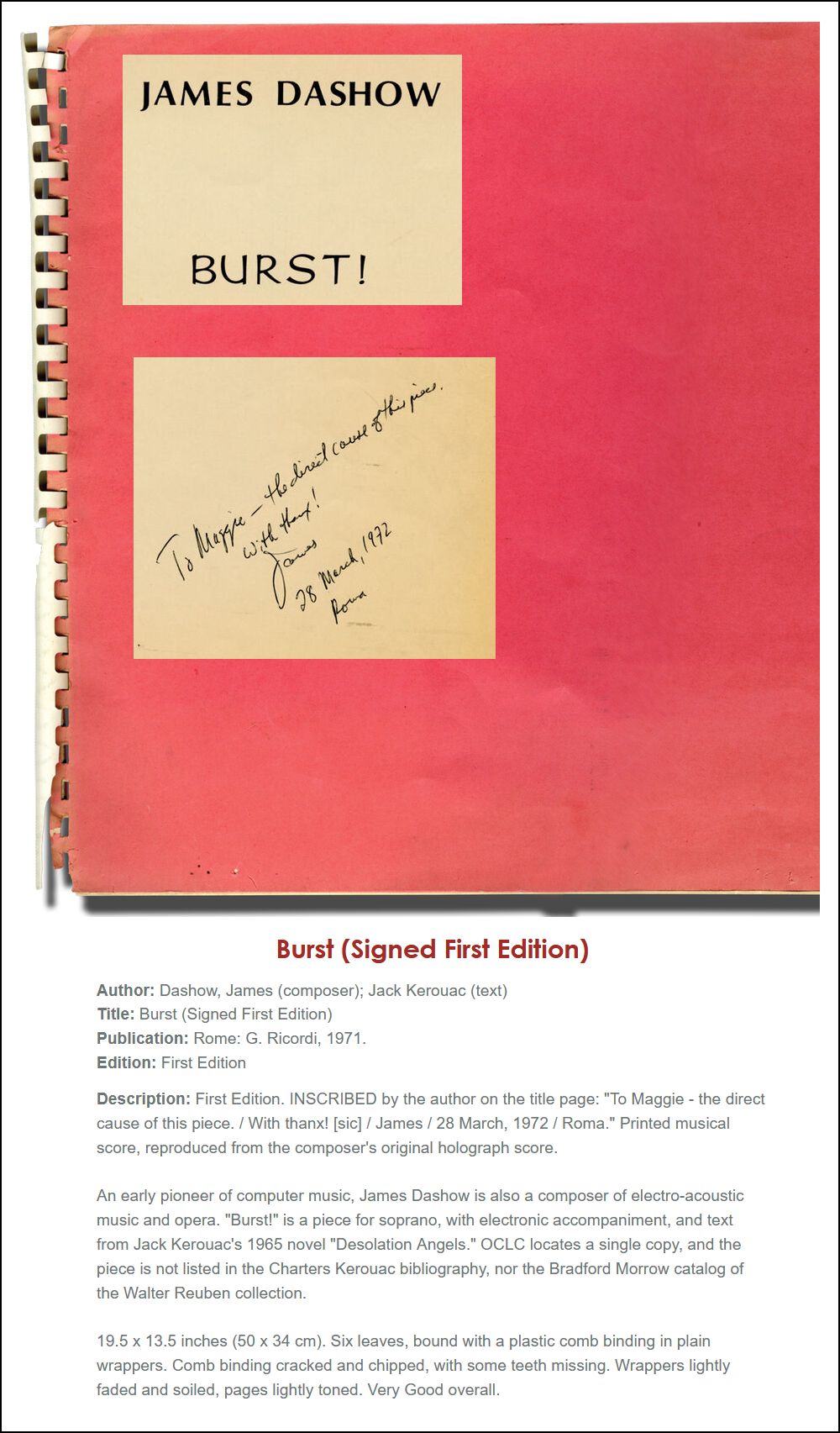

James Dashow was born on November 7, 1944, outside of Chicago. His musical studies began in high school with Horace Reisberg. His principal teachers at the university level were J. K. Randall, Arthur Berger and Seymour Shifrin. In 1969, Dashow went to Italy on a Fulbright Fellowship to complete his studies with Goffredo Petrassi. For many years, he studied the music of Luigi Dallapiccola independently. One of the first to compose music for digital audio synthesis (“computer music”), Dashow was invited by Graziano (Giuliano) Tisato to work at the computer center of the University of Padova, where he created the first computer music compositions in Italy. He was the first vice president of the International Computer Music Association, has taught at MIT and Princeton University, and continues to actively hold master classes, lectures and concerts in Europe and North America. In 2003 he was composer-in-residence at the 12th Annual Florida Electroacoustic Music Festival in Gainesville, Florida. For several years he and Riccardo Bianchini coproduced a weekly contemporary music program for RAI. He is the author of the MUSIC30 language for digital sound synthesis, and invented the Dyad System, a method that both integrates pitch structure based on dyads into electronic sounds, as well as develops the pitch structure itself in terms of dyadic elaborations. Following on his extensive use of audio spatialization as an integral part of the compositional process, Dashow composed the first opera designed to be performed in a Planetarium (ARCHIMEDES), taking advantage of the depth projection capabilities of the digital planetarium projectors, and the multichannel audio systems that together provide a full immersion theatrical experience. He continues to develop the idea of a double approach to spatialization, through the complementary concepts of Movement IN Space, and Movement OF Space. His most important recognitions include the Prix Magistere at Bourges

in 2000, Guggenheim (1989) and Koussevitzky (1998) Foundation grants,

and in 2011 the Fondazione CEMAT distinguished career award “Il CEMAT

per la Musica” in recognition of his outstanding contributions to electro-acoustic

music. Awards and recognition

-- Names which are links in this box and below

refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

James Dashow: [Sighs] This is not so much what

I perceive in the United States, because, as you know, I’ve been

living in Italy for twenty-five years. The situation in Italy,

recently, has gotten rather, shall we say, unfortunate because of extreme

cuts in possibilities of earning a living as a composer. The royalties

have been cut significantly by the state royalty agency, as well

as the radio broadcasting, which means considerably less time for

contemporary music. This is because of a shake-up within the

national radio, and because of the political situation in Italy, which

has taken a sudden turn to the right.

James Dashow: [Sighs] This is not so much what

I perceive in the United States, because, as you know, I’ve been

living in Italy for twenty-five years. The situation in Italy,

recently, has gotten rather, shall we say, unfortunate because of extreme

cuts in possibilities of earning a living as a composer. The royalties

have been cut significantly by the state royalty agency, as well

as the radio broadcasting, which means considerably less time for

contemporary music. This is because of a shake-up within the

national radio, and because of the political situation in Italy, which

has taken a sudden turn to the right. BD: [Being serious] Would you

compose differently if you were starving in a garret?

BD: [Being serious] Would you

compose differently if you were starving in a garret? JD: That can happen. In fact,

one should have the courage to say you don’t what is behind the piece.

Does the piece work, should be the major question. By and large,

to make a piece work you do have to know something. But, it’s

like the question of whether a million monkeys can turn out Shakespeare

after a while. That’s entirely possible. If you get Shakespeare

from one of those monkeys, are you going to complain that it was

a monkey that did it?

JD: That can happen. In fact,

one should have the courage to say you don’t what is behind the piece.

Does the piece work, should be the major question. By and large,

to make a piece work you do have to know something. But, it’s

like the question of whether a million monkeys can turn out Shakespeare

after a while. That’s entirely possible. If you get Shakespeare

from one of those monkeys, are you going to complain that it was

a monkey that did it? BD: Do you still meet resistance among the audience

towards electronic pieces?

BD: Do you still meet resistance among the audience

towards electronic pieces? JD: Particularly American, and the

more I make my way in my work, I realize that I live in Italy. I’ve

been there for twenty-five years, and probably will be there for

another thirty-five years, but I’ll always be eighty per cent an

American composer. Americans have a sense of rhythm, regular

or irregular. I don’t mean rhythm in the sense of a steady tempo.

I mean a conception of rhythm which is very much jazz-derived. I

grew up in the Chicago area playing jazz for the first twenty years of

my life.

JD: Particularly American, and the

more I make my way in my work, I realize that I live in Italy. I’ve

been there for twenty-five years, and probably will be there for

another thirty-five years, but I’ll always be eighty per cent an

American composer. Americans have a sense of rhythm, regular

or irregular. I don’t mean rhythm in the sense of a steady tempo.

I mean a conception of rhythm which is very much jazz-derived. I

grew up in the Chicago area playing jazz for the first twenty years of

my life. BD: Are you basically pleased

with the music you’ve turned out over the years?

BD: Are you basically pleased

with the music you’ve turned out over the years? JD: Generally, one piece at a time,

although one piece will have spin-offs into other pieces. For

example, I just finished the Septet that was commissioned by the

Fromm Foundation. In the meantime, I’d had a request from a very

good composer/conductor friend of mine in Rome, named Flavio Emilio Scogna

(1956- ), for an orchestra piece. I found myself, all of sudden,

beginning to get orchestral ideas while I was writing my Septet.

I maintain a little notebook on the side, and started doing some

sketches for that. In the meantime, I’d also had a request from

a contrabass player for a piece for contrabass and computer, so when that

was in my head, I began every now and then getting a contrabass idea,

which, since the Septet doesn’t have a contrabass in it, I realized

I was also working on that other piece. But as far as actually composing

is concerned, I’m dedicated to one piece, although quite often I turn

out enough material for one piece that’s good for at least two other pieces.

JD: Generally, one piece at a time,

although one piece will have spin-offs into other pieces. For

example, I just finished the Septet that was commissioned by the

Fromm Foundation. In the meantime, I’d had a request from a very

good composer/conductor friend of mine in Rome, named Flavio Emilio Scogna

(1956- ), for an orchestra piece. I found myself, all of sudden,

beginning to get orchestral ideas while I was writing my Septet.

I maintain a little notebook on the side, and started doing some

sketches for that. In the meantime, I’d also had a request from

a contrabass player for a piece for contrabass and computer, so when that

was in my head, I began every now and then getting a contrabass idea,

which, since the Septet doesn’t have a contrabass in it, I realized

I was also working on that other piece. But as far as actually composing

is concerned, I’m dedicated to one piece, although quite often I turn

out enough material for one piece that’s good for at least two other pieces.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on September 19, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB two months later, and again in 1995 and 1999. A copy of the unedited audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made in 2019, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.