A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

BD: Musicians who are performing, or musicians who

are listening?

BD: Musicians who are performing, or musicians who

are listening?

BD: Is this your own in-house performing company?

BD: Is this your own in-house performing company? ES:

[Sighs] You keep asking questions that have essentially no meaning

to me! Just last night I copied a tape of a quartet for flute

and strings that our Artistic Director will take to Europe with him as one

of the examples of what we do, just to see if he can foment some activity

there. I was, myself, simply enchanted through the whole piece.

It’s one of the things that pleases me most. It seemed to me that it

was doing awfully pleasant things all the time, and doing little witty, cheerful,

pretty things down in the accompaniment, while the tune was a nice thing

going on. Yet it is as carefully and scrupulously written as anything

else I’ve done. You tell me where the balance is. You tell me

where that is in the Appassionata Sonata

or the Ninth Symphony, and I will

try to answer it about my music! [Both laugh]

ES:

[Sighs] You keep asking questions that have essentially no meaning

to me! Just last night I copied a tape of a quartet for flute

and strings that our Artistic Director will take to Europe with him as one

of the examples of what we do, just to see if he can foment some activity

there. I was, myself, simply enchanted through the whole piece.

It’s one of the things that pleases me most. It seemed to me that it

was doing awfully pleasant things all the time, and doing little witty, cheerful,

pretty things down in the accompaniment, while the tune was a nice thing

going on. Yet it is as carefully and scrupulously written as anything

else I’ve done. You tell me where the balance is. You tell me

where that is in the Appassionata Sonata

or the Ninth Symphony, and I will

try to answer it about my music! [Both laugh] BD: Do you ever go back and tamper with your

scores, and perhaps make them a little bit easier?

BD: Do you ever go back and tamper with your

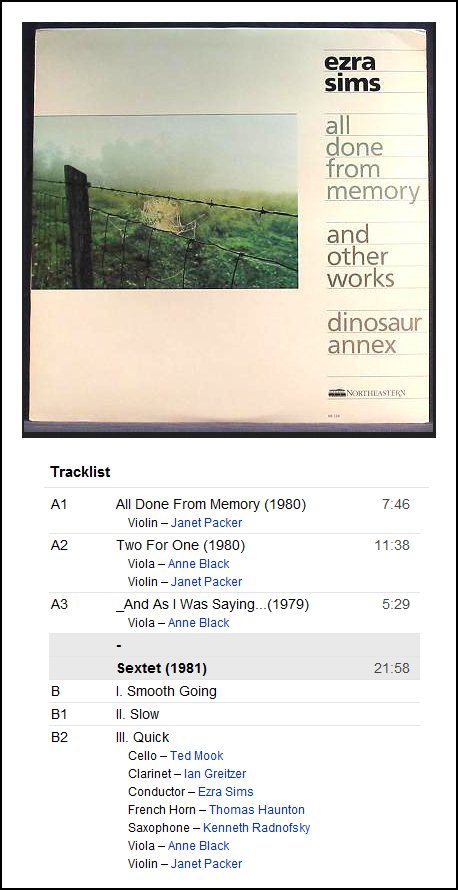

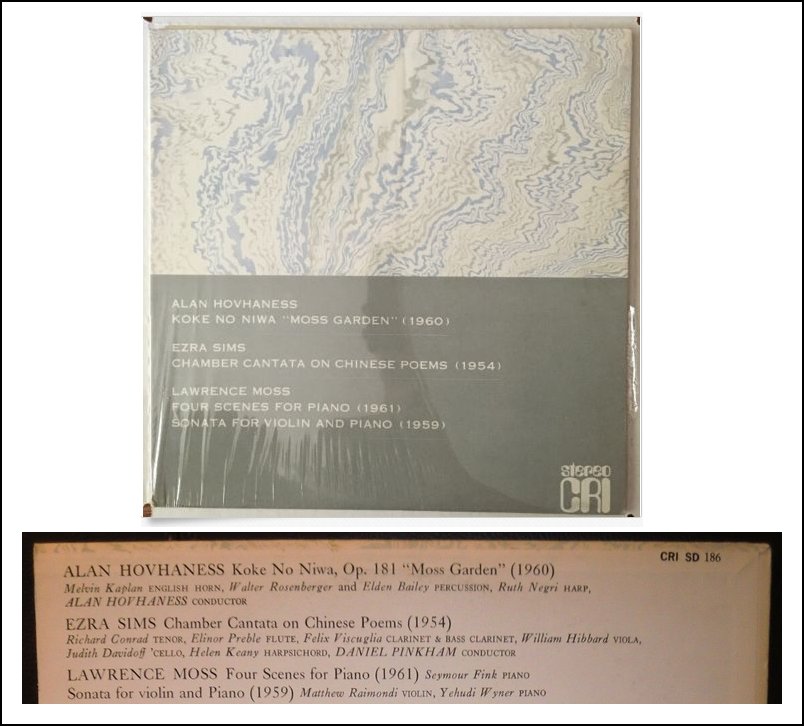

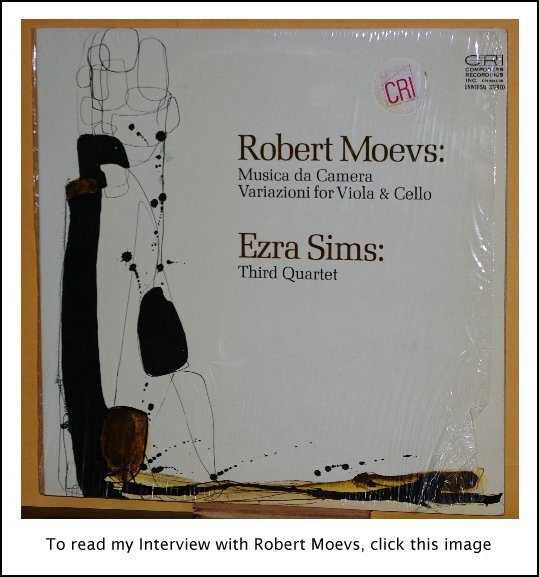

scores, and perhaps make them a little bit easier? BD: On CRI?

BD: On CRI? ES: Get it right! I wish I really felt I knew

enough about all of this. I guess if I took on a composition student,

I’d do one or two things. Either take them through all the techniques

and make certain that they’re competent in all the new, twentieth century

ones, or else, as Milhaud did for us at Mills, just make them play through

the pieces and make my comments. I would, perhaps in certain cases,

advise them to stay freelance and in other cases advise them to go out and

get themselves into a teaching position in a school as fast as they could.

It would depend on the student, but certainly what would come through would

be my sense that having been a well brought up and nicely behaved young man,

I believed what my seniors told me a little too much.

ES: Get it right! I wish I really felt I knew

enough about all of this. I guess if I took on a composition student,

I’d do one or two things. Either take them through all the techniques

and make certain that they’re competent in all the new, twentieth century

ones, or else, as Milhaud did for us at Mills, just make them play through

the pieces and make my comments. I would, perhaps in certain cases,

advise them to stay freelance and in other cases advise them to go out and

get themselves into a teaching position in a school as fast as they could.

It would depend on the student, but certainly what would come through would

be my sense that having been a well brought up and nicely behaved young man,

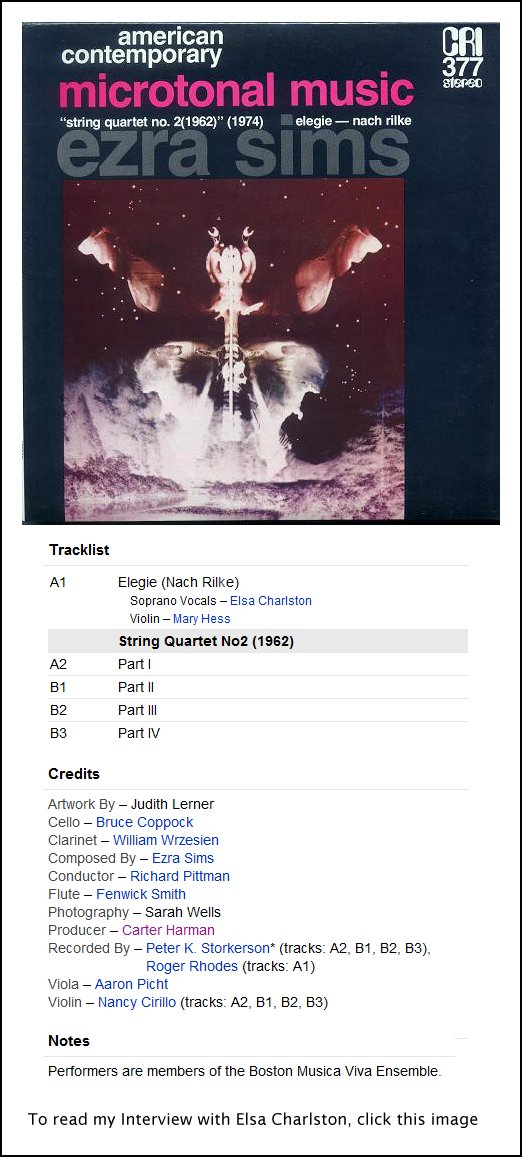

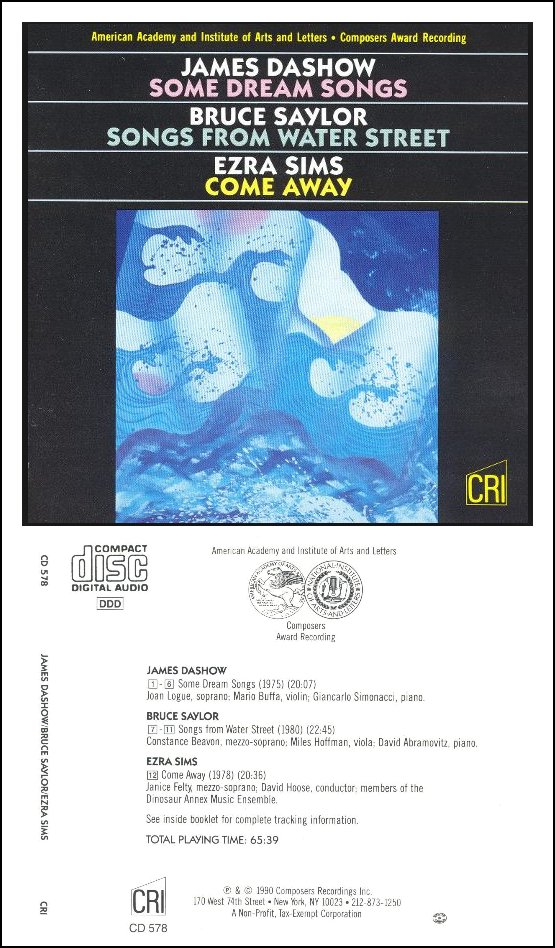

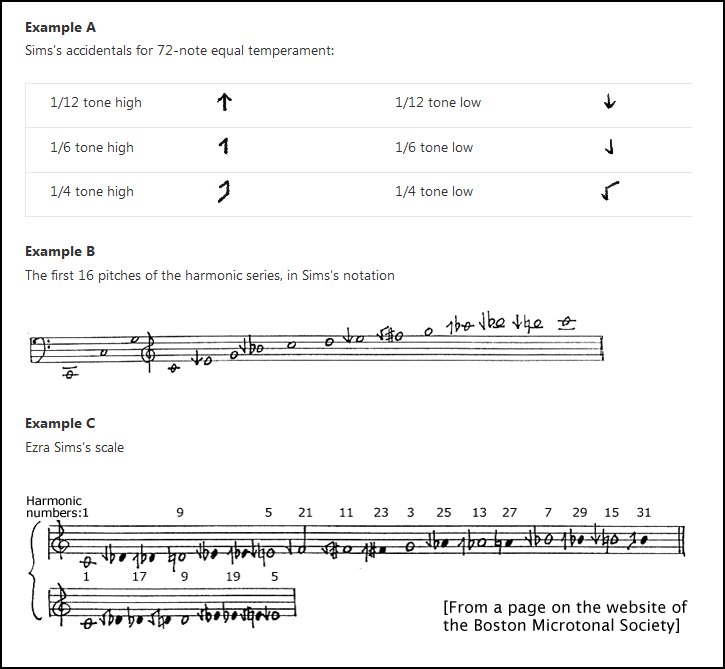

I believed what my seniors told me a little too much. Ezra Sims was educated at Yale University and Mills College, where he studied with Quincy Porter and Darius Milhaud, respectively. Since 1958 he has lived and composed in Cambridge, Mass., tapping into the Boston area’s musical resources. He is known mainly as a composer of microtonal music. He made his professional debut (with his earlier twelve-note music) on a Composers Forum program, in New York, in 1959. In 1960, he found himself compelled by his ear to begin writing microtonal music, which he has done almost exclusively since then — aside from several years when he made tape music for dancers, musicians at the time being generally even more afraid of microtones than they are now. His music has been performed from Tokyo to Salzburg. In 1976 he co-founded the Dinosaur Annex Ensemble with Rodney Lister and Scott Wheeler. Sims’ microtonal notational system has become the standard for Boston’s unusually high number of composers and performers using seventy-two notes. (Most of the Dinosaur Annex musicians are fluent with it, and Joe Maneri uses it, as does everyone who passes through Maneri’s course at the New England Conservatory. Also, cellist Ted Mook has created a font for Sims' microtonal symbols.

He has received

various awards — Guggenheim Fellowship, Koussevitzky commission, American

Academy of Arts and Letters Award, etc. He has

lectured on his music in the US and abroad, most notably at the Hambürger

Musikgespräch, 1994; the second Naturton Symposium in Heidelberg, 1992;

and the 3rd and 4th Symposium, Mikrotöne und Ekmelische

Musik, at the Hochschüle für Musik und Darstellende Kunst

Mozarteum, Salzburg, in 1989 & 1991. In 1992-93,

he was guest lecturer in the Richter Herf Institut für Musikalische

Grundlagenforschung in the Mozarteum |

This interview was recorded on the telephone on June 6, 1987.

Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB the following January,

and again in 1993 and 1998. A copy of the unedited audio tape was placed

in the Archive of Contemporary Music

at Northwestern University.

This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2010.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.