| Constance

Beavon, mezzo soprano, has performed the lyric mezzo soprano operatic repertory

with New York City Opera (Cavallaria Rusticana and others),

Grand Théâtre du Genève (Il Turco in Italia),

Chicago Opera Theater (Where the Wild Things Are), Harrisburg

Symphony (L'Enfant et les Sortileges), Clarion Concerts (Lodoiska)

and Mannes Opera (Così Fan Tutte) as well as numerous world

premiere operas for After Dinner Opera, Music Downtown, League ISCM, Aviva

Players and Musica Viva of New York. Performances as soloist with the symphony orchestras of Houston, Montreal, Baltimore, Arkansas, New Jersey, University of Chicago, New Orchestra of Westchester, Maine Music Society, Musica Viva of New York, Queens College, Du Page and Fox Valley have included masterpieces of the orchestral song repertoire including Mahler Fourth Symphony, Das Lied von der Erde, Ruckert Lieder and Kindertotenlieder, Ravel Sheherezade, Chausson Poème de l'Amour et de la Mer, Canteloube Songs of the Auvergne, and Barber Knoxville: Summer of 1915. Ms. Beavon has performed the oratorio repertoire from Handel's Messiah to Beethoven's Ninth Symphony at Lincoln Center, Carnegie Hall and throughout the United States, and created more than a dozen new orchestral sacred works with Incontri di Musica Sacra e Contmporanea in performances throughout Italy and with the Harare Symphony in Zimbabwe, Africa.

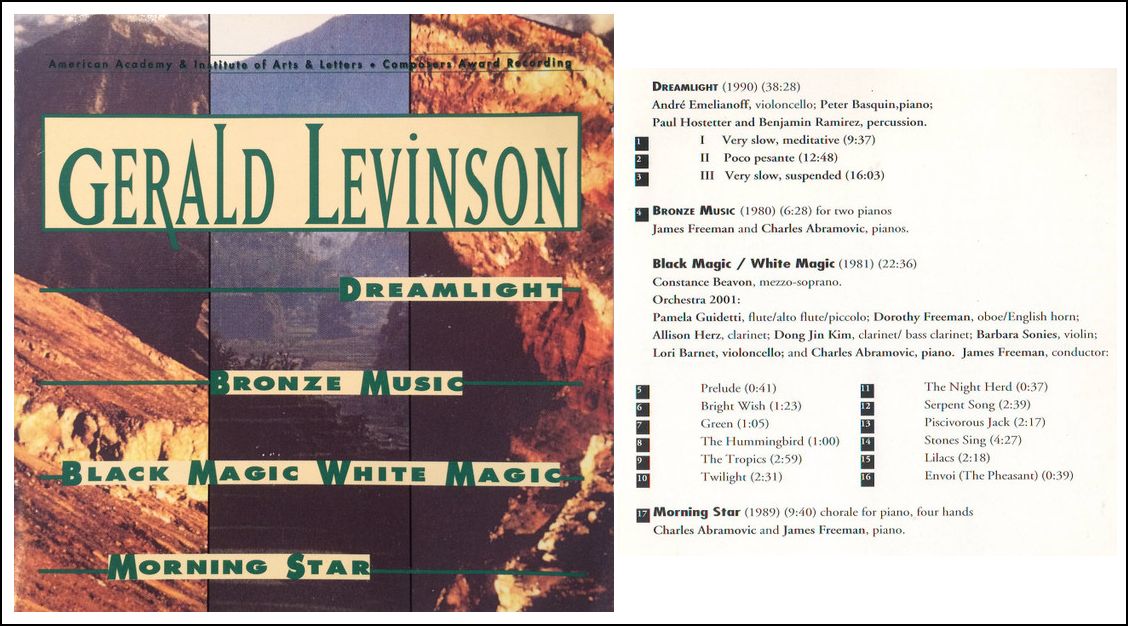

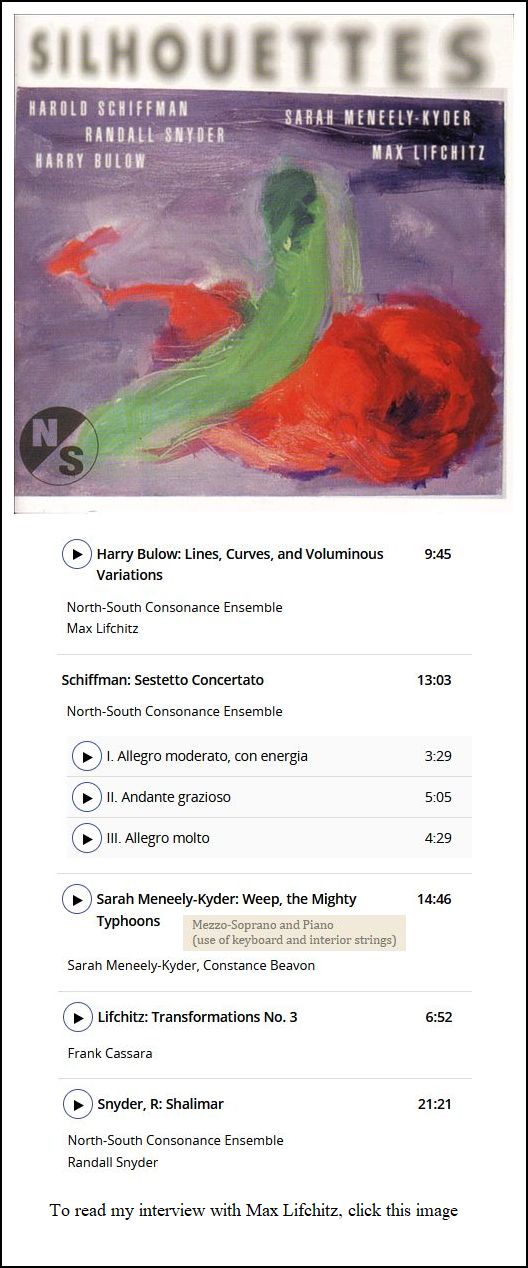

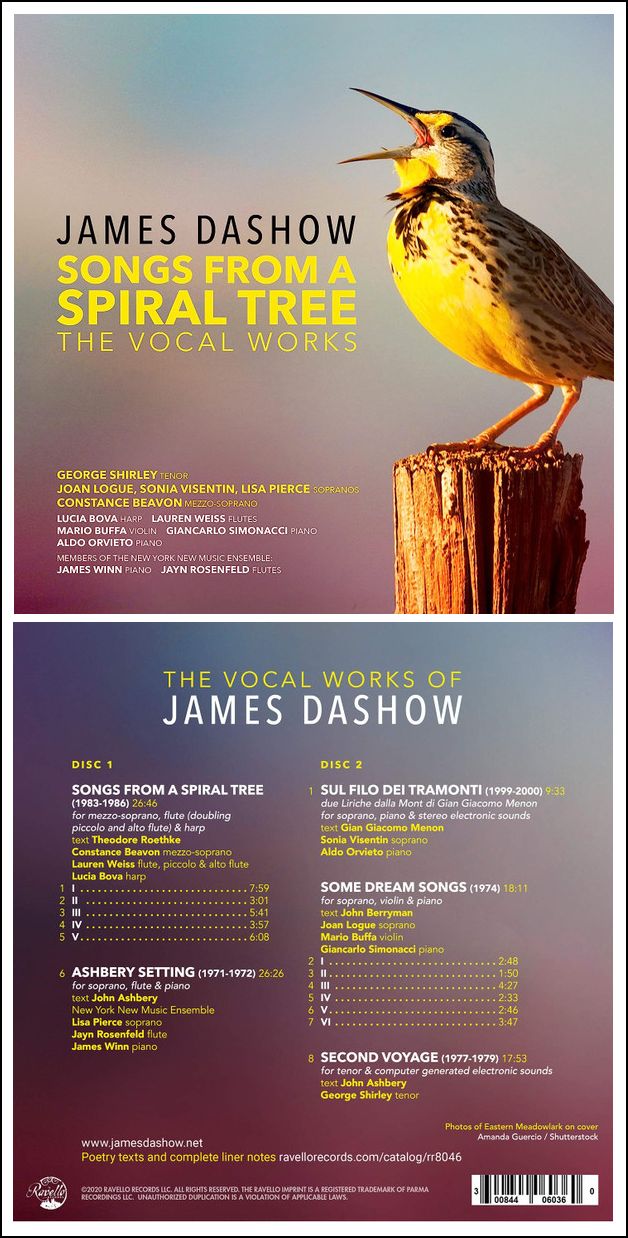

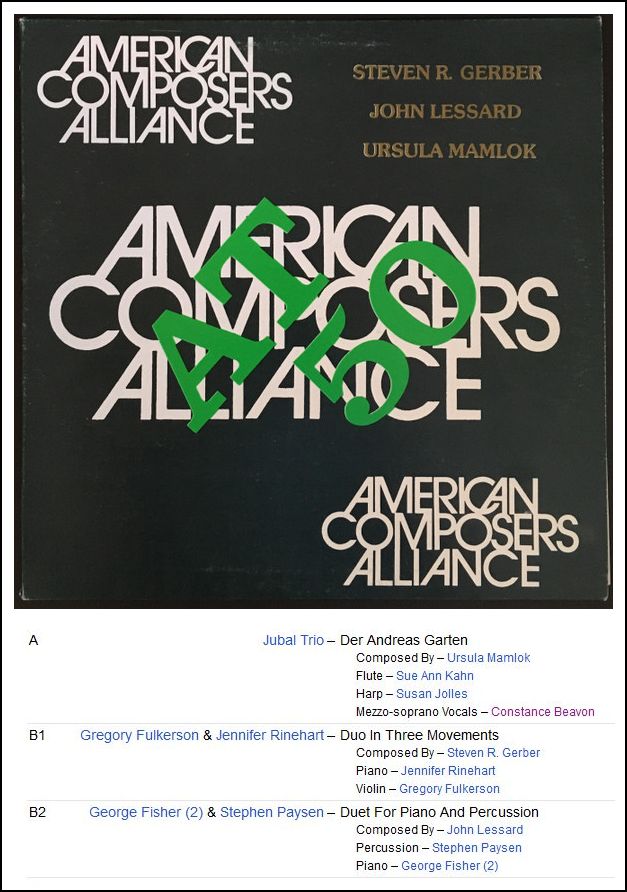

At the same time she has performed the music of our time since her earliest experiences as a musician. She has recorded and premiered more than 100 works, many written especially for her. Collaborations with composers and writers have lead to unique theatrical/musical projects such as the one woman opera It Had Wings by writer Allan Gurganus and composer Bruce Saylor, recital programs created especially for art exhibitions at the Chicago Art Institute (Odilon Redon and the Symbolist poets), the Frick Museum in Pittsburgh (Ottocento Italian Painting, Poetry and Music), the Gardiner Museum in Boston and the Jewish Museum in New York City. Additionally, Ms Beavon is a frequent performer of vocal chamber music with such distinguished organizations as Orchestra 2001, Library of Congress Summer Festival, Music Today Ensemble, Chicago Chamber Musicians, League ISCM Chamber Players, Rockport Chamber Music Festival, Jubal Trio, Campion Quartet of Rome, Meridian Strings, and Rosewood Ensemble. Her more that 50 recordings of the vocal chamber music and song repertoire of our time are available on BMG, Da Capo, Opus One, RCA, New World and Musical Heritage Recordings. Ms. Beavon is an honors graduate of Pomona College, Columbia University and New York University and holds prizes from international competitions in Montreal and Carnegie Hall. She lives in New York City with her husband, composer Bruce Saylor, and four amazing daughters. When not engaged in music, she conducts interviews and produces films about the international activism, religion, art, and poetry. |

|

In 1972–73, he was a Fulbright Fellow in composition at the Music Conservatory in Warsaw, Poland. From 1973 to 1976, Noon taught music theory and composition and supervised the advanced ear-training program at the School of Music at Northwestern University. In 1976, he was composer-in-residence at the Wurlitzer Foundation in Taos, New Mexico. From 1996 to 1998, Noon was Composer Artist-in-Residence at the Episcopal Cathedral of St. John the Divine. A prolific composer, Noon has written 232 works, including chamber music, orchestral works, and choral compositions. He has written 11 string quartets, 3 piano concertos, the opera R.S.V.P., and many works featuring percussion. He has also written 2 books of poetry: Postcards from Rethymno and Bitter Rain; 3 historical novels: The Tin Box, Googie's, and My Name Was Saul; and 3 Nadia Boulanger mysteries, Murder at the Ballets Russes, The Tsar's Daughter, and The Organ Symphony. Influenced by Stravinsky, Webern, and Boulez, Noon wrote serial music until 1975. It was in that year, in the finale of his String Quartet #1, that Noon abruptly wrote a volta in the style of a Renaissance viol consort. This was the beginning of Noon's conscious reference to styles, techniques, and formal procedures of the past. While often maintaining a fully chromatic harmonic and melodic language, Noon's music frequently makes allusions to tonal diatonicism. The sharp distinction between chromatically dissonant and diatonically tonal music has become a stylistic trait of Noon's work. He was on the faculty of Manhattan School of Music in New York

City from 1981 to 2011, where he was chairman of the Music History Department

(1981-2007), chairman of the Composition Department (1989–98), and dean

of academics (1998-2006). In 2007–08, Noon was a visiting professor of

musicology and composition at the Central Conservatory in Beijing, China.

Noon resides in New York City and on the Greek island of Crete.

== Names which are

links in this box and below refer to my interviews elsewhere on my website.

BD

|

|

He has received commissions from the Berkshire Music Center, Fromm Music Foundation, the Koussevitzky Music Foundation in the Library of Congress, National Geographic Society, Empire Brass Quintet, and others. He was the recipient of two grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, for his Concerto for Brass Quintet and Orchestra and Trumpet Concerto; and the Charles E. Ives Scholarship from the National Institute of Arts and Letters. Taxin received ASCAP and Leonard Bernstein Fellowships to Tanglewood, where he was awarded the Margaret Grant Memorial Composition Prize for the 1972 season. He received two BMI Student Composer Awards as well as the Joseph H. Bearns Prize from Columbia University for his Concerto for Piano and Chamber Orchestra. His works have been performed by major orchestras such as the New York Philharmonic, Cincinnati Symphony, and St. Paul Chamber Orchestra, and by conductors such as Pierre Boulez and Gunther Schuller. Taxin has received several Teacher Recognition Awards from the U.S. Department of Education, Presidential Scholars Program, and National Foundation for Advancement in the Arts. In addition to his concert music, he has composed, arranged, performed, directed, and produced music for television, radio, educational films, feature films, video animation, commercials, music libraries, musical theater, and stage works. Taxin is an alumnus of the BMI-Lehman Engel Musical Theatre Workshop. His music has been published by Theodore Presser Company and his brass quintets have been recorded by the Meridian Arts Ensemble. He is a member of BMI. |

© 1994 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on June 30, 1994. Portions were broadcast on WNIB three years later. This transcription was made in 2023, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.