|

Obituary from The Independent, December 19, 2008

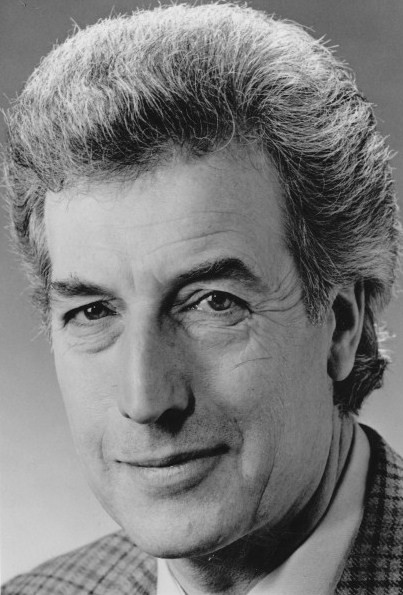

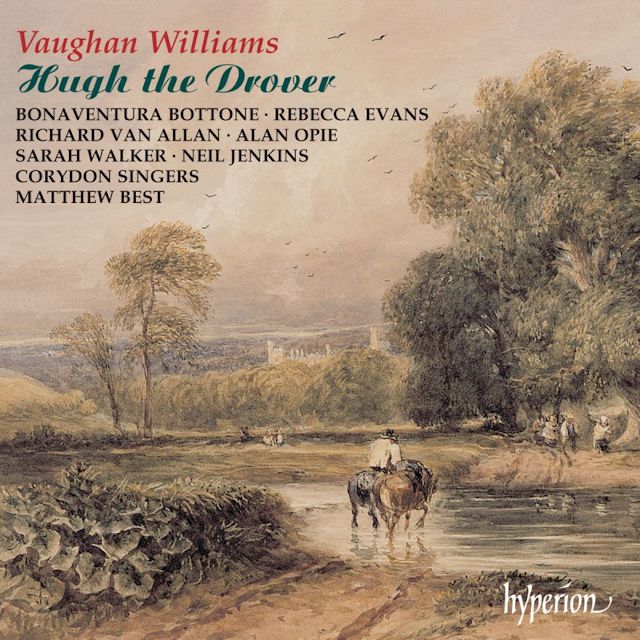

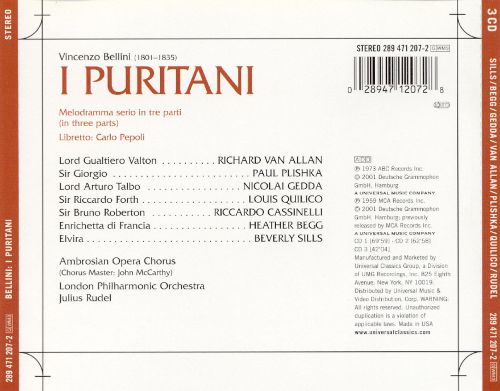

His voice was full-toned and sharply focused without being particularly large, while his diction was excellent. He was a very fine actor and often played speaking parts, including the Majordomo in Ariadne auf Naxos or the Pasha Selim in Die Enführung aus dem Serail with distinction. Towards the end of his singing career he became a popular and successful Director of the National Opera Studio. Richard Van Allan was born in Clipstone, Nottinghamshire in 1935. He served as a police officer before studying with David Franklyn at the Birmingham School of Music. He joined the Glyndebourne chorus in 1964 and two years later sang the Second Priest and the Second Man in Armour in Die Zauberflöte. In 1967 he sang Osmano in Cavalli's L'Ormindo and won the first John Christie Award. During the next five years his roles included Zaretzky in Eugene

Onegin, the Doctor in Pelléas et Mélisande,

Lord Francis Jowler in the first performance of Maw's The Rising of the

Moon (1970), Leporello in Don Giovanni, Selim in Rossini's

Il Turco in Italia and Osmin as well as the Pasha in

Die Entführung. He returned to Glyndebourne in 1977

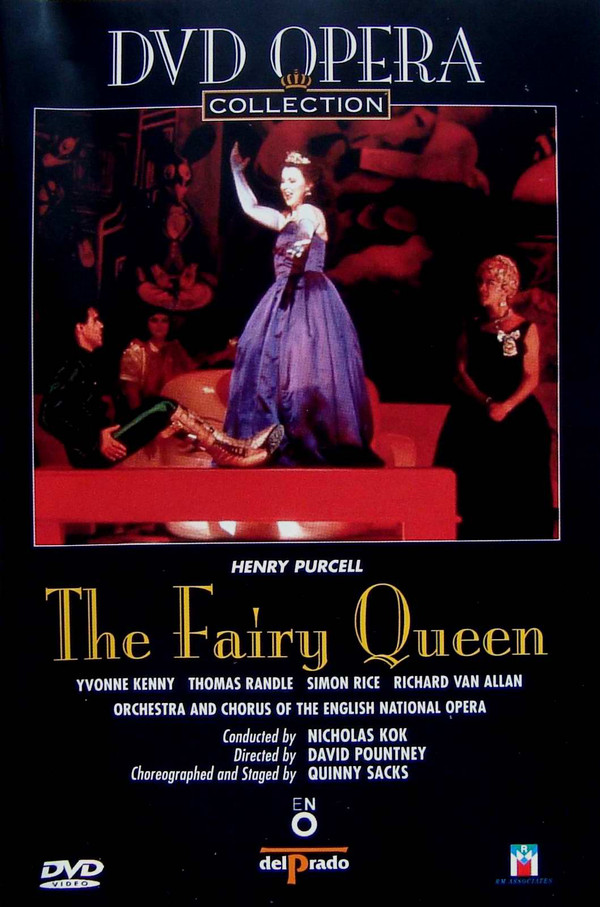

for Trulove in Stravinsky's The Rake's Progress. [Vis-à-vis the DVD shown at right, see my

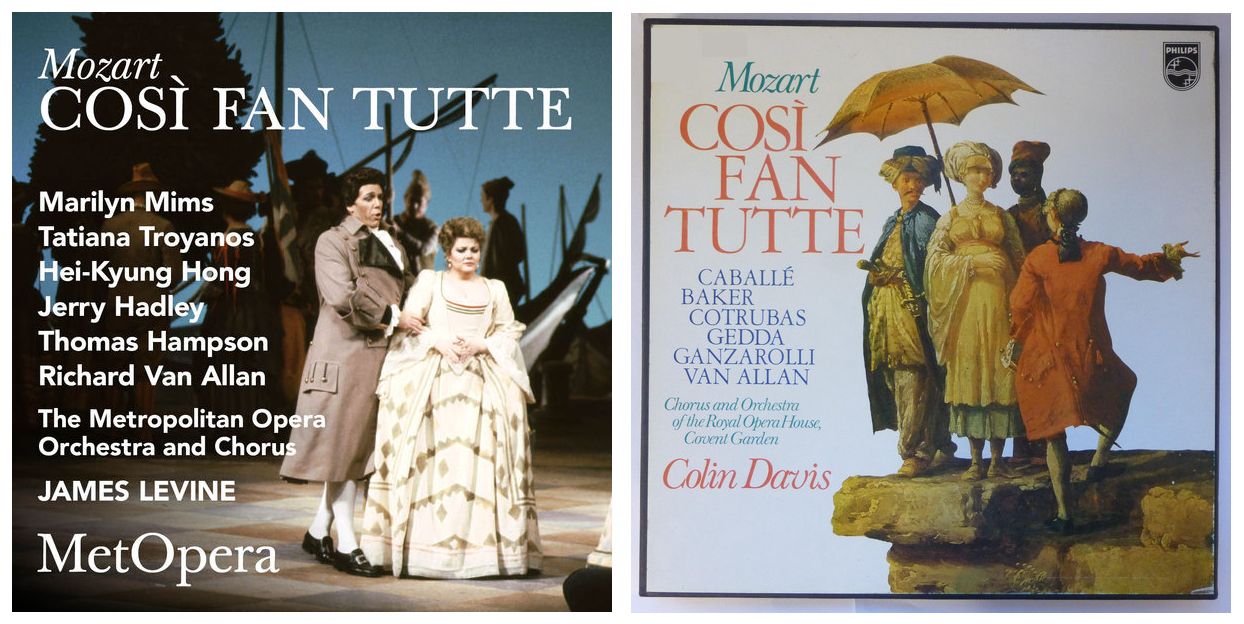

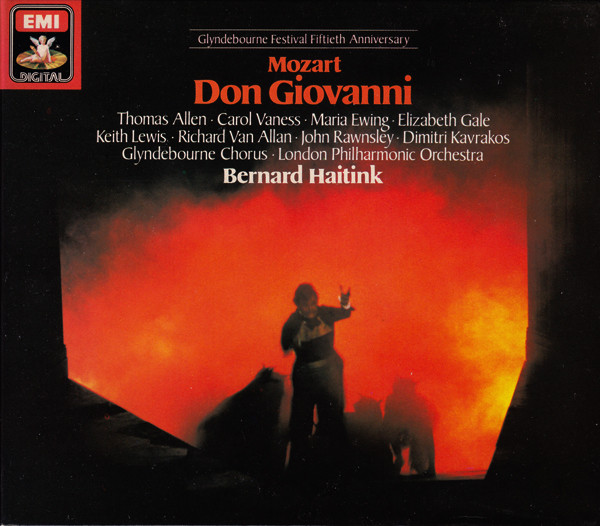

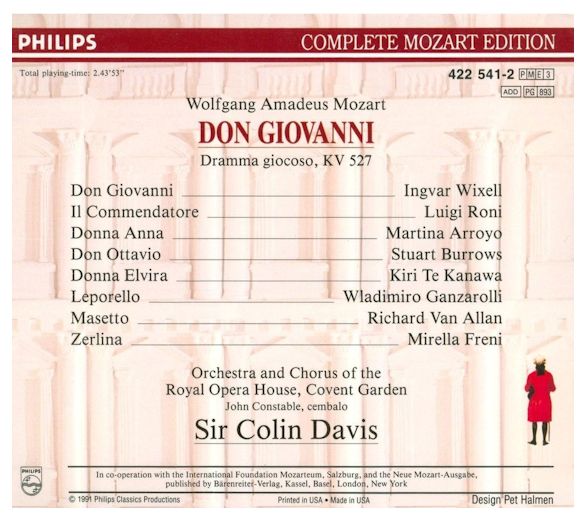

interviews He first sang for ENO (still under the name of Sadler's Wells Opera) at the Coliseum in 1969 as Don Giovanni, followed in 1970 by Don Alfonso in Così fan tutte, one of his finest roles, and as King Henry in Lohengrin in 1971. That was the year of his Covent Garden début as the Mandarin in Turandot. His other roles at Covent Garden in the 1970s included Mozart's Figaro, Don Alfonso and Leporello, the King in Aïda, the Doctor in Berg's Wozzeck, Mr Flint in Britten's Billy Budd, the Grand Inquisitor in Don Carlos, Colline in La Bohème, Ferrando in Il trovatore, Quince in Britten's A Midsummer Night's Dream and Calkas in Walton's Troilus and Cressida. Van Allan also sang Masetto, his third role in Don Giovanni, at the Paris Opéra in 1975, Don Pizarro at Boston and his first Baron Ochs in Der Rosenkavalier at San Diego in 1976. He repeated Baron Ochs at Buenos Aires and at ENO in 1978. It soon

became one of his best roles, in which the dramatic was of equal

importance to the vocal side of the performance. The same year, he

sang the Father Superior in Verdi's The Force of Destiny at

ENO; Wurm in a new production of Verdi's Luisa Miller with Luciano

Pavarotti [LP cover shown below], and Don Pedro in Meyerbeer's

L'Africaine, also a new production, with Placido Domingo,

both at Covent Garden.

See my interviews with Sherrill Milnes, Anna Reynolds, and Peter Maag

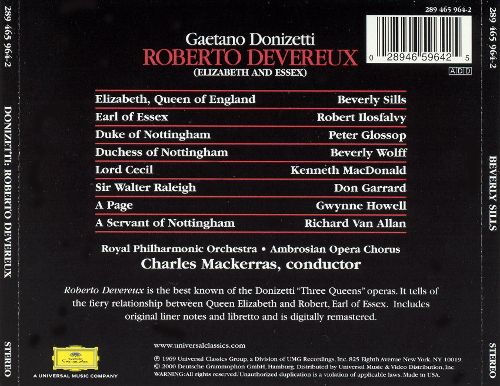

Van Allan was as busy as ever during the first half of the 1980s;

at ENO he sang Friar Laurance in Gounod's Romeo and Juliet,

the Father in Charpentier's Louise, the Water Sprite in Dvořák's

Rusalka, Collatinus in Britten's Rape of Lucretia,

Sir Walter Raleigh in Britten's Gloriana, Procida in Verdi's

Sicilian Vespers, Kochubei in Tchaikovsky's Mazeppa,

the Count in The Marriage of Figaro (for the first time),

Philip II in Don Carlos and Pooh-Bah in Jonathan Miller's

1920s production of The Mikado. In their different ways,

the last two characters were both immensely successful. At Covent

Garden he sang Capulet in Bellini's I Capuletti e I Montecchi

for Welsh National, Kecal in Smetana's Bartered Bride,

and at Glyndebourne, Superintendent Budd in Britten's Albert Herring.

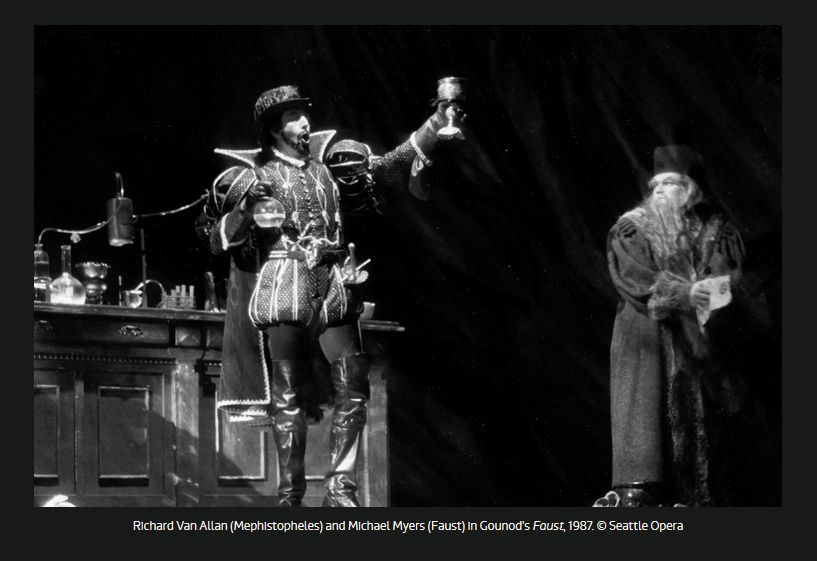

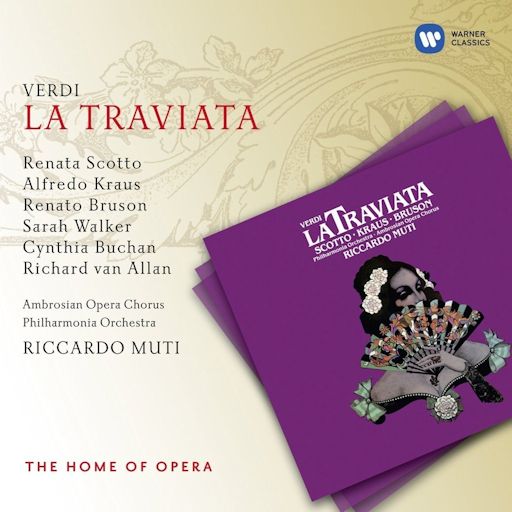

In September 1986 Van Allan was appointed Director of the National Opera Studio, set up by the Arts Council in 1978 to provide intensive training for young opera singers. He remained there for 15 years. His own appearances were of necessity rather fewer, but for a decade he continued to sing, in London and abroad. He sang Mephistopheles in Gounod's Faust at Seattle (1987); he made a magnificently evil Claggart in Billy Budd (1988) [DVD shown at right], and sang Frank Maurrant in Weill's Street Scene (1989) at ENO. He also gave his much-admired performance of Don Alfonso at the Metropolitan, New York [CD shown below]. He sang Comte de Saint-Bris in Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots (1991) at Covent Garden and Don Jerome in Gerhard's The Duenna (1992) at Barcelona. In 1994 he scored two great personal triumphs at ENO, as Prince Gremin in Eugene Onegin and in the title role of Massenet's Don Quixote. His Quixote was particularly moving. Van Allan was appointed CBE in 2002 for services to music. Elizabeth Forbes Richard Van Allan, opera singer and administrator: born Clipstone, Nottinghamshire 28 May 1935; Director, National Opera Studio 1986-2001; CBE 2002; married 1963 Elizabeth Peabody (one son; marriage dissolved 1974), 1976 Rosemary Pickering (one daughter, and one son deceased; marriage dissolved 1986); died London 4 December 2008. |

BD: What do you expect of the audience that comes to

hear your performances?

BD: What do you expect of the audience that comes to

hear your performances? BD:

Is it important for you to have confidence in the work that you do?

BD:

Is it important for you to have confidence in the work that you do? BD: So then you enjoy the luxury of going between the

Garden and the Coliseum?

BD: So then you enjoy the luxury of going between the

Garden and the Coliseum? RVA: Well, no. The Italian for me is very closely

tied to what I call ‘the three great Mozarts’

— Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così

Fan Tutte. I don’t derive as much pleasure singing them in English.

The audiences do enjoy it, but in many ways, Mozart suffers more from

translation than a lot of the operas like Verdi and Puccini. It

is a little in the same way as Strauss also suffers from translation, and

this is possibly because in both of those cases the composer was working

with a giant of a librettist. In the case of Mozart it being Da Ponte,

and Hofmannsthal in the case of Richard Strauss. Somehow the poetry

or the prose in many ways are beautiful in themselves, and are supplemented

by the music. So there you have an integration of two very great

artists, and this why I enjoy Mozart better in the original language, and

why I think Verdi and Puccini didn’t suffer badly because their librettists

weren’t in the same caliber.

RVA: Well, no. The Italian for me is very closely

tied to what I call ‘the three great Mozarts’

— Le Nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così

Fan Tutte. I don’t derive as much pleasure singing them in English.

The audiences do enjoy it, but in many ways, Mozart suffers more from

translation than a lot of the operas like Verdi and Puccini. It

is a little in the same way as Strauss also suffers from translation, and

this is possibly because in both of those cases the composer was working

with a giant of a librettist. In the case of Mozart it being Da Ponte,

and Hofmannsthal in the case of Richard Strauss. Somehow the poetry

or the prose in many ways are beautiful in themselves, and are supplemented

by the music. So there you have an integration of two very great

artists, and this why I enjoy Mozart better in the original language, and

why I think Verdi and Puccini didn’t suffer badly because their librettists

weren’t in the same caliber. BD: Does it ever confuse you at all doing one part

and thinking the other part on stage?

BD: Does it ever confuse you at all doing one part

and thinking the other part on stage?

RVA: [Thinks again] The situation obviously

has to be Goethe, but I do find the vocal writing for Mephisto very French.

Some of the recitative lines are very French in style and humor.

RVA: [Thinks again] The situation obviously

has to be Goethe, but I do find the vocal writing for Mephisto very French.

Some of the recitative lines are very French in style and humor.|

The Rising of the Moon is an operatic comedy in three acts composed by Nicholas Maw to a libretto by Beverley Cross. It premiered on 19 July 1970 at the Glyndebourne Festival conducted by Raymond Leppard and directed by Colin Graham. The title comes from the Irish patriotic song of the same name. The opera was composed over a period from 1967 to 1970 while Maw was the artist-in-residence at Trinity College, Cambridge. It was Maw's second opera, and like his first, One Man Show, is a comedy. However, while One Man Show was a farce, The Rising of the Moon is in the genre of romantic comedy with a plot about British soldiers stationed in 19th-century Ireland at the time of the Irish famines. Its premiere at Glyndebourne in 1970 during The Troubles, a period of intense ethno-political conflict in Northern Ireland, was "felt to be tactless" by some critics, according to Maw's obituary in The Daily Telegraph. Nevertheless, the opera ran at 90% capacity at Glyndebourne and was revived the following year after Maw had made adjustments to the score. The opera was subsequently performed in Bremen and Graz in 1978 and at the Guildhall School of Music in 1986. It was also revived at the Wexford Opera Festival in 1990. |

BD: Then, are you optimistic about

the future of opera?

BD: Then, are you optimistic about

the future of opera? BD: Do you think Verdi captured Shakespeare

well?

BD: Do you think Verdi captured Shakespeare

well?© 1987 Bruce Duffie

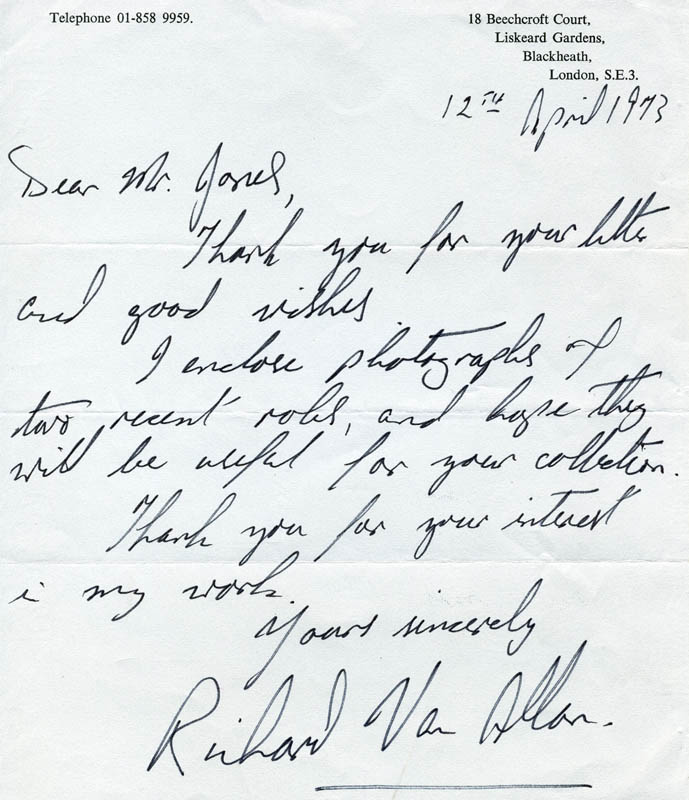

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on January 18, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990, 1995, and 1997. This transcription was made in 2018, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.