A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

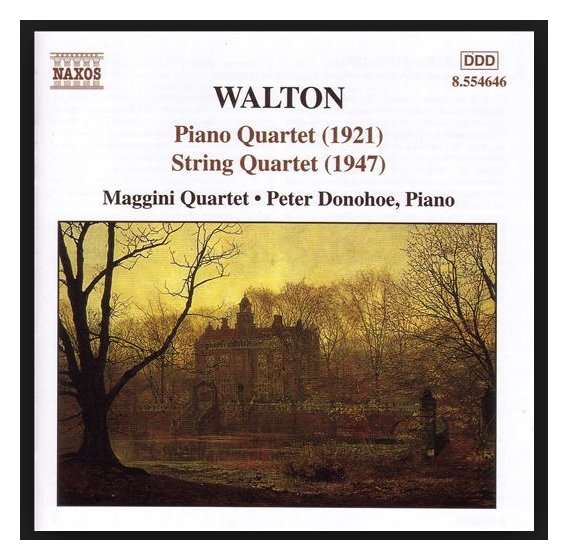

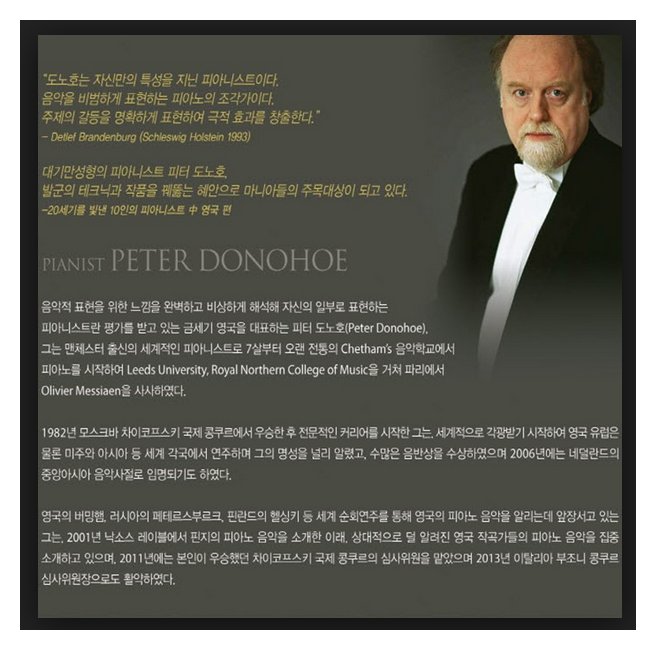

In the years since his unprecedented success as Silver Medal winner of the 7th International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1982, Peter Donohoe has built an extraordinary world-wide career, encompassing a huge repertoire and over forty years’ experience as a pianist, as well as continually exploring many other avenues in music-making. He is acclaimed as one of the foremost pianists of our time for his musicianship, stylistic versatility and commanding technique. During recent seasons Peter Donohoe’s performances included appearances with the Dresden Staatskapelle with Myung-Whun Chung, Gothenburg Symphony with Gustavo Dudamel and Gurzenich Orchestra with Ludovic Morlot. He also performed with the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and played both Brahms concertos with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra. Last season his engagements included appearances with the City of Birmingham Symphony and Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestras and an extensive tour of South America. He also took part in a major Messiaen Festival in the Spanish city of Cuenca, to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the composer’s birth. Peter Donohoe played with the Berliner Philharmoniker in Sir Simon Rattle’s opening concerts as Music Director. He has also recently performed with all the major London Orchestras, Royal Concertgebouw, Leipzig Gewandhaus, Munich Philharmonic, Swedish Radio, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Vienna Symphony and Czech Philharmonic Orchestras. He was an annual visitor to the BBC Proms for seventeen years and has appeared at many other festivals including six consecutive visits as resident artist to the Edinburgh Festival, eleven highly acclaimed appearances at the Bath International Festival, La Roque d’Anthéron in France, and at the Ruhr and Schleswig Holstein Festivals in Germany. In the United States, his appearances have included the Los Angeles Philharmonic, Boston, Chicago, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Detroit Symphony Orchestras. Since 1984 he has visited all the major Australian Orchestras many times, and since 1989 he has made several major tours of New Zealand with the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. He has also made a highly acclaimed tour of Argentina with the National Symphony Orchestra of Venezuela. He has worked with many of the world’s greatest conductors including Christoph Eschenbach, Neeme Jarvi, Lorin Maazel, Kurt Masur, Andrew Davis and Yevgeny Svetlanov. More recently he has appeared as soloist with the next generation of excellent conductors such as Gustavo Dudamel, Robin Ticciati and Daniel Harding. He is a keen chamber musician and performs frequently with the pianist Martin Roscoe. They have given performances in London and at the Edinburgh Festival and have recorded discs of Gershwin and Rachmaninov. Other musical partners have included the Maggini Quartet, with whom he has made recordings of several great British chamber works.

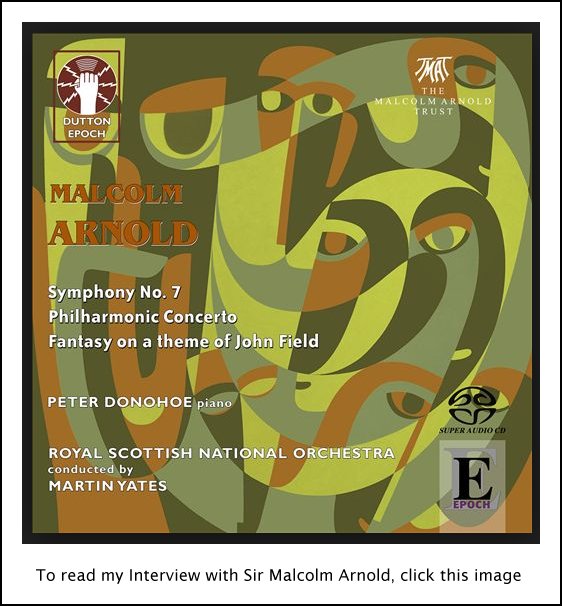

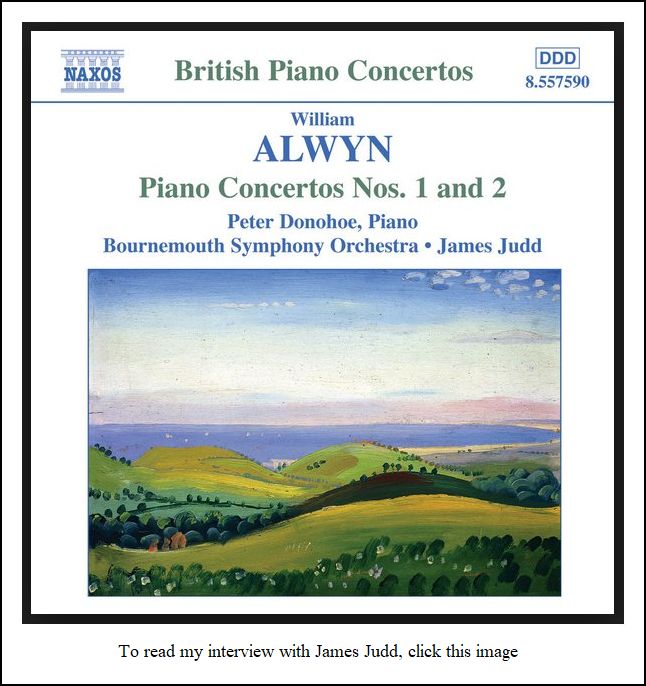

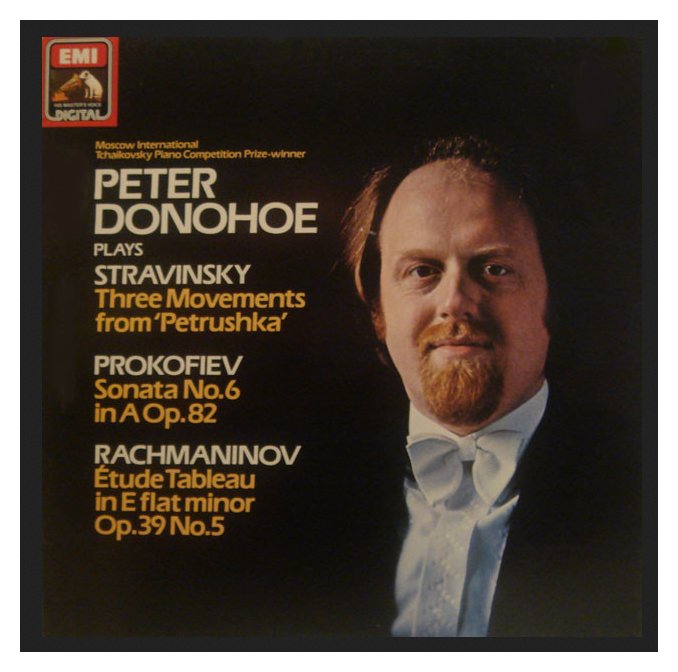

In 2001 Naxos released a disc of music by Gerald Finzi, with Peter Donohoe as soloist, the first of a major series of recordings which aims to raise the public's awareness of British piano concerto repertoire through concert performance and recordings. Discs of music by Alan Rawsthorne, Sir Arthur Bliss, Christian Darnton, Alec Rowley, Howard Ferguson, Roberta Gerhard, Kenneth Alwyn, Thomas Pitfield, John Gardner and Hamilton Harty have since been released to great critical acclaim. [Some of these are shown farther down on this webpage.]  Peter Donohoe has made many fine recordings on EMI Records, which have

won awards including the Grand Prix International du Disque Liszt for his

recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor

and the Gramophone Concerto award

for the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no.

2. His recordings of Messiaen with the Netherlands Wind Ensemble

for Chandos Records and Litolff for Hyperion have also received widespread

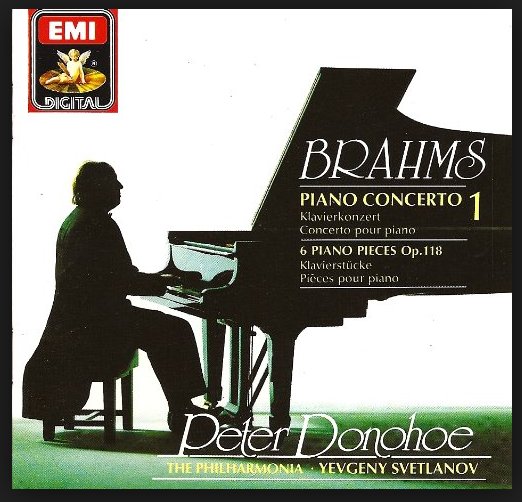

acclaim. His recording of the Brahms 1st

Concerto with Svetlanov and the Philharmonia Orchestra was voted

best available recording by the US magazine Stereo Review [shown at left].

Peter Donohoe has made many fine recordings on EMI Records, which have

won awards including the Grand Prix International du Disque Liszt for his

recording of the Liszt Sonata in B minor

and the Gramophone Concerto award

for the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto no.

2. His recordings of Messiaen with the Netherlands Wind Ensemble

for Chandos Records and Litolff for Hyperion have also received widespread

acclaim. His recording of the Brahms 1st

Concerto with Svetlanov and the Philharmonia Orchestra was voted

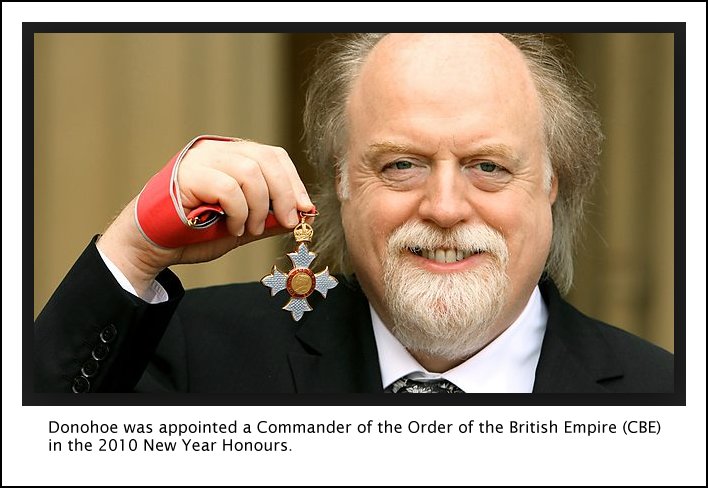

best available recording by the US magazine Stereo Review [shown at left].He studied at Chetham’s School of Music for seven years, graduated in music at Leeds University, where he studied composition with Alexander Goehr, and the Royal Northern College of Music, studying piano with Derek Wyndham. He then went on to study in Paris with Olivier Messiaen and Yvonne Loriod. His prize-winning performances at the British Liszt Competition in London in 1976, the Bartók-Liszt Piano Competition in Budapest in the same year, and the Leeds International Piano Competition in 1981 helped build a major career in the UK and Europe. Then his activity in the competitive world culminated in the International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow in 1982, which shot his name into world-wide prominence. In June 2011 he returned to Moscow as a jury member for the 14th International Tchaikovsky Competition. He is vice-president of the Birmingham Conservatoire and has been awarded Honorary Doctorates of Music from the Universities of Birmingham, Central England, Warwick, East Anglia, Leicester and The Open University.

-- Text of the biography taken

from the artist’s website.

-- Names which are links on this webpage refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD: Did they try to sell them as a sequence?

BD: Did they try to sell them as a sequence? BD:

Do you know in advance how long it will take you to become comfortable with

a piece.

BD:

Do you know in advance how long it will take you to become comfortable with

a piece. Peter: Inevitably one is, and it’s absolutely

essential that you do. But what is not essential is that you try

to. There’s a very big difference between your natural reaction to

the music, based on your own personality and your own experience, and thinking

to yourself you must make this different for the sake of it. There

is actually quite a lot of that about, and it’s a real shame. We’re

all different people anyway, and what we should do is respond to the composer

as honestly as we can. Making the music the most important thing,

and we must project that music with as much faith as we possibly can to the

people who come to listen to it. We should not say to ourselves, “I’m

going to be different; I’m going to have an ego trip on the strength of

this music and all that is implied there.” The

fact that you playing it is never more important than the music, and never

can be.

Peter: Inevitably one is, and it’s absolutely

essential that you do. But what is not essential is that you try

to. There’s a very big difference between your natural reaction to

the music, based on your own personality and your own experience, and thinking

to yourself you must make this different for the sake of it. There

is actually quite a lot of that about, and it’s a real shame. We’re

all different people anyway, and what we should do is respond to the composer

as honestly as we can. Making the music the most important thing,

and we must project that music with as much faith as we possibly can to the

people who come to listen to it. We should not say to ourselves, “I’m

going to be different; I’m going to have an ego trip on the strength of

this music and all that is implied there.” The

fact that you playing it is never more important than the music, and never

can be. BD:

Maybe he was just trying to be encouraging to those others... [Both

laugh] You get scores thrown at you all the time. Where is piano

music going these days?

BD:

Maybe he was just trying to be encouraging to those others... [Both

laugh] You get scores thrown at you all the time. Where is piano

music going these days? Peter:

In an ideal situation it definitely does become an extension of oneself,

and perhaps three or four times a decade that might happen.

Peter:

In an ideal situation it definitely does become an extension of oneself,

and perhaps three or four times a decade that might happen. BD:

That’s why you have producers?

BD:

That’s why you have producers? Peter: I’d love to face them, but you can’t

because the piano doesn’t work that way. A cellist, the violinists,

singers, and any wind soloist all have this wonderful advantage of playing

to the audience, directly looking at them. It’s very important.

It’s almost eye contact. It’s very hard to have eye contact with 3,000

people, but you can have occasional eye contact with occasional people,

and they certainly are looking directly at you, which is a very important

difference. When you’re playing the piano they see your side, and I’m

very conscious of them being ‘over there’ on my right, which they usually

are, although if you play two-piano music then they can be on your left!

But they are never in front of you.

Peter: I’d love to face them, but you can’t

because the piano doesn’t work that way. A cellist, the violinists,

singers, and any wind soloist all have this wonderful advantage of playing

to the audience, directly looking at them. It’s very important.

It’s almost eye contact. It’s very hard to have eye contact with 3,000

people, but you can have occasional eye contact with occasional people,

and they certainly are looking directly at you, which is a very important

difference. When you’re playing the piano they see your side, and I’m

very conscious of them being ‘over there’ on my right, which they usually

are, although if you play two-piano music then they can be on your left!

But they are never in front of you.

© 1998 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on October 28, 1998. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 2001, on WNUR in 2010 and 2011, and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2010. This transcription was made in 2016, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.