Nicholas Maw

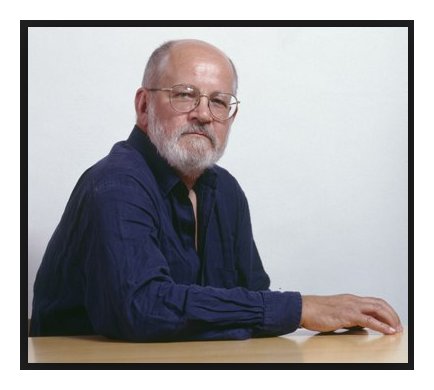

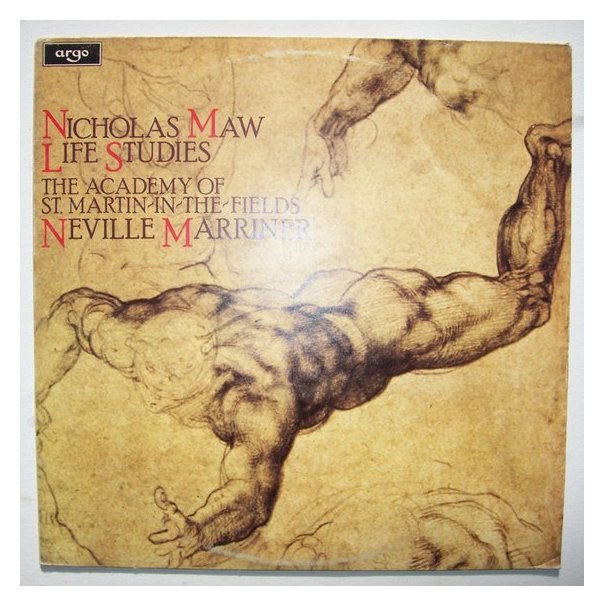

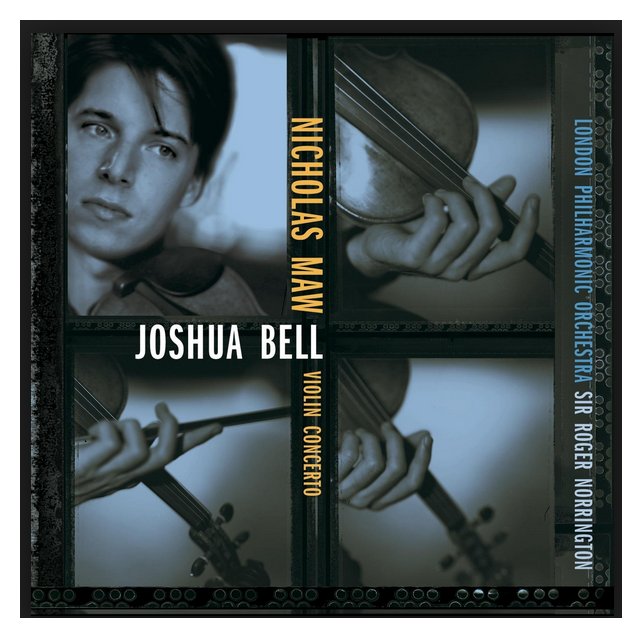

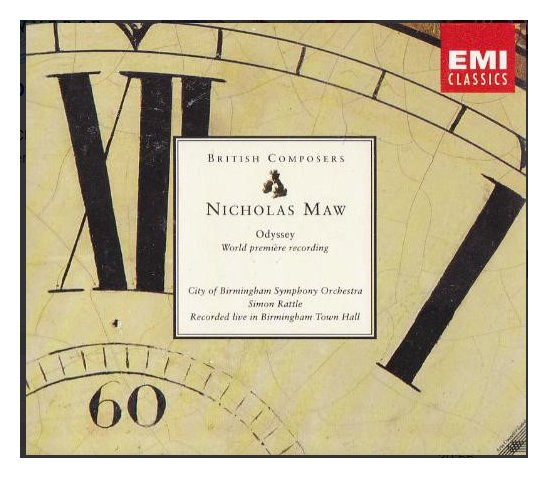

(November 5, 1935 - May 19, 2009) Nicholas Maw is one of Britain’s most admired composers. He was an acknowledged master in whatever genre he expressed himself, and one whose musical language is instantly recognisable. Born in 1935 in Grantham, Lincolnshire, he studied at the Royal Academy of Music, London (1955-58) with Paul Steinitz and Lennox Berkeley; and in Paris with Nadia Boulanger and Schoenberg’s pupil, Max Deutsch. His career as a teacher has included positions at Trinity College Cambridge, Exeter University, Yale University, and latterly he was Professor of Composition at the Peabody Conservatory, Baltimore. Prizes and awards he has won include the 1959 Lili Boulanger Prize, the 1980 Midsummer Prize of the City of London, the 1991 Sudler International Wind Band Composition Competition for American Games, and the 1993 Stoeger Prize from the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center. Maw received commissions from many of the major musical organisations in the United Kingdom such as the BBC, the Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Philharmonia Orchestra, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, the Royal Opera House, the Nash Ensemble, the English Chamber Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the London Sinfonietta, to name but a few, and he has been the featured composer at the South Bank Summer Music Festival (1973), the Kings Lynn Festival (1985), the BBC ‘Nicholas Maw Day’ at the South Bank (1989), the Bath Festival (1991), the Park Lane Group and the Royal Academy of Music’s British Music Festival (1992), the 60th Birthday Malvern Weekend (1995) and the Chester Festival (1999). His extensive and varied catalogue includes much chamber, vocal and choral music, two comic operas (the chamber opera One Man Show, 1964, and the three-act The Rising of the Moon, 1967-70), solo instrumental works, and music for children. Maw is, however, most celebrated for his orchestral music: his reputation being established when, at the age of 26, he produced Scenes and Arias (1962) for a BBC Prom, which immediately put him right at the forefront of the British musical scene. This BBC commission is now recognised as one of the most outstanding British works of its decade. In addition to fulfilling other numerous commissions, from 1973 to 1987 Maw composed Odyssey for orchestra: the single, unbroken 96-minute span of symphonic music which has been unanimously lauded since its initial performance in 1987 at a BBC Prom in London. The EMI recording by Simon Rattle and the CBSO was nominated for a Grammy Award in 1992 and cited by Classic CD (June 2000) as the best recording out of a hundred recommended releases in the decade. Leonard Slatkin and the St Louis Orchestra gave the American premiere of Odyssey in St Louis and New York’s Carnegie Hall in 1994. Other important orchestral works by Nicholas Maw are his lively and joyous Spring Music (1983), the orchestral nocturne The World in the Evening (1988) and his lyrical Violin Concerto (1993) premiered by Joshua Bell, Roger Norrington and the Orchestra of St. Luke’s in New York, and the Philharmonia Orchestra in London, under Slatkin in 1993, which was recorded for Sony and nominated for the 2000 Mercury Prize. Other recordings include: American Games (Klavier); Dance Scenes (EMI Classics); Ghost Dances, Roman Canticle, La Vita Nuova (ASV); Odyssey (EMI Classics); Piano Trio, Flute Quartet (ASV); Sonata Notturna/Life Studies (Nimbus); Hymnus/Little Concert/Shahnama (ASV); Sophie’s Choice DVD (OpusArte). Since 1984, Maw divided his time between Europe and the United States. There has been a resultant upsurge of performances in the US from many major American ensembles, soloists and orchestras: such as the orchestras of Philadelphia, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Indianapolis, Minneapolis, San Francisco and National Symphony (Washington DC), and the Lincoln Center Chamber Players. At the same time he was very much a part of musical life in the UK. He had commissions in 1995 from the BBC (for which he produced Voices of Memory) and from the Philharmonia Orchestra for their 50th Birthday Gala (Dance Scenes), and in 1996 the BBC announced it was co-founding a Royal Opera commission to the composer to write an opera based on William Styron’s novel Sophie’s Choice. This work was premiered in the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, in December 2002 under the baton of Sir Simon Rattle in a production by Trevor Nunn. It was also staged in Berlin and Vienna a few years later – a production also seen in Washington DC. Perhaps the warmth of the reception in America can be most aptly summed up by Richard Dyer’s comment in the Boston Globe that ‘for generations people will be buying tickets to hear his music’, which echoes earlier words from the British critic Malcolm Hayes on Odyssey: ‘There are very few post-war works whose substance, technical control, sheer range of thought, wonderful playability and - above all - whose magnificent attitude look set to ensure that they’re still going to be played in 50 years’ time (and beyond). I think Odyssey will be one of them’. -- From the website of Faber Music

(slightly edited)

-- Names on this webpage which are links refer to my Interviews elsewhere on my website. BD |

BD:

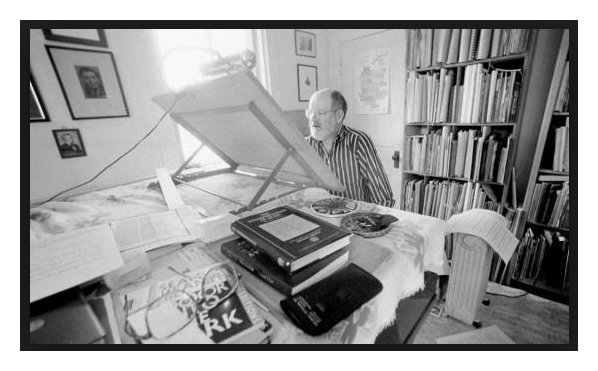

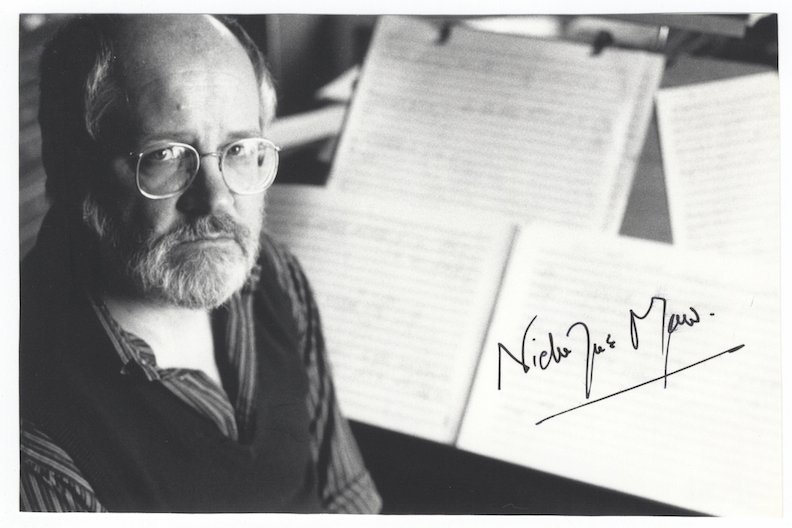

Good! Let’s begin our discussion just a little bit about that manuscript.

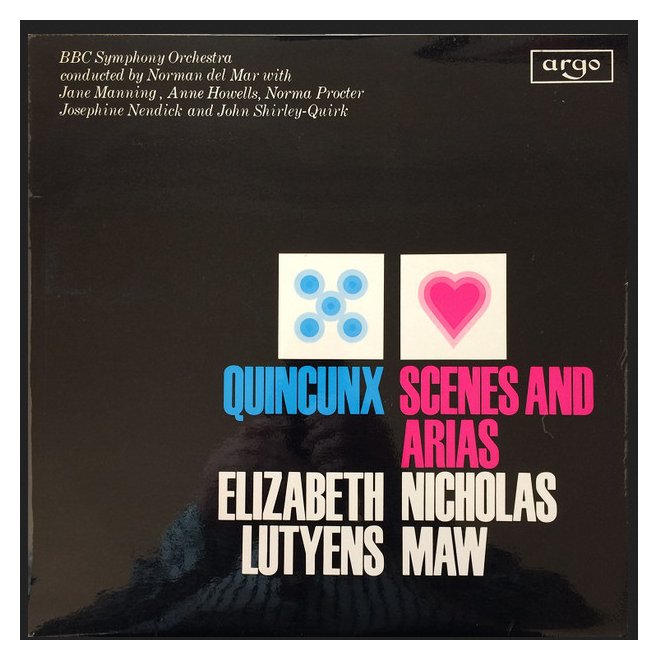

Is that the definitive score of Scenes and

Arias? [Vis-à-vis the

recording shown at right, see my Interviews with Anne Howells, and John Shirley-Quirk.]

BD:

Good! Let’s begin our discussion just a little bit about that manuscript.

Is that the definitive score of Scenes and

Arias? [Vis-à-vis the

recording shown at right, see my Interviews with Anne Howells, and John Shirley-Quirk.] NM: That’s another good question. I’m always

asking students how they know when a piece is finished, and it is a good question.

The only answer I can give you is that there’s some instinctive thing about

realizing your imagined and envisaged form. There’s some instinctive

thing about you deciding you’ve realized this to whatever extent you have

realized it. Although, when you have to deliver up the manuscript,

sometimes you feel that you have not achieved this — that

you have not managed to realize the form that you envisaged —

and it usually makes one very unhappy. It makes me unhappy.

Of course there are some things when it is very simple to know when the piece

is finished. If you’re writing a song or anything with a text, that

answers itself. But if you’re writing just pure music, the question

is much more difficult, and the best answer I can give you is an almost instinctive

feeling that you’ve realized the form, and that you have fully, as it were,

accounted for the material that you’ve invented in the piece.

NM: That’s another good question. I’m always

asking students how they know when a piece is finished, and it is a good question.

The only answer I can give you is that there’s some instinctive thing about

realizing your imagined and envisaged form. There’s some instinctive

thing about you deciding you’ve realized this to whatever extent you have

realized it. Although, when you have to deliver up the manuscript,

sometimes you feel that you have not achieved this — that

you have not managed to realize the form that you envisaged —

and it usually makes one very unhappy. It makes me unhappy.

Of course there are some things when it is very simple to know when the piece

is finished. If you’re writing a song or anything with a text, that

answers itself. But if you’re writing just pure music, the question

is much more difficult, and the best answer I can give you is an almost instinctive

feeling that you’ve realized the form, and that you have fully, as it were,

accounted for the material that you’ve invented in the piece. BD:

Are you ever surprised by what you hear?

BD:

Are you ever surprised by what you hear? NM:

Yes, I think so. Another thing is that in some cases I’ve been around

long enough now, and some of my works are on their third generation of players.

As a new generation comes along, they seem to solve problems which had been

very serious problems for their elders. They just play the piece, and

this has something to do with a gradual rise in certain performance standards,

I guess.

NM:

Yes, I think so. Another thing is that in some cases I’ve been around

long enough now, and some of my works are on their third generation of players.

As a new generation comes along, they seem to solve problems which had been

very serious problems for their elders. They just play the piece, and

this has something to do with a gradual rise in certain performance standards,

I guess. NM: [Laughs] Of course for different

composers you give different advice! The only advice that I would give

to composers is to try and put down what you hear. That sounds blatantly

obviously, I know, but we’ve just passed through a period of musical history

where that has not been considered the most important question.

I happen to believe that it is the most important question. It’s the

only thing which is really worth pursuing, so that’s the only piece of advice

that I would give them — just try to put down what

you hear, and try to hear what you put down. They are like heavenly

twins.

NM: [Laughs] Of course for different

composers you give different advice! The only advice that I would give

to composers is to try and put down what you hear. That sounds blatantly

obviously, I know, but we’ve just passed through a period of musical history

where that has not been considered the most important question.

I happen to believe that it is the most important question. It’s the

only thing which is really worth pursuing, so that’s the only piece of advice

that I would give them — just try to put down what

you hear, and try to hear what you put down. They are like heavenly

twins. NM: Good. The great power of music is that

is goes straight into the bloodstream. You can’t escape it in a sense.

It has a tremendous power entering into your consciousness and taking over,

and in my view, much of it is more so than a visual experience. I don’t

say there aren’t other things which are as powerful as this, but music is

very powerful in that respect, and it appears to be necessary for us as human

beings. It actually goes back to that latent function that I was talking

about of singing and dancing. That’s about as near to a purpose as I

can get at the moment. [Laughs]

NM: Good. The great power of music is that

is goes straight into the bloodstream. You can’t escape it in a sense.

It has a tremendous power entering into your consciousness and taking over,

and in my view, much of it is more so than a visual experience. I don’t

say there aren’t other things which are as powerful as this, but music is

very powerful in that respect, and it appears to be necessary for us as human

beings. It actually goes back to that latent function that I was talking

about of singing and dancing. That’s about as near to a purpose as I

can get at the moment. [Laughs] NM: Do you think so? Do you think, for example,

that what is paramount in their minds is the confusion?

NM: Do you think so? Do you think, for example,

that what is paramount in their minds is the confusion?| One of the most often-quoted descriptions

of opera is that of Dr Samuel Johnson, who famously defined opera in the mid-eighteenth

century as ‘an exotic and irrational entertainment’. Johnson’s response to

opera was at one with a prevailing English attitude of curmudgeonly roast-beef-and-ale

xenophobia presented as bluff common sense, and was aimed primarily at Italian

opera. His suspicion of Italian opera was shared by writers such as Joseph

Addison and Richard Steele in The Spectator,

the poet Alexander Pope (who represents opera as a foreign ‘harlot form’

in The Dunciad), and the painter

William Hogarth, who satirized the Whig aristocracy’s cultivation of Italian

opera (and other such foreign affectations) in prints and paintings. The

literal meaning of exotic is, indeed, ‘foreign’ (as Johnson’s own dictionary

explains), and this may be all that Johnson implied when he used the term,

in this instance quite accurately; for, despite indigenous attempts at the

form in the seventeenth century, by the eighteenth century opera was perceived

as an essentially foreign import to Britain, being largely performed there

in a foreign language with foreign performers. And for most countries in

the world for the first two centuries of its existence opera would be exotic

beyond Italy since, France aside, it was generally assumed that opera was

Italian per se. The majority of opera composers were Italians, many working

in countries outside of Italy; but many non-Italian composers such as Handel,

Gluck, Haydn or Mozart predominantly set operas in Italian, usually outside

of Italy too. |

© 1995 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on July 13, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB four months later, and again in 2000. This transcription was made in 2017, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.