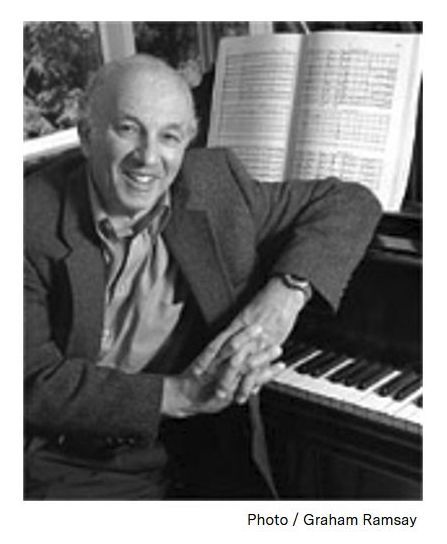

Retired MIT Conductor David Epstein dies at 71;

Brought the joy of music to campus for 33 years

MIT News on campus and around the world January

17, 2002

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. -- Professor David M. Epstein conducted Beethoven's

Ninth Symphony at his farewell performance with the MIT Symphony

Orchestra.

Ode to Joy was a fitting finale to Dr. Epstein's career at the Institute. The concert, at Kresge Auditorium on March 14, 1998, capped a 33-year career during which he brought the joy of music to the MIT campus.

Dr. Epstein, 71, died on Tuesday, Jan. 15, at Emerson Hospital in Concord, Mass., from complications of lung and liver disease. A memorial service will be held in the Wong Auditorium in MIT's Tang Center at 2 p.m. on Sunday, April 21.

Bonnie Kellerman, recording secretary in the MIT Treasurer's office, played many concerts with the second violin section under the direction of Dr. Epstein as an undergraduate and as a staff member, including at his final performance.

"It was a thrill for each of us in the orchestra to once again have the opportunity of having David lead us in making beautiful music," said Kellerman, class of 1972. "David was an educator who gave a great deal to all who had the privilege of knowing him."

Kellerman organized an orchestra reunion weekend of events surrounding the concert, celebrating the conductor's career. Her memory of a post-rehearsal luncheon that lasted six hours is still vivid. "David was so enjoying catching up with his former students, sharing his visions and passion for his upcoming undertakings, and generally imparting knowledge about music and other related topics," she said.

MIT Professor Alan J. Grodzinsky joined the orchestra as a freshman in 1965, Dr. Epstein's first year on the podium. Grodzinsky was the principal viola player for eight years and toured with MITSO. "David made it clear to students that MITSO was an organization that made real music-an intense, serious, but also extraordinarily enjoyable experience at the end of the day," said Grodzinsky, who also performed at the final concert.

Grodzinsky, director of the MIT Center for Biomedical Engineering, took Dr. Epstein's course in Music from the Baroque and Romantic Era. "He was a really enthusiastic and clear lecturer," he recalled. "I remember his playing at the piano, and his comments at the end of our first term paper that MIT students were incredibly smart, fun to teach, but terrible writers."

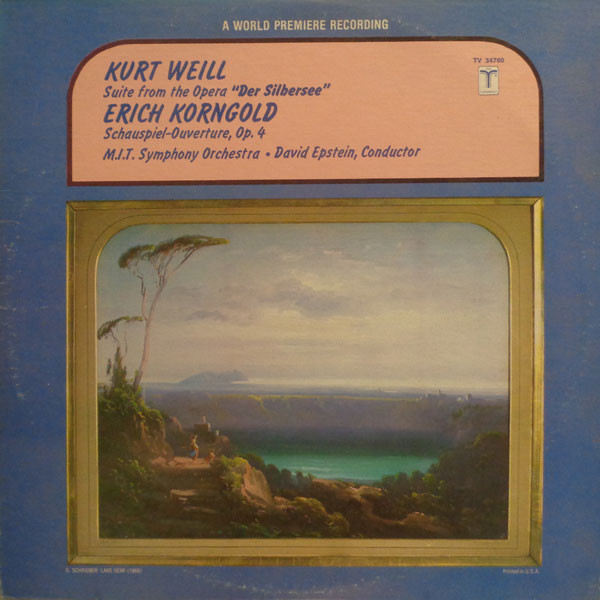

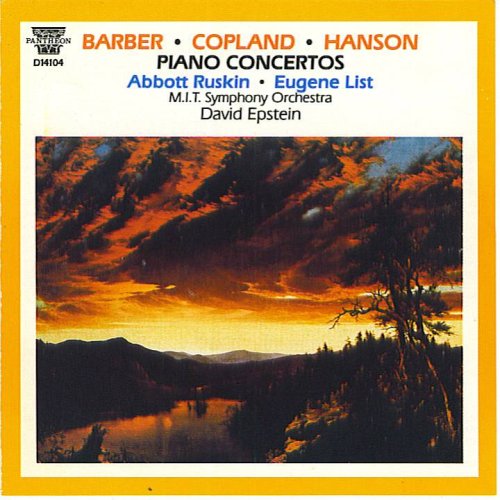

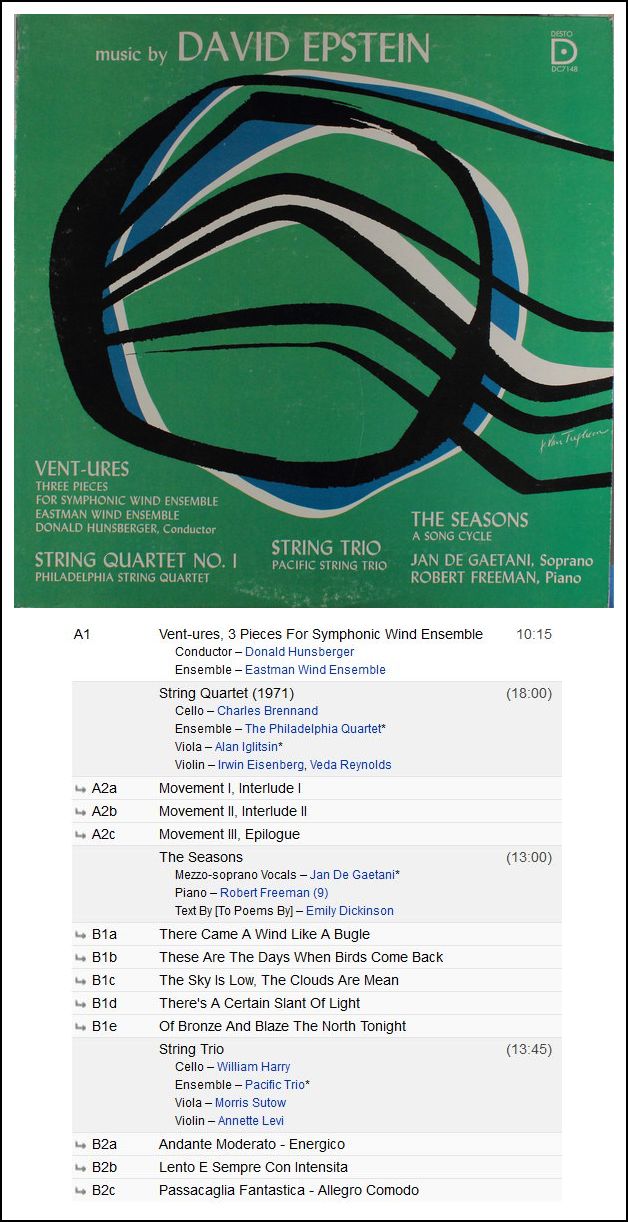

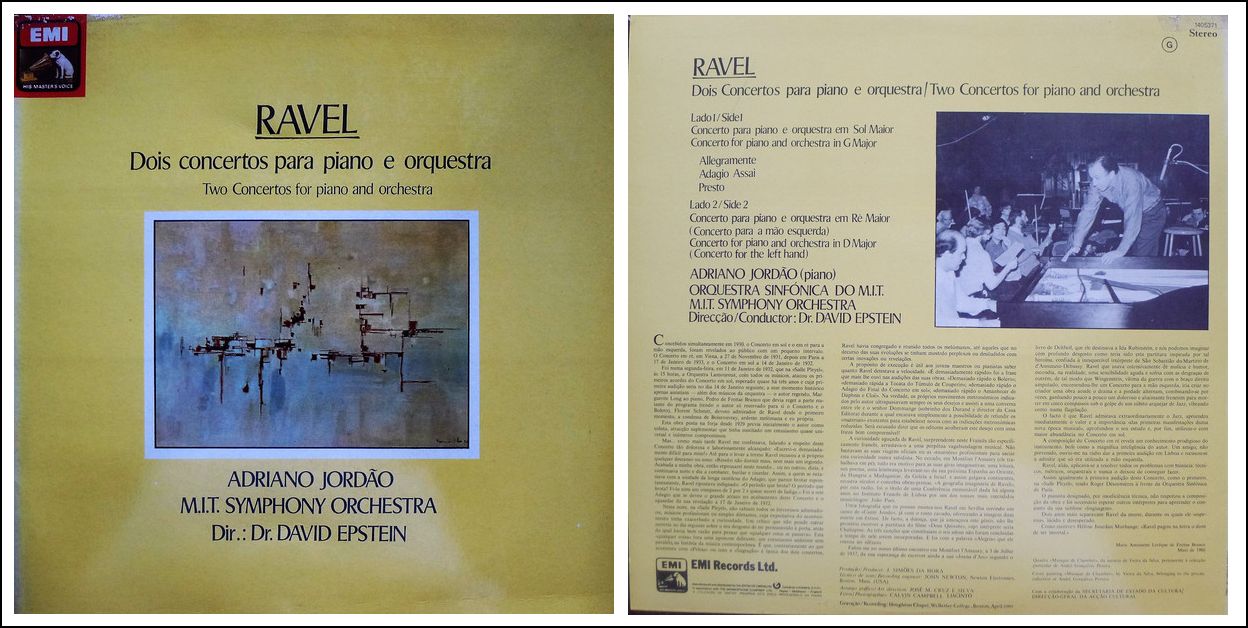

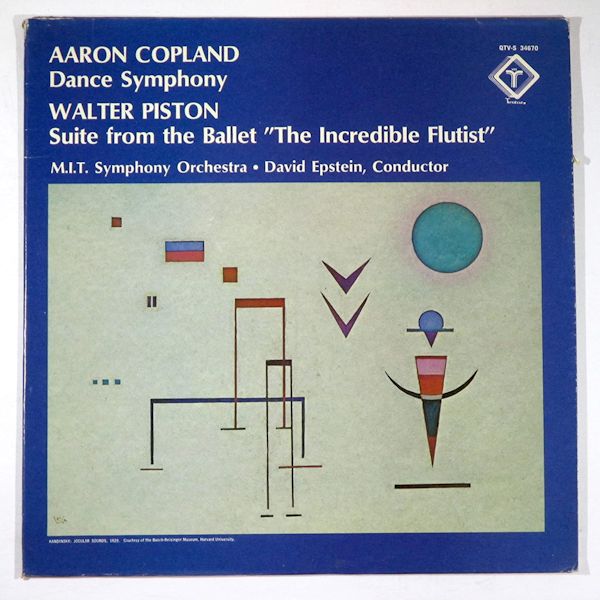

Dr. Epstein expanded MITSO's audience by mixing new and rarely heard works with those of major composers in the same program, engaging professional and student soloists, and planning and leading tours throughout the United States and abroad. He wrote insightful listener notes and embarked on an ambitious commercial recording venture with the orchestra, which has preserved on the VOX label more than a decade of its finest performances. Due primarily to his drive to raise its artistic goals and standards, the orchestra became the first co-curricular performing ensemble through which MIT students could earn study credit toward a degree.

"David Epstein's contribution to the vitality of music making at MIT is broad and deep," said Professor Marcus A. Thompson, a violist who collaborated frequently with Dr., Epstein. He noted that Dr. Epstein's "scholarly inquiry" into structure, tempo and articulation provided guidance for performers to make better interpretive decisions. "Some of this inquiry grew out of the obvious pleasure he took in teaching as well as learning from students and colleagues in the MIT scientific community," Thompson said.

A 1952 graduate of Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Dr. Epstein had graduate degrees from the New England Conservatory, Brandeis University and Princeton University. He received a Ph.D from Princeton in 1968.

Prior to joining the MIT faculty as an associate professor and conductor of MITSO in 1965, Dr. Epstein taught at Antioch and Sarah Lawrence College. He became a full professor in 1971 and chaired the Department of Music in 1982-83 and 1988-89.

Dr. Epstein helped to found the New York Youth Symphony Orchestra and conducted its debut concert in 1963 at Carnegie Hall, featuring a 17-year-old violin prodigy named Itzhak Perlman. Later in his career, he was on the podium with the New Orchestra of Boston when it performed with legendary jazz drummer Max Roach.

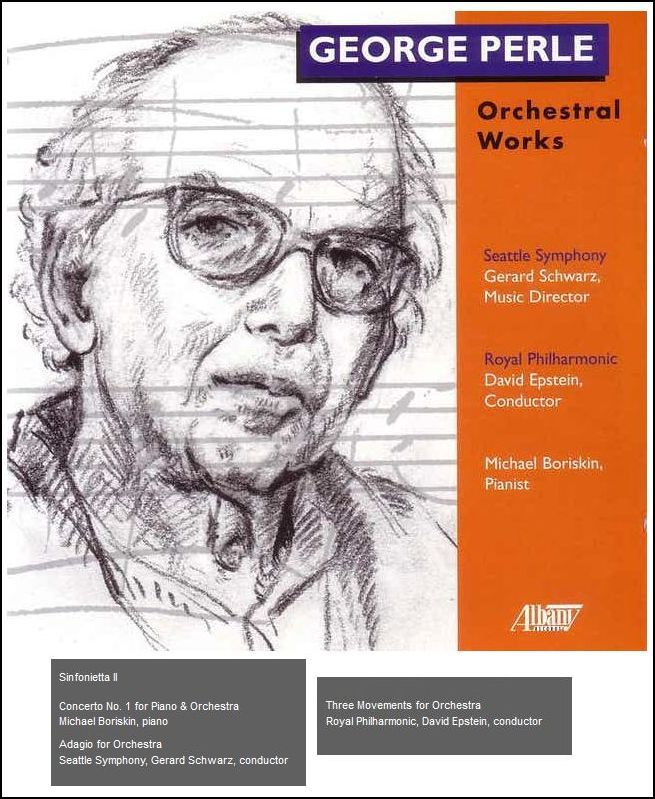

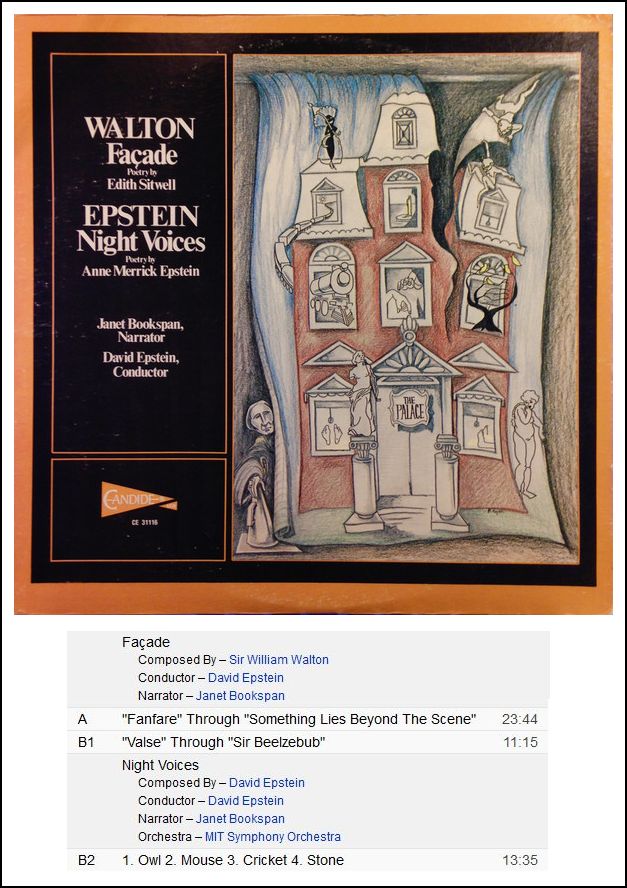

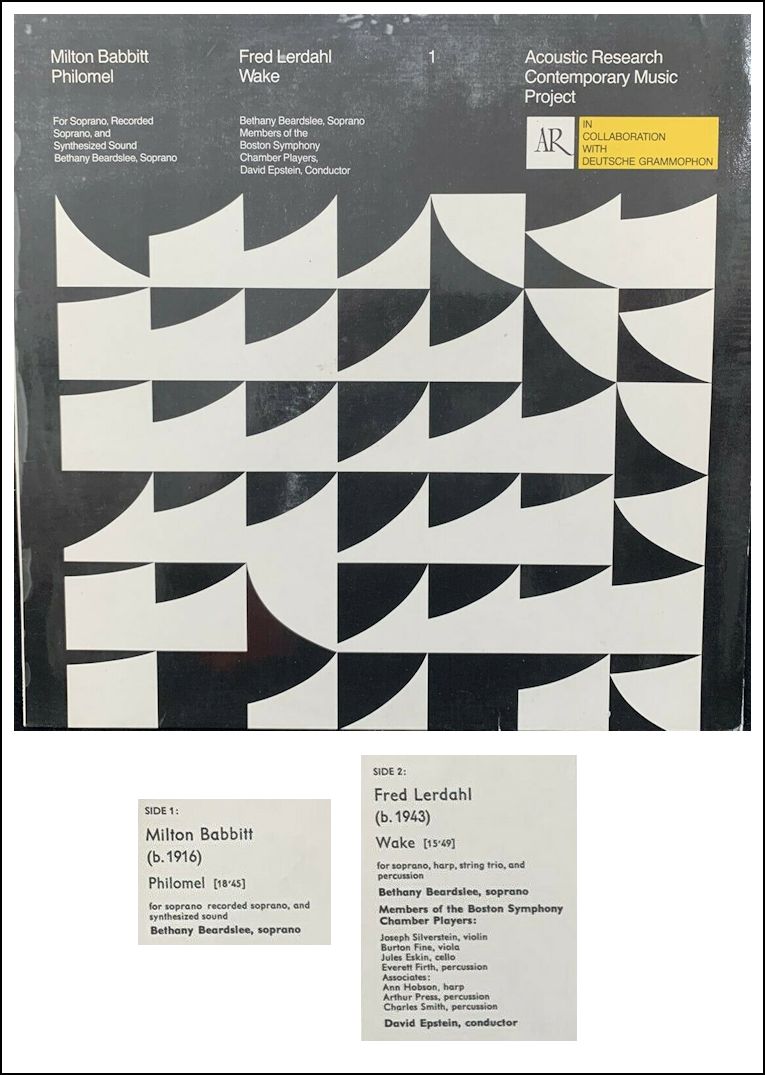

He was music director of the Harrisburg (Pa.) Symphony Orchestra from 1974 to 1978 and the Worcester Orchestra from 1976 to 1980. He appeared as a guest conductor with 28 orchestras in nine countries, including the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, the Jerusalem Orchestra and the Berlin Radio Orchestra. He conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1972 in the premier of Night Voices, written on commission for the BSO by Dr. Epstein and his wife, Anne, an author of children's books.

While at MIT, Dr. Epstein observed that brilliance in science and music often went hand in hand. "As with many of us, my students were my professors," he wrote in an essay on music and science in 2000, when he was an MIT senior fellow in the arts and humanities. "In a way, we enjoy at MIT what some 100 years ago was a norm in European culture, a diverse, literate and active musical society."

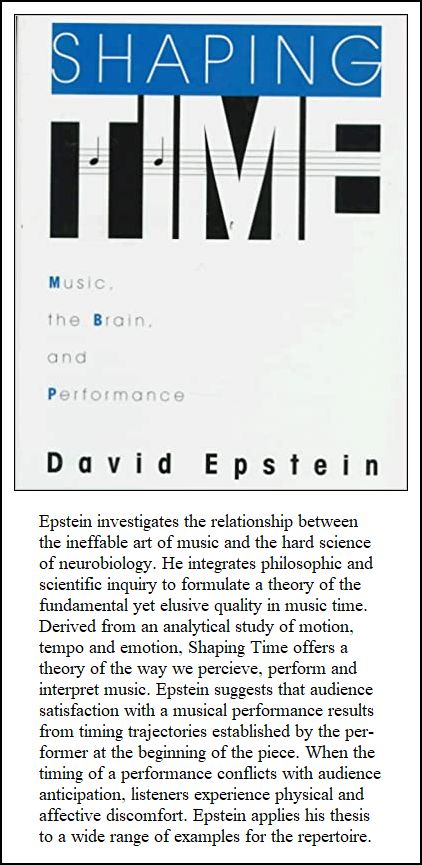

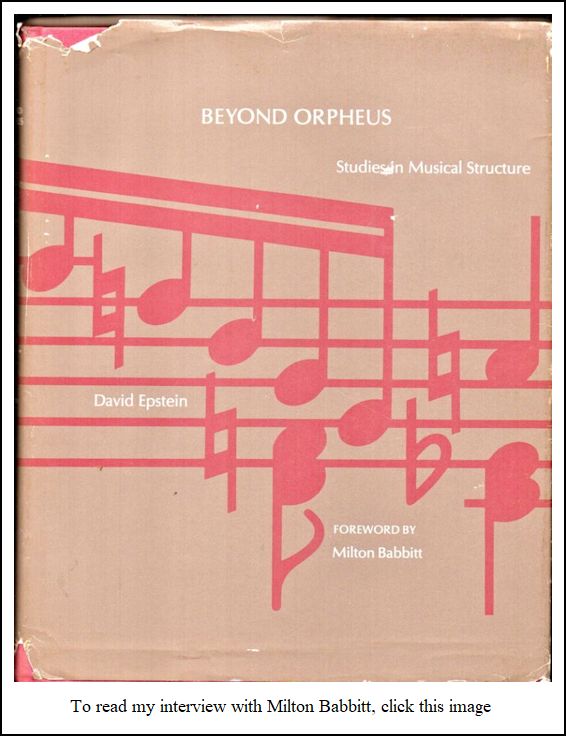

Dr. Epstein, a fellow of the Alexander Humboldt Foundation, did research on music and the brain at the Max Planck Institute for Behavioral Physiology in Germany which led to theories about the role time and motion play in music of all cultures. He explored these theories in two books, "Beyond Orpheus: Studies in Musical Structure" (MIT Press, 1979) and "Shaping Time: Music, the Brain and Performance" (Schirmer Books, 1995), which won the Deems Taylor Award from the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1996. This work led to a visiting fellowship at the Neurosciences Institute in La Jolla, Calif., founded and directed by Gerald M. Edelman, 1972 Nobel laureate for medicine.

While at Antioch in the 1950s, Dr. Epstein helped desegregate barbershops in Ohio when he testified against a white barber who claimed he was not able to cut African American hair. Dr. Epstein, who had thick, black curly hair at the time, had it cut by the barber and then appeared as a witness against him in the successful suit.

A native of New York City, he loved to ski and sail and maintained a shop in the garage of his Lexington home in which he exercised his mechanical creativity. Among his inventions were a harness for boaters, a more stable ladder and an automobile rear view mirror that eliminated blind spots. He held several patents.

In addition to his wife of 48 years, Dr. Epstein is survived by two daughters, Eve Epstein-Burian of Portland, Ore., and Beth Epstein-Hounza of Paris; a sister, Carolyn Koistinen of Northridge, Calif; and two grandchildren. Donations in Dr. Epstein's memory may be made to the MIT Symphony's David Epstein Scholarship Fund, c/o the MIT Department of Music, Room 4-246, Cambridge, Mass. 02139.

BD: Why couldn’t Ravel have at least published an addendum

or erratum?

BD: Why couldn’t Ravel have at least published an addendum

or erratum?