|

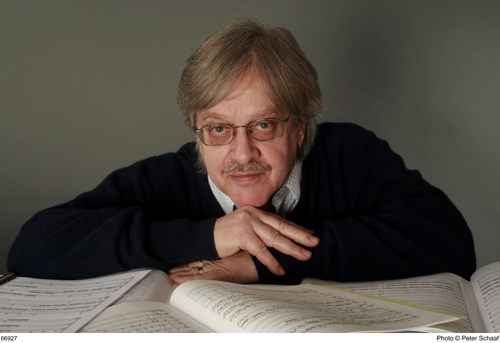

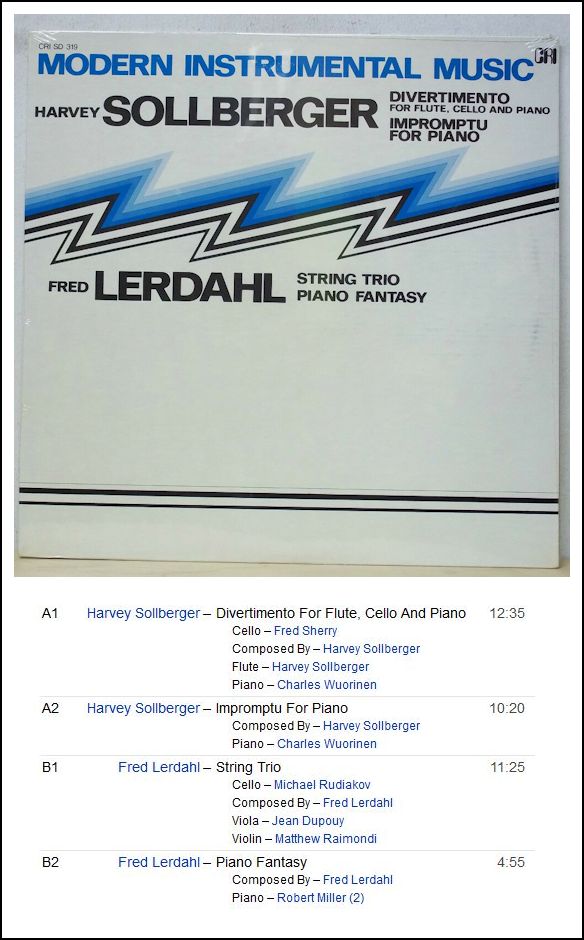

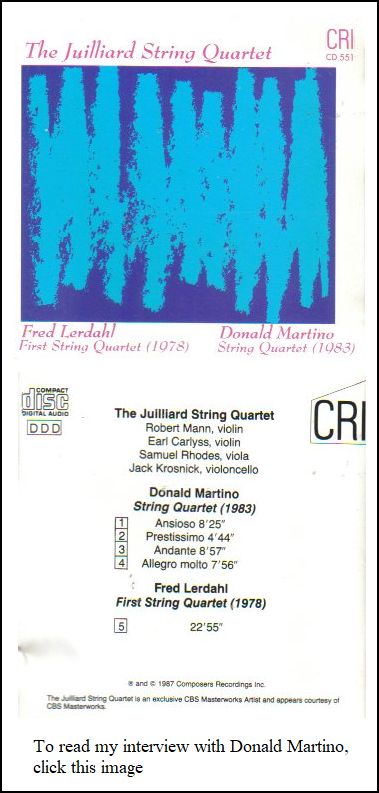

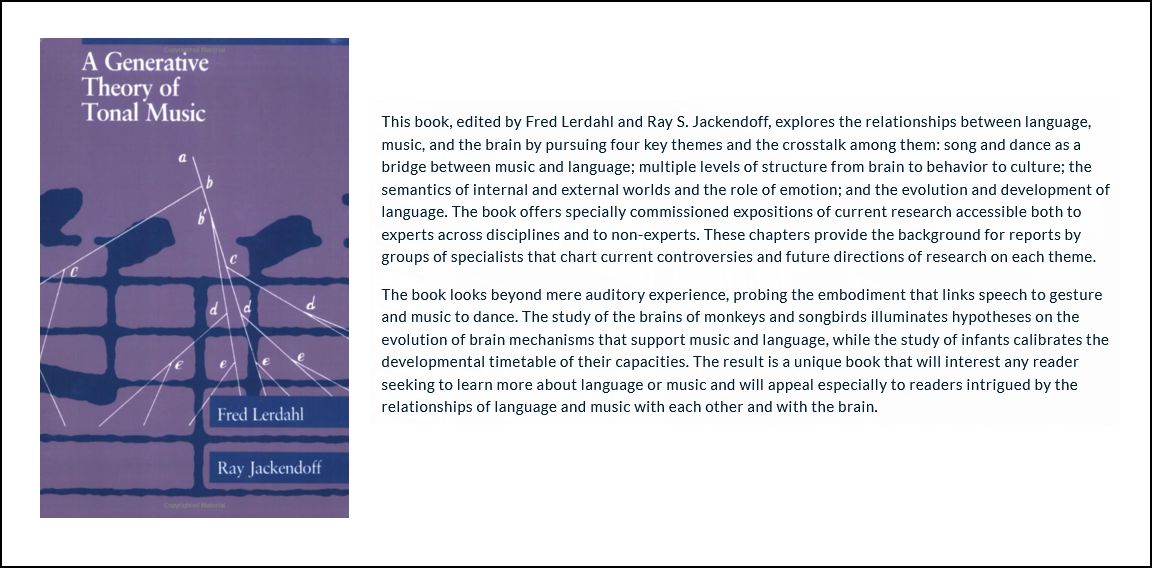

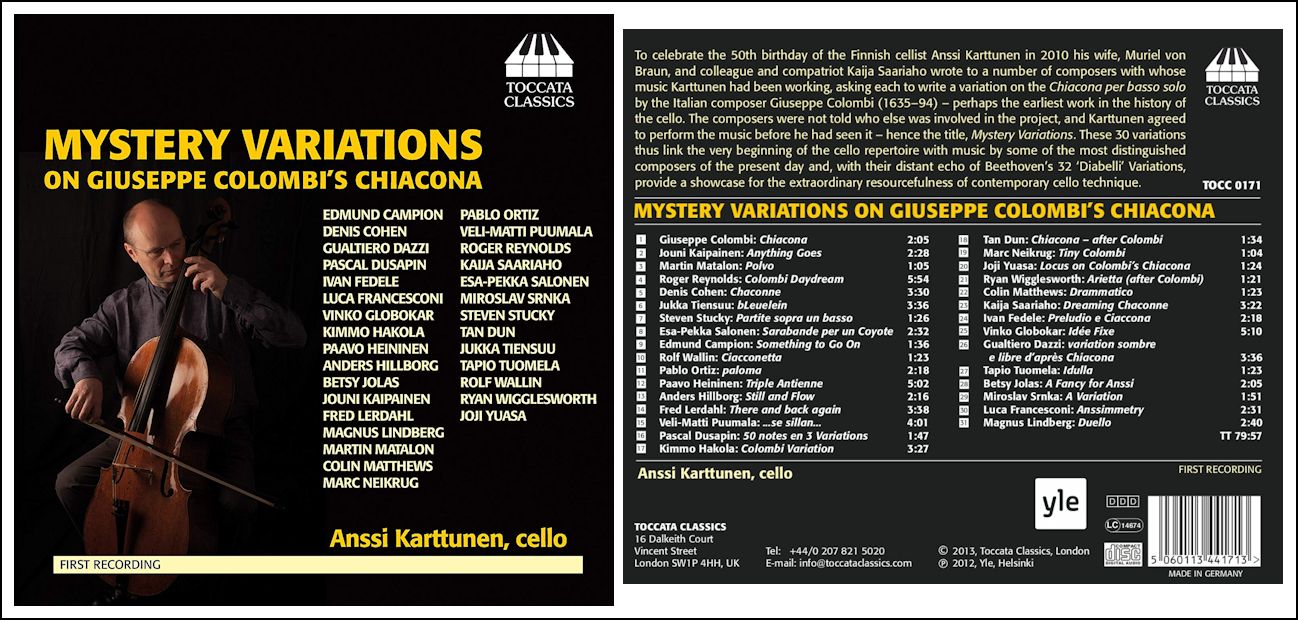

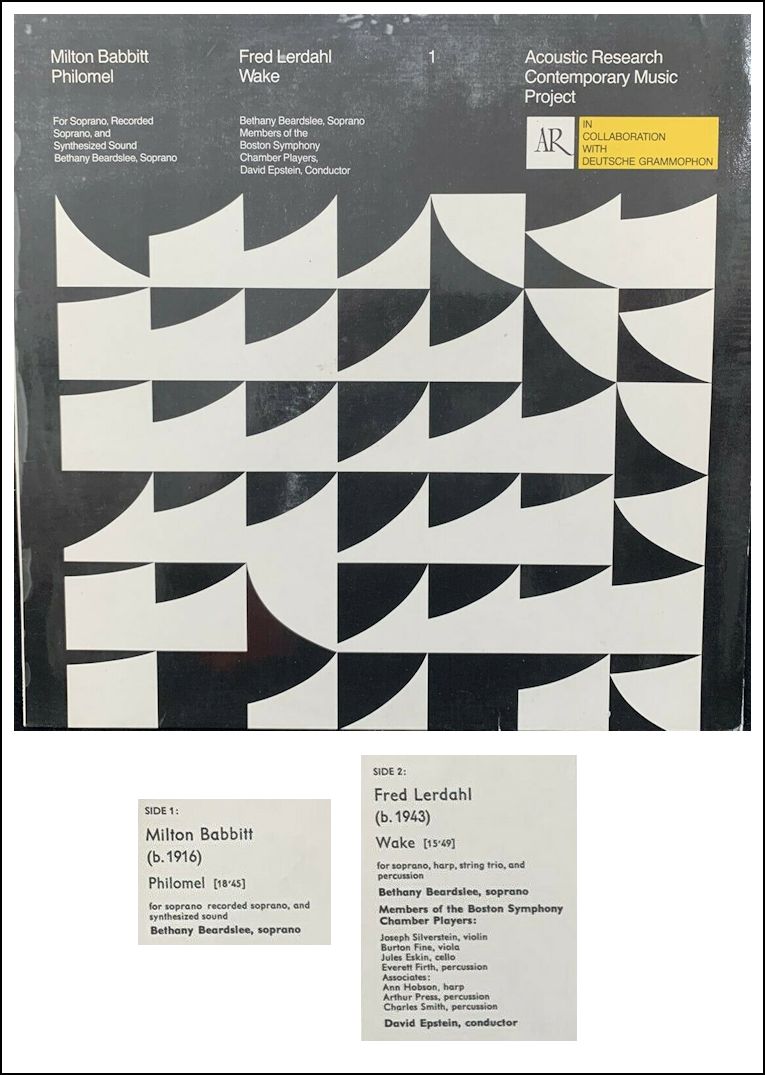

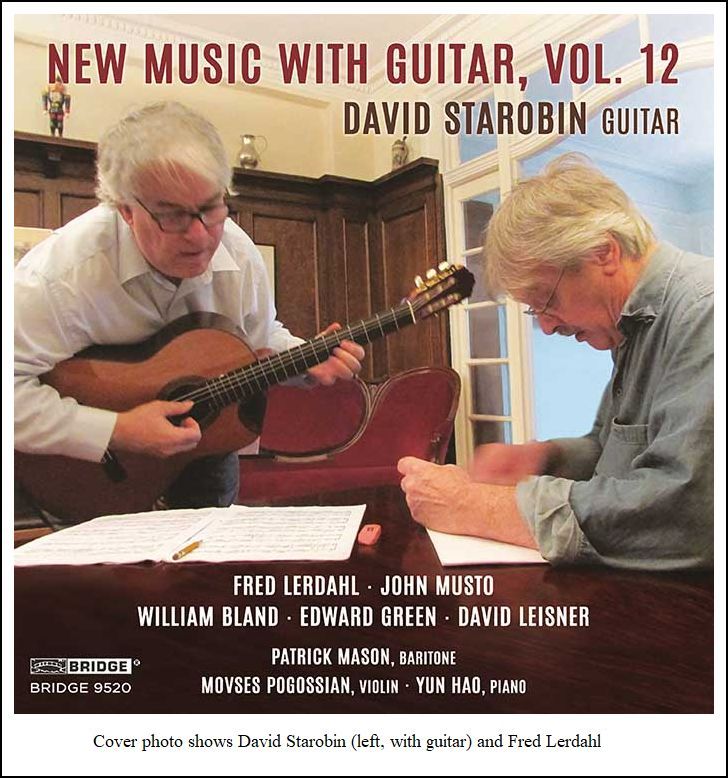

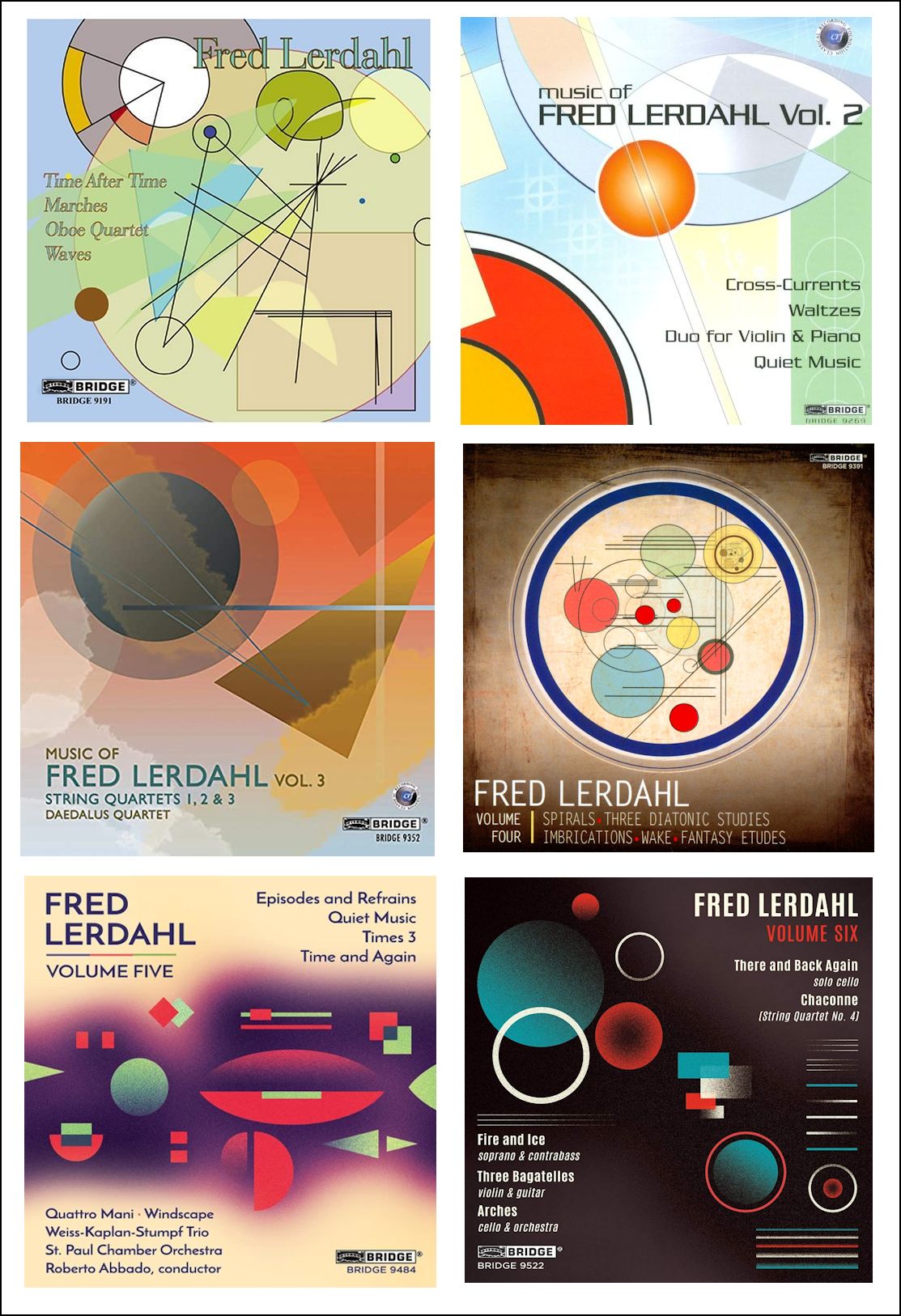

Fred Lerdahl (born March 10, 1943 in Madison, Wisconsin) studied at Lawrence University, Princeton, and Tanglewood. He has taught at UC/Berkeley, Harvard, and Michigan, and since 1991 he has been Fritz Reiner Professor of Music at Columbia University. Commissions have come from the Fromm Foundation, the Koussevitzky Foundation, the Spoleto Festival, National Endowment for the Arts, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, the Library of Congress, Chamber Music America, and others. Among the organizations that have performed his works are the New York Philharmonic, the Pittsburgh Symphony, the San Francisco Symphony, the Seattle Symphony, the Cincinnati Symphony, the Los Angeles Philharmonic, the American Composers Orchestra, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, Orpheus, the Boston Symphony Chamber Players, the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, eighth blackbird, Speculum Musicae, Collage, Argento, Talea, the Peabody Trio, the Juilliard Quartet, the Pro Arte Quartet, the Daedalus Quartet, Ensemble XXI, Lontano, and the Venice Biennale. He has been in residence at the Marlboro Music Festival, IRCAM, the Wellesley Composers Conference, the American Academy in Rome, the Bowdoin Summer Music Festival, the Yellow Barn Music Festival, the Beijing Modern Music Festival, the Etchings Festival, the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra, and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Lerdahl’s music has been commercially recorded on several labels and Bridge Records has established “The Music of Fred Lerdahl” portrait series. His seminal book A Generative Theory of Tonal Music, co-authored with linguist Ray Jackendoff, is a founding document for the growing field of the cognitive science of music. His subsequent book, Tonal Pitch Space, won the 2003 distinguished book award from the Society for Music Theory and an ASCAP-Deems Taylor award. A third book, Composition and Cognition, based on his 2011 Bloch Lectures at UC/Berkeley, brings together his dual activity as composer and theorist. In 2010 Lerdahl was honored with membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Three of his works composed since 2000—Time after Time for chamber ensemble, the Third String Quartet, and Arches for cello and chamber orchestra—have been finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in music. |

BD: Does the theory help out with the composing?

BD: Does the theory help out with the composing? BD: You get a lot of commissions.

How do you decide which one’s you’ll accept, and which ones you’ll turn

down?

BD: You get a lot of commissions.

How do you decide which one’s you’ll accept, and which ones you’ll turn

down? Lerdahl: [Thinks a moment] That’s an impossible

question to answer because it’s important to go with what one is. But,

at the same time, one always strives for certain things artistically.

I want to write music that has a beautiful form, that’s beautifully written

for the instruments, and that is on one level very accessible, and on

other levels has all kinds of things that people keep discovering. It

should be music that’s both formally very precise and very passionate.

Lerdahl: [Thinks a moment] That’s an impossible

question to answer because it’s important to go with what one is. But,

at the same time, one always strives for certain things artistically.

I want to write music that has a beautiful form, that’s beautifully written

for the instruments, and that is on one level very accessible, and on

other levels has all kinds of things that people keep discovering. It

should be music that’s both formally very precise and very passionate.

Lerdahl: Nowadays, music is very confusing because the

avant-garde no longer exists in any meaningful sense, the way that it did

from Wagner to Stockhausen, for example, where there was a cutting edge

that could more or less be agreed upon. There were advances people

set down that seemed coherent in terms of the cultures as a whole.

But when you keep innovating, after a while anything becomes possible, and

that’s what happened to the musical language. By around 1960 with

John Cage, and Stockhausen,

and many others, it was no longer clear how music should progress.

Boulez is a very good example in this respect. He really lost his

direction, his path into the music of the future about that time, which

was when he concentrated more and more on conducting. I’ve often

thought that he had to create IRCAM, his contemporary music center in Paris

— where I’ve spent a lot of time, actually

— because he was seeking a technological solution

to the aesthetic impasse of the avant-garde. In other words, if

there’s no way to progress in any obvious way in terms of musical language,

when the twelve-tone idea seems to have exhausted itself, then one seeks

the solution through new sounds that are only possible with the new technology.

So, it’s not at all clear how music is progressing. My own feeling

is that the new technology is and will become more and more important to

music. This will include computer music in all its forms, which are

not just the pure direct synthesis anymore, but all kinds of interactive

programs with live instruments, and sound-playing, and manipulation of

sound samples, and so on.

Lerdahl: Nowadays, music is very confusing because the

avant-garde no longer exists in any meaningful sense, the way that it did

from Wagner to Stockhausen, for example, where there was a cutting edge

that could more or less be agreed upon. There were advances people

set down that seemed coherent in terms of the cultures as a whole.

But when you keep innovating, after a while anything becomes possible, and

that’s what happened to the musical language. By around 1960 with

John Cage, and Stockhausen,

and many others, it was no longer clear how music should progress.

Boulez is a very good example in this respect. He really lost his

direction, his path into the music of the future about that time, which

was when he concentrated more and more on conducting. I’ve often

thought that he had to create IRCAM, his contemporary music center in Paris

— where I’ve spent a lot of time, actually

— because he was seeking a technological solution

to the aesthetic impasse of the avant-garde. In other words, if

there’s no way to progress in any obvious way in terms of musical language,

when the twelve-tone idea seems to have exhausted itself, then one seeks

the solution through new sounds that are only possible with the new technology.

So, it’s not at all clear how music is progressing. My own feeling

is that the new technology is and will become more and more important to

music. This will include computer music in all its forms, which are

not just the pure direct synthesis anymore, but all kinds of interactive

programs with live instruments, and sound-playing, and manipulation of

sound samples, and so on. BD: If you didn’t have to theorize, and if you didn’t

have to teach, would you spend all of your time composing? And,

if so, would that be enough?

BD: If you didn’t have to theorize, and if you didn’t

have to teach, would you spend all of your time composing? And,

if so, would that be enough?

© 1992 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on May 16, 1992. Portions were broadcast on WNIB the following year, and again in 1998; on WNUR in 2006, 2009, and 2017; and on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2007. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.