|

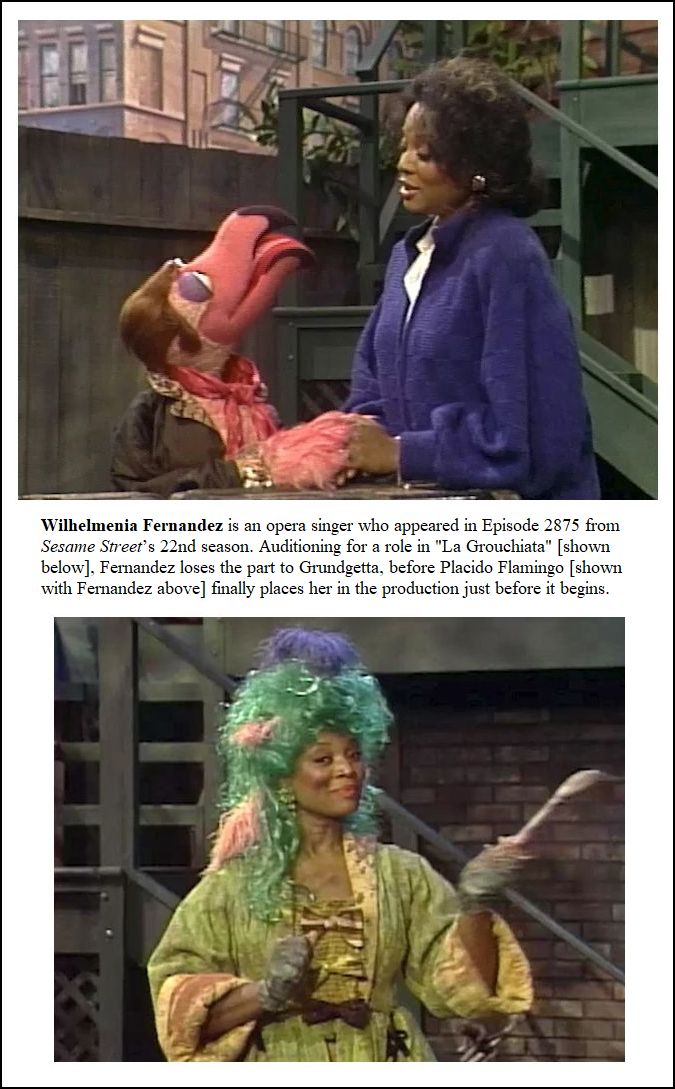

Wilhelmenia Fernandez was born in Philadelphia on January 1, 1949. Her early training was at the Philadelphia Academy of Vocal Arts, followed by a scholarship at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. Her operatic debut was as Bess in Porgy and Bess, for Houston Grand Opera, in a production which toured both the U.S. and Europe. She appeared in the 1981 film Diva by French director Jean-Jacques Beineix. She made her début in Paris as Musetta in La bohème

(with Plácido Domingo and Dame Kiri Te Kanawa), and

at the New York City Opera in the same role in 1982. Since then she

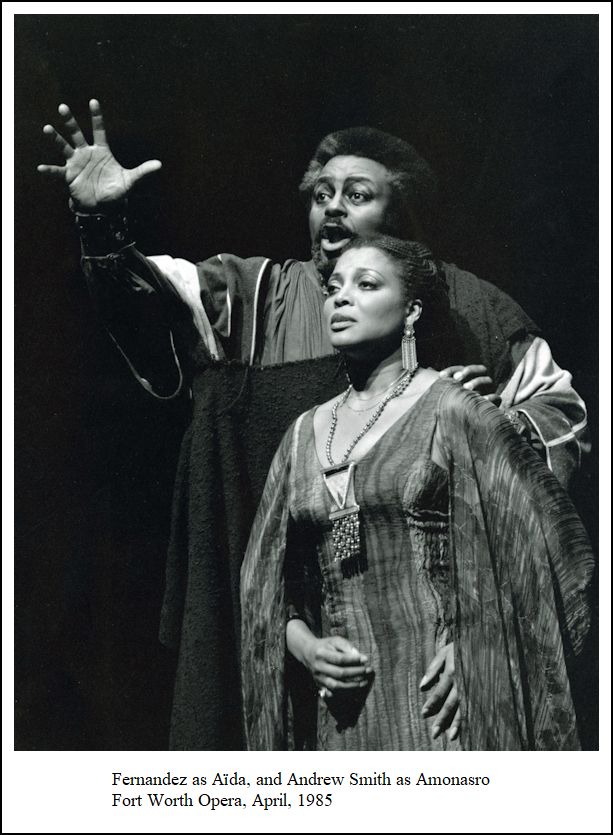

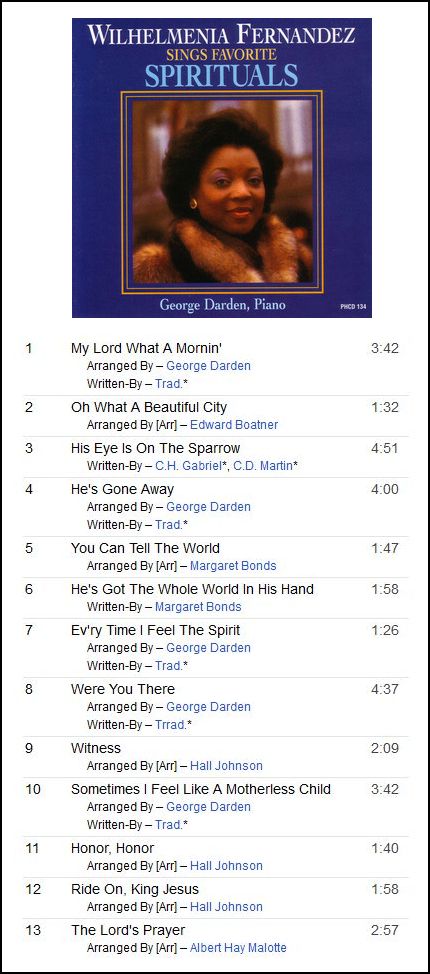

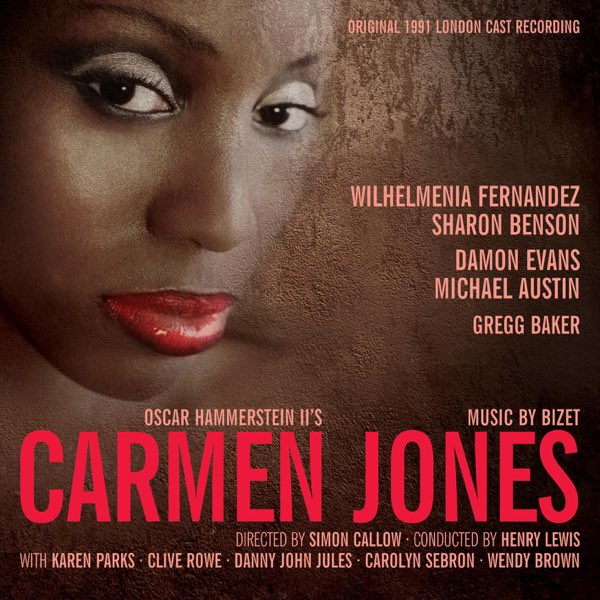

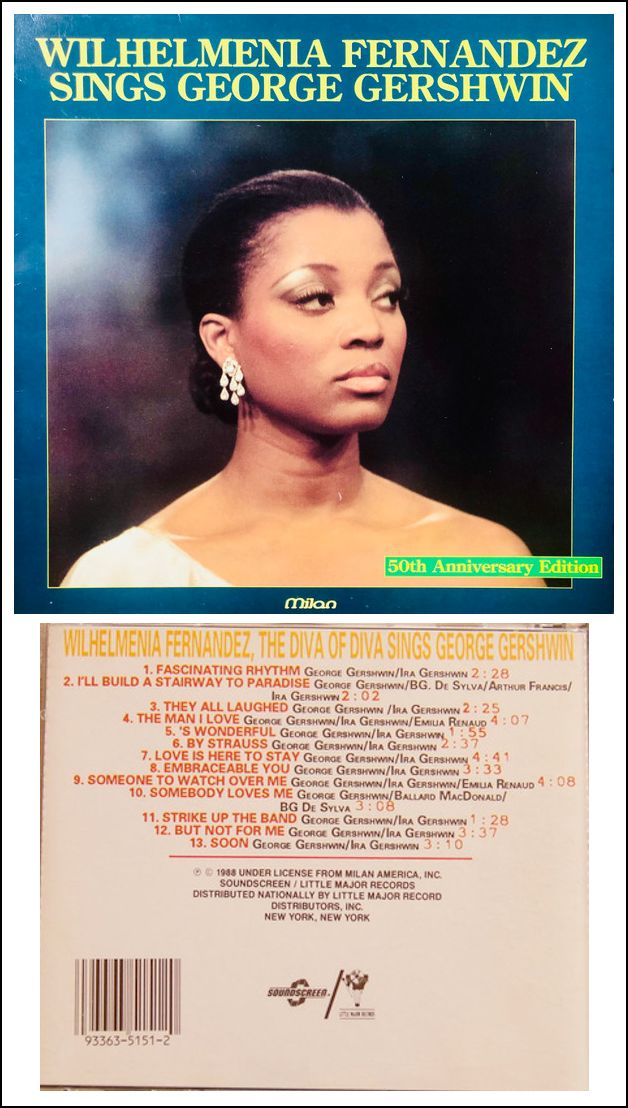

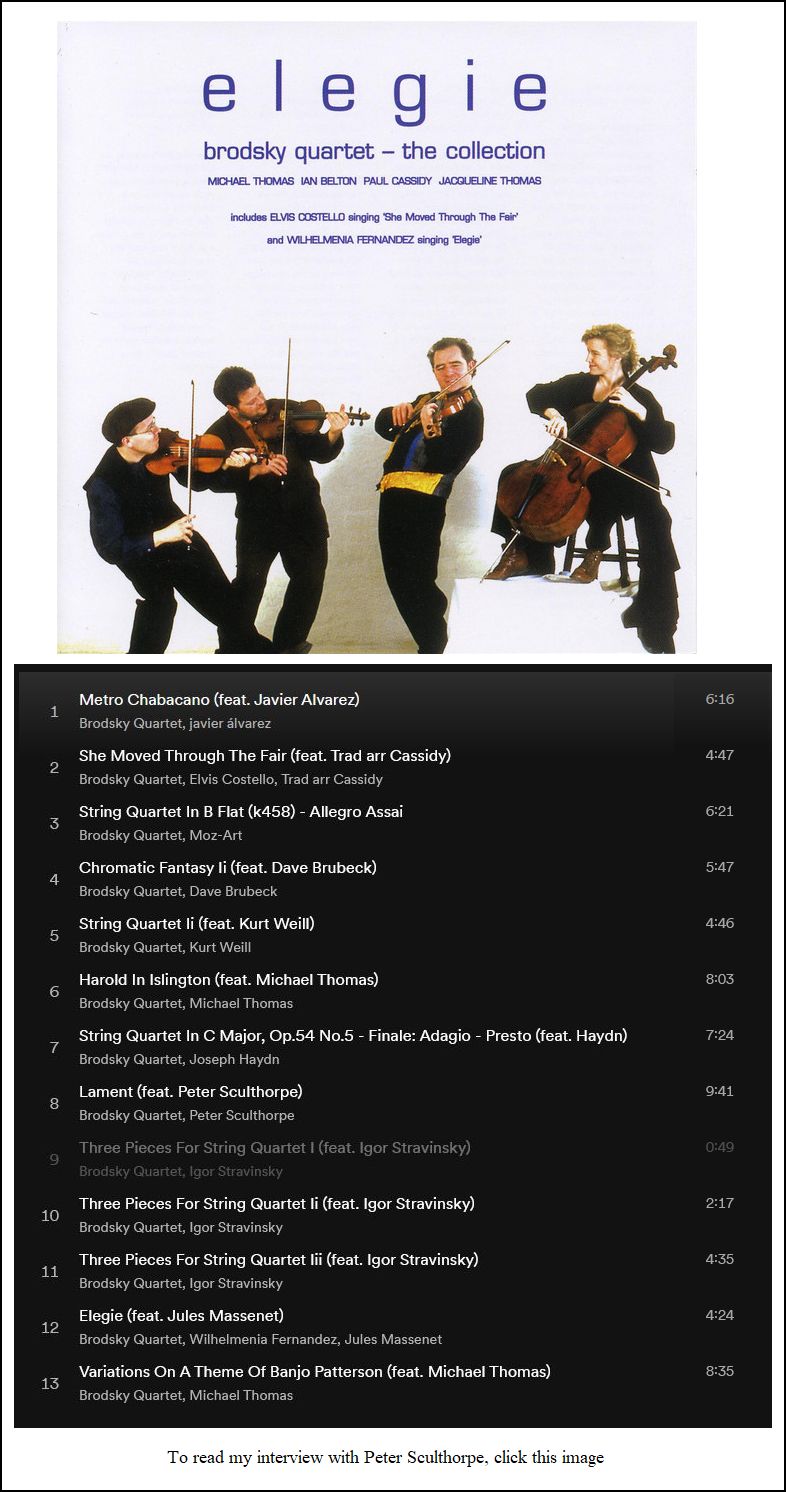

has sung in operas and recitals in cities all over the world. Her more notable roles have been the title roles in Carmen, Carmen Jones (for which she received the Laurence Olivier Theatre Award in 1992 as Best Actress in a Musical), and Aïda (a role she has performed in Luxor and at the Egyptian pyramids). She has also made recordings of George Gershwin songs and of Negro spirituals. Besides Diva, she performed on the soundtrack of Someone to Watch Over Me. == Names which are links on this page refer

to my interviews elsewhere on my website. BD

|

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago, on October 9, 1987. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1994 and 1999. This transcription was made in 2022, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.