|

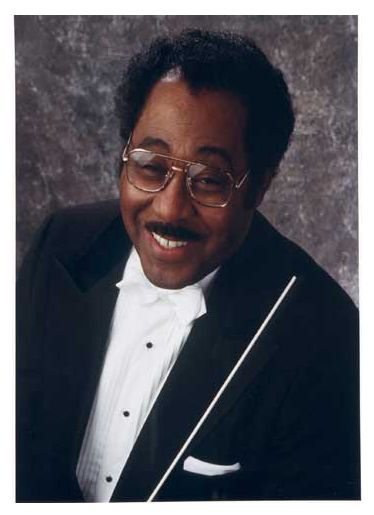

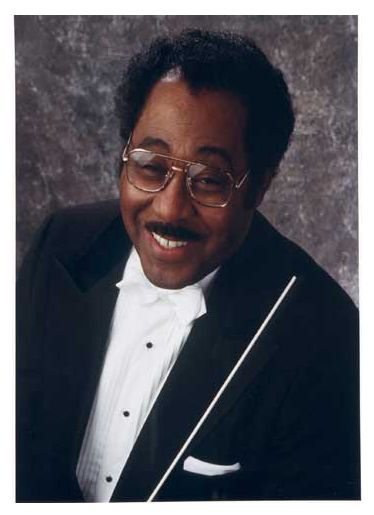

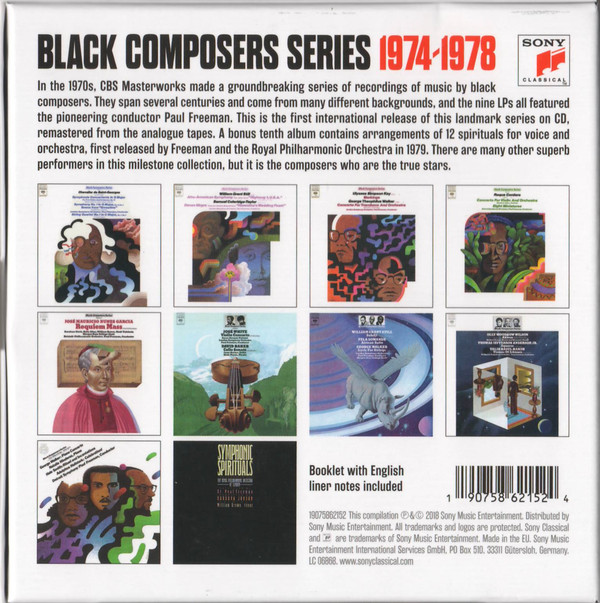

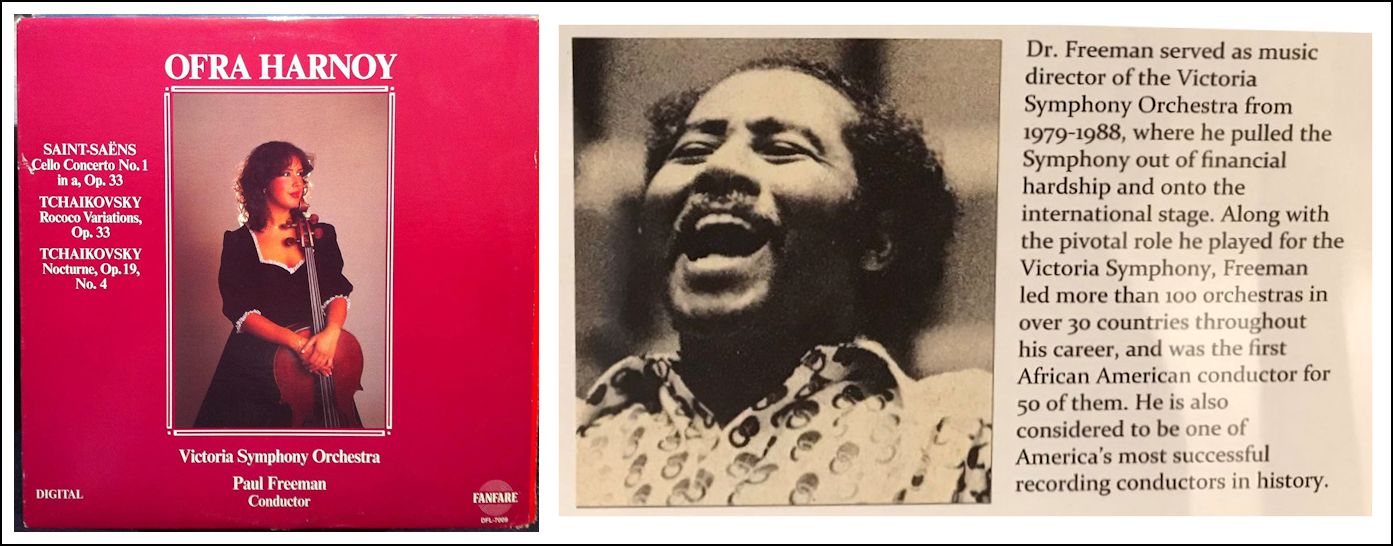

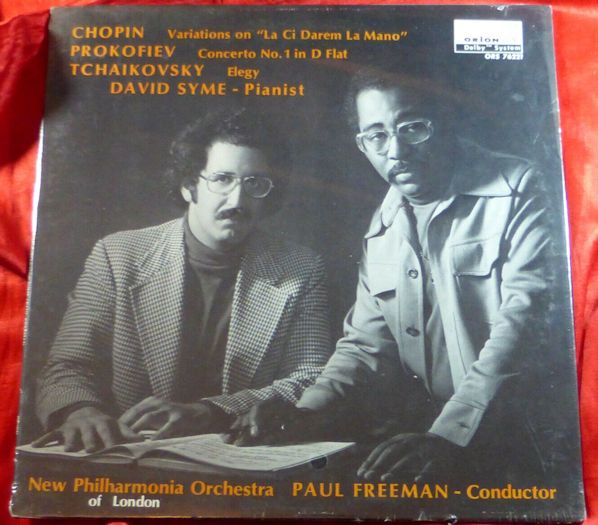

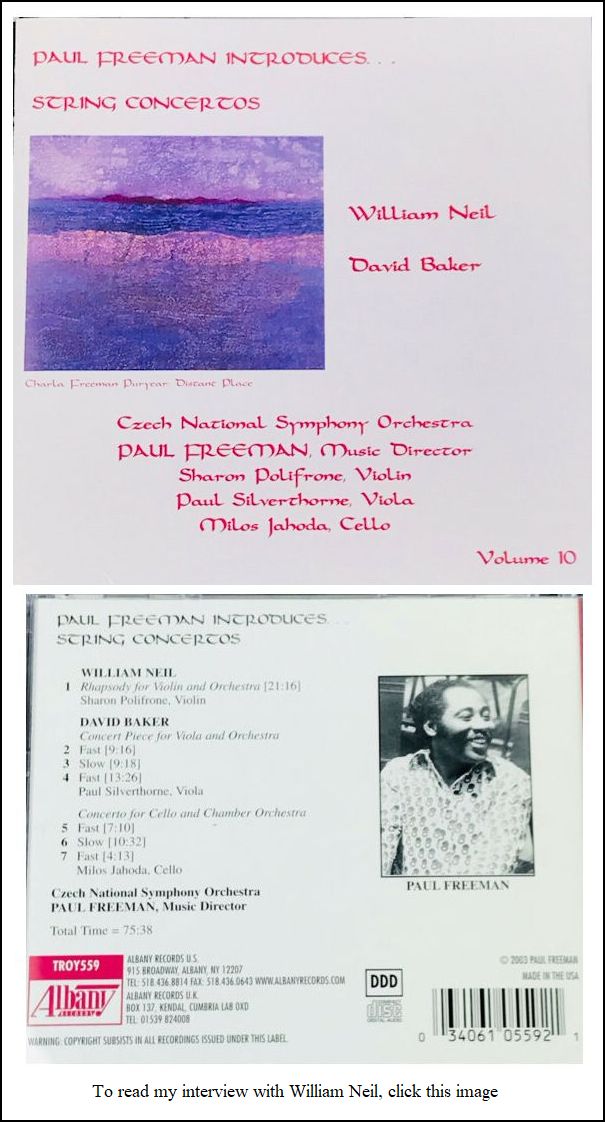

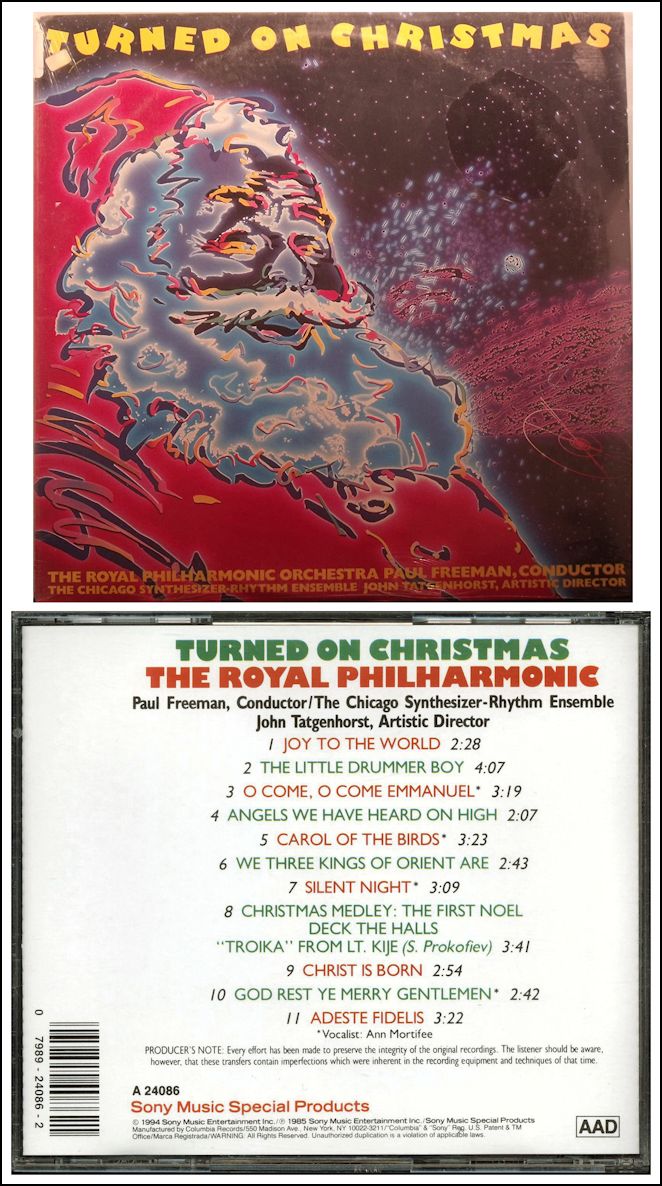

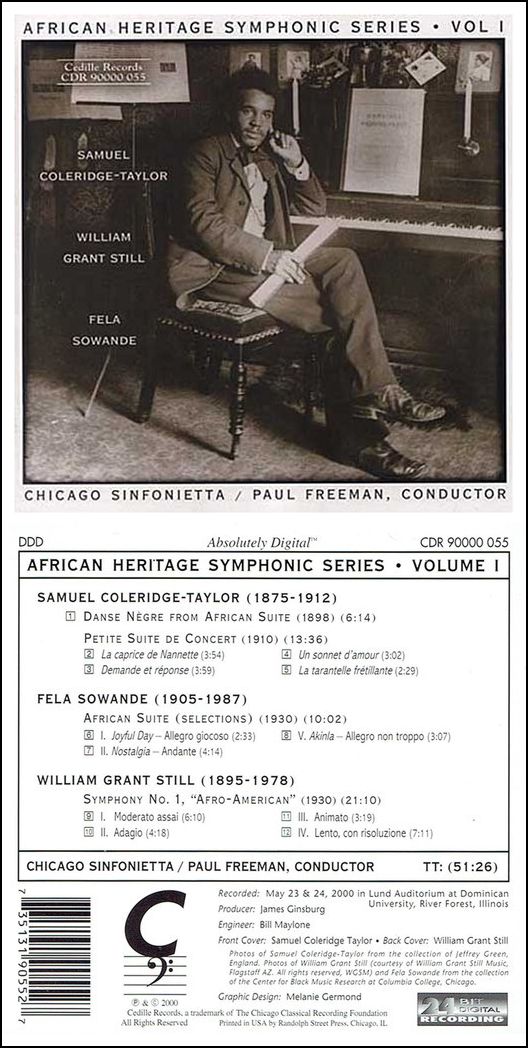

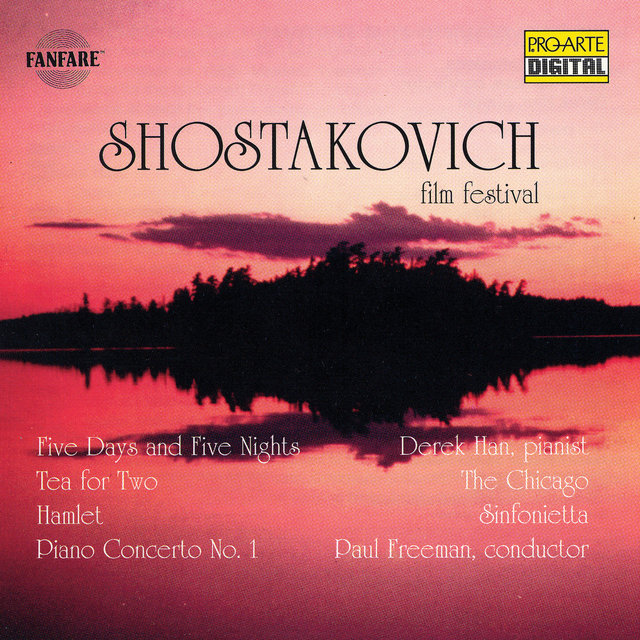

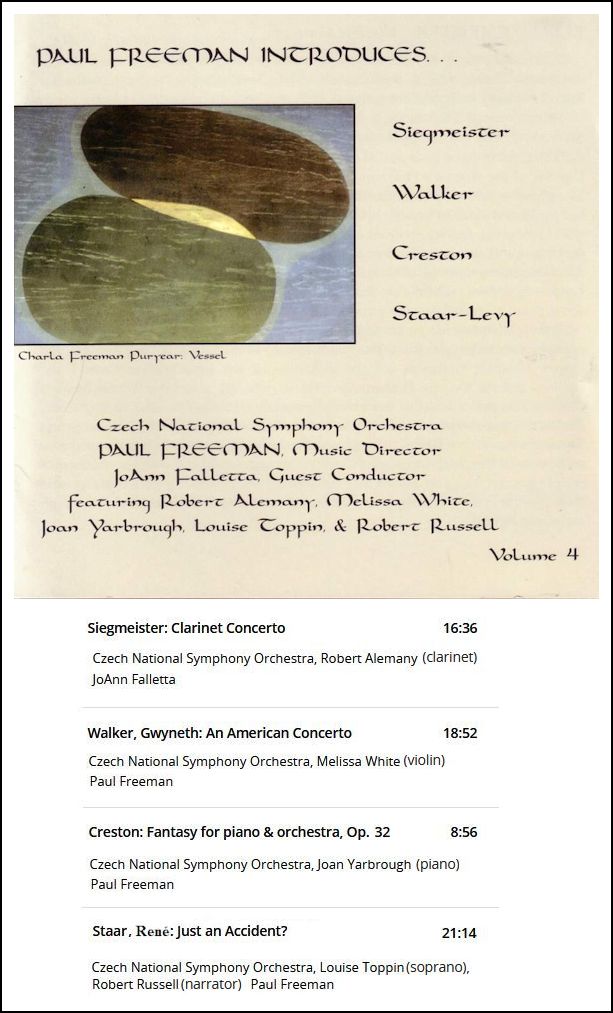

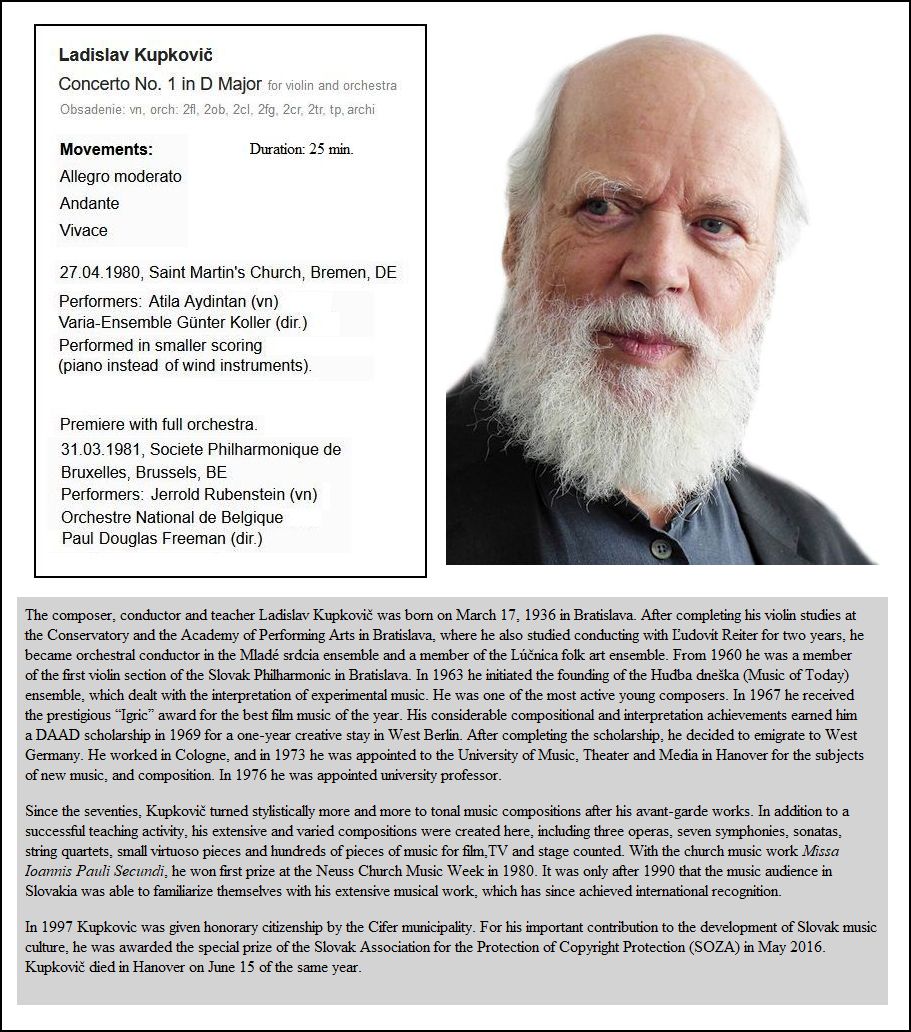

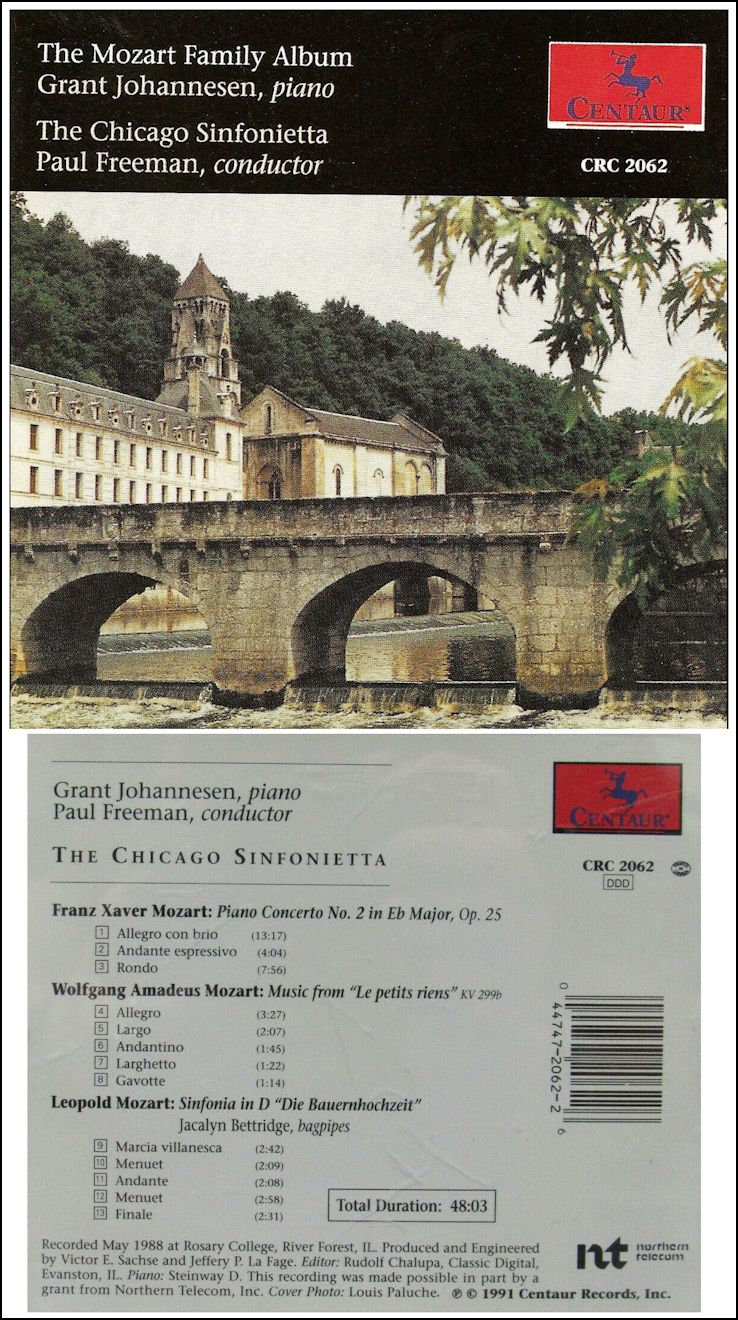

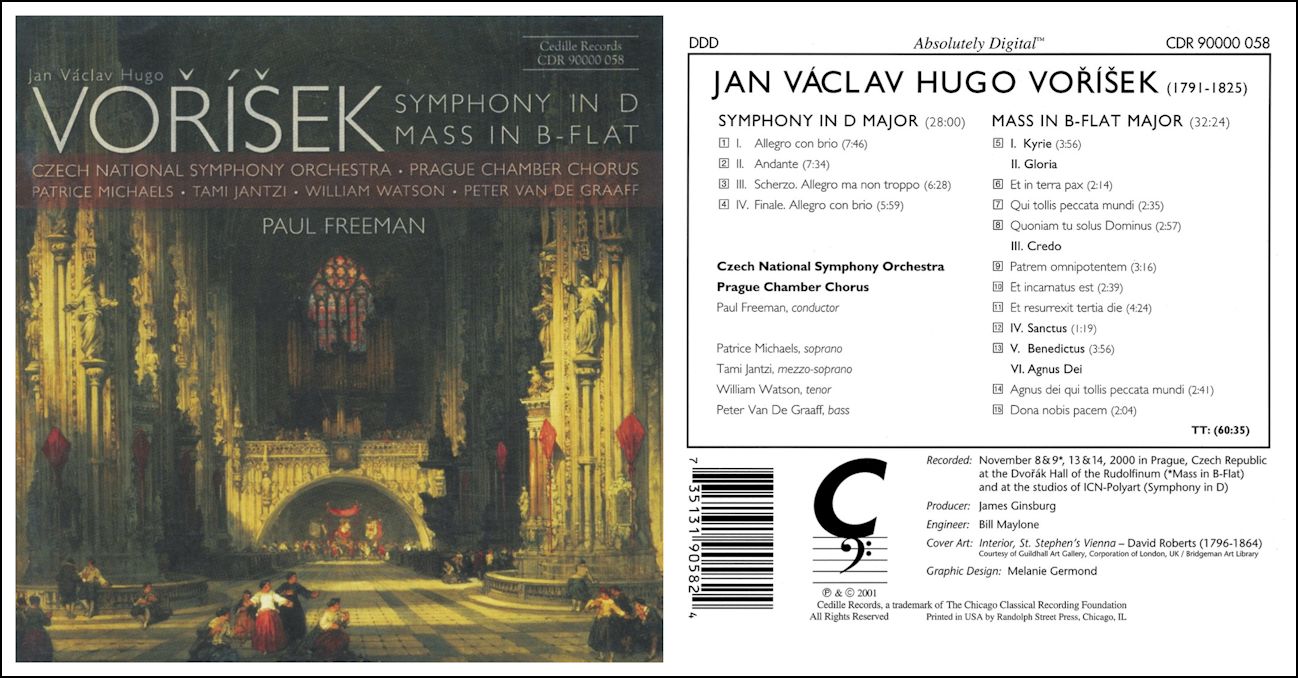

Paul Douglas Freeman (January 2, 1936 – July 21, 2015) was a conductor, composer, and founder of the Chicago Sinfonietta. Freeman earned bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees from the Eastman School of Music. A Fulbright Scholarship enabled him to study for two years at the Hochshule für Musik (University for Music) in Berlin, Germany with Ewald Lindemann. He later studied conducting with Pierre Monteux at the American Symphony Orchestra. While pursuing graduate studies at Eastman, Freeman began his conducting

career as the music director of the Opera Theatre of Rochester

for six years. He then held posts as associate conductor of the Dallas

Symphony Orchestra from 1968-1970 and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra

from 1970-1979. These were followed by a stint as principal guest

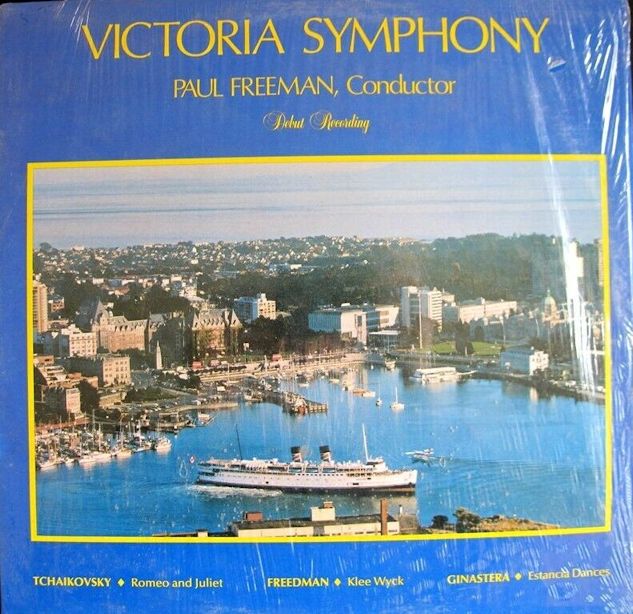

conductor of the Helsinki Philharmonic. From 1979 to 1988, he served

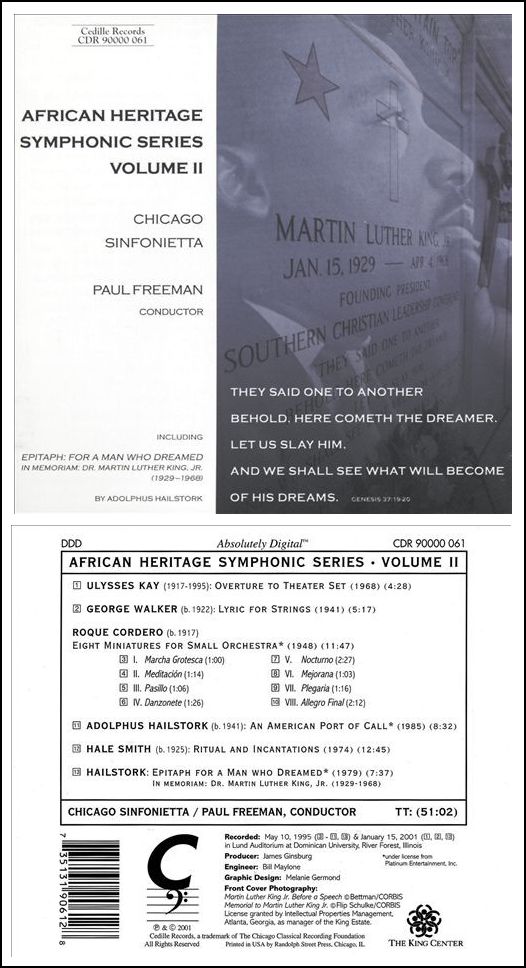

as music director of the Victoria Symphony in Canada. In 1987, he founded the Chicago Sinfonietta of which he remained

the Musical Director until his retirement in 2011. Concurrently

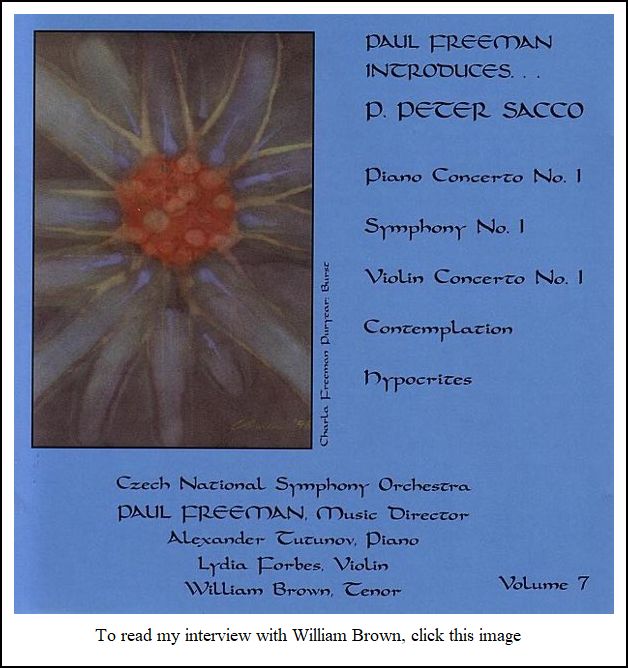

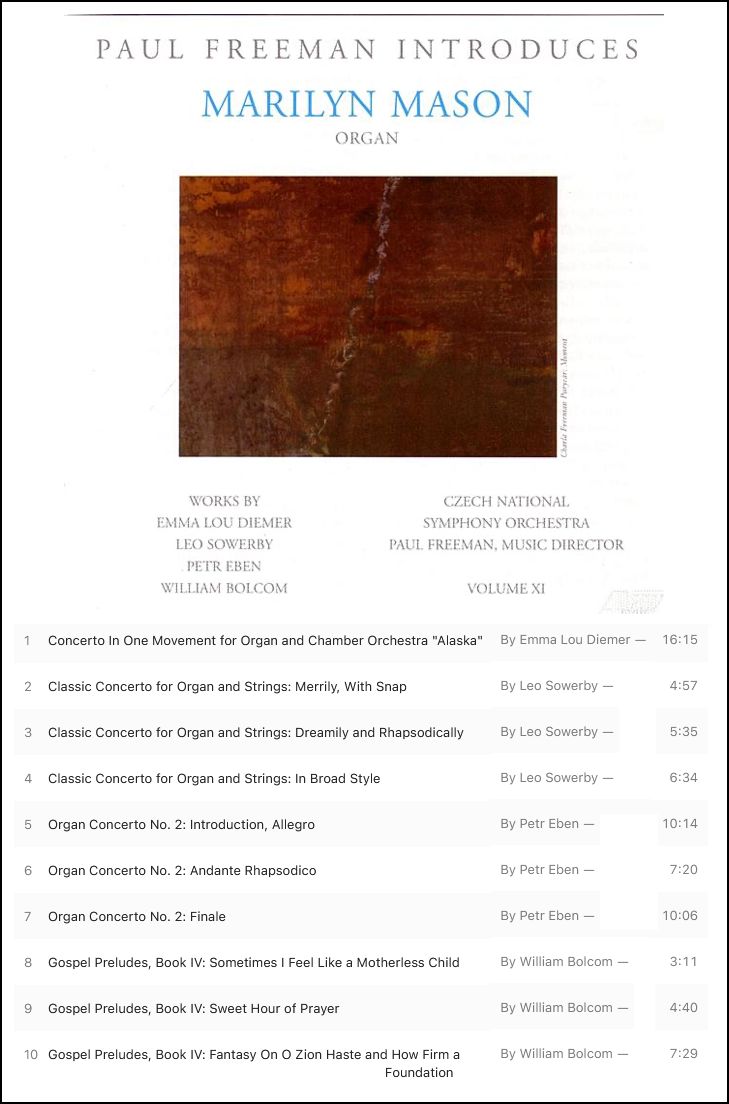

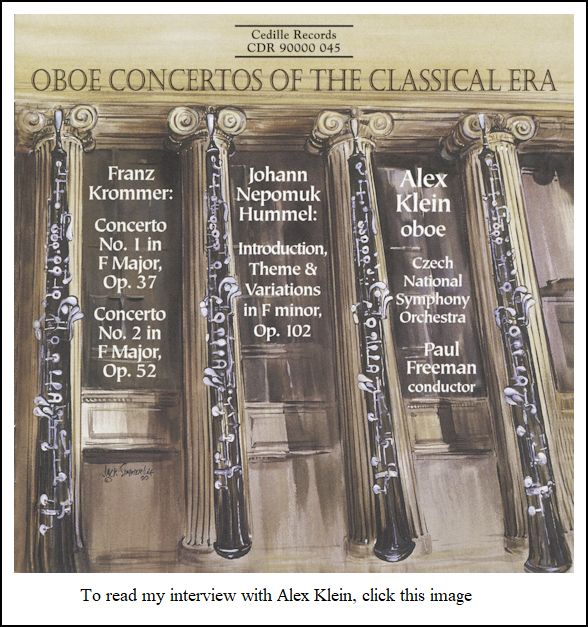

to his time with the Chicago Sinfonietta, he held the post of music

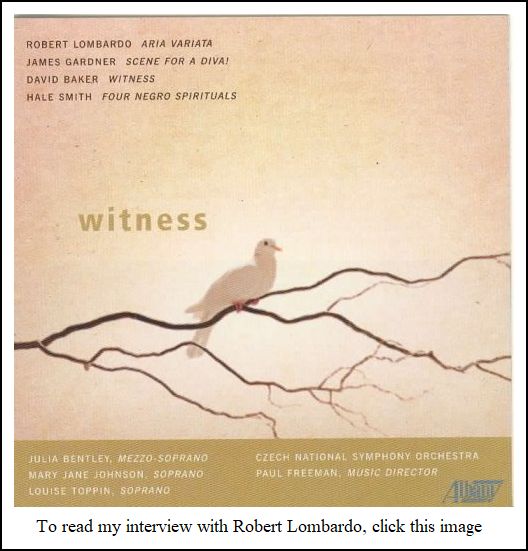

director and chief conductor of the Czech National Symphony Orchestra

in Prague since 1996. Following his retirement from the Chicago

Sinfonietta in 2011, he was named Emeritus Music Director of the orchestra. [To read a more detailed biography, click HERE.] |

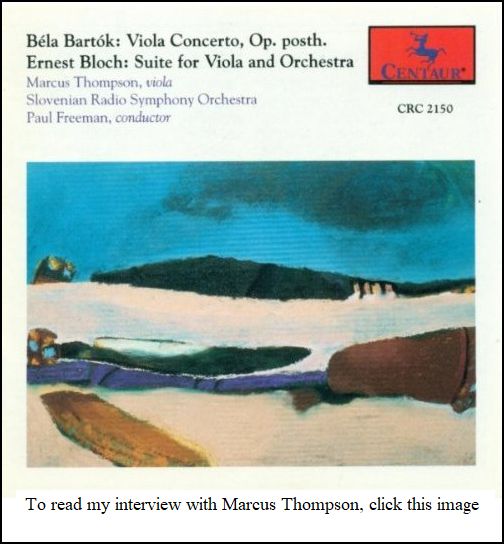

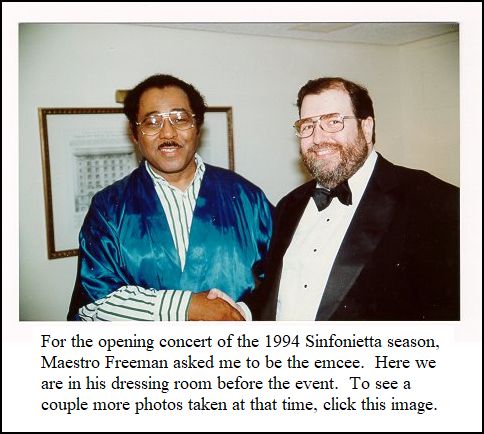

It was my great privilege to

interview Paul Freeman on three occasions, in 1986, 1988,

and 1995. Within the topic of Classical Music, the discussions

ranged far and wide, and included his insights on the situation

faced by black performers and composers. He also spoke

of specific programs which were coming up, and while they,

of course, are now part of history, it goes to show how he regarded

certain styles, and built programs that were interesting and

yet not off-putting.

It was my great privilege to

interview Paul Freeman on three occasions, in 1986, 1988,

and 1995. Within the topic of Classical Music, the discussions

ranged far and wide, and included his insights on the situation

faced by black performers and composers. He also spoke

of specific programs which were coming up, and while they,

of course, are now part of history, it goes to show how he regarded

certain styles, and built programs that were interesting and

yet not off-putting. Freeman: Well, I suppose

that’s possible.

Freeman: Well, I suppose

that’s possible. BD: They would rather

hear Beethoven, Haydn, and Brahms?

BD: They would rather

hear Beethoven, Haydn, and Brahms?| Calvin Eugene Simmons (April 27, 1950

– August 21, 1982) was an American symphony orchestra conductor.

After working as assistant conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic under Zubin Mehta, Simmons became Music Director of the Oakland Symphony Orchestra at age 28. He led the orchestra for four years, and continued to conduct the Los Angeles Philharmonic, both at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion and at the Hollywood Bowl. He would support Carmen McRae singing jazz one night, then conduct William Walton or Holst's The Planets a night or two later. He was the first African-American to be named conductor of a major U.S. symphony orchestra, and was a frequent guest conductor with some of the nation's major opera companies and orchestras (such as the Philadelphia Orchestra). He was the Music Director at the Ojai Music Festival in 1978. He made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera on 20 December 1978, aged 28, conducting Engelbert Humperdinck's Hansel and Gretel. He returned the following season for the same opera, of which he conducted a total of 18 performances. He was on the musical staff at Glyndebourne from 1974 to 1978, and conducted the Glyndebourne Touring Opera, including Così fan tutte in 1975. He collaborated with the British director Jonathan Miller on a celebrated production of Mozart's Così fan tutte at the Opera Theater of St. Louis (USA) shortly before his death. He remained active at the San Francisco Opera for all his adult life, first as a repetiteur and then as a member of the conducting staff. He made his formal debut conducting Giacomo Puccini's La Bohème with Ileana Cotrubas. His later work on a production of Dmitri Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District drew national attention. In 1979 he conducted the premiere of Menotti's La Loca at San Diego. His final concerts were three performances of the Requiem of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in the summer of 1982 with the Masterworks Chorale and the Midsummer Mozart Festival Orchestra. Simmons died in a canoeing accident at age 32 near Lake Placid in New York. After a large public funeral at San Francisco's Grace Cathedral, he was buried in Cypress Lawn Memorial Park in Colma, California.The Oakland Symphony Orchestra was reorganized in July 1988 as the Oakland East Bay Symphony Orchestra, and Simmons was honored by the naming of the Calvin Simmons Theatre at the Henry J. Kaiser Convention Center in Oakland, California. The Calvin Simmons Middle School in Oakland was named for him, but has since changed its name to United For Success Academy. Simmons is also the namesake of the grand ballroom of the Oakland Marriott Hotel. His death inspired Lou Harrison to compose Elegy, To The Memory Of Calvin Simmons; Michael Tippett to compose The Blue Guitar, a sonata for solo guitar; and Robert Hughes to compose Sop'o muerte se cande, for high tenor and orchestra (1983, 2013). John Harbison wrote Exequien for Calvin Simmons. (Simmons conducted Harbison's Violin Concerto shortly before his death.) |

|

In 1980, he won first prize in the Hans Swarovsky International

Conductors Competition in Vienna, Austria and became Assistant Conductor

of the St Louis Symphony Orchestra under Leonard Slatkin. His

operatic debut was in 1982 at the Vienna State Opera

in Mozart’s “The Abduction from the Seraglio”. In 1986,

Sir Georg Solti chose him to become the Assistant Conductor

of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra a position he held for five

years under both Georg Solti and Daniel Barenboim.

He became music director of the Oakland East Bay Symphony

in 1990. Maestro Morgan serves as artistic director of

the Oakland Youth Orchestra, and was the music director of

the Sacramento Philharmonic Orchestra (and the Sacramento

Opera) from 1999-2015 and artistic director of Festival Opera

in Walnut Creek, California for more than 10 seasons. He

teaches the graduate conducting course at the San Francisco Conservatory

of Music and is Music Director at the Bear Valley Music Festival

in California. In 2002 and 2003 he taught conducting at

the Tanglewood Music Center and has led conducting workshops around

the country. As Stage Director he has led productions of the Bernstein Mass at the Oakland East Bay Symphony and a modern staging of Mozart’s Don Giovanni at Festival Opera, where he has also staged Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Gounod’s Faust. As a chamber musician (piano) he has appeared on the Chamber Music Alive series in Sacramento as well as the occasional appearance in the Bay Area. As a guest conductor he has appeared with most of America’s major orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, National Symphony, Baltimore Symphony, Philadelphia Orchestra, Atlanta Symphony, Alabama Symphony, Houston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Seattle Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, Pittsburgh Symphony, Detroit Symphony, Vancouver Symphony, Winnipeg Symphony, Edmonton Symphony and Omaha Symphony. He was Music Advisor to the Peoria during their most recent conductor search. As conductor of opera he has performed with St. Louis Opera Theater, New York City Opera (in New York and on tour), and the Staatsoper in Berlin. Abroad he has conducted orchestras in Europe, South America, the Middle East (Israel and Egypt) and even the Kimbaguiste Symphony Orchestra in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. In 2005 he was honored by the San Francisco Chapter of The Recording Academy with the 2005 Governor’s Award for Community Service. On the opposite coast, the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) chose Morgan as one of its five 2005 Concert Music Award recipients. ASCAP further honored Oakland East Bay Symphony in 2006 with its Award for Adventurous Programming. The San Francisco Foundation honored him with one of its Community Leadership Awards and he received an Honorary Doctorate from Holy Names University in Oakland,CA. In 2014 he gave a TEDx Talk and was featured by Musical America as one of their “Profiles of Courage”. He has served on the boards of the League of American Orchestras

and the International House at the University

of California, Berkeley, and the National Guild of Community

Schools of the Arts. Currently he is on the boards of

the Purple Silk Music Education Foundation, the Oaktown

Jazz Workshops, and the Mathematical Sciences Research Institute.

== Biography above is from the John Gingrich

Management website.

== The item below is from Georgia Voice, March 15, 2013. == The last item is from various obituaries.

Morgan is homosexual. He has said that "Being a

classical musician, being a conductor, being black,

being gay – all of these things put you on the outside,

and each one puts you a little further out than the last one"

and that "you get accustomed to constructing your own world

because there are not a lot of clear paths to follow and not

a lot of people that are just like you".

For the last seven years of his life Morgan was on daily kidney dialysis. He received a kidney transplant in May 2021, but contracted an infection, and died on August 20, 2021 at the age of 63. |

BD: You just hear the

sound they produce?

BD: You just hear the

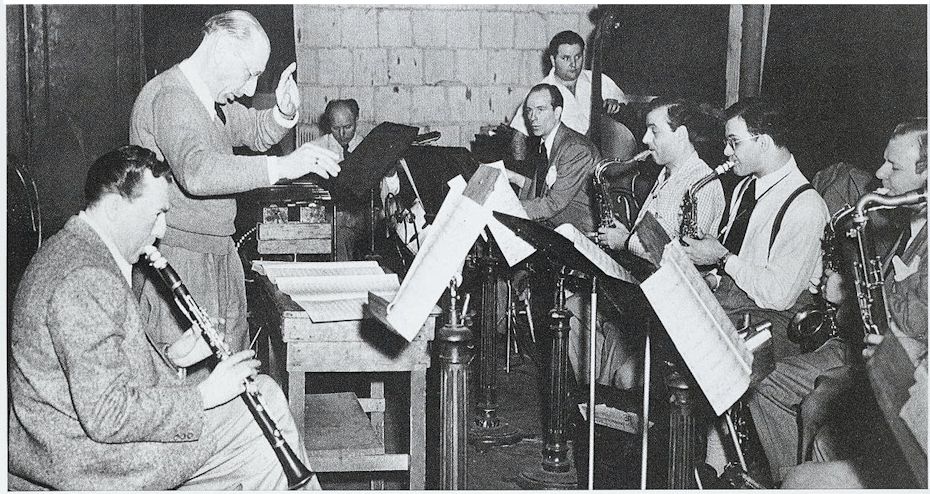

sound they produce?| Igor Stravinsky wrote the Ebony

Concerto in 1945 (finishing the score on December 1) for

the Woody Herman band known as the First Herd. It is one in a series

of compositions commissioned by the bandleader/clarinetist featuring

solo clarinet, and the score is dedicated to him. It was first performed

on March 25, 1946 in Carnegie Hall in New York City, by Woody Herman's

Band, conducted by Walter Hendl. Stravinsky's engagement with jazz dates back to the closing years of the First World War, the major jazz-inspired works of that period being L'histoire du soldat, the Ragtime for eleven instruments, and the Piano-Rag-Music. Although traces of jazz elements, especially blues and boogie-woogie, can be found in his music throughout the 1920s and 1930s, it was only with the Ebony Concerto that Stravinsky once again incorporated features of jazz into a composition on a far-reaching scale. The title was originally suggested to Stravinsky by Aaron Goldmark, of Leeds Music Corporation, who had negotiated the commission and suggested the form it should take. The composer explained that his title does not refer to the clarinet, as might be supposed, but rather to Africa, because "the jazz performers I most admired at that time were Art Tatum, Charlie Parker, and the guitarist Charles Christian. And blues meant African culture to me." The Ebony Concerto is scored for solo clarinet in B♭ and a jazz band consisting of two alto

saxophones in E♭, two tenor saxophones in B♭, baritone saxophone in E♭, three clarinets in B♭ (doubled by first and second alto and

first tenor saxophone players), bass clarinet in B♭ (doubled by second tenor saxophone), horn

in F, five trumpets in B♭, three trombones, piano, harp, guitar,

double bass, and drum set. The horn and harp were additions to the

normal make-up of the Herman band. Stravinsky's original plan was

to include an oboe as well, but this instrument did not survive into

the final version of the score. A typical performance lasts about eleven

minutes.

|

Freeman: Personally, I feel

with the original instruments that we’re going through a phase.

I may be wrong in this, and there may be other musicians

who feel this way, as well as some who feel just the opposite.

The invention of the modern instruments is really something

that I know many people are grateful for, because there are

certain improvements. We are, of course, accustomed

to hearing certain things on modern instruments, and while there’s

a certain authenticity with the old instruments, it’s still quite

alien to many ears. There are certain sacrifices and compromises

of intonation that one has to make in order to achieve what one thinks

is authentic. But also in that program we shall feature

four of our own musicians in the Haydn Sinfonia Concertante

for violin, cello, oboe, and bassoon. We are also performing

the Schoenberg Chamber Symphony No. 2 to bring us into the

Twentieth-century, and Ma Mère l’Oye [Mother Goose]

of Ravel. So, we have a varied program there.

Freeman: Personally, I feel

with the original instruments that we’re going through a phase.

I may be wrong in this, and there may be other musicians

who feel this way, as well as some who feel just the opposite.

The invention of the modern instruments is really something

that I know many people are grateful for, because there are

certain improvements. We are, of course, accustomed

to hearing certain things on modern instruments, and while there’s

a certain authenticity with the old instruments, it’s still quite

alien to many ears. There are certain sacrifices and compromises

of intonation that one has to make in order to achieve what one thinks

is authentic. But also in that program we shall feature

four of our own musicians in the Haydn Sinfonia Concertante

for violin, cello, oboe, and bassoon. We are also performing

the Schoenberg Chamber Symphony No. 2 to bring us into the

Twentieth-century, and Ma Mère l’Oye [Mother Goose]

of Ravel. So, we have a varied program there. BD: As Music Director of the Sinfonietta,

do you decide who you will invite to be soloists?

BD: As Music Director of the Sinfonietta,

do you decide who you will invite to be soloists?

|

From 1917 to 1919 Monteux was the principal conductor of the French repertoire at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. He conducted the Boston Symphony Orchestra (1919–24), Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra (1924–34), Orchestre Symphonique de Paris (1929–38) and San Francisco Symphony (1936–52). In 1961, aged eighty-six, he accepted the chief conductorship of the London Symphony Orchestra, a post which he held until his death three years later. Although known for his performances of the French repertoire, his chief love was the music of German composers, above all Brahms. He disliked recording, finding it incompatible with spontaneity, but he nevertheless made a substantial number of records. Monteux was well known as a teacher. In 1932 he began a conducting class in Paris, which he developed into a summer school that was later moved to his summer home in Les Baux in the south of France. After moving permanently to the US in 1942, and taking American citizenship, he founded a school for conductors and orchestral musicians in Hancock, Maine (L’École Monteux). Among his students in France and America who went on to international fame were Lorin Maazel, Igor Markevitch, Neville Marriner, Seiji Ozawa, André Previn, and David Zinman. The school in Hancock has continued since Monteux's death. |

I was playing clarinet and cello

in the orchestra of L’École

Monteux, where he would have the conducting students

perform. Most of them played orchestral instruments,

and he would sit in the woodwind section of the orchestra,

and often you would hear him make remarks, or sing a line, or

make a motion. Very little of what he said had to be put into

words. So, in other words, you’re just trying to absorb all these

little things, all the interesting things that he said about inner

melodies or inner parts of a given work, much less major things.

One thing I shall never forget that he would say is, “The

right tempo is in the air. One must find it.”

Now, that sounds like a nebulous statement, but what

he’s saying is that so many things go into the makeup of a given

tempo of a given work, of a given movement, of a given section.

Then, finding the right tempo also is a highly personalized

matter. As a result of experience and studying, one determines

how one arrives at the tempo, but the important thing is after you

have determined the tempo that you would like to take for a given

movement or section, the trick is being able to present that in as

convincing a way as possible. I was just thinking of the

Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, which Kurt Masur conducted

with the Chicago Symphony during the month of June. I was

conducting that symphony with the Grant Park Orchestra

during the month of July. Now, I am not going to make

a comparison between the two orchestras, but what I have to

say is that in the finale of the work, more times than not the tempo

is very driving [sings the melody very fast], whereas, Masur

took a much slower tempo [sings the same melody more slowly].

He is convinced that Shostakovich wanted it that way. I

didn’t have the pleasure of meeting Shostakovich personally,

and I don’t feel it that way. It’s not written in the score

that way, so if Shostakovich wanted it that way there’s nothing

wrong with doing it that way — if

you do it convincingly, as Masur did.

I was playing clarinet and cello

in the orchestra of L’École

Monteux, where he would have the conducting students

perform. Most of them played orchestral instruments,

and he would sit in the woodwind section of the orchestra,

and often you would hear him make remarks, or sing a line, or

make a motion. Very little of what he said had to be put into

words. So, in other words, you’re just trying to absorb all these

little things, all the interesting things that he said about inner

melodies or inner parts of a given work, much less major things.

One thing I shall never forget that he would say is, “The

right tempo is in the air. One must find it.”

Now, that sounds like a nebulous statement, but what

he’s saying is that so many things go into the makeup of a given

tempo of a given work, of a given movement, of a given section.

Then, finding the right tempo also is a highly personalized

matter. As a result of experience and studying, one determines

how one arrives at the tempo, but the important thing is after you

have determined the tempo that you would like to take for a given

movement or section, the trick is being able to present that in as

convincing a way as possible. I was just thinking of the

Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, which Kurt Masur conducted

with the Chicago Symphony during the month of June. I was

conducting that symphony with the Grant Park Orchestra

during the month of July. Now, I am not going to make

a comparison between the two orchestras, but what I have to

say is that in the finale of the work, more times than not the tempo

is very driving [sings the melody very fast], whereas, Masur

took a much slower tempo [sings the same melody more slowly].

He is convinced that Shostakovich wanted it that way. I

didn’t have the pleasure of meeting Shostakovich personally,

and I don’t feel it that way. It’s not written in the score

that way, so if Shostakovich wanted it that way there’s nothing

wrong with doing it that way — if

you do it convincingly, as Masur did. Freeman: You are

asking questions that an average commentator doesn’t

ask, so it’s fascinating to me.

Freeman: You are

asking questions that an average commentator doesn’t

ask, so it’s fascinating to me.

BD: Have you gotten

to the point where the audiences trust you, and trust

the Sinfonietta, so it is the Sinfonietta who is the real

soloist and the real draw, and almost no matter what you prepare,

they’re willing to give it a try?

BD: Have you gotten

to the point where the audiences trust you, and trust

the Sinfonietta, so it is the Sinfonietta who is the real

soloist and the real draw, and almost no matter what you prepare,

they’re willing to give it a try?

Toronto based NEXUS is widely recognized as one of the most influential percussion ensembles to have emerged in the post-war period. The New York Times has called the ensemble, “The high priests of the percussion world.” Steve Reich said they are, “Probably the most acclaimed percussion group on Earth.” Their original compositions and arrangements include works from Reich, Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, Libby Larsen, and Tōru Takemitsu. They have collaborated with (among others) The Canadian Brass, the Kronos Quartet, and Richard Stoltzman. |

© 1986 & 1988 & 1995 Bruce Duffie

These conversations were recorded in Chicago on July 25, 1986, September 14, 1988, and December 8, 1995. Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1986, 1987, 1988, 1990, 1991, and 1996; WNUR in 2004, 2012, and 2015; and Contemporary Classical Internet Radio in 2012. This transcription was made in 2021, and posted on this website at that time.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.