|

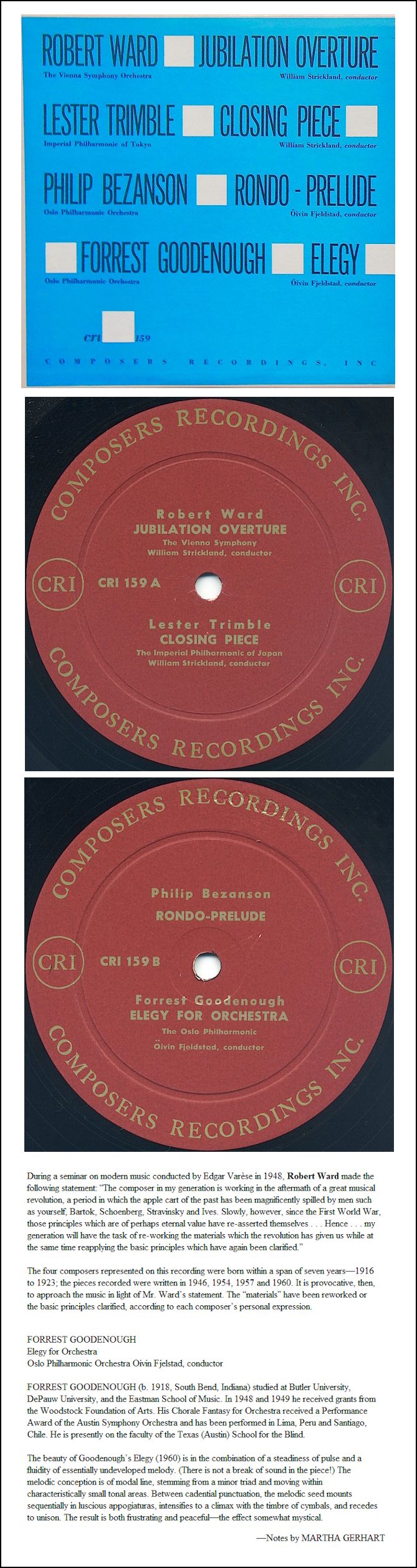

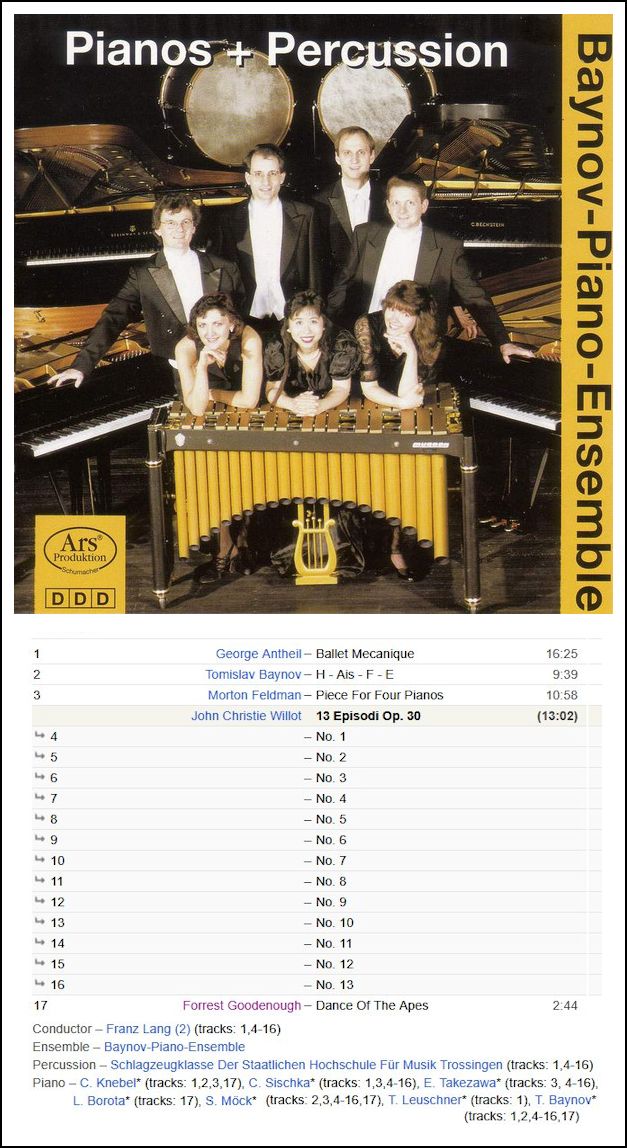

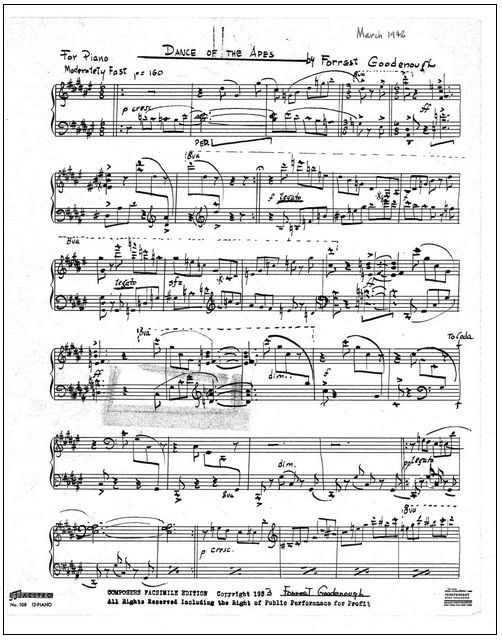

Forrest Goodenough, B.M., M.M., composer, pianist, and professor of music at Trinity University in San Antonio, was born in 1918, in South Bend, Indiana. He received national recognition in the field of composition with works performed by the New Orleans Symphony, Eastman-Rochester Symphony, Horace Britt String Quartet, the First Piano Quartet of NBC, WQXR String Quartet, and others. He was a longtime member of ACA and of the American Association of University Professors. He studied with Van Denman Thompson at De Pauw University (B.M. degree); Howard Hanson and Bernard Rogers at the Eastman School (M.M. degree); and Henry Cowell, Otto Luening, and Robert McBride at Bennington School of the Arts. The composer of the much celebrated orchestra pieces, "Chorale Fantasy" from 1950, and "Elegy" in 1960, was totally blind. He also taught at the Texas State School for the Blind in Austin. Mr. Goodenough received awards for his "Two Essays for Small Orchestra" chosen by the Albuquerque Civic Symphony, conducted by Hans Lange, had his "Symphonic Tone Poem" broadcast on CBS in 1943, and also won the Woodstock Foundation for the Arts financial support grants in 1948-49. Goodenough wrote pieces for multiple pianos, which continue to be requested, including "Dance of the Apes" and "Danza Rhythmica" which have been performed in recent years by keyboard ensembles around the world. His Woodwind Quintet was often performed on various concerts with his contemporaries, frequently including Gordon Binkerd, Roger Goeb, Otto Luening, and Richard Donovan. His "Five Piano Pieces for Children" was published by Wilking Music Company in Indianapolis. == American Composers Alliance

* * * *

*

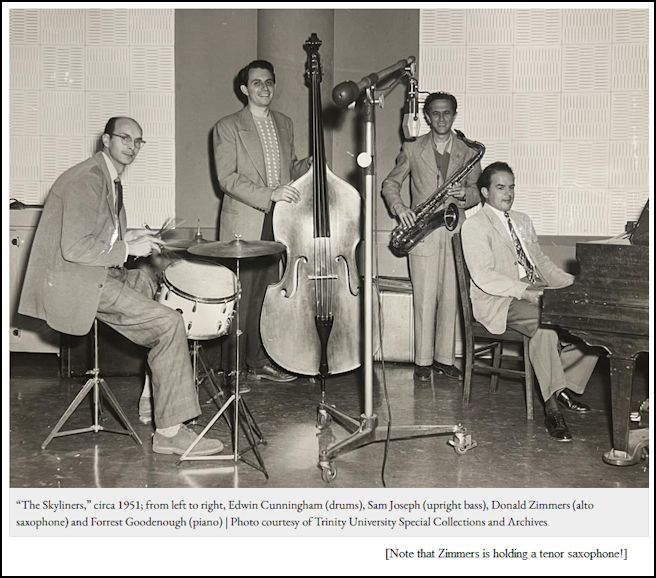

IN MEMORIAM: FORREST R. GOODENOUGH Forrest R. Goodenough was born July 27, 1918 in South Bend, Indiana, and died on August 14, 2004 in Gravette, Arkansas. He lost his sight at age five, and grew up during a time when our culture had a limited view of the amazing potential of children who didn't see. He was around people who loved him and believed he could do nearly anything -- which came to include carpentry, digging a basement under an existing house, building a cabin, ice skating, riding a tandem bicycle, cooking, finding his way around New York City, attending Butler University and DePauw University, and earning a master's at Eastman School of Music. His earliest musical compositions and performances were in grade school. In 1965 he was ranked 9th of the top 150 American composers by the American Composers Alliance. In the 1940s he lived in New York City and was the staff pianist

at NBC. He also held two other regular jazz piano jobs at the Cotillion

Room and the Barbary Room. At that time he met and ran around with George

Shearing and Lenny Tristano. In Woodstock, N.Y., he had a year-long

sabbatical to live in the Old Maverick House and complete classical In 1949 he accepted a faculty position at Trinity University in San Antonio, Tex., teaching theory and composition. In 1952 he and Dorothy Churchill Goodenough began 25 years of teaching at the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Under their guidance, the music program blossomed to include a string ensemble, an orchestra, band, and numerous award-winning soloists. He and Dorothy Churchill Goodenough were married for nearly 51 years. She died in January 2004. Forrest Goodenough passed on in Gravette, Ark., while at the Texas School for the Blind. An auditorium full of a few hundred friends, former students, and family celebrated his life and contributions. That auditorium was renamed the Goodenough Performance Hall. A charitable fund was established to benefit future students. He was survived by his daughter, Crow Johnson Evans, and her husband, Dr. Arthur F. Evans; his first wife, Lucia C. Greer; and by his niece by marriage and her husband, Diane Churchill Rautenberg and Norm Rautenberg of New Hampshire. == American Council of the Blind

|

© 1989 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded on the telephone on July 22, 1989. This transcription was made in 2026, and posted on this website at that time. My thanks to British soprano Una Barry for her help in preparing this website presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here. To read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print, as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he continued his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.