Composer / Pianist / Quiz Kid Lawson

Lunde

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Lawson

Lunde (November 22, 1935 - September 5, 2019) was born in Chicago, and made

his home in Des Plaines, Illinois (a Northwest suburb). He

began playing the piano by ear at the age of four, and later was known

to Americans as panelist “Lonny” through his eight years as a Quiz Kid.

He graduated from Maine High School, and then studied music at the

Chicago Musical College. His composition teachers were Vittorio Rieti and Robert

Delaney. He earned a degree in Psychology from Northwestern University

in 1957. In the Army, his training in psychology led to an assignment

supervising intelligence exams. Aside from his stint in the Army,

most of his career has involved music. While he played piano for a

living, composing was his main interest. Most of the music he wrote

was for the saxophone, even though he never played that instrument. Works

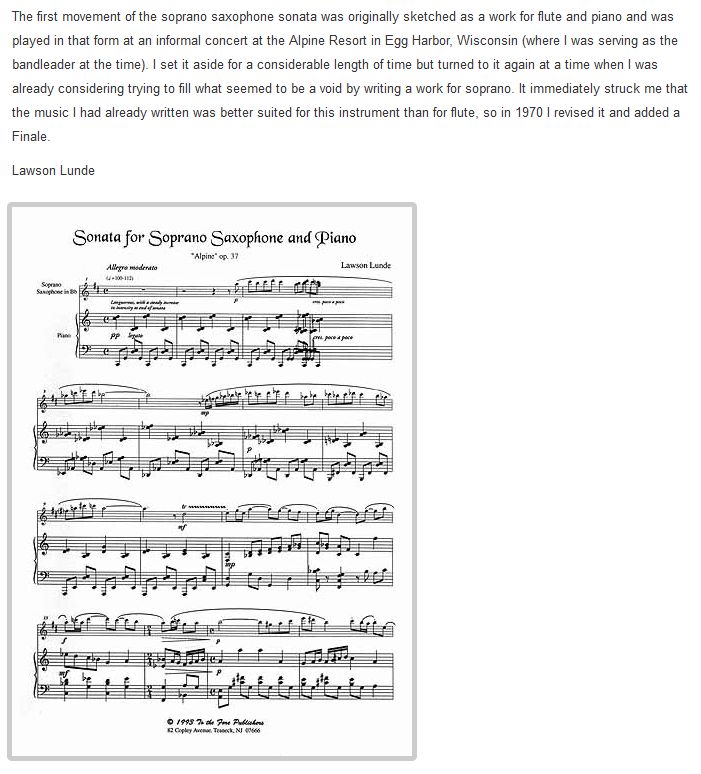

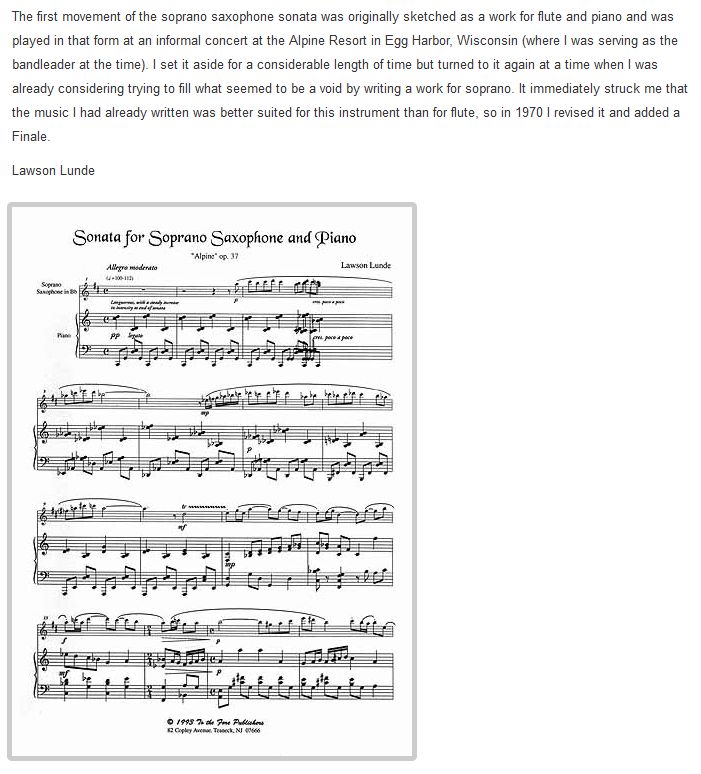

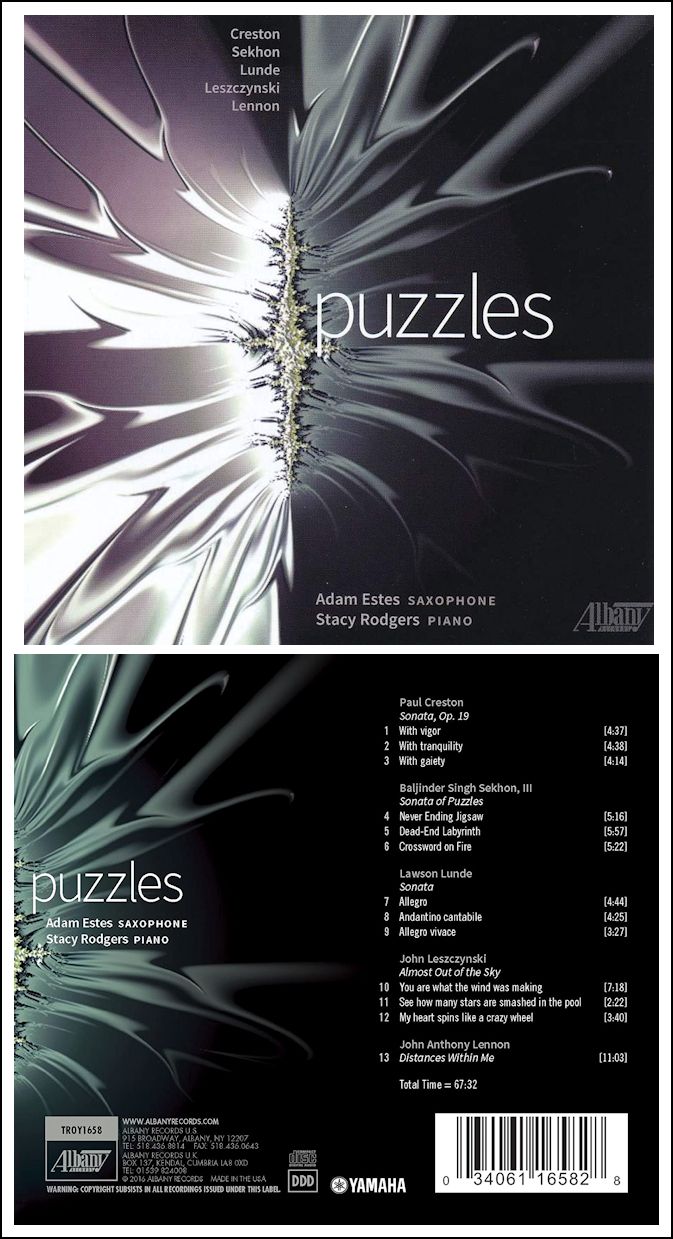

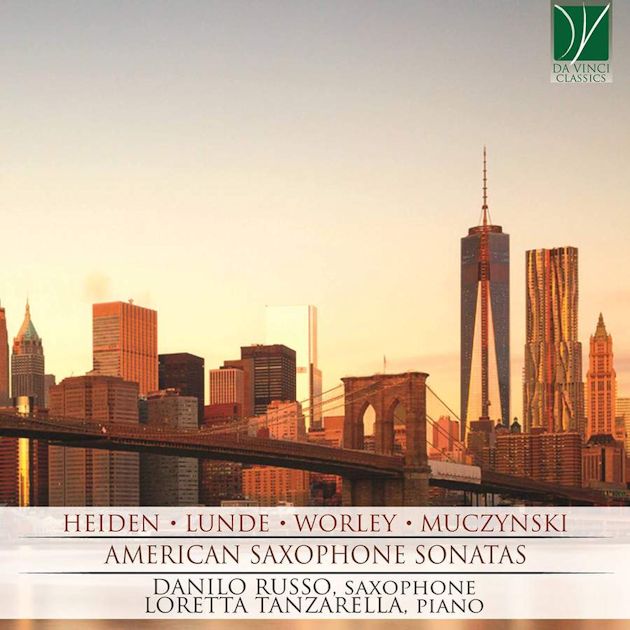

include Sonata I, and Sonata II for alto saxophone and piano,

Alpine Sonata for soprano saxophone and piano, and Suite for Saxophone

Quartet.

Lawson

Lunde (November 22, 1935 - September 5, 2019) was born in Chicago, and made

his home in Des Plaines, Illinois (a Northwest suburb). He

began playing the piano by ear at the age of four, and later was known

to Americans as panelist “Lonny” through his eight years as a Quiz Kid.

He graduated from Maine High School, and then studied music at the

Chicago Musical College. His composition teachers were Vittorio Rieti and Robert

Delaney. He earned a degree in Psychology from Northwestern University

in 1957. In the Army, his training in psychology led to an assignment

supervising intelligence exams. Aside from his stint in the Army,

most of his career has involved music. While he played piano for a

living, composing was his main interest. Most of the music he wrote

was for the saxophone, even though he never played that instrument. Works

include Sonata I, and Sonata II for alto saxophone and piano,

Alpine Sonata for soprano saxophone and piano, and Suite for Saxophone

Quartet.

This conversation

took place in February of 1987 in the studios of WNIB, Classical 97. The

station was one Lunde [pronounced LUHN-dee] had listened to quite often

during the years, and he was surprised to see what it actually looked like!

He also knew of the small menagerie of cats and dogs which inhabited

the station, and even greeted one who suddenly appeared where we were talking

. . . . .

Bruce

Duffie: You’re currently working as a pianist. How much

do you get to spend composing?

Lawson Lunde: Not a whole lot. I’m not

sure why, but it doesn’t seem to amount to very much. At the moment

I don’t have anything pressing as far as composing is concerned.

When I get started on something, I do find the time somehow.

BD: Do you get commissions for things, or

do you just write because you have to write?

Lunde: Some of each, but at the moment there

are no commissions. There is one thing on the drawing board, but

only one, and I would imagine in a couple of months or so, I’ll devote

a lot of time to it.

BD: You’re a pianist, so do you write expressively

well, or especially well for your own instrument?

Lunde: I would say it’s the hardest instrument

to write for! [Laughs] I’ve written a lot of sonatas for

solo instruments and piano, and I invariably find it harder to construct

a good piano part than otherwise.

BD: So you’re more interested in the single

melodic line?

Lunde: Right.

BD: A singing line?

Lunde: Primarily, although the trouble with

writing piano part is that I am a pianist with my own particular style

of playing. Especially since I am primarily a lounge hotel-lobby-type

of pianist, I’ve developed my own style through the years, and in some

ways it gets in the way of writing a coherent piano score.

BD: Could you reconcile what you do for a

living with what you want to do on paper?

Lunde: That’s not too easy. In some

ways they complement each other, but in some ways they run contrary.

Some of the technical figurations that I get in the habit of using

frequently in performance, are not the kind of things that would endure

themselves to the accompanists throughout the world. [Laughs]

BD: Are there any ideas that go through your

idea from your own music that you find incorporated into your cocktail

music?

Lunde: Yes. Somewhere along the line,

I would like to write some music that you might say is aimed for myself,

although I probably would be too lazy to work it up to performance pitch

myself. That would leave somebody else holding the bag, but I do

some things technically, just as a matter of course in my work, that I

really have never seen any composer put down on paper, or utilize in a

piece. It would be very effective under many circumstances, and maybe

someday I will try to write something that utilizes these things.

BD: These are things that are almost impossible

to notate?

Lunde: No, not impossible to notate, but maddingly

difficult to play. In performance, I’m heavily influenced by the

fact that I very familiar with the music of Scarlatti. I’ve played

through the complete set of sonatas many times, and some of the technical

devises he uses really fascinate me. In playing the piano, I’m finding,

and have found for years, that I am utilizing things that come straight

out of Scarlatti. For that matter I do play a lot of Scarlatti when

I’m working, but with a lot of hand-crossings and things like that.

BD: I’m surprised

that people would ask for Scarlatti.

BD: I’m surprised

that people would ask for Scarlatti.

Lunde: They seem to like it.

BD: Oh, I see... they don’t ask for it.

You just play it and they like it?

Lunde: Once in a while they ask for it, but

not as commonly as Chopin, or Joplin, or a few others.

BD: Are there some things that you get sick

of playing?

Lunde: I don’t think there’s anything you

can play endlessly and still like it. I can think of a number

of popular tunes that I used to think were very good tunes, and I really

wish nobody would ever ask me to play them again. I never play them

voluntarily, and the same goes for classical music. I don’t think

you can listen to anything constantly without... maybe not hating it, but

simply not wanting to hear it again for several years.

BD:

Have you retired some things for a while, and then come back to them?

Lunde: Yes.

BD: What about your own music? Does

it stand up as well as Scarlatti, or some of the others?

Lunde: Some of the others, yes, but Scarlatti,

no. I haven’t been very active in composing in the last few years,

and I don’t have all that good a remembrance of some of the things I

wrote in the past. When I chance to put on a tape of my music, I

know generally what’s coming next, but sometimes a particular passage will

surprise me. I don’t remember having written it precisely that way.

BD: Is that a good sign or a bad sign?

Lunde: Neutral I would say. [Both laugh]

* * *

* *

BD: You work in music all the time, and yet

your audiences are completely different. The audience for your

creative outlets is going to be different from your audience each evening.

Lunde: Completely different, yes.

BD: [With a gentle nudge] Does that

make you a little schizoid?

Lunde: Well, I suppose so. [Laughs]

I would say more so when I’m busily at work writing something.

The idea of playing one style of music for five or six hours, and then

later or the next morning working on, or trying to recapture the last

train of thought for a composition isn’t all that easy.

BD: When a composition of yours is played

on a concert, what do you expect of the audience that comes and is listening

to it?

Lunde: It depends on the circumstances.

First of all, I have not heard very many performances of my music.

It’s been played very little around Chicago. In fact, I would

guess that my music has been performed considerably more in France than

in the United States, and possibly more in Canada than the United States.

Even in the United States, generally when I hear of a performance,

it’s New York City, or North Carolina, the West coast, or something like

that. It’s seldom somewhere that I’m able to see the circumstances.

I have served as an accompanist at concerts, and I know the difference

between an audience that comes expecting to hear that kind of music,

or are there particularly to enjoy the music, contrasted with an audience

that is there to hear the prowess of the soloist. I’ve been in both

situations, and I would hope that audiences are going to enjoy my music.

I try not to be too obscure. I know my own feelings when I hear

a new piece. I very, very rarely go to a concert these days, but

I never have seen an excuse for sitting and listening to music that there’s

no way I’m going to enjoy.

BD: [Gently protesting] But how do you

know before you heard the piece if you’re going to enjoy it or not?

Lunde: Well, you don’t! There are some

active composers who are so very reliable that I virtually know I’m going

to enjoy a work of theirs that I’ve never heard, whereas I don’t think

the converse is true. I don’t think there are any that are so unreliable,

or have been so disappointing in the past that I’m certain I’m not going

to enjoy something of theirs.

BD: You’ll give it a shot?

Lunde: Yes, I’ll give it a big shot. [Both

laugh]

BD: I want to wade into the idea of greatness

in music. What do you feel contributes to making a piece of

music great?

Lunde: I’ve thought about that, and I can’t

come up with an answer. I can reel off many pieces that I consider

great, and I realize that if I were to prepare a list like that, and show

it someone else, on the list there are going to be pieces that other person

will completely agree with, and others they would wonder how in the world

I can like it.

BD: When you’re writing a piece, do you try

to instinctively write greatness into it?

Lunde: I haven’t really had occasion to

do that. I settle for trying to make it enjoyable, and that’s

about it. If it winds up with the quality of greatness, it’s not

because of anything I’ve consciously tried to put into it, and I would

imagine that’s true of virtually every composer. I can’t picture

any of the great pieces of music being great because the composers sat

down and decided, “I’m going to write a really

great one no matter what.” It just worked

out that way.

BD: Where’s the balance between the artistic

achievement and the entertainment value?

Lunde: Sometimes it’s very high. I would

say usually it’s very high, but sometimes it’s not. We all know

pieces that were not too enjoyable the first time, or even the first

three or four times you hear them, but you come to love. Even then,

the quality of greatness comes through, even though the first hearing

might not be all that enjoyable. To me, as a listener, I’m frequently

struck by the fact that maybe I didn’t enjoy this too much, but boy,

there’s something there. This is one I have to come back to, and

I’m usually right.

BD: Are there some pieces that strike

you as being really good, and then, when you hear them a couple of times

you realize it was just a passing fancy?

BD: Are there some pieces that strike

you as being really good, and then, when you hear them a couple of times

you realize it was just a passing fancy?

Lunde: Yes, I’ve found some things that I’ve

felt were very much over-rated at first hearing.

BD: Do you find as you get older

that those ideas change a little bit?

Lunde: Yes.

BD: Are you getting more tolerant, or less

tolerant?

Lunde: I would say a little bit less.

I don’t know why exactly, but I’m basically disappointed with the way

music has progressed in the last half of this century. As we’re

coming near the end of a half-century, I’m comparing things with the situation

as it was in 1950, and I think the musical scene was a whole lot better

then. I could be all wrong, and I might feel completely different

twenty years from now, but back in 1950 I was in my mid-teens, and the

music world was very exciting. People were anxiously awaiting, for

example, Shostakovich’s next symphony, and Prokofiev’s, and we wondered

if Sibelius would ever write his Eighth. Little did anyone

know that Beethoven’s Tenth would show up before Sibelius’s Eighth.

[Both laugh] Anyone who had heard William Schuman’s Third

was eagerly anticipating more, as well as more from Piston. Today,

I can’t honestly say that there’s a composer in this entire world whose

next symphony I’m eagerly awaiting, and there should be. Another

thing I’ve noticed is that this is the first era in musical history that

is divided into fifty-year segments, where it seems that even the best

composers do not improve. The best things you can sight in their output

were written early in the game. This is a switch from the past, even

from the first half of the century. You can’t picture something that

Bartók wrote in 1905 standing as the best thing he ever wrote, or

for any of the composers of the period. But nowadays, that seems

to be the case. Many of the living composers, good though they may

be, still, in all the works that stand out, the best seem to have been written

quite a while ago. In many cases, their lives have been heavily

tied up in teaching at the universities, and I personally feel that they

fall into a trap of writing music primarily to please other professors.

This, you might say, is coming full-circle back to the days of Ives

studying under Horatio Parker, which everyone still laughs at today, but

I’m not so sure we don’t have the same thing happening.

BD: Are you glad that you didn’t get into

the teaching racket?

Lunde: Yes, and no. No, because it is

the way to go as far as getting many and important performances.

But yes, I’m glad I didn’t go into it in that I don’t think I’d be very

happy with the music I would have written under the circumstances.

However, that’s just conjecture.

BD: Woulda, coulda shoulda. [Both laugh]

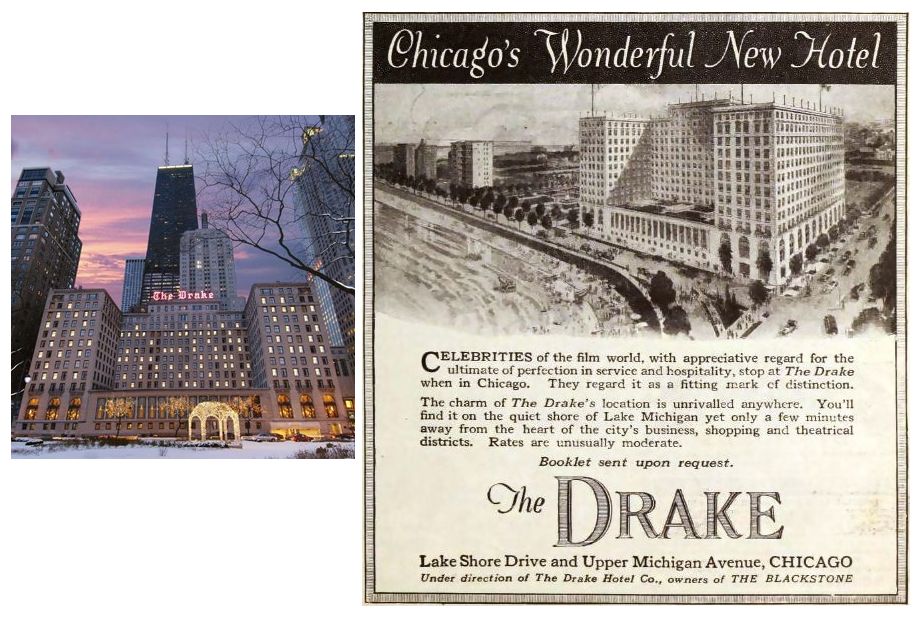

I assume that if you won the Lottery next week, you would quit your

job at the Drake Hotel?

Lunde: Yes, I would quit my job at the Drake

if I won the Lotto.

BD: And then just write, or would you do other

things besides writing?

Lunde: I’d do other things besides writing,

but I would write a lot.

BD: What kinds of other things?

Lunde: A little bit of everything.

Lunde: A little bit of everything.

BD: Before you purchase that winning ticket,

let’s talk a bit about your compositions.

Lunde: I’ve been very limited in types of

music I’ve written. I’ve written a great deal of saxophone music.

Certainly that’s what’s been most performed.

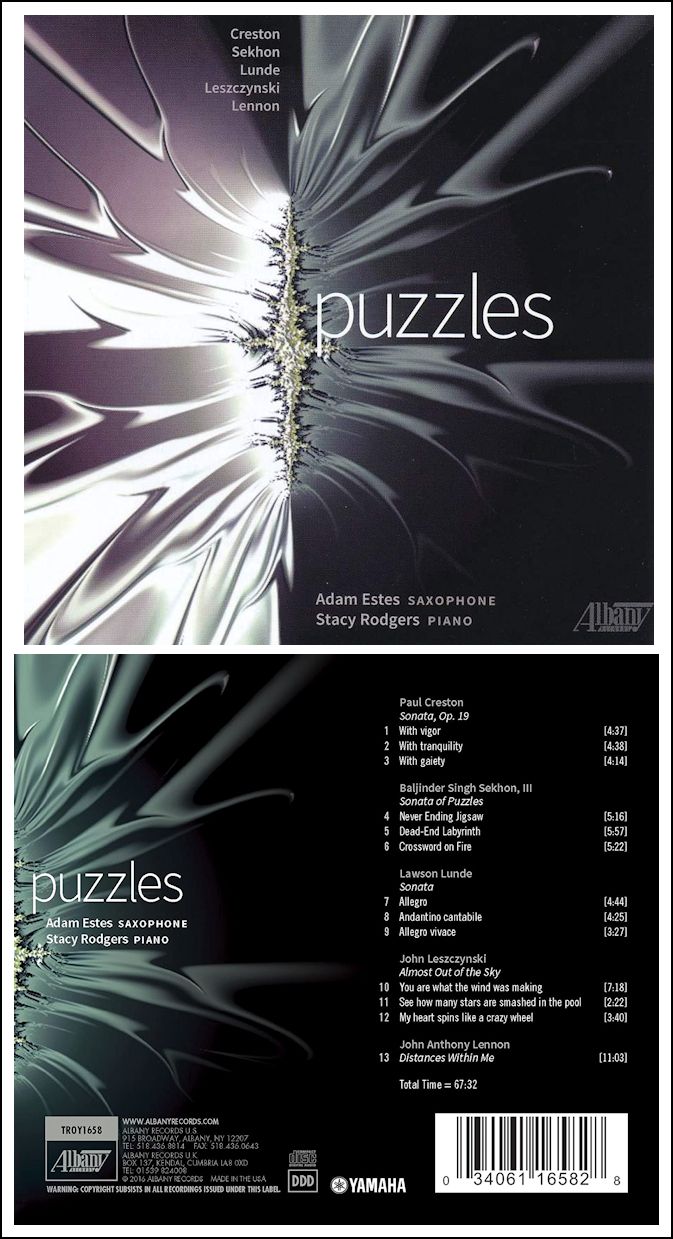

BD: Why? [Vis-à-vis the recording

shown at right, see my interviews with Vincent Persichetti,

Leon Stein, and Victor Aitay, first violinist

of the Chicago Symphony String Quartet.]

Lunde: Because through the years I’ve known

saxophonists who wanted music. It’s not the only reason, but I’ve

always liked the instrument, although I don’t play a note on it.

I like the sound of it. Unlike so many of the woodwinds, you can

write any note in the range, and they will find a way to play it.

You don’t have to worry about trills that are impossible, or leaps of

a certain interval that just can’t be done, or can only be done with great

difficulty. For a saxophone, if the notes are on the horn, a good

saxophonist will find a way to play them. I’ve also written quite

a bit of choral music, but not in large forms. The longest piece

of music I’ve ever written runs only twenty-one minutes. Somewhere

along the line — if I could spare the

time — I would like to try my hand

at something a little more substantial form-wise.

BD: A forty-minute cantata?

Lunde: Something like that, yes.

BD: Is your choral music sacred or secular?

Lunde: There is a little bit of secular, but

it is mostly sacred. I don’t think that any secular choral music

I’ve written has ever been performed.

BD: It’s sitting in the drawer?

Lunde: It’s sitting in the drawer, yes.

BD: Has it been published?

Lunde: No, not the secular stuff. With

choral music, you don’t know who’s performing it or where. You

can kind of track things like saxophone music because saxophonists are

usually going to find a way to get hold of you and ask you a question about

this or that, or at least tell you he’s playing it somewhere. But

not choral music. You see that a certain number of copies were

sold in a six-month period, and you can assume that there’s thirty copies

here and thirty-five copies there, but you seldom have any idea what’s

become of your music, you might say.

BD: Is it necessary for the composer to actually

track his music?

Lunde: No, it’s not. I have been surprised...

I was surprised on WNIB once, a few years ago! I used to do some

programs from Oberlin, and Baldwin Wallace, and I had the radio on, when

all of a sudden they were announcing a saxophone work of mine played by

a saxophonist I had never heard of. He played it very well, by the

way, even better than some of the bigger names of saxophonists who have

played the same piece.

BD: Why isn’t he a big name saxophonist?

Lunde: It was a student at the time, and for

all I know he’s got his own brokerage firm, or something nowadays. But

he played it very well, and he also came up with a very good accompanist.

It’s one of the better performances of this particular piece that I’ve

heard.

BD: Is this the same one that’s been recorded?

Lunde: Yes.

BD: You’ve had two recordings of the one piece...

Lunde: It’s at least three, plus whatever

broadcasts there have been in Europe. I know there have been some

over there.

* * *

* *

BD: When you’re writing a piece of music, are

you always in control of that pencil, or are there times when that pencil

is controlling your hand?

Lunde: Sometimes the pencil is control.

BD: Is that a good feeling?

Lunde: Yes, I would say it is.

Of course, it’s maddening if you’re suddenly being propelled along so

fast that you try to go back and fill in the blanks, and you don’t remember

exactly where your thoughts or your pencil took you. But that

doesn’t happen too often. It’s always a pleasure when twenty or

twenty-five measures suddenly write themselves all at once, especially

when you’ve been slogging along a phrase at a time, putting in a bit of

melody here, and a bit of counterpoint there, or even one measure or

half a measure at a time. It’s a pleasure to suddenly break free.

Lunde: Yes, I would say it is.

Of course, it’s maddening if you’re suddenly being propelled along so

fast that you try to go back and fill in the blanks, and you don’t remember

exactly where your thoughts or your pencil took you. But that

doesn’t happen too often. It’s always a pleasure when twenty or

twenty-five measures suddenly write themselves all at once, especially

when you’ve been slogging along a phrase at a time, putting in a bit of

melody here, and a bit of counterpoint there, or even one measure or

half a measure at a time. It’s a pleasure to suddenly break free.

BD: When you’re writing and writing, how do

you know when to put that double bar at the end? [Vis-à-vis

the recording shown at right, see my interviews with Bernhard Heiden, and Robert Muczynski]

Lunde: Oh, I don’t think that’s one of the

tougher things. That’s about the easiest thing, actually.

Basically, I’m more satisfied with my endings and my openings than what

happens in the interior of the piece. In my multi-movement pieces,

I tend to think the finale is the best movement. I don’t know if too

many composers can say that now. I personally think that Walter Piston

invariably saves his best for the last. He consistently has written

super-good finales. You can think of so many works in history that

really could have used a better last movement. It’s not worthy of

what’s gone before. I’m happy that this is true because, as Shakespeare

says, ‘all’s well that ends well’,

and that’s sometimes true. A bang-up ending can do a lot for a piece.

At any rate, I don’t have trouble putting in the double bar. I

do feel I know when to do that.

BD: When you get all the notes down, do you

go back and fiddle with the piece for a while, or do you let go right

away?

Lunde: I do fiddle... not a great deal, but

usually there are little things here and there. I don’t remove

whole sections, or substitute whole sections, or things like that.

But, as I said, I make little changes here and there.

BD: Have you been pleased with the performances

you have heard of your works over the years?

Lunde: I’ve never been very happy with what

I’ve heard from piano accompanists. I’m certain I write legibly

enough, and clearly enough so that they can follow what’s happening. It

tends to be a little too difficult for what the average saxophone player

or other instrumental player at the student level comes up with for an

accompanist.

BD: Have you ever thought of maybe writing

something that is interesting but technically easier?

Lunde: I’ve tried to scale down some piano parts,

technically, but I find it very difficult to do. Since I’ve been

playing the piano all my life, it shouldn’t be a problem to me.

There are things that I find difficult to play that some other pianists

don’t have trouble with, and other things that give me no trouble at all

which many pianists find a whole lot of trouble.

BD: What is the purpose of music in society?

Lunde: It’s a hard question to answer.

Ideally, music should be a very important part of society, a wonderful

adjunct, something that’s uplifting and entertaining at the same time.

It should also be important enough so that people want to work at

understanding it, because they realize that they’re going to get a lot

from it. As to what it actually is, at this point in time I don’t

know if anyone can give a good answer. In the past, an answer might

have been easier. The important thing of Twentieth century music

is not any person or any school of composition. It’s a phonography,

along with the radio, electronics, films, and various other things.

Somewhere along the line, somebody will be able to assess exactly what

the effect of the phonography has been. Obviously, it’s been both

good and bad. We hope it is more good than bad, but still it is a

great change from the previous century, or even the first twenty-five years

of this century. Music didn’t used to be in a situation where little

alcoves could pop up here and there, or where, if somebody wanted to be a

specialist in a certain area of music, they had to seek out certain performers.

All they had to do was to find a good record store, look at a catalogue,

and this little alcove of music would be open to them

— whether it be Lithuanian folksongs, or Javanese gamelan

music, or whatever. You can be a listening specialist in virtually

any area of music now, thanks to the phonograph. But at the same time,

the purveyors of records have immense power with what they can force on the

listening public.

BD: [It was at this point that a cat, which

had been sleeping on a shelf, woke up and pounced down, interrupting

the discussion.] I assume when you’re playing in a lobby or

a cocktail lounge, you learn to put up with just about anything.

Lunde: Anything!

BD: [Half-joking, half inquiring] Anything

at all???

Lunde: [Stoically] Anything at all!

BD: Have people thrown stuff at you?

Lunde: That never happened, I don’t think...

certainly not tomatoes or anything. Not that it might not sometime

in the future, but things are quite predictable at the Drake. Most

places I’ve played at in the past, I come to work knowing that the only

thing about the night ahead is it won’t be like the night before, and almost

anything might happen.

BD: Does it hold your interest, or is it really

boring?

Lunde: I like the unpredictability, because I

don’t want to be playing the same music every night. I like it when

I never know what musical turns an evening is going to take. Even

in a place like the Drake, it’s usually not the crowd that dictates that.

I still have the same feeling at the beginning of an evening. When

I sit down at the piano, or even launch into an introduction, I don’t know

what my first tune is going to be, much less what I’m going to be playing

in three hours hence. It’s liable to be anything. Maybe it

will depend on what the crowd wants. Maybe it’ll grab onto what flights

of fancy my own thoughts have taken me.

The Drake, a Hilton Hotel, 140 East Walton Place, Chicago, Illinois,

is a luxury, full-service hotel, located downtown on the lake side of

Michigan Avenue two blocks north of the John Hancock Center and a block

south of Oak Street Beach at the top of the Magnificent Mile. Overlooking

Lake Michigan, it was founded in 1920, designed in the Italian Renaissance

style by the firm of Marshall and Fox, and soon became one of Chicago's

landmark hotels. It has 535 bedrooms (including 74 suites), a six-room

Presidential Suite, several restaurants, two large ballrooms, the "Palm

Court" (a club-like, secluded lobby), and Club International (a members-only

club introduced in the 1940s).

|

BD: Do you try to direct it, or do you just

let it go?

Lunde: I let it go.

BD: How long do you play?

Lunde: The standard is forty minutes

on, and twenty off, but that would wind up with the end of a job being

twenty minutes off. So, you stagger it to allow for that. Plus,

if I have a lot of requests I’ll stick around until I play them all.

On the other hand, if the place has emptied out, or almost emptied out

— except for possibly four men deep in a business

conversation — then I’ll take a break

a little earlier, in anticipation of playing a longer set later.

Lunde: The standard is forty minutes

on, and twenty off, but that would wind up with the end of a job being

twenty minutes off. So, you stagger it to allow for that. Plus,

if I have a lot of requests I’ll stick around until I play them all.

On the other hand, if the place has emptied out, or almost emptied out

— except for possibly four men deep in a business

conversation — then I’ll take a break

a little earlier, in anticipation of playing a longer set later.

BD: Are there some nights that

are just no good — like Christmas

night, or special holidays?

Lunde: Definitely some nights are no good.

The night after Labor Day, and New Year’s Night are the two worst.

BD: But you still play?

Lunde: Yes.

BD: Worst, how? No enthusiasm?

Lunde: There won’t be any people.

BD: What do you do if you go into the lounge

and there is literally nobody there?

Lunde: I don’t believe it’s ever happened.

Oh, it did happen once! It wasn’t a place I was working regularly.

It was a place that I was sent to as a substitute. I got there, and

there wasn’t soul in the place except the bartender and the Maître

D’. No diners, nobody at the bar, no anything.

BD: Did you play anyway?

Lunde: In a situation like that, I probably

would play a few notes at the starting time that was established. I

was there at the appointed time but no, I didn’t.

BD: You don’t feel that by having the music

going it might draw people from the outer lobby, or from elsewhere who

were wandering around?

Lunde: If it’s a situation like that, I might.

Also, if I find that I have a very good instrument in front of me, maybe

I’ll just play for my own amusement.

BD: Would you ever write anything specifically

for that kind of crowd?

Lunde: No. I never thought of it, as

a matter of fact. I don’t think I’d know where to start.

BD: [Gently protesting] I would think

you would have so much experience in it.

Lunde: Well, tastes have changed so much,

now. Ten years ago, if you asked me something like that, I would

ask if you meant something like The Warsaw Concerto. But at

this point, two and half years have gone by without a single request for

anything like that.

BD: If you wrote something, and someone said,

“Oh, I like that! What is it?”

you could say, “It’s

one of my own pieces.

Lunde: That has happened. I’ve

written some jazz numbers that sometimes, on a dull evening, I’ll pull

out, and sometimes I get comments on them.

BD: Do you pull them out of a briefcase, or

out of your head?

Lunde: No, I don’t bring music anymore at

all. I bring music if it’s a situation where there’s a mike and

I do some singing. But various managers and club owners over the

last five or six years have been telling me they don’t want to hear my

voice anymore. It’s been quite a while since I’ve had a mike at

my disposal. I’m not the world’s greatest singer...

* * *

* *

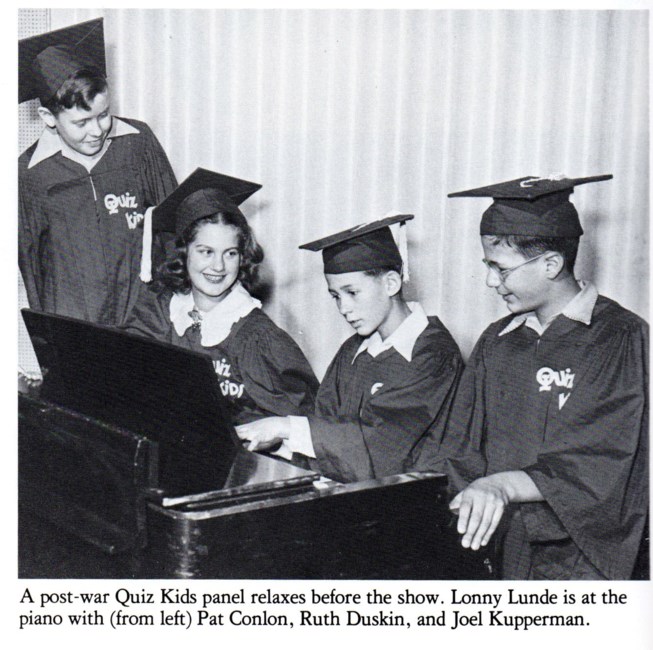

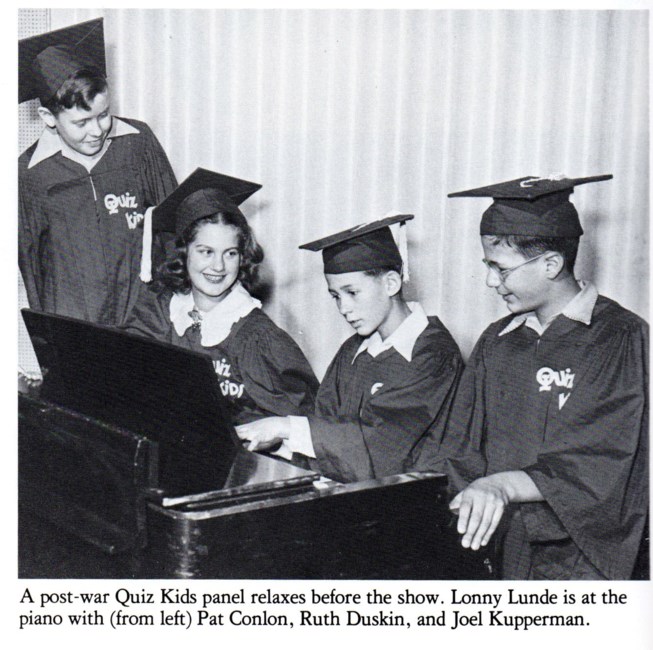

BD: Tell me about being a Quiz Kid.

Lunde: That’s ancient history! Quiz Kids

was a panel show. It was a very good radio show, but not a very

good TV show. It was only on for the first couple of years of television.

Lunde: That’s ancient history! Quiz Kids

was a panel show. It was a very good radio show, but not a very

good TV show. It was only on for the first couple of years of television.

BD: Were you radio or television, or both?

Lunde: I was in on the beginning of the television,

but primarily radio.

BD: How long were you a Quiz Kid?

Lunde: I was first on in 1944, when I was

eight. When you hit your sixteenth birthday, you were too old.

However, I didn’t make it that far because the show went off the air

when I was about fifteen and a half. I did survive till then. Primarily,

they thought I was the music expert and the sports expert.

BD: Was this local or national?

Lunde: It was national, on NBC for the most

part. Before that, it was the Blue Network, which was a predecessor

of ABC, but for the most part I was on NBC.

BD: Every week for half an hour, or an hour?

Lunde: Half hour.

BD: For thirty-nine weeks a year?

Lunde: Fifty-two!

BD: [Surprised] Really??? So you

couldn’t go out of town?

Lunde: I wasn’t on every week. It was

a competitive thing on radio. There would be five kids every week,

and the three who scored the highest, as far as answering questions,

would come back the next week to be joined by two others. If you

had done well, and stayed on the show for three or four weeks, and then

went off, you could count on being called back quite soon. Sometimes

it was two weeks later, and sometimes it was two or three months.

Basically, I was a sort of a regular.

BD: Would they give you plenty of advanced

notice, or would they call you and say that you’re on later that day?

Lunde: They’d announce at the end of the show

who the new kids the following week would be. So, if I listened

to a show that I was not on, and they gave my name, then, of course,

I would be on. I wasn’t Lawson on the program. I was Lonny

Lunde. As a pianist, I’m Lon Lunde, and as a composer, I’m Lawson

Lunde. As it happens, Lunde with the E is not too common a name.

But, if you can you believe it, another composer named Lunde has surfaced

who writes saxophone music. [This was Ivar Lunde]

BD: You were a Quiz Kid in High School. Then

did you go directly to a conservatory of music?

Lunde: When I was in grammar school through

high school, I was studying piano and composition at the Chicago Musical

College. Then I went to Northwestern, and was at their music school

for one year, but only one year. After that, I switched into a

psychology degree, psychology being much more important for a solo pianist

than a music degree. [Both laugh]

BD: Actually, it probably stood you in good

stead with the cocktail crowd. [Both laugh] Could you write

a book about the psychology of the cocktail crowd?

Lunde: No, I’d be afraid of getting sued.

BD: Then why did you get out of music?

Lunde: I’m not sure... The faculty at

the time was a big disappointment to me. However, as soon as I

got out, they had a wholesale house cleaning in the school of music, and

some of what I considered deadwood was replaced by some very good people.

A couple of years later, I thought a great deal more of the school

of music than I had when I’d been a student in it.

BD: By why psychology? Why not business

or engineering?

Lunde: I don’t know. It wasn’t a conscious

switch to psychology. It was the conscious switch to liberal arts.

I got a major in psychology, but that wasn’t clear until near the end

of my third year. It could have been any one of several things.

First of all, I had no idea that I’d be going into music.

I was planning to go to law school, and I did go to law school for one

year. There’s a feeling which I had, and which many other people

also felt — fraternity brothers of

mine — that when you’re in a school

like music, or engineering, or speech, as your college days go on, you

get the growing feeling that you’re not being educated. You start

to envy these people who are talking so fluently about political science,

and economics, and history, and the social sciences, and you think you’re

missing out. In business school, people fell down more than any others.

They were being trained to do something, and they felt that an education

was right at their fingertips, but it was passing them by. I felt

that at music school. I was enjoying my liberal arts electives more

than learning from some professor what sonata form was... as if I needed

to know. [Both laugh]

BD: If you’re going to compose, you should

know what a sonata is, shouldn’t you?

Lunde: Oh, sure, but I don’t think you have

to wait to go to college to learn about form in music.

BD: What advice do you have for someone who

wants to go to college for music? Stay away from it?

Lunde: Oh, no! I don’t think so.

Choose a school carefully. That’s about it. I’m so removed

from the college scene at this point that I don’t have any specific advice.

I get the impression that musical education being offered nowadays is

much more comprehensive that it was in my day, and there are many more

avenues you can follow.

BD: What advice do you have for someone who

just wants to be a composer?

Lunde: [Thinks a moment] Go and follow it.

Compose several things in different styles and different forms. At a certain

point, take a look at them and see what you have. Evaluate what

you do best, and then show the works to others to see what they think you

do the best. That would primarily be my advice.

Lunde: [Thinks a moment] Go and follow it.

Compose several things in different styles and different forms. At a certain

point, take a look at them and see what you have. Evaluate what

you do best, and then show the works to others to see what they think you

do the best. That would primarily be my advice.

BD: Do you have you any advice for someone who

wants to be a concert pianist?

Lunde: [Thinks again] My first advice

is stay away from the competitions. There are other avenues to

being a concert pianist, and that is the roughest of all. It is so

rough, that I’m surprised anybody goes in for the idea of trying to becoming

a concert pianist via winning competitions. Obviously, it happens.

Some of the most renowned pianists did enter the concert scene that way,

but there are other avenues that would be much better... Commission an excellent

composer to write a piano concerto for you. A fine piano concerto

by a fine composer will get played, and if you have the rights to the performance,

you will be the pianist. And if you’re good, that will be your

entry to the concert scene.

BD: What if somebody wants to be a cocktail

pianist?

Lunde: Get a lot of experience with bands.

Those who have had band experience do a lot better than those who haven’t.

They just play better. They know more music. and they’re less

set in their ways. The more different kinds of bands you can play

with greatly enhances your ability to be a one-man show.

BD: Do you have any advice for audiences of

new music?

Lunde: Enjoy! Don’t concentrate on the

listening so hard that it becomes drudgery, but give everything a good

chance. That’s about all. If a concert is such that most of

the audiences is there to hear the musician(s) rather than the music,

I hope that those people would reconsider. To my way of thinking,

the music is always more important than the performance. I’d much

rather hear a worthwhile piece of music I’ve never heard before

— even if it’s not played especially well

— than a not-very-good piece played brilliantly.

BD: There must be some pieces that you want to

come back to often.

Lunde: Oh, sure. As far a new music

is concerned, I can certainly name you some composers I invariably seem

to very much enjoy, and get the feeling that I want to hear as much of their

output as possible, and rehear the works I do know. Among them are

George Rochberg, Robert Ward, and Norman Dello Joio.

Those would be ones that definitely stand out for me. Then there’s

a very wide spectrum of composers that the jury is still out as far as

I’m concerned, but have written things that have really registered with

me. Then there are a few — fortunately,

not too many — that whoever their

music is for, I don’t think it’s for me. Although even there, let

me hear just one work of theirs that really registers, and I will go scurrying

back to some of their things that I’ve dismissed in the past.

BD: The one piece would give you the key to

other pieces?

Lunde: I’d want to see if it did. I

can’t give you a specific instance of when that’s happened, although

it strikes me that somewhere along the line it has.

BD: You say you’re not really convinced where

music is going?

Lunde: I don’t think anyone is. I certainly

think minimalism will be a thing of the past in twenty years. In

its own way, it’s like the top forty charts of today. There is a

sort of primitivism, that it’s telling the audience, “Look

how dumb you are.” That’s my opinion, of

course. Some people take minimalism really seriously, and certainly

it’s possible to write good music in that form. But it’s a whole

lot easier to write bad music, and I can’t see it being any lasting value.

On the other hand, I think that twelve-tone music has pretty well turned

belly-up, even though it lasted for many decades. I know one professor

who told his composition students they could only get an A if they wrote

twelve-tone music.

BD: That sounds like a straightjacket.

Lunde: It is kind of staggering, actually.

As a good example, Rochberg’s Concord Quartets would be awarded a

grade of B. This is not to say that there might not be room for another

twelve-tone masterpiece here and there. But still, it’s pretty

well proven that ultimately, one work is too much like another, and there’s

only room for so many. Its value is not primarily to entertain,

but to be theoretical and doctrinaire. When I listen to Schoenberg,

for example — which isn’t often

— it’s usually Pierrot Lunaire. I

happen to like it very much, but somehow I never find myself wanting to

hear Erwartung, or Ode to Napoleon, or any of his other atonal

vocal music. As far as I’m concerned, for my enjoyment, Schoenberg’s

vocal music begins and ends with Pierrot Lunaire. This is what

the history of twelve-tone music has turned out to be. It’s easy

for an opera lover to find room for Wozzeck and Lulu, but

the other atonal operas that have been written through the years, and they’re

not going to get listened to, even by twelve-tone music enthusiasts.

BD: Do you expect your music to last?

Lunde: [Sighs] It’s hard to tell.

If it does, I would think it would be through writing in areas where

the instrumentalists need music, which has been the case with the saxophone.

Even today, there’s a lot more saxophone music being written than twenty

or thirty years ago. Still, it’s not an area that has been loaded

with good things to play, when you compare it to the choice a violinist,

or a pianist has. I like to write music that I feel there’s a need

for. If I should hit another flurry of composition, it might very well

be for instruments that I think are under-represented.

BD: Such as the double bass?

Lunde: Yes! That’s would certainly be

one of them. Also, the viola is underrepresented, actually.

Seemingly there’s been a flurry of trombone music lately. I notice

that Zwilich’s Trombone

Concerto is going to be played by the Chicago Symphony. Seemingly,

in the last few months I’ve turned up a good deal of fine trombone music

that I didn’t know existed.

BD: The Orchestra of Illinois played the Erb Concerto.

Lunde: Yes, and your station played a work by Gunnar

de Frumerie (1908-1987). I think it’s an absolute masterpiece.

He would be an example of a composer that was unknown to me, but I’m now

familiar with four of his pieces. I give two of them top rating.

It’s a crime that audiences in this country don’t get a shot at

hearing this kind of music. As far as I’m concerned, audiences would

probably love that trombone work of Frumerie. [The Cello Concerto

(1984) has an interesting history. It was adapted from his Second

Cello Sonata. He then adapted it into a Trombone Concerto,

and was his last completed work. It was specifically written for

the Swedish trombone virtuoso Christian Lindberg.]

BD: One last question. Is composing fun?

Lunde: I think so. It’s work and fun.

It’s rewarding. I don’t know if I’d say the same thing if I was

writing film music, and was under a severe deadline to write a certain

bit of music that’s exactly forty-seven and half seconds. I have a

feeling that I wouldn’t think it’s fun at all under those circumstances.

But in a way it’s quite relaxing.

BD: That is the first time I’ve ever heard

it described as relaxing.

Lunde: It is, in a strange sort of way.

But, as I said, it would be predicated on the idea that you’re not under

extreme time-pressure.

BD: You can really call your own shots for the most

part?

Lunde: Yes. On occasion, I have gotten

started late in the evening on a choral thing, and it made the writing

is so enjoyable that I have it virtually finished before the night is

over and the sun rises. At least I have it finished except for some

minor details.

BD: I’m glad we finally got together.

Lunde: I am, too.

========

========

========

---- ---- ----

======== ========

========

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This conversation was recorded in Chicago on February 3, 1987.

Portions were broadcast on WNIB in 1990. This transcription was

made in 2020, and posted on this website at that

time. My thanks to British

soprano Una

Barry for her help in preparing this website

presentation.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed

and posted

on this website, click here. To

read my thoughts on editing these interviews for print,

as well as a few other interesting observations, click here.

* * * *

*

Award -

winning

broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical

97 in Chicago from 1975

until its final moment as a classical

station in February of 2001. His interviews

have also appeared in various magazines and journals

since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series

on WNUR-FM,

as well as on Contemporary

Classical Internet Radio.

You

are invited to visit his website for more information

about his work, including selected

transcripts of other interviews, plus

a full list

of his guests. He would also like to call your

attention to the photos and information about

his grandfather,

who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago.

You may also send him E-Mail with comments,

questions and suggestions.

Lawson

Lunde (November 22, 1935 - September 5, 2019) was born in Chicago, and made

his home in Des Plaines, Illinois (a Northwest suburb). He

began playing the piano by ear at the age of four, and later was known

to Americans as panelist “Lonny” through his eight years as a Quiz Kid.

He graduated from Maine High School, and then studied music at the

Chicago Musical College. His composition teachers were Vittorio Rieti and Robert

Delaney. He earned a degree in Psychology from Northwestern University

in 1957. In the Army, his training in psychology led to an assignment

supervising intelligence exams. Aside from his stint in the Army,

most of his career has involved music. While he played piano for a

living, composing was his main interest. Most of the music he wrote

was for the saxophone, even though he never played that instrument. Works

include Sonata I, and Sonata II for alto saxophone and piano,

Alpine Sonata for soprano saxophone and piano, and Suite for Saxophone

Quartet.

Lawson

Lunde (November 22, 1935 - September 5, 2019) was born in Chicago, and made

his home in Des Plaines, Illinois (a Northwest suburb). He

began playing the piano by ear at the age of four, and later was known

to Americans as panelist “Lonny” through his eight years as a Quiz Kid.

He graduated from Maine High School, and then studied music at the

Chicago Musical College. His composition teachers were Vittorio Rieti and Robert

Delaney. He earned a degree in Psychology from Northwestern University

in 1957. In the Army, his training in psychology led to an assignment

supervising intelligence exams. Aside from his stint in the Army,

most of his career has involved music. While he played piano for a

living, composing was his main interest. Most of the music he wrote

was for the saxophone, even though he never played that instrument. Works

include Sonata I, and Sonata II for alto saxophone and piano,

Alpine Sonata for soprano saxophone and piano, and Suite for Saxophone

Quartet. BD: I’m surprised

that people would ask for Scarlatti.

BD: I’m surprised

that people would ask for Scarlatti. BD: Are there some pieces that strike

you as being really good, and then, when you hear them a couple of times

you realize it was just a passing fancy?

BD: Are there some pieces that strike

you as being really good, and then, when you hear them a couple of times

you realize it was just a passing fancy? Lunde: A little bit of everything.

Lunde: A little bit of everything. Lunde: Yes, I would say it is.

Of course, it’s maddening if you’re suddenly being propelled along so

fast that you try to go back and fill in the blanks, and you don’t remember

exactly where your thoughts or your pencil took you. But that

doesn’t happen too often. It’s always a pleasure when twenty or

twenty-five measures suddenly write themselves all at once, especially

when you’ve been slogging along a phrase at a time, putting in a bit of

melody here, and a bit of counterpoint there, or even one measure or

half a measure at a time. It’s a pleasure to suddenly break free.

Lunde: Yes, I would say it is.

Of course, it’s maddening if you’re suddenly being propelled along so

fast that you try to go back and fill in the blanks, and you don’t remember

exactly where your thoughts or your pencil took you. But that

doesn’t happen too often. It’s always a pleasure when twenty or

twenty-five measures suddenly write themselves all at once, especially

when you’ve been slogging along a phrase at a time, putting in a bit of

melody here, and a bit of counterpoint there, or even one measure or

half a measure at a time. It’s a pleasure to suddenly break free.

Lunde: The standard is forty minutes

on, and twenty off, but that would wind up with the end of a job being

twenty minutes off. So, you stagger it to allow for that. Plus,

if I have a lot of requests I’ll stick around until I play them all.

On the other hand, if the place has emptied out, or almost emptied out

— except for possibly four men deep in a business

conversation — then I’ll take a break

a little earlier, in anticipation of playing a longer set later.

Lunde: The standard is forty minutes

on, and twenty off, but that would wind up with the end of a job being

twenty minutes off. So, you stagger it to allow for that. Plus,

if I have a lot of requests I’ll stick around until I play them all.

On the other hand, if the place has emptied out, or almost emptied out

— except for possibly four men deep in a business

conversation — then I’ll take a break

a little earlier, in anticipation of playing a longer set later. Lunde: That’s ancient history! Quiz Kids

was a panel show. It was a very good radio show, but not a very

good TV show. It was only on for the first couple of years of television.

Lunde: That’s ancient history! Quiz Kids

was a panel show. It was a very good radio show, but not a very

good TV show. It was only on for the first couple of years of television. Lunde: [Thinks a moment] Go and follow it.

Compose several things in different styles and different forms. At a certain

point, take a look at them and see what you have. Evaluate what

you do best, and then show the works to others to see what they think you

do the best. That would primarily be my advice.

Lunde: [Thinks a moment] Go and follow it.

Compose several things in different styles and different forms. At a certain

point, take a look at them and see what you have. Evaluate what

you do best, and then show the works to others to see what they think you

do the best. That would primarily be my advice.